We create the Universe: artists and scientists take on the Big Bang

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108

Abstract

Between October 2021 and January 2022 an ambitious combined art and science exhibition presented a unique object-rich cosmological story at the University Library of Leuven, Belgium, as part of the Kunst Leuven KNAL! City Festival 2021 (English: BANG! Big Bang City Festival). To the Edge of Time was a transdisciplinary[1] introduction for general audiences to one of the most famous and complex developments in science, the Big Bang theory. The exhibition presented artworks and science objects as equal partners that through curatorial placement and interpretation could fluidly convey key theoretical moments, materials, philosophical perspectives and ideas.

The scientific story focused on how the groundbreaking work of the Belgian priest-astronomer Georges Lemaître bridged the insights of two of the twentieth century’s other leading European scientists, German physicist Albert Einstein and the British cosmologist Stephen Hawking. Objects from their lives and archives revealed their specific ideas and processes of thinking and discovery. Artworks from leading international artists brought new material, critical and conceptual dimensions and multisensory encounters.

The exhibition was the result of a curatorial collaboration between the author, British contemporary art and transdisciplinary curator Hannah Redler-Hawes, and Belgian cosmologist and former collaborator of Stephen Hawking, Professor Thomas Hertog, of KU Leuven. As guest curators, they worked with Annelies Vogels, Exhibition Coordinator of the university and Wouter Daenen of KU Leuven Libraries, and others to form a closely collaborating curatorial team. To the Edge of Time was not only the first exhibition worldwide to explore Lemaître’s work through a transdisciplinary narrative, but also to place Stephen Hawking’s work in a broader historical context. In the trans- and interdisciplinary exhibition field, where new commissions and collaborations between living artists and scientists have been increasing, it was somewhat unusual for a cosmology exhibition in its reliance on material culture, concentration on historical art and science objects and its combining of these with presentations of recent contemporary art and advanced theoretical physics concepts. These combinations helped to convey parallel movements of thought where neither the art nor the science were presented as derivative to each other, a key curatorial ambition.

This practice-based paper, offering Redler-Hawes’s personal reflections, discusses how the narrative evolved to define a shared language between the contributors. It considers, through a narrated walk-through of key object-artwork ‘constellations’, how the presentation generated new insights into different methods of enquiry, knowledge acquisition and making sense of our place in the cosmos, by bringing major themes in twentieth century science into dialogue with international artists working independently and in collaboration with science during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.[2]

Note: Where images belong to the Science Museum Group this Journal shares them under a fully open access CC-BY licence (see our Open Access statement here https://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/about-the-journal/). Where the image or work belong to a third party, this is indicated in the credit in the caption and full rights belong to the indicated party.

Keywords

Albert Einstein, contemporary art, cosmology, Curating, exhibitions, experiment, Georges Lemaître, interdisciplinary, multi-disciplinary, space, Stephen Hawking, Time, transdisciplinary

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Did the Universe have a beginning? Will it come to an end? Where do humans fit into the big picture? Scientists and artists have considered these immense questions and have come up with some truly amazing ideas.

To the Edge of Time exhibition text, October 2021[3]

Between October 2021 and January 2022 an ambitious combined art and science exhibition presented a unique object-rich cosmological story at the University Library of Leuven, Belgium, as part of the Kunst Leuven triennial city festival KNAL! (English: BANG! Big Bang City Festival)[4]. To the Edge of Time was intended as a transdisciplinary[5] introduction to ‘the gradual disclosure of the Big Bang hypothesis (1915–1965)’[6], and the 1931 vision of the Universe originating in a primeval atom by the Belgian priest-astronomer and Leuven professor, Georges Lemaître. The transdisciplinary approach followed the festival ambition outlined by Emeritus Professor Marc Vervenne, theologian and member of the KNAL! organising committee, to ‘consider through mythology, religion, art, literature, the contemporary and early sciences our abiding wonder and ongoing quest for insights into the origin of the Universe and our place as humans in that immeasurable system’.[7] With its sister exhibition Imagining the Universe[8], To The Edge of Time would be the flagship offer of the festival.

As a contemporary art curator specialising in inter- and transdisciplinary exhibition-making, I was approached by Kunst Leuven to curate the exhibition. I was to work with a KU Leuven professor, the cosmologist Thomas Hertog[9], initially identified as the ‘scientific adviser’, to translate and evolve his concept for a science story into an audience-focused art and science narrative in collaboration with Annelies Vogels and the exhibition team at KU Leuven Library.

Hertog’s proposed story advocated against presenting Lemaître in isolation, arguing we should rather demonstrate how Lemaître’s groundbreaking work bridged the major theoretical insights of two of the twentieth century’s most famous European scientists, Albert Einstein and Hertog’s long-time collaborator Stephen Hawking.

Placing Lemaître between two colleagues with rockstar status created an otherwise unlikely crowd-pulling recognition factor; Lemaître is not widely known outside cosmological circles, or even these days so frequently cited within them. (Although ‘the riddle of cosmic design drove much of Hawking’s research’, Hertog had to program Lemaître’s name into Hawking’s voice synthesizer in 2011.)[10] Featuring Hawking grounded the concept in Hertog’s current KU Leuven academic work, which builds on their collaborations. Looping Lemaître’s central work back in time to its origin in Einstein’s great insights, and forwards, via its significance to Hawking and Hertog, meant that Leuven’s most famous scientist could be presented as a figure of as much importance to the future of cosmology as to its past.[11]

The opportunity to work with a living witness who could bring unique insights into this story was exciting, and we quickly realised that working as co-curators would allow us to shape a more entangled context. Key curatorial questions were: How could we bring the Big Bang story to life through a stimulating, multisensory and appealing art and science exhibition? What would the selection criteria need to be for artworks that could enter into dialogue with significant historical science artefacts? How would we position those artworks within a science story that was unique to KU Leuven, whilst retaining – or expanding – their conceptual integrity?[12] And how might our joint interpretations allow visitors to experience artistic and scientific investigations into the Universe as two distinct but frequently entangled or corresponding fields of research?

Bringing the Big Bang story to life

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108We developed a story arc which spanned the development and influence of Lemaître’s Big Bang theory from 1900 to the present day. Perhaps ironically for an exhibition questioning the existence of time, we decided to present the scientific narrative and objects chronologically, providing the Big Bang story with a beginning, middle and future (not ‘end’). This allowed people new to the story to build relationships between the key ideas.

We began with the startling moment when Einstein’s 1915 theory of gravity overthrew centuries of Newtonian beliefs to unlock new ways of thinking about the cosmos. After presenting Lemaître’s bold ideas, we concluded with the latest insights and extensions of the Big Bang theory by Stephen Hawking and his contemporaries in the early twenty-first century. Visitors could trace the radical scientific ideas at the turn of the twentieth century, now essentially accepted as fact, to the more speculative twenty-first century hypotheses, which still feel, arguably, closer to science fiction. Conversational area panel texts rooted the scientific developments in six key moments, moving from Einstein’s remodelling of space and time to the ‘edge’ of time conceptualisation which Hertog advocates for. Object and artwork labels connected each exhibit to the story, provided important context, and articulated artists’ intentions and how their work spoke to or riffed off the story.

A number of historically significant, or ‘epistemic objects’[13] (Tybjerg, 2017; Pickstone, 2000) anchored the science story: glass positive of Arthur Eddington’s photograph of the total solar eclipse at Sobral – which supplied evidence supporting Einstein’s theory of gravity over Newton’s; Lemaître’s extraordinary 1927 first sketches of the expanding Universe, a blackboard which had hung in Stephen Hawking’s office from the 1980s until his death (see Juan-Andres Leon in this issue for a detailed discussion of Hawking’s blackboard); and a drawn depiction by the visionary 1970s physicist John Wheeler of the Universe as a U-shaped object, with an eye on one side gazing at its own past (discussed in more detail later in this article). Parallel and responsive artworks, some of which spoke more eloquently to key scientific themes or concepts than any objects we could find, and themselves the result of sustained artistic research, offered far-reaching unexpected connections and multisensory trajectories.

Building the art narrative

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108All my work – or most – is to do with the connection between humans, nature and the cosmos. Light is the absolute principle. Not lighting. My interest is in the photon, the actual energy.[14]

Liliane Lijn

In proposing what art might resonate with the story and Hertog’s wish-list of science objects, I mapped the science story for materials, phenomena, ideas or approaches against artistic practice from across the globe. I researched artists who materially or conceptually explore the physical phenomena of cosmology, the limits of matter, imagination and our slippery relationship with reality, as well as the significant role imaging technologies have on our image and understanding of the Universe. Many of the artists I researched collaborate closely with theoretical and experimental physicists in their work, others respond to ancient or modern science, while others still create or created their work in entirely different ‘frames’, including literature, science fiction, mythology, magic, ritual, psychoanalysis, post-colonial theory and radical socialism. The artists’ enthusiastic embrace of the opportunity for their work to be experienced in this context allowed us to broaden the dimensions of our enquiry.

Works that could speak to the underlying thesis that contemporary cosmology invites a new and radical understanding of time were appealing, as were works using light as a sculptural material (including Liliane Lijn’s ‘Liquid Reflections’, 1966–1968, and Troika’s ‘Borrowed Light’, 2018), as a means of revelation and enclosure, or as a method to create abstract patterns in raw data connecting us the early stages of matter (Semiconductor’s ‘HALO 0.3, 0.1’, 2018). Many artists I looked at adopt particular or unconventional methods, enacting fanciful or irrational processes that might employ observation or measurement but can’t be described in scientific terms. Other artists question the processes of cosmology, or the construction and contingency of meaning (Dawit L Petros), and how processes of knowledge acquisition are neither benign nor historically inclusive (such as Jackie Karuti’s ‘The Planets – Chapter 32’, 2017). I researched those who addressed the expansive or reductive potential of science, the more abstracted and philosophical implications of the narrative and the riddle of existence through an engagement with the metaphysical or spiritual dimensions of considering our place in the cosmos (see ‘Approaching abstraction’ below).

Conceptually, the idea that Lemaître’s work was built on a discrepancy in the world’s most famous scientist’s thinking, and that we should present his work through his relationships with other researchers, was compelling. Hertog’s positioning of Lemaître between Einstein and Hawking reinforced the essential role of collective work and resisted the notion of solitary scientific genius.[15] It created a curatorial opportunity to highlight science as a social, provisional, often fallible and collaborative process, creating a porosity in which there was space for a wide range of artistic approaches.

Having established that there was neither the resource nor the time-frame to populate the entire exhibition with commissions, I identified two main areas of practice for our art selection criteria to focus on: ‘responsive’ research: artworks created in any year or place between 1900 and 2021, in response to any aspects of the science story; and parallel practice: artistic thinking that we could argue contributed to a zeitgeist that fostered as well as responded to new developments in science.

It felt important to represent the equal significance of new artistic thinking as well as symbiosis between the fields[16], and this led us to some serendipitous, most likely coincidental, conceptual and formal connections (discussed further in the ‘Constellations’ section below).

I did not restrict the research to any particular movements, regions or artistic schools of thought, and I tried to avoid shallow or illustrative interpretations of either the science or the artworks – an approach which could only lead to a weak or misleading story, or refusal from artists approached to get involved.

Hertog and I spent many hours on video calls together and with Annelies Vogels and Lien De Keukelaere, the festival director, debating our final selection against science objects selected for their connection to the key ideas and key moments in each of Einstein, Lemaître or Hawking’s professional life. Our final science and art strands wove in and out of each other, sometimes building on intimate connections for audiences to consider, at others creating pathways to larger related themes or questions.

Constellations: science and art in 'To the Edge of Time'

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108Rugoff (2006) offers a definition of a ‘great group exhibition’ as one which ‘…asks its audience to make connections (…) brings things together in stimulating and unpredictable combinations. (…) immerses us in an experience of shifting yet interlinked viewpoints’ and ‘juxtaposes works whose overlapping concerns resonate in ways that transform our experience of them’.

The following sections offer a descriptive walk through some of the connections and arrangements, or ‘constellations’ we aimed to forge between exhibits. They do not need to be read sequentially although they do follow the sequence of the exhibition.

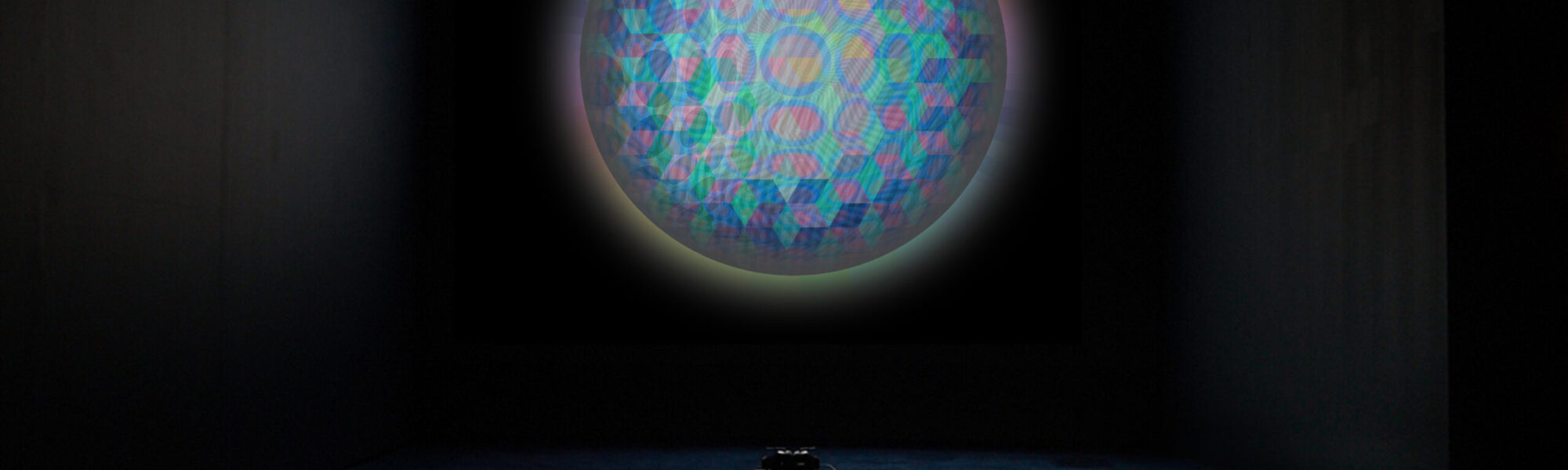

To the Edge of Time was the first major exhibition at the Library to include either science objects or contemporary art. A series of ‘attractor’ artworks between the Library and main gallery entrance set the scene for an exhibition where expectations about time, space, observation and perspective would be disrupted and explored: Haseeb Ahmed’s ‘The Cosmologist’s Desk’ (2021) sat at the main entrance, with household objects ‘performing’ behaviours designed to ‘reveal’ the usually imperceptible gravitational waves that our world withstands; Mark Wallinger’s moving image ‘Orrery’ (2016) directly outside the iconic Library reading room positioned us rather than the Sun at the centre of a Universe in motion; and the glittering mirror ball of Katie Paterson’s ‘Totality’ (2016) projected dazzling images of nearly every solar eclipse documented by humankind across the entire entrance threshold, transporting visitors into cosmic space.

Belgian design studio Exponanza’s work also supported the transformation of galleries created for intimate book displays into a series of seductive, other-worldly narrative spaces. They used the metaphor of an evolving grid which followed developments in scientific ideas about spacetime in the story, exhibits, interpretation and bespoke gallery furniture. Throughout the spaces, 2D design and 3D forms emerged along a rectangular Euclidean pattern through static, dynamic and ‘no boundaried’ space, before finally appearing to move beyond geometry.

The grid, which can also be considered as a frame derived from scientific and theoretical models that make no difference between art and science. We took the position that art, science and religion arise from an idea, which then takes shape in a first note or pencil stroke on paper. The grid connected the ideas, theories and artworks through dots, lines and planes. In the exhibition it created a mesh within which everything could take shape and upon which everything could come together.[17]

Ward Denys

Bold new worlds

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108In the exhibition’s first half we sought to create a culture of innovative, bold new thinking. Story hooks centred on the spectacular break from tradition that Einstein’s work brought and the audacious courage of Lemaître in his challenge to the world’s most famous scientist (see section <i>t=0</i>… below).

Gallery 1, Einstein remodels time and space, brought together Eddington’s eclipse image, news items which cemented Einstein’s theories in the popular imagination, and artworks chosen to create a sense of ideas about time and space being in constant flux.

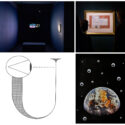

Our first ‘serendipitous connection’ with art contemporaneous to developments in science came in the form of a rare Suprematist[18] drawing, ‘Suprematist Composition (Mixed Feelings)’ (1916) by Ukrainian/Russian painter Kazimir Malevich.[19] In 1915, the same year Einstein published his theory of gravity, Malevich established Suprematism with ‘Black Square’, the painting many consider the ‘Hour Zero of Modern art’.[20] It was thrilling to imagine encountering Suprematism’s never-before seen (in Western art) perspectives looking down from gravity-less space[21] in a world rocked by Einstein’s groundbreaking thinking.

Malevich’s drawing brought a powerfully destabilising sense of movement to a room against other dynamic works including Lilian Lijn’s 1968 quantum-inspired kinetic sculpture, ‘Liquid Reflections’ and Cornelia Parker’s ‘Einstein’s Abstracts’ (1999). We interpreted Leo Robinson’s 2017 pencil drawing and collage ‘The Lake (Newton)’ as capturing the profound moment when Einstein replaces Newton’s mystical conception of the Universe, marking the birth of modern cosmology. We also placed Gavin Jantjes’s ‘Untitled’ from the series ‘Zulu, the sky above your head’, 1998, a representation of the Kho San people’s creation myth, at the start of the exhibition, as a reminder that science has not replaced broader cultural beliefs, but added new dimensions.

t=0, a birth certificate for the Universe

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108Lemaître’s ‘Graphs of the evolution in time of the radius of the Universe’ sat at the entrance of Gallery 2 at the heart of the exhibition, providing stunning evidence of his ability to conceptualise a theory rooted in Einstein’s equation at a time when nobody (including Einstein) believed in the expansion. Alongside other world-first science objects in Gallery 2, Did time have a beginning?, they presented Lemaître’s challenge to the standard belief that the Universe is without beginning or end.

Writing in the accompanying festival book Thomas Hertog (2021, p 132) explains:

Each curve represents a possible expansion curve of the Universe, depicting how its size changes over time. (…) some universes keep on expanding forever while others, containing more matter, collapse again (…) All Lemaître’s universes (…) start from size zero at ‘t=0’, the zero of time which he indicated in the bottom left-hand corner of the diagram (…). Recent astronomical observations revealed that our Universe first expanded quickly, then slowed down, and in recent billennia began to accelerate again. Remarkably, this is the one Lemaître chose.

Lemaitre’s framed graphs were placed on the walls alongside artworks, engineering an immediate connection for visitors as well as allowing a very special triangulation between three otherwise unrelated works. Riffing off Lemaître’s poetic description of the initial single particle of the physical Universe ‘primeval atom’ as a ‘cosmic egg’, I proposed during research that we considered Constantin Brâncuși’s Le Commencement du monde (The Beginning of the World) series. These sculptural and photographic pared-down oval forms were coincidentally developed between 1920 and 1927, around the time Lemaître produced his graphs. What started as a simple visual association that didn’t appear particularly essential to the exhibition turned into an aesthetically and intellectually satisfying connection. The confirmation that ‘Brâncuși’s egg’, is at once an investigation into ‘the origins and mystery of human life’[22] and a contemplation of the beginning of time, supported the ambition to unearth parallel thinking across fields. Although we could find no evidence that either Brâncuși or Lemaître knew of the other’s work[23], it was interesting to consider the ways both used abstraction as a method to progress great insights. Annelies Vogels’s achievement in sourcing a stunning 1920 silver gelatin photograph of Le Commencement du monde, one of many international loans she was able to negotiate under the most challenging circumstances, meant we could juxtapose the visual and conceptual connections directly.

The third piece in this constellation trilogy, looking directly out at the ‘two eggs’ from the opposite wall was Maurits Cornelis Escher’s 1946 self-portrait ‘Eye’. A human skull replaces the ‘true’ reflection that the artist would have seen in his pupil in the mirror, which would have been his face. The impossible concept of man observing himself after death and the timeless eye pointed towards the graphs of the start of the Universe anticipated John Wheeler’s quantum ideas of the role of the observer in shaping reality, which emerges in subsequent galleries. While appreciating that few, if any, visitors would have consciously ‘got’ the full extent of the Wheeler connection it added to a repeating logic. Set against other works such as Troika’s film Time only exists so that not everything happens at once (which mediated on what we can discover when we conduct an observation over time), it fed into an observation theme which was repeated throughout, hopefully fixing the logic in visitors’ minds.

Two paths to truth

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108A main artery of bespoke display cases built into the centre of the gallery as part of Exponanza’s grid in Did time have a beginning? held most of the science objects which documented the core story. Hertog had a hunch that letters between key players of the day would be enlightening and, with Vogels, consulted archivist Véronique Fillieux, of UCLouvain’s Georges Lemaître Archives[24] and the UK Royal Astronomical Society Librarian and Archivist Sian Prosser. These conversations led to five extraordinary letters being brought together for the first time. Electrifying exchanges between Lemaître and Eddington, the Dutch mathematician Willem De Sitter and the Scottish astronomer William Smart documented growing acceptance of what would become the ‘Big Bang’ idea.

The letters were shown alongside a typescript for Lemaître’s seminal 1927 paper (written in French) ‘Un univers homogène…’[25], and with accessible hand-annotated overlays by Thomas Hertog and the Nature article in which in just 457 words Lemaître introduced his proposal in English. Porous science was in action as discovery, disagreement, conjecture and failure to perceive what might later be revealed to be true, ran through these heated scientific conversations. Several objects spoke to Lemaître’s careful division between the theological and scientific belief systems he lived his life by. A small commonplace notebook containing scientific insights at one end and spiritual reflections on the other was notable for the few blank pages he was always careful to leave between the two in all of his notebooks. Adjacent artworks by Clare Strand and Jeronimo Voss were positioned to echo and embellish these ideas with themes of realism, the ability to imagine the potentially impossible and the necessity of aggregate views to progress a consensus. We hoped they might amplify Lemaître’s quiet act of recognition that we exist in a condition of holding multiple truths which our beliefs play a role in ratifying.

Collegiate practice – Stephen Hawking’s blackboard “Don’t Forget to Double-Czech Your Results”

[26]Stephen Hawking’s blackboard was of immense importance to the exhibition and we were fortunate to receive a rare loan from Science Museum Group very shortly after it entered their collection from the Hawking estate. Seen in the section Time Began with the Big Bang, set after the 1965 discovery of relic radiation that Lemaître had predicted[27], and placed alongside Hawking’s own 1966 PhD thesis[28], it brought the science story into the later twentieth century.

As an object the blackboard is as unique, visually striking and powerful as Lemaître’s graphs. An outcome of the 1980 Cambridge Nuffield Workshop on Superspace and Supergravity organised by Hawking and Martin Roček, it was popular with visitors, press and visiting scholars alike. Mathematical equations, cryptic cartoons, a riot of colourful graffiti and puzzling physics jokes co-authored by the participants of the conference cover its surface (see the article by Juan-Andres Leon in this collection for an in-depth interrogation of the blackboard). Even Hertog was unable to completely decipher the multiple meanings. I found his personal insights as to why Hawking had kept and treasured this blackboard for so long very affecting:

This was a time when they literally thought they were on the verge of basically solving physics… I think this was the conference where Stephen was really at his peak scientifically, but also as a force in the scientific community.[29]

Hawking remains as renowned in popular culture as within leading theoretical physics circles. The blackboard’s role as a document of collegiate practice, as an emblem of the unquenchable thirst for knowledge and of being part of a team who had worked together in living memory was exciting for audiences. It humanised a field of science which can feel inaccessible. Its boisterous exuberance speaks to anyone who has thrown ideas around with friends. It was this, as much as any potential clues to the content that visitors thought they might gain access to, that made it such a central draw and essential object.

In our transdisciplinary narrative, it was also distinguished by the fact that, similarly to Lemaître’s graphs, to the uninformed eye, it was potentially indistinguishable from the myriad other artworks on display. We played on this by placing it alongside another blackboard. Artist Ni Youyu marked up a small nineteenth century astronomical photograph with a hand-drawn grid and painstakingly transcribed every miniature constellation onto his blackboard using white chalk dust and glue. His durational personal process, enacted during a period of over 100 hours’ labour, leads us to a recognition that the act of describing, by both artists and scientists, is also an act of eternal discovery. If asked which was the science object and which art, I think many visitors would have mixed them up.

Presence in absence

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108The blackboard’s location in the story also occurred at a point in the exhibition where, owing to the scarcity of some key objects and the pandemic conditions, we struggled to identify or secure key objects. We closely considered how artworks might function as ‘proxies’ with regards to key aspects of the science story. It was in these moments that our challenge to ourselves not to ‘use’ any art ‘illustratively’ was most acute. It is useful here to consider Maharaj (2002, p 72) on visual art as ‘a matter of inventing other ways of thinking-knowing, other epistemological engines’. Allowing key artworks to refer to key scientific ideas through ‘see-think-feel-map modalities’ (Maharaj argues) led to multiple more eloquent, expansive or philosophical interpretations than direct objects might have offered us.

Here Vogels proposed the work of Belgian pioneer of abstraction Georges Vantongerloo, who from the 1920s strongly engaged with the wealth of scientific discovery in cosmology, materials science and atomic physics. Vantongerloo’s work evokes the abstract reality of ideas and concepts prior to their transformation into the physical world of our experiences. ‘Formation de la matière’, with its concentric circles evoking the inner structure of atoms, resonates with the work of physicist George Gamow, who imagined the early Universe as a nuclear oven in the same period. Gamow was important to the story as his crucial advance would provide a physical reification of Lemaître’s idea of a unique primordial quantum[30], but we were unable to obtain any science objects related to this. We found Vantongerloo’s work could be interpreted in a way which both referenced Gamow and enhanced the conceptual understanding of the artist’s work, about which little is written.

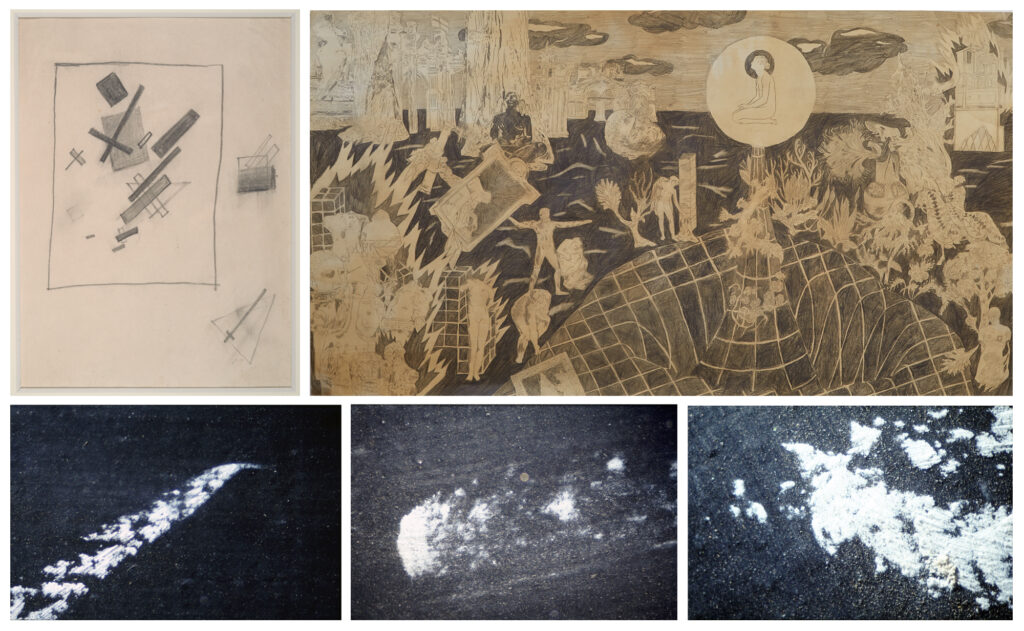

When it came to evidencing Lemaître’s ‘fossil radiation’ few objects are as evocative as the pigeon trap engineers Penzias and Wilson used to snare the pigeons they initially thought were causing the hissing on their radio antenna that was in fact evidence of the Big Bang. Photographer Stephen Tillmans uses photography to capture residual radiation from the Big Bang that is visible between channels on analogue television sets. Snapped at the split-second when an old television is switched off and the picture collapses into its essential element of light, his frozen moments in televisual time are also visual sculptures of the beginning of time. We placed his ‘Luminant Point Arrays’ in the vicinity of black and white archive television footage of Lemaître discussing his findings, happy to allow Lemaître’s televisual image to face haunting visual evidence of his prediction.

Imaging deep time

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108An immersive gallery between the historic and more contemporary science galleries addressed the role of photography, film and data-driven imaging technologies in shaping how we see the cosmos. Referencing the giant terrestrial and space-based telescopes, observatories and banks of powerful computers which support the science of cosmology and the production of these images, it presented a series of artworks predominantly created in collaboration with scientists. Collectively these offered visitors a direct encounter with observations of the light from deep space and deep time and addressed how our shared ideas of outer space have been heavily influenced by the astonishing imagery of the Hubble Space Telescope and research centres such as CERN.

Approaching abstraction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108We are not angels who view the universe from the outside. Our theories are never decoupled from us.

Stephen Hawking[31]

The philosophical questions pertaining to our relationship with reality and observation, influenced by Wheeler’s participatory Universe, came to the fore in the second half of the exhibition. These, along with Hawking’s advocacy for imagination, ‘we create the Universe as much as it creates us’[32], took the science into increasingly abstract spaces, stretching again our ability to display science objects. The penultimate gallery, Imaginary time?, asked: ‘If time began with the Big Bang what came before?’

It focused on Hawking’s concept of ‘Imaginary time’ and how the blurring of the lines between subject and object in quantum theory encouraged scientists to reflect on how our position within the Universe affects how we observe it — an idea, our panel noted, that has featured in Eastern mysticism for eons.

Three complicated objects held the science content in this space: John Wheeler’s 1977 drawing of the evolution of the Universe as a self-observing U-shaped object[33]; Stephen Hawking’s 1983 No-boundary proposal manuscript; and a facsimile of Hawking’s 2009 Time travellers’ party invitation, a conceptual art act in itself which documented a thought experiment (or art ‘performance’?) where Hawking sent out party invitations for an event that had already passed during which he waited for people who had mastered time travel to show up.

To a non-specialist audience, each of these would struggle to materially communicate their bold concepts on their own. Their object labels allowed us to elaborate somewhat, but a judicious selection of artworks whose innate concepts chimed, and whose reading could be deepened by their association, allowed us to elaborate further.

Historical and contemporary artworks demonstrated congruous concerns. Belgian Surrealist René Magritte’s 1965 pencil and gouache painting ‘La belle captive’ plays with the artifice of a painting that captures a poetic reality, rather than what we deem to be an elusive ‘objectivity’. We interpreted it as echoing the notion that our inability to step outside the cosmos must shape what we seek to unravel. Along with Charmaine Watkiss’s ‘Infinity’ (2017), a film of two left hands endlessly configuring and reconfiguring space through repetitive games of cat’s cradle, it sat opposite the science objects.

In the same room was Rohini Devasher’s ‘Atmospheres’, filmed from our perspective on Earth, which offered a ‘conceptual mirror’ to the famous 1972 ‘Blue Marble’ photograph of Earth taken by astronauts from space. Also in the room was Andy Holden’s series ‘Eyes in Space’, which he produced by ripping space pictures out of science textbooks and placing googly eyes on them. Both, while created independently from Wheeler’s theories, continue to conceptually probe the questions raised by his work.

Meeting complicated with complicated was work by the late British conceptual pioneer John Latham, who is known to have written to Hawking, although they never met, His ‘ProtoUniverse’ (2003) explored Latham’s own cosmological ‘least event’ theory developed in the 1970s, whereby the most basic component of reality is not the particle, but the shortest departure from nothing. Highly conceptually challenging, it reinforced our position that long-standing artists’ theories, while operating differently to scientific theories, also play a role in our collective perceptions and knowledge, and provided opportunity to share through the object label Hawking’s defence of his no boundary proposal: that ‘asking what came before the Big Bang is like asking what lies South of the South Pole – a meaningless question’.

Is time an illusion?

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108Profound questions about our ultimate origins take physics out of its comfort zone, yet this was exactly where Hawking liked to venture.

Thomas Hertog[34]

The final exhibition space, Is time an illusion? looked at how, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, we are entering a new era in cosmology, where most leading theoretical physicists now believe that it is inevitable that Einstein’s ideas about spacetime will be replaced by a quantum hypothesis. Here we flagged holographic theories which, based on Hertog’s position, argued that we must now ‘revise our image of spacetime, and even accept that most of it is an illusion’.[35] This was the most difficult section and idea to communicate to general visitors. But as previously mentioned, our goal was not to provide concrete scientific explanation. Rather it was to involve visitors in multimodal enquiry, where minds could be opened to possibility, and a willingness to challenge received knowledge and to reimagine potential futures could be encouraged.

Again, we fielded just three science objects: a vinyl of the first image of a black hole made with the Event Horizon Telescope, a LEGO model of the James Webb Telescope, and an interferometer mirror from the European Gravitational Observatory Virgo experiment. These represented a new era in cosmology of increasingly sophisticated techniques such as using gravitational waves to look beyond what we can perceive or collect through light. Rather than explaining a myriad of theories or techniques, the artworks here invited visitors to consider how the freedom to explore previously uncharted cosmic concepts and territories is as central to contemporary cosmology as it is to contemporary art. Here too, the art took on a more provocative role, sitting in a critical space more independent of any physics theory than those presented in previous galleries, but where profound connections came from their engagement with the vast open space between abstract thought, data, bits, bytes and radical imagination.

Dawit L Petros’s photographic series continues his work into a critical re-reading of the relationship between African histories and European Modernism. An empty cardboard box employed by the artist as a performance prop becomes a vortex through which we can enter or exit various temporal locations. It speaks to how we arrive at conclusions through context and relative point of view. The forms his body and the box make are based on the Tigrinya alphabet of Eritrea, the artist’s country of birth, where consonant letterforms are modified depending on neighbouring vowels. As part of Petros’s ongoing dialogue with Modernism it also deliberately references Malevich’s ‘Black Square’.

Suzanne Treister’s ‘The Holographic Universe Theory of Art History (THUTOAH)’ occupied, in our exhibition, the role of both art and science object. Created during a residency at CERN, it suggests artists have long imagined the Universe as a hologram, where one of the dimensions of space or time is an illusion. A new version for our show featured Hawking and Hertog’s last theory (which Treister’s independent research echoes)[36] through an overlaid soundtrack of a conversation between herself, Hertog and the voice of Stephen Hawking.

Navigating what is intuitively felt but not necessarily scientifically clarified was also a theme in an immersive room of dynamic moving shadows created by Conrad Shawcross and in a sculpture by London Fieldworks. The latter was created by a manufacturing robot which worked from live brainwave data captured while the late avant-garde artist Gustav Metzger attempted to think about nothing.

Imagination and progress were not universally presented as uncomplicated assets. Jackie Karuti’s video ‘The Planet’s – Chapter 32’ takes viewers on a fragmented journey through moments of global exploration, colonial extraction and AI innovation. It acted as a critical reminder that our dystopian histories and tendencies have the power to disrupt our utopian ideals and that our methods of discovering can have harmful, careless or unintended consequences. Equally Sarah Pickering’s ‘Black Holes’ sequence, unique photographs created by gunfire shot at photographic paper, look very different to the scientific black hole images captured by the event horizon telescope, but they fit our ideas of black holes, revealing how assumptions must always be challenged.

The two final artworks in the exhibition returned us to the central questions about our place in the cosmos. Gavin Jantjes’s ‘Untitled’ from the start features strong human presence. Phoebe Boswell’s specially commissioned portrait of an East African mother’s grounded feet (‘Mum’s Feet, Grounded’) is a powerful symbol of our collective beginnings. It speaks to a sense of eternity, timelessness and a universal sublime. Mark Wallinger’s ‘Ego’ is a mischievous recreation of Michelangelo’s ‘The Creation of Adam’. Here, two cheap digital photographs present the artists own hands performing each role; we are left wondering which is the creator and which the created?

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242108The objects linked together so beautifully that the science objects almost became art objects and vice versa.

Ward Denys[37]

To the Edge of Time introduced the Big Bang discovery story to festival audiences as one of the greatest scientific revolutions of our time. It was the first exhibition worldwide to explore Lemaître’s work through a transdisciplinary narrative, and to contextualise Stephen Hawking’s work in a broader historical context. It was also unusual for a cosmology exhibition in its reliance on material culture through science objects and historical and contemporary artworks in all media. In being part of a popular festival associated with a distinguished university it was supported to be both shamelessly intellectual and shamelessly theatrical.

An exhibition is an experience and thus extremely difficult to conjure up in words, but this article attempts to bring To the Edge of Time to life a little, demonstrating how, through a co-curated narrative, selections and juxtapositions, we shared with visitors some of the ‘truly amazing ideas’[38] the featured scientists and artists have brought to the field. Much to our regret, the pandemic production and display period, straddling multiple lockdowns, rendered plans to conduct formal evaluation impossible. Some success markers though anecdotal can be shared, however. The exhibition won the Belgian Academy Award for its art science narrative and as a charging exhibition was continually sold-out.

As a curatorial team, it is our view (based on experience and casual observation of visitors) that the experiential quality of the artworks allowed some of the material and philosophical threads in the science narrative to be felt and understood in an embodied way which could reach out to scholars and non-science specialist audiences alike. Throughout the exhibition we curated a continual sense of energy, circularity and motion, with ripples, waves and explosive moments ensuring that visitors’ perception, perspective, sense of time, space, stillness, motion, looking outward or inward, were quite often literally being turned around. Exponanza’s choice of dusk to dawn colours for the wallpaper added a sense of rotational, planetary movement. Visitors were excited by the stunning ‘attractor’ artworks and the fact the exhibition looked and felt like an art gallery, but also introduced highly complex science. Local connections, such as letters between Einstein and Queen Elisabeth of Belgium[39], were also important to a sense of place, while Lemaître’s graphs and Hawking’s blackboard became focal points not only of the exhibition but also of the wider festival. Unsurprisingly, visitors found the science easier to follow in the first half of the exhibition than in than the later, more abstract sections. But we enjoyed the ways artworks began to carry the material representation of a story that seemed now not only closer to science fiction but also to philosophy.

Arnold and Olsen (2003) observe the potential for museums to be ‘privileged sites of experimental knowledge’[40] in cross-discipline approaches. In continuing a decades-long tradition in exhibitions, our transdisciplinary approach was hardly experimental in itself. It was, however, a highly experimental approach for the host organisation, which brought its own unique context as an internationally significant seat of learning, and which hoped that staging such a show would encourage visitors outside of the academic community to come.

That hope was well-founded. In spite of the pandemic, there was good coverage in the mainstream press, particularly general cultural reviews and the science pages. The specialist arts press was less engaged. My personal view is that this was not only because there was competition within the huge arts offer across the festival because of the pandemic conditions. Transdisciplinary narratives displayed outside of mainstream arts structures frequently struggle to attract widespread coverage, even if, as here, major league as well as emerging and less recognised artists are featured. Ironically given the focus on collegiate effort and the clear intention to provide a science and art narrative, much press that did cover the show seemed more excited to report that ‘a scientist’ had curated an art and science show than to acknowledge our curatorial collaboration. On a positive note, perhaps these responses quelled early concerns raised by one project sponsor in response to the art’s powerful presence, that there ‘might not be enough science’.

Ultimately To the Edge of Time was not a science exhibition and it was not an art exhibition. But I think we succeeded in our ambition to tell our story through a truly combined narrative drawn from the unique perspectives of our interdisciplinary team and the contribution of living artists whose collaboration in positioning and interpreting their work was essential. As co-curators, Thomas Hertog and I held intensive conversations online and through email exchange as our collaboration called upon us to negotiate ‘ideas, methods and identities’ (Pleiger, 2020). Gaps in our knowledge and experience did create tensions and frustration, although I can say that at no stage did either of us feel as unfortunate as Pleiger’s anonymous science curator who ‘felt like a rejected organ during a transplant’ (Pleiger, 2020). As we shared our assumptions, acknowledging how labels in transdisciplinary narratives ‘can be sites of potential linguistic, attitudinal, perceptual or cognitive conflict’ (Redler-Hawes, 2020), our differing interpretations shifted, allowing us to identify a language for in-tandem readings which expanded, clarified and creatively troubled previous meanings of the artworks and objects.

Our ability to ‘unify’ relied on our own willingness and experience, but it also required the support of the wider team. We tested our script against our expert checkers[41], the artists, the wider KU Leuven science community and exhibition and design teams. Vogels and De Keukelaere mediated many conversations, bringing further art historical and exhibitions expertise. Where I identified a science communication need to break the vast content down for the benefit of myself and visitors, they appointed Siska Waelkens[42] to reduce the science into ‘content chunks’. These informed tools I brought to the process from my museum training, such as key messages, the interpretation strategy and the criteria against which I researched artists.[43] I also approached the author and museum professional Graham Farmelo[44] to help us to craft the messages. As a scientist with expertise in bringing complex ideas to large audiences, he provided a curatorial bridge, through fluent interpretation of both my language of exhibitions and Hertog’s language of physics.

In the final exhibition artworks and science objects were presented as equal partners that could fluidly share responsibility for conveying key moments, materials and ideas. By accepting that mixed media observations, data, conjecture and subjective interpretation all play a part in how we enact discoveries, we achieved our objective of revealing the powerful arc that binds generations of scientists and artists wondering, searching and working towards an ever-deeper conceptualisation of the cosmos. The combining of historical art and science objects with very recent and newly commissioned contemporary art and advanced theoretical physics ideas helped to convey parallel movements of thought where neither the art nor the science were presented as derivative of each other. The curatorial alignment of the artworks with the ebb, flow and processes of scientific research allowed both to be understood in broader contexts. Themes moved between hypothesis, evidence, speculation and existential questions. Artists enacted new forms of individual, social and political observation, conducting thought experiments which should never pass scientific peer review but which nevertheless resulted in breathtaking revelations and provocative, often very funny, new perspectives. A number of works evoked or extended into the sublime, immersing visitors in the fearsome or inspiring pleasures of the unknown, the imperceptible and the uncharted.

Ultimately I believe that the exhibition offered a persuasive argument that was intellectually bold. It showed how combined narratives that allow space for complexity, a humble approach to collaboration supported by broad expertise, and careful research can deliver an emotionally rich, multisensory and appealing transdisciplinary experience, bringing new insights both to visitors and curatorial teams. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to work on such a project.

Acknowledgements

To the Edge of Time was co-curated by Hannah Redler-Hawes and Thomas Hertog working with Annelies Vogels, Coordinator of Exhibitions at KU Leuven and Wouter Daenen of the KU Leuven Libraries exhibition team. It was commissioned by Hilde Van Kiel, director of the University Library and Lien De Keukelaere of Kunst Leuven with funding from those organisations and with support from the Belgian Ministry of Tourism and Belgian Ministry of Science.[45]