Wounded – an exhibition out of time

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313

Abstract

The creation of an exhibition, from the original idea to the final public offering involves a series of developmental stages subject to a whole range of influences. During these processes different choices are presented as an initial concept is translated into real content with its accompanying interpretation. As the exhibition becomes fleshed out, significant departures from and adaptations to the original vision are almost inevitable, whether these are desired or imposed by circumstance. This paper will outline and discuss some of these processes in relation to a particular scenario; where the bold concept for one exhibition has been subsequently re-purposed as the basis for a different display. In this case a concept was shifted from a contemporary setting to a historic one and scaled up from a close, contained situation to one of vast sprawling size and complexity. How might original exhibition themes and ideas persist and develop in the new scenario and in what forms might they manifest themselves? Do the original characteristics hinder the development of that second exhibition or might they even flourish – perhaps in unexpected ways?

This article explores a case study: the Science Museum’s temporary exhibition Wounded: Casualties, Conflict and Care, which was open to the public between 2016 and 2018. Looking beyond what is simply suggested by the exhibition’s title, it examines how underlying elements present in an original concept for an exhibition emerged or evolved in the development of this final display. The main focus of this case study is to examine the nature of these elements and the challenges, opportunities and occasional contradictions that they presented throughout the exhibition process.

Fundamentally these elements related to concepts of time and of ‘scale’, both of which would ultimately infuse the interpretation of Wounded and be found layered throughout the exhibition, albeit expressed in subtly different ways. Manifestations of time were here conceived as linear and concisely measurable, and emotionally experienced or imagined. Scale appears, most tellingly, in the contrasts offered between the individual and the mass. Ultimately, I argue, these merge into notions of the ‘anonymous individual’, which had its own power to help emotionally engage visitors with the exhibition.

Keywords

exhibitions, First World War, Interpretation, Medical care, Military medicine, Rehabilitation, Time, Wounded

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/It may sound heartless and inhuman, but…from a military standpoint it is better for a man to be killed than wounded. If a man is killed he is buried, and the responsibility of the government ceases.

Wounded: Conflict, Casualties and Care was a temporary exhibition held at the Science Museum. It opened on the 29 June 2016 and closed on 3 June 2018. During that time it was seen by well over half a million visitors. Wounded was the Museum’s primary contribution to mark the centenary of the First World War. As the Lead Curator on this project, I endeavoured to create an object-rich display centred on the phenomenon of wounding and its implications in the immediate and longer terms, both for medical practice and practitioners but also for the wounded themselves. From the outset, the exhibition was intended to be of interest to a general, non-specialist audience.

Developing the overarching narrative structure and detailed content of Wounded inevitably presented a whole series of curatorial choices. In this paper I will reflect on some of the different influences that both generated and guided content strands in Wounded from its earliest iteration, and the subsequent approaches taken to interpret them. With the benefit of hindsight, I will trace how some narrative ideas and interpretive choices persisted throughout the various phases of exhibition development, while others were lightly adjusted, significantly modified or totally abandoned. And I will return consistently to how an earlier concept, for a different exhibition, acted as the blueprint for Wounded and how the essence of that original idea was to manifest itself in different and at times unexpected ways throughout the final display. I will also touch on the influence that contemporaneous medical writings had on this process, in terms of object and story selection within the Wounded exhibition.

In overview, Wounded examined episodes from the medical experience of the First World War. It addressed the nature of wounds, some of the approaches taken to treating these wounds, the strategies employed to transport the wounded and then their continued care once they came back home. It also raised some of the wider societal issues resulting from this mass return as well as the expectations and realities for the wounded themselves in the subsequent years and decades as they resumed their civilian lives. But while repeatedly referring to this main narrative framework, I will focus much of this paper on particular interpretive challenges and opportunities that presented themselves as the exhibition took shape. I will do this by highlighting and meditating on a number of distinct and recurrent thematic elements, whose characteristics and qualities permeated Wounded and were layered in different ways throughout the exhibition. Through these reflections I hope to draw some general conclusions about the exhibition-making process which I hope will also be relevant to practitioners beyond the specific subject area of this case study.

A century of wounding

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/002The primary subject of Wounded was the First World War, yet its origins lie in an earlier exhibition proposal which focused on more recent conflicts. In 2008, I submitted to the Science Museum’s Programmes Committee a single page outline for a temporary exhibition, provisionally entitled War, Medicine and the Wounded Soldier (Emmens, 2008). This exhibition would reference episodes of frontline military medicine from various points in history, but at its core would be the battlefield medicine then being experienced by Allied forces in Afghanistan and Iraq. Indeed, the inspiration for this exhibition came largely from media reports about British casualties at the time. A typical example being:

British soldier killed in Afghan ambush[1]

A British NATO soldier was killed and four wounded at the weekend after a Taliban ambush near the southern Afghanistan town of Sangin, the British military said on Sunday.

In the wake of such reports, the names of the dead tended to be quickly publicised and their bodies returned home with much ceremony, but I was struck by the references to the wounded. They appeared to largely disappear from the subsequent story. How had they been wounded and what had actually happened to them in the aftermath? What had been their medical treatment? Who had cared for them then and was caring for them now? What places had they been taken to for treatment and by what means had they been transported there? And if they were dealing with life-changing injuries, what might they face in the longer term?

Such questions informed my initial exhibition proposal, which was to follow a time-linear narrative. Starting with a split-second ‘moment of wounding’, the exhibition would follow the journey away from this point, to pick up on events in the seconds, minutes, hours, days and months that followed. It would look at key medical interventions and progressively introduce some of the specialised personnel, technologies and sites of treatment that a wounded soldier might encounter, both during the fight to save their life but also in their longer recovery and rehabilitation. It was envisaged as being focused on intimate, personal stories – perhaps presenting a single archetypal journey away from that ‘moment of wounding’.

As a curator working closely with our medical collections, I felt such an exhibition would be a real opportunity to present medical treatment as a staged process, rather than as techniques and specialisms which in other contexts might seem unconnected. Instead, distinct forms of practice such as battlefield trauma care, reconstructive surgery and psychological rehabilitation, could all be presented as ‘mile markers’ in a long journey. A journey that in theory could be taken by a single individual.

This proposal was one of a number of ideas for temporary displays put forward by different curators. Although it was well received by the committee, the exhibition was not progressed. However, in its essential concept, narrative structure, the themes it addressed and the underlying issues it raised, it was hugely influential in the development of Wounded several years on.

In this later, realised exhibition the wounded remained at the emotional core, with the final object and narrative choices guided by different causes and forms of wounding and their subsequent handling, treatment and rehabilitation. With the extensive holdings of the Science Museum to call on, the material culture associated with these episodes populated the showcases throughout the Wounded exhibition.

Time and scale: recurring themes

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/003In constructing narrative frameworks that were strongly led by my earlier proposal, two thematic elements repeatedly presented themselves: those of time and of scale. Tracing and examining the qualities, characteristics and influence of these recurring tropes lies at the heart of this paper.

Time and perceptions of time were present throughout the exhibition, encompassing actual measurable time-spans, time-dependent events and perceptions of time passing, whether actually experienced, recalled from memory or imagined. As in the original proposal, linear time formed a backdrop to the exhibition, although less explicitly now and given varying degrees of emphasis. Passages of time, be they in seconds, hours or years, were inherent to the events that followed each personal ‘moment of wounding’. They were present at different sub-levels within the stages making up those numerous journeys but they could differ wildly. For example, the vital seconds to apply a tourniquet, the hours that could be spent waiting on a stretcher or the years before which mental health wounds might finally reveal themselves. Time, layered in different magnitudes and manifestations, whether quietly implied or explicitly stated, fundamentally underpinned and defined much of the character of the final exhibition.

Another time-based quality that both influenced and then permeated the final interpretation related to the wounded themselves. Those who had fought in Afghanistan or Iraq are still relatively young. The physically and mentally wounded young men of the First World War grew old and are now all dead. One big challenge of this exhibition was how to help visitors of a much later generation turn back time to override those last images of old veterans – speaking on documentaries or being pushed in wheelchairs at Remembrance services – and appreciate that when first wounded they were mostly young and often still had many decades of life to live. Indeed, they were just like those wounded in conflicts today.

A further strand in this discussion looks at what we might call scale. Objects, words or images in such an exhibition could convey unique, personal and very human stories. We could potentially choose to extract and present individual experiences and even highlight personal connections with surviving objects. Such an exhibition approach would lend itself well to a treatment of this country’s far smaller scale conflict in Afghanistan. But in the context of the First World War, this form of interpretation would inevitably be set within a far wider event, one whose sheer inhuman scales can impose a sense of personal anonymity that we may associate with ‘the mass’. As such, I wondered if an over-emphasis on individual medical experience would sit easy with the realities of scale at the other extreme, with the huge volumes of materials and resources employed by, and the mass casualties inflicted on, the vast and anonymous armies gathered on the battlefields for four and a half years.

Expressed in different ways, elements of time and scale are all present within the over-arching structure of the exhibition, but they are also insinuated throughout the more focused narratives. To varying degrees these features were central in the concept for the final exhibition from the very start and their presence was clear and deliberate. Yet on reflection, I would contend that they continued to emerge in variant forms as the exhibition developed – sometimes only really revealing themselves when it was completed. In places they dictated object selections and shaped the interpretation of the stories being told, but elsewhere they lay virtually hidden, almost subliminal, yet even there they could help to add crucial layers of emotion and meaning.

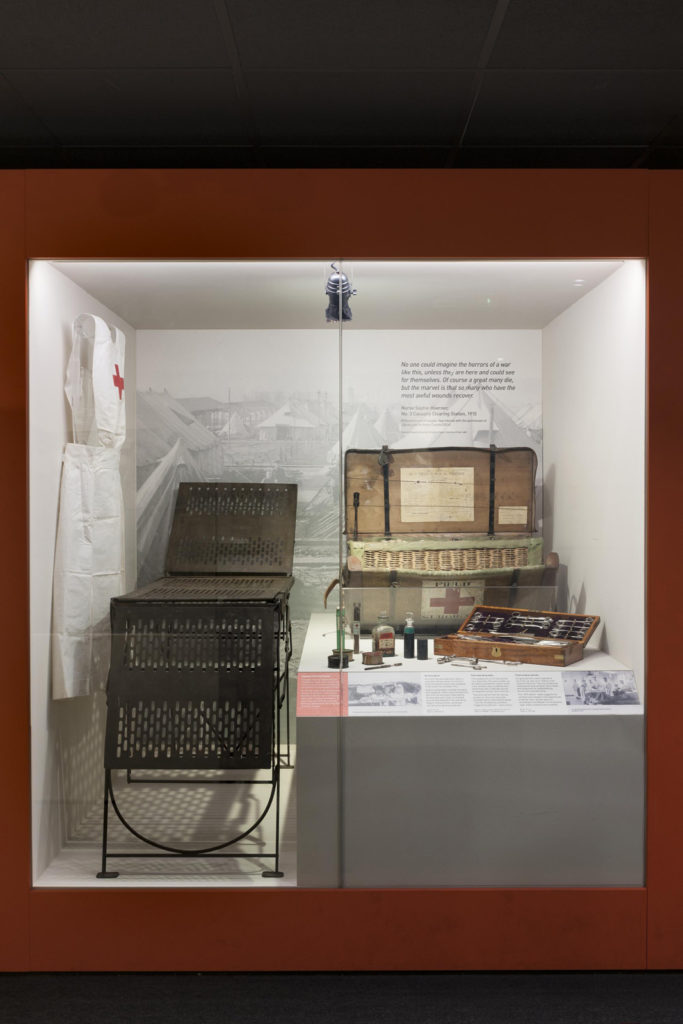

The material culture of trauma in the Science Museum

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/004The Science Museum’s collections are perhaps surprisingly rich in the medical material culture of the First World War. Like most of our medical holdings the bulk of these objects are from the collections of the Wellcome Trust that were assembled by Henry Wellcome, which are on permanent loan to the Science Museum. However, they in turn came from a larger grouping of medical objects which had been accumulated at the end of the war. Some of these were originally displayed at the Crystal Palace in June 1920, in an early incarnation of the Imperial War Museum.

That fledgling museum selected key pieces of this medical technology for their own growing collections, but much of what remained was acquired by Wellcome. The resulting haul contained objects from both the Central Powers as well as the Allies, much of the former having been hoovered up by the victors after the Armistice. It is a rather eclectic and unstructured grouping. An early decision by the British authorities to reclaim a proportion of their medical equipment for future use means that much of the quality and depth of our holdings actually lies with German objects. Although Wounded told a British story, a small number of German objects did feature.

Only a small proportion of our collection has previously been displayed in the Museum, notably in a single case in the old medical galleries that were closed in early 2016. Other objects remain scattered throughout the Science Museum, particularly in the Making the Modern World gallery. A few have been loaned, but the majority of this material has remained in storage since it was acquired. The medical collections at the Science Museum are amongst the largest and most important in the world, but until Wounded no exhibition dedicated to medicine’s role in war had been held there. In recent years, it’s primarily been an area addressed by specialist museums[2] or within museums dedicated to military history in its broader contexts.[3] One clear exception was War and Medicine, a temporary exhibition shown at London’s Wellcome Collection (2008–09), which included a number of objects held by the Science Museum.

Wounded was an opportunity to showcase a significant proportion of our First World War objects, but in developing the final content several new acquisitions were made and a number of loans were secured from various public and private sources.

Blasting, cutting, burning and poisoning

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/005The main purpose and outcome of war is injuring…to alter (to burn, to blast, to shell, to cut) human tissue, as well as to alter the surface, shape, and deep entirety of the objects that human beings recognise as extensions of themselves.

The First World War was a new kind of war, with powerful new weapons that produced levels of wounding unparalleled in scale and severity. It was also a war fought within environments and under conditions which could be highly detrimental to the effective evacuation, treatment and care of those who had been wounded. This combination of elements created an ongoing medical catastrophe, the brutal potential of which was tragically brought home to British forces on 1 July 1916 – the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

In the face of such challenges new medical techniques and strategies were pioneered, but others were rediscovered, adapted and evolved through experience. Many of the principles of wound treatment established in previous conflicts also had to be actively ‘un-learned’ by medical personnel working in these new conditions.[4] This was a war that also threw up the previously unseen wounds of poison gas as well as unexpected levels of mental health wounding – often referred to at the time as ‘shell shock’.

For many soldiers, being wounded could be the start of a long and life-changing journey – both physical and temporal. Those who survived could return home to a life that was very different from what they had had before, lives that were to be played out in the wake of transformative events on a distant battlefield.

The ambition of Wounded was to explore episodes from these journeys away from the battlefield, be it the urgency of dealing with the initial wounding to the longer-term treatment of wounds and their later complications. Some aspects would be addressed in detail, by presenting key techniques, technologies and strategies that emerged both during the conflict and in its wake. But we also hoped to at least evoke the sense that the effects of wounding were long-lasting and that a century on – in a direct echo of my original proposal – soldiers in conflicts today are still being wounded in similar ways and still face those lifelong journeys.

The opening of Wounded was timed to coincide with the centenary of the beginning of the Battle of the Somme, and that event was highlighted in much of the press and publicity. However, it was not simply an exhibition about that battle. British and empire forces had already been experiencing both huge numbers of casualties and major medical challenges in previous battles and would continue to do so in the many months that followed it but, as perhaps the concentrated embodiment of the many threats to physical and mental health faced by the British Army during the war, the Somme inevitably loomed large. Timing the launch of the exhibition to coincide with the centenary also helped bring some early containment to its scope. Our environment became defined as the Western Front and our primary subjects became British service and medical personnel.

The Western Front was the main site of British engagement in the war and concentrating on this location – extensive though it was – inevitably guided much of the medical content of the exhibition. Had we either focused on or extended the coverage to other areas – for example, the campaign in Mesopotamia – the detrimental influence of climate, desert terrain and endemic infectious diseases on medical strategies would have provided alternative stories for interpretation. That particular theatre would also have offered greater opportunities to explore the involvement of forces drawn from Britain’s empire – although their presence on the battlefields of Europe and their treatment back in Britain’s hospitals was referenced in the final exhibition.

The long journey in time from the Western Front

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/006If you lifted your head to look just for a second, you got it in the neck every time

Serious wounds were very often received in a fraction of a second. Over four years, millions of bodies were caught by the fragmentation of an artillery shell, a spray of machine gun fire or a single rifle bullet. A moment that for many of those who survived marked a transition between two distinct phases of life. Yet a moment whose immediacy could pass almost unnoticed and one most soldiers would later find difficult to recall or communicate to others (Reid, 2017, pp 115–6).

After some scene setting and introduction Wounded, like it’s unrealised predecessor, truly began with a conceptualised ‘moment of wounding’. Fragmented short quotes, originally written down by those trying to recall their wounding just hours or days earlier, were projected on the floor and walls of a short passageway leading into the main thematic phases of the exhibition.

Triggered by the presence of visitors, these projections were accompanied by the ambient sound of battlefield rumblings, a sequence which faded into the frantic ticking of an Edwardian-era pocket watch. A subtle touch, but one that was very much intentional and needed to be right. The original version of the commissioned soundscape ended in the more ponderous ticking of a clock. The watch was requested to bring a greater sense of urgency as well as reflect what might actually have been in soldiers’ pockets. For many of the wounded, a race against time had begun the moment they were hit. Time was ticking away.

I looked at my watch … it was spattered with blood.[5]

The subsequent narrative structure of Wounded followed a broadly linear trajectory that encompassed timespans ranging from seconds and minutes to years and decades. This clearly echoed the time structure that was to be applied to the contemporary military campaigns outlined in my original proposal. For British personnel wounded in Afghanistan or Iraq, the first seconds and minutes were critical to a soldier’s survival and integral to general trauma management plans. With the relatively low casualty numbers, a timetable of dedicated medical treatment, evacuation and care could realistically have been presented on gallery to illustrate a typical journey away from the battlefield.

Very early in the development of Wounded it was clear that such an interpretation would not be so straightforward in a First World War context. In the chaos and scale of much of the frontline action, the timing of any medical interventions were often down to luck and circumstance. And for many throughout the First World War, those early post-wounding seconds and minutes, let alone hours, could ultimately count for nothing as casualties either couldn’t be reached or their sheer numbers overwhelmed medical facilities. Today, early intervention is a cornerstone of trauma medicine in both civilian and military spheres. This is a crucial difference between the two exhibition scenarios.

In the century that followed, much has been written about the medical experience of the First World War and for the development of this project recent literature on First World War era military medicine was central,[6] but so too were contemporaneous writings by those working in the medical services, and even the wounded themselves.[7] In particular, Wounded drew on books and journal articles written by those with direct experience of the medical facilities that lay along the British chain of evacuation from the Western Front. Such an approach would be expected, but it felt doubly important as these authors were writing within that chaotic landscape of mass casualties, endless delays and medical limitations – long before any expectation of Medevac helicopters, CPR, antibiotics and other procedures familiar to medics today.

No two wounds are the same

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/007War wounds ranged from the trivial to the critical and on the Western Front powerful weaponry and a poisonous environment contrived to conjure up a myriad of trauma. Across more than four years, millions were wounded on those battlefields, yet the full story of each wounding followed a path dictated by a combination of circumstances. Soldiers received wounds in different ways, in different parts of their bodies and from different causes. Depending where on the timeline of the war they were wounded, in what location, and on what battlefield could determine how soon help might arrive, what form it might take and when evacuation might begin. The limitations of what medical intervention might be available and the windows of time in which to enact such interventions were also crucial.

Once back home new influences took precedent, such as the degree of disability left by a wound or shifting public attitudes towards the wounded, as well as more prosaic factors like age, social class and home location. All these factors, whether time-related or not, affected the subsequent course experienced after each initial wounding.

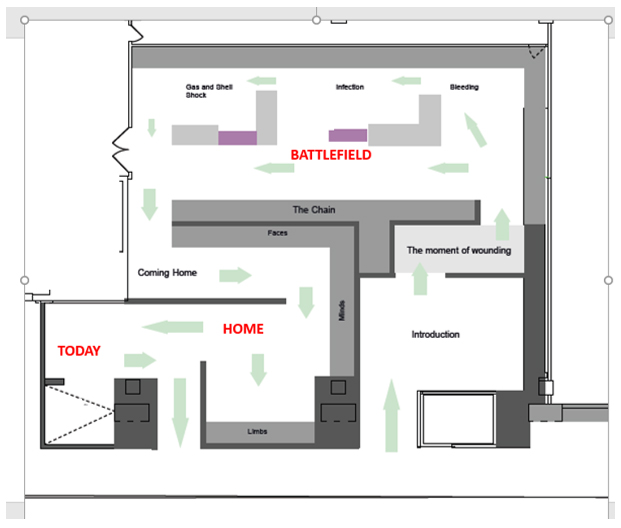

But in its underpinning of Wounded, time shaped a crude hierarchy and aspects of wounding covered in the ‘Battlefield’ section of the exhibition (see Figure 6) were all largely defined by associated timescales – be they seconds, minutes, hours or days. In the context of this section of the exhibition, aspects of wounding were broadly presented in a series of time-differentiated sub-sections which could be summarised here as blood loss, infection, the effects of poison gas and the impact on mental health.

In the latter ‘Home’ section of the exhibition (see Figure 6), longer term treatment and rehabilitation were illustrated by a clearer typology of wounding – limb loss, blindness, facial injuries and mental health wounds. But while less overtly time-based, different wounds with different treatments had trajectories that played out over different ranges within the overarching timescale of a wounded man’s ‘life journey’, which continued at home into longer weeks, months, years and potentially decades.

Although many wounds were instantaneous, poison gas, used from Spring 1915, had a more insidious effect. Its impacts effectively taking place in slow motion, with time stretched and lungs or skin betrayed during the ‘ecstasy of fumbling’[8] to fit a rudimentary mask or more slowly absorbed as unseen or unsmelled vapours infiltrated the trenches. Psychological wounds could be far longer still in gestation. The traumatic impact of what was called shellshock was clear to many of those fighting on the Western Front. But for an individual, official acknowledgement, yet alone personal awareness that they themselves carried this most hidden of wounds could be many years down the line – long after former soldiers had returned to domestic life. Even with a greater understanding arising from a further century of conflict, many ex-soldiers carrying psychological wounds still take more than a decade before seeking help, if they do so at all (Murphy, et al, 2013).

Blood loss

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/008Even for those assigned within our crude hierarchy of First World War wounding, different individuals could have very different experiences. An example would be blood loss, which on the battlefield is almost invariably the most urgent issue to address.[9] Yet within this most dangerous of conditions there were a range of timescales – and these sub-levels were acknowledged within the exhibition and reflected in our object choices. Whereas in some circumstances blood loss could be fatal in minutes, if not seconds, and a tourniquet might be the only hope, critical blood loss could also be deceptively slow. Men apparently only lightly wounded could die hours later from physiological shock (then usually referred to as ‘wound shock’). This became a more likely outcome if they were not kept warm, comfortable, hydrated or, as was increasing seen near the very end of the war, given blood transfusions.

One key object chosen for display here was indeed our very early blood transfusion set designed in 1917 by Oswald Hope Robertson, a pioneer in the field. Transfusion was considered the most important medical advance of the war and a century later remains at the core of trauma management (Stansbury and Hess, 2009, pp 232–6). It proved its potential during the First World War, but its enduring legacy has overshadowed the scale of its wartime use (Harrison, 2010, p 115). This situation was clear within wartime writings referred to during the content development phase of Wounded, which are glowing in praise and possibility but revealed the limited scope and scale of its actual use.[10] Time, or perhaps more accurately timing, was also therefore key when interpreting some of the medical techniques and technologies used to treat the wounded. As it was, for all its legacy, effective blood transfusion came very late in the war.

Unfortunately, wound shock – the condition transfusion would ultimately address – was not really fully understood for much of the war. Nevertheless, how it might be tackled or prevented in a pre-transfusion environment was found to be the subject of much wartime interest and research.[11] A study of contemporaneous accounts shows that, in the British medical story of controlling blood loss on the Western Front, older, less sophisticated technologies like the Thomas leg splint had a greater role in saving life than transfusion.

The routine use of this Victorian traction device progressively nearer to the frontlines prevented the deaths of thousands whose shattered legs could previously have caused fatal haemorrhaging during the long, bumpy journeys away from the trenches. It too had to be chosen for display. So did some of the other more mundane items that could be crucial in preventing men slowly bleeding to death – a blanket and hot water bottle for warmth, morphine to kill pain, water for hydration and the calming home comforts of cigarettes or a mug of Oxo.

Wartime literature also addressed other aspects of bleeding, but unlike today the role of the tourniquet did not figure highly in these accounts. As traumatic haemorrhaging blood loss can be rapidly fatal, easy-to-use tourniquets were routinely carried by all combat troops in Afghanistan where those early seconds were so often vital in saving lives. But from the wartime medical experiences of a century ago we might perhaps read a tacit acceptance that it was not a war where very rapid medical interventions were the expectation, let alone the norm. On the battlefields of the Western Front there was little guarantee that those with severe wounds would get vital life-saving haemorrhage management in those crucial seconds after wounding. Indeed, when tourniquets were applied they often caused greater harm as delays could mean they remained tightly in place for hours. Even if the wounded did survive that initial critical stage, official figures suggest that on the Western Front alone over 150,000 British servicemen ‘died of wounds’ having first reached some form of medical unit (Mitchell and Smith, 1931, p 12).

The lifelong chain of evacuation

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/009The soldier who did get through the crisis of blood loss, whether in the first minutes or hours might then have faced the more drawn out but equally deadly threat of wound infection over the subsequent hours and days. If so, a life-saving amputation may have been required. Once back home, as well as dealing with a new artificial limb, such a patient might also be diagnosed with shell shock. Each wounding was a unique, often very complex and certainly very personal experience.

Such ongoing medical journeys would also involve a range of transport to take the wounded to different sites of medical care, where different personnel might deliver a variety of treatments. This chain of evacuation echoes the contemporary military medicine exhibition I had initially proposed. Interpreted through objects, images, text and film, it formed an illustrated timeline and a narrative spine for the Battlefield section of Wounded. This progressive physical journey away also evoked the passing of time – a progression which though ultimately linear could appear both inconsistent and contradictory. Where the first desperate half-mile on a stretcher through the mud of Flanders could well take longer than the 100 miles covered by an ambulance train delivering wounded to one of the French ports.

Visitors to the exhibition would have seen that the journeys of the First World War wounded usually went far beyond the French coast.[12] Once back home their journeys could effectively continue for decades as veterans progressively rehabilitated, adjusted, coped and lived on with the results of their wounds. This was implied by the structured narrative of Wounded, where the wounded themselves continued travelling through time and place away from the Western Front trenches. As they faded back into civilian life, others might be imagined as beginning their journeys from other battlefields in the century that followed. The exhibition’s coda continued the story right up to the present day as visitors encountered veterans who had recently served in Afghanistan and since been diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The message here was that a century on soldiers were still suffering the same kinds of wounds as their predecessors.

The young men in the trenches

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/010The young men queueing up to enlist in 1914 have the look of ghosts.

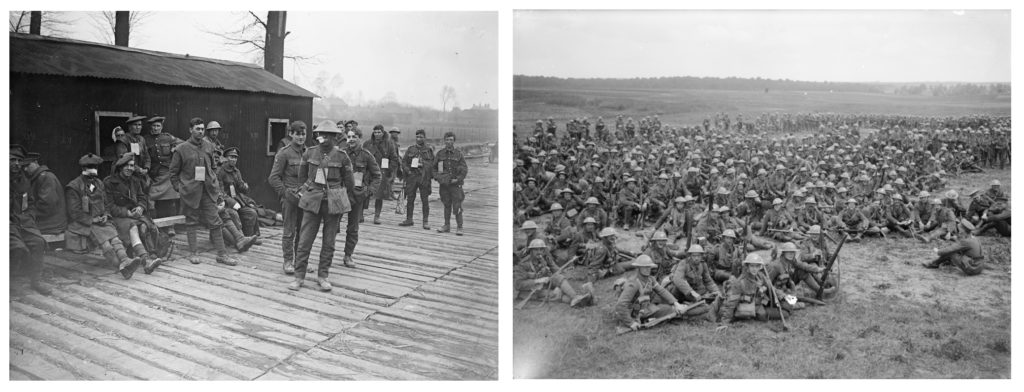

Beyond the theoretically measurable timespans encountered throughout the exhibition was something else time-related. This was how the very passage of time affects our perceptions of, and engagement with, the people so directly affected by the events of a century ago. Harry Patch, belatedly known as the ‘last fighting Tommy’ died in 2009. Wounded at the Battle of Passchendaele in 1917, he was the very last ex-British soldier who had fought on the Western Front. At 111 he became for a while the oldest person alive in the UK, but for quite a long time veterans of the First World War had inevitably been perceived as old men, and old men that were rapidly being consigned to history.[13] A sharp contrast to the time when they had epitomised one side of the maxim that “older men declare war, but it is the youth that must fight”.[14] The vast majority of those serving on the Western Front were under thirty, with a large proportion of those being teenagers, but as time moved on they had become men physically dissociated from the youthful vigour of their wartime service.

These youthful service lives had been recorded though, as unlike most previous conflicts the First World War was heavily documented in both photographs and film. Yet here too was a further time-linked distancing effect, another alienation device. In monochromatic silence, the participants in this four-year drama move jerkily around various stages in a world that seems as distant as the Charlie Chaplin films made in the same era. But the young men of 1914 are certainly still in there. Not long after Wounded closed, a visual reconnect with these long-dead players was breathtakingly realised in Peter Jackson’s film They Shall Not Grow Old. Here, digital technology re-interpreted the faces, characters and even the bloody wounds of the youthful men of the Western Front. The transition from scratchy and silent black and white to sound-filled colour provided a genuine ‘gasp-inducing moment’.[15] As Jackson himself tellingly stated, “They become real people. People that you recognise from work. People that you’ve been to school with.”[16]

Jackson’s manipulation of the original film footage has been criticised as well as lauded. In creating this retrospective version of reality did he actually commit an ‘act of barbarity, an unjustifiable marring of historical record for the sake of empty titillation’?[17] I would argue that while the introduction of the artifice of colour (as well as sound) also introduces a level of fiction, if convincingly done it can also create a degree of immersion that is harder to achieve with the black and white film imagery familiar to many of us. While a significant budget and a Hollywood director may be required to achieve that level of immersion, the use of colour at least was a consideration from the early stages of the Wounded project, and for not dissimilar reasons. Colour was seen as a potential means for helping to reconnect ‘us’ with ‘them’. Surprisingly, original colour images do exist of this war, with the autochrome colour process capturing many scenes from those times. Unfortunately, we found that these beautiful, rather dreamy images did not translate well when enlarged. They also feature almost exclusively French military personnel and associated theatres of war.[18]

Despite reservations, we did choose to use some black and white filmed sequences in the final exhibition. These were carried on two screens, one each in the ‘Battlefield’ and ‘Home’ sections. However, rather than a means to personalise the wounded the films were mainly employed to illustrate the mechanics and diversity of the archetypal chain of evacuation on one screen and give a sense of the types of rehabilitation and occupational health provided on the other. Elsewhere throughout Wounded, black and white still images were used to illustrate wartime sites and locations or various medical techniques and technologies. But when the wounded themselves and their carers did feature, particularly in the larger environmental graphics, we endeavoured to select contemporaneous images that at least suggested these were indeed Jackson’s ‘real people’.

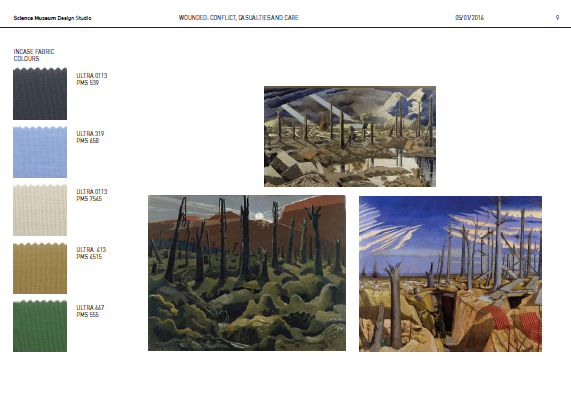

In the end we did include colour, but in a more abstract way. Based on the work of war artist Paul Nash, the Museum’s Design Office created a colour palette to delineate the different sections of the exhibition. This effect was further enhanced by varying the warmth of colour emitted by the gallery lighting. For example, the fabric of the ‘Battlefield’ section was characterised by a rather clinical sky blue, the ‘Home’ section by a cosier grassy green while the final ‘Wounded Today’ section mentioned above employed a pale sandy khaki, reminiscent of the environments being fought over in Afghanistan.

Ironically, it was in the interpretation of this final section, addressing more contemporary events, that we made our most forthright attempt to help visitors empathise with the wounded of the First World War. The content was created through a collaboration between the Museum, a group of British veterans from the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq who had been diagnosed with PTSD, and the military mental health charity Combat Stress – whose own origins lie in the legacy of the First World War. This very element could well have featured if my original proposal had been accepted. It presented a forum in which to highlight the hidden wounds of mental health as well as drawing out continuities and change between medical treatments employed on battlefields a century apart. But primarily, this section allowed us an opportunity to create an emotional bridge that might connect visitors with the wounded of a century ago. Alongside a small selection of objects and poems was a moving six-minute film in which the participants reflected on their experiences. These still young men are also revealed as the aforementioned ‘real people’, doing their best to get on with their lives. As one visitor succinctly commented on the film, “It gives the point of comparison. People still get hurt.”[19]

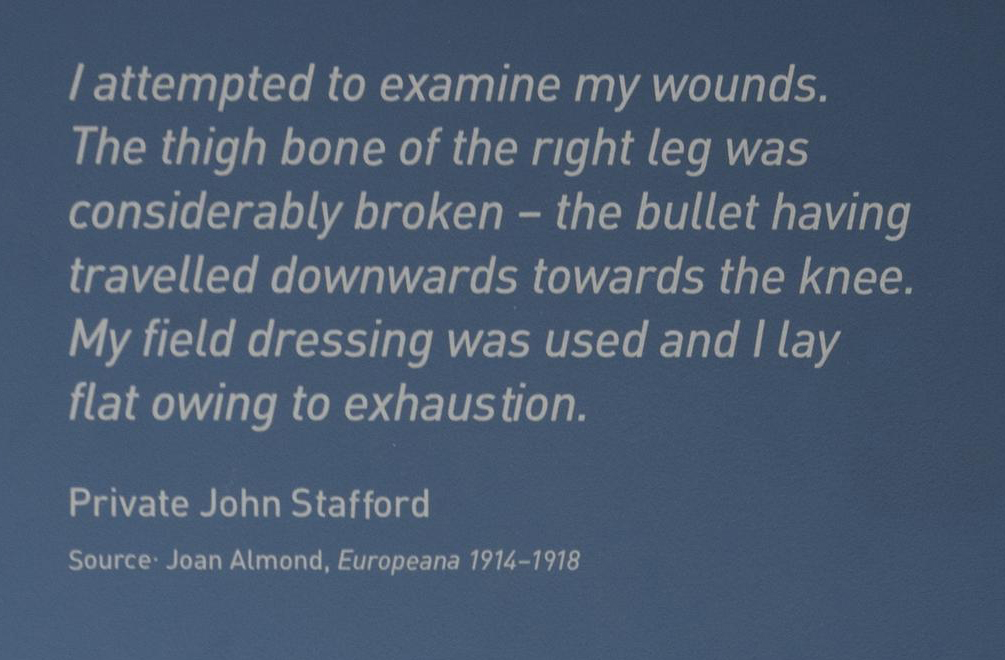

Unlike the veterans from Afghanistan, the recorded voices of those involved in the First World War were absent from Wounded. This decision was again largely influenced by considerations on the passage of time. While rich in detail, emotion and unique insight, and used to great effect by Peter Jackson, the recordings made by veterans wounded between 1914 and 1918 mostly feature older voices. These are the voices of men who many years later, perhaps unsurprisingly, often recalled the war differently to how they might have done in their youth (Taylor, 2013, pp 78–9). Rather than such extended reminiscence, we chose instead more contemporaneous voices via a number of short quotes taken mainly from journals or diary entries. These were reproduced on the back walls of display cases or alongside object labels.

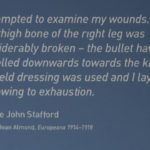

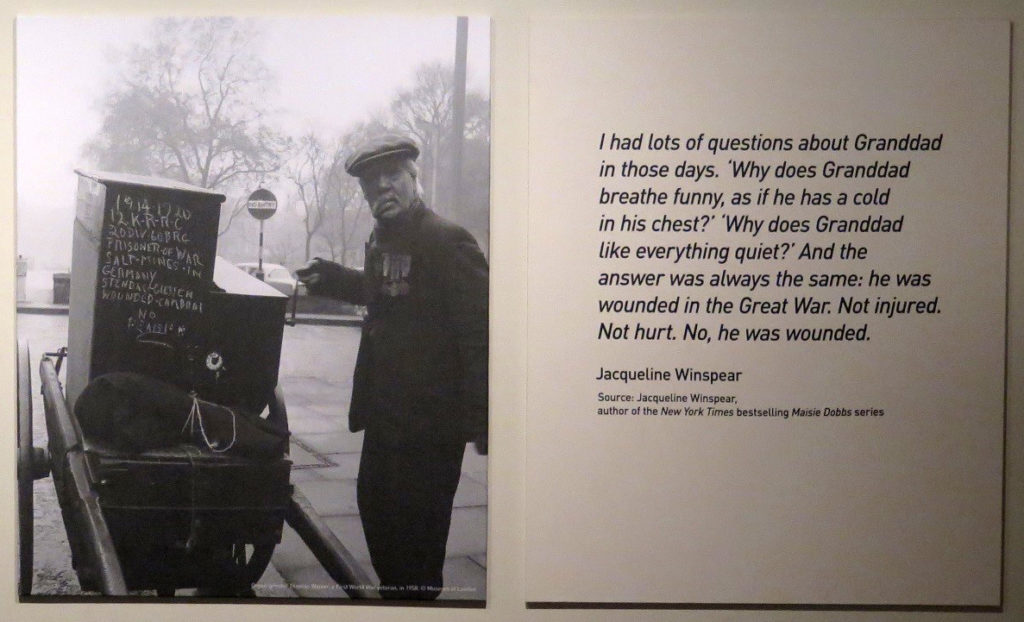

Had Wounded had more space and budget, the latter years of the lifelong journey of the wounded would ideally have been expanded upon. Regrettably, and rather ironically, older people were largely absent from the exhibition. But here I refer to older people in the right context – in the right time. There to reflect the everyday realities of long lives impacted by what might have been a fleeting event in their youth. One exception was the final image in the First World War sequence, which was displayed immediately adjacent to a quote. The quote was recent, from author Jacqueline Winspear recalling childhood memories of her veteran grandfather – mentally and physically wounded by the war – who in his seventies was still picking out artillery shell fragments from his skin.[20] It was a poignant nod to countless family anecdotes of ailing and troubled fathers and grandfathers whose war wounds were still impacting on new generations long after the event.

The image was taken in 1958 and I deliberately chose it for its ambiguity, for how it could be open to more than one interpretation. Does it show a be-medalled elderly man, disabled by his service and reduced to earning pennies as an organ grinder? Or had he always been a street entertainer who, like most of his generation, fought in the war; and who later chalked a reference to his wounding on a hand-cranked machine in the hope of bigger donations? Was the lop-sided droop of his face a result of that wounding or a more recent stroke, since many wounded veterans of course lived long lives in which such events could occur? Whatever the details, the image is drenched in time and was displayed to suggest a life, and thereby innumerable lives – however mundane, however tough – lived far beyond any ‘moment of wounding’, but which might still be lived with that moment’s long shadow.

Scale: individuals, the mass and the power of anonymity

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/011The worries, anxieties and traumas of the individual … were lost in the mass.

Chaplinesque or not, looking at the 1916 documentary/propaganda film The Battle of the Somme (sequences from which were shown in Wounded) one might agree with the author Samuel Hynes’ observation that ‘war is not a matter of individual voluntary acts, but of masses of men and materials, moving randomly through a dead, ruined world towards no identifiable objective’ (Hynes, 1992, p 125).

The sheer scale of the First World War retains the power to amaze and horrify. On the first day of the Battle of the Somme, British and empire forces suffered over 57,000 casualties – of which nearly 40,000 were wounded. By contrast, around the time that Wounded opened the number of casualties for British forces and associated civilian personnel in Afghanistan stood at 454 with around 2,000 wounded, after more than a decade of conflict. Such statistics mask the personal tragedies, but these two conflicts were extremely different in scale. And alongside such grim human statistics totted up between 1914 and 1918, there were also more prosaic reckonings – the 108 million bandages used across the British fronts, the 7,250 tons of cotton wool (van Bergen, 2009, p 286).

As curators we use objects to help us tell stories. As such, the more we know about an object, the greater the options are for storytelling. And if an object shows the marks and wear of use, is it not an even more powerful interpretive tool if we know who once held it? Perhaps a name, even a face, emerges from the historical research along with dates and circumstances through which to make even closer connections.

Such knowledge can create extra layers, the sprinkle of magic that can separate one object from a group that might otherwise be indistinguishable. But these objects are exceptional. Within the Science Museum’s collections, objects with direct associations with the First World War are numbered in the low thousands. Of that group only a very small number have a recorded link to a known individual. Given a reality where we could not reveal the biographical histories of individual objects, might the narrative focus of Wounded have been guided by individual personal stories instead?

In the earlier developmental stages of Wounded, I envisaged that the myriad experiences of British and empire soldiers wounded on the Western Front could perhaps be represented through detailing those of a handful of named participants. The visitor would be introduced to them and then follow their stories, from the moments they were wounded on the Western Front, through their frontline treatment and passage through the chain of evacuation, to their arrival back home for rehabilitation and a return to civil life. Representing the vast story through relaying the adventures of a small number of individuals has been a common interpretative approach taken by exhibitions marking the First World War centenary (Hicks, 2015, pp 88–97) and is a well-established means of tackling historical events, be they either traumatic or benign.[21] However, attempts to identify suitable candidates and then draw clear narrative arcs through the disparate timescales revealed both the research demands of such a comprehensive approach and, for us, its limitations as a means of storytelling within the context of this exhibition.

Where they exist in the historic record, the experiences of the wounded have largely been written as episodes within broader narratives, whether military, medical or socio-historical. It could be in the anecdotal details of a specific battlefield wounding, the background to a recorded clinical intervention or in the descriptions of rehabilitation that names and faces are most often revealed. These relatively brief moments of sharp focus that appear in written accounts might have been used in the exhibition to contextual a particular wound type or medical treatment. Yet filling out the blank spaces of time and experience either side of these snapshots in order to reveal a more complete personal journey were not the remit of the original narratives, and seeking that information would have required levels of research considered impractical for this project.

This was an approach that could have been effectively applied to my original contemporary conflict-centred proposal where our involvements have been relatively small scale and the wounded personnel who might have featured would still be alive and still undergoing rehabilitation. With Wounded, I was initially concerned that a decision not to highlight this kind of individuality could weaken the interpretation. For example, would the series of contemporaneous quotes which punctuated the exhibition have been more powerful if accompanied with an image of the individual being quoted? Yet a lack of contemporaneous images for some and a lack of any image for others would have brought an undesirable inconsistency to the approach taken in Wounded.

Instead, I came to feel that there could be an interpretive strength in a display where individual faces remained largely un-named and names, where they appeared, being largely ‘un-faced’. That there was a power in a high degree of anonymity as it could act as a reflection on the sheer inhuman scale of the conflict. Names and faces were by no means absent from the exhibition, but in the final version the two were generally not connected. An obvious exception to this approach would initially appear to have been the veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq who collaborated with us to produce most of the final section of the exhibition. But even here, while we have faces and voices in the accompanying film and labelling we only have the first names of the participants. This was their collective choice, but as it turned out it was very much in keeping with the rest of the exhibition. To virtually all our visitors, they too were anonymous – they too were rendered as ‘everymen’.

There were specific exceptions. One wounded individual who was both pictured and named was Sergeant Sawyer Spence. On the Western Front in August 1918, Spence’s uniform became contaminated with mustard gas as he lay in a shell hole. By the time he had reached a hospital back in England his body was covered in suppurating blisters and he was recorded as one of the worst cases ever seen in this country. The decision to identify him was partly taken for pragmatic reasons. The original images were reproduced by permission of Spence’s proud grandson, who has actively publicised his grandfather’s ordeal. But as probably the most shocking image of a wounded individual within the exhibition,[22] where Spence’s beleaguered eyes directly engage with the viewer, a more personal story was revealed. In the course of hosting tours of Wounded, it was noted that visitors who enquired about him felt some reassurance in knowing he had survived his ordeal.

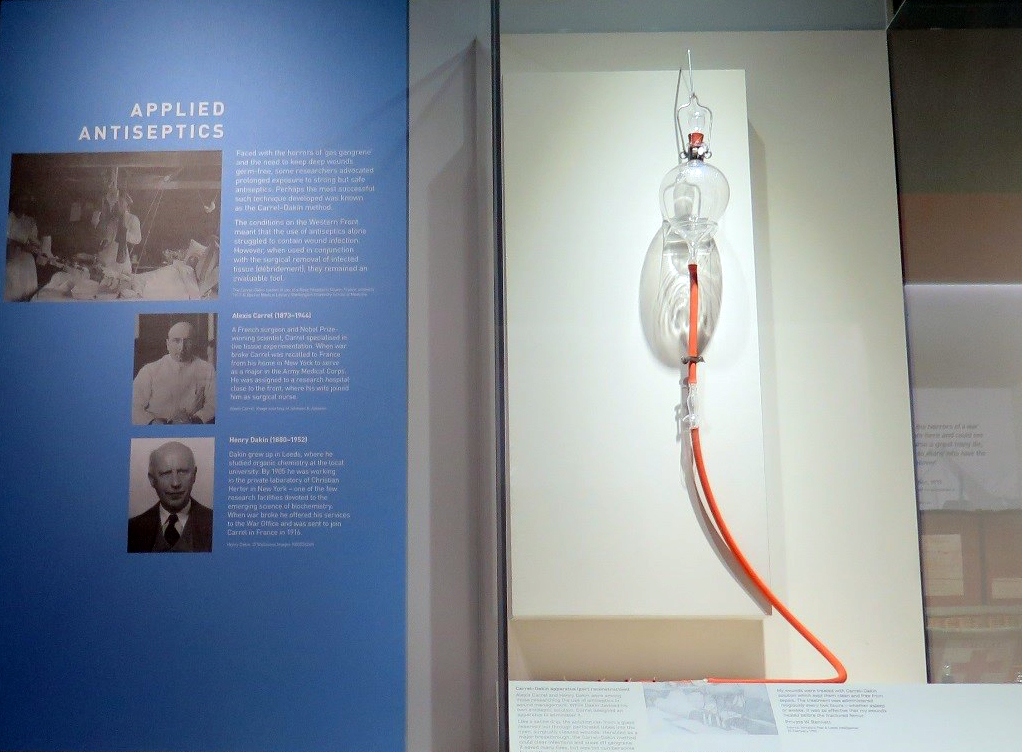

Visitors also found a further breach in the general approach to anonymity. When content was focused on specific innovations in medical or rehabilitative techniques and technologies or on specialist centres of care – be they on the battlefield or at home – individuals were both named and pictured. But these innovations were intended to form a distinct thematic thread within the larger story of wounding on the Western Front. The subjects were not ‘the wounded’ but the scientists trying to assist them. Here visitors could recognise the individuality of the innovator and the innovation, which was subsequently manufactured or delivered en masse to ranks of anonymous soldiers.

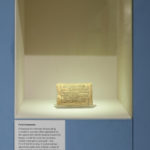

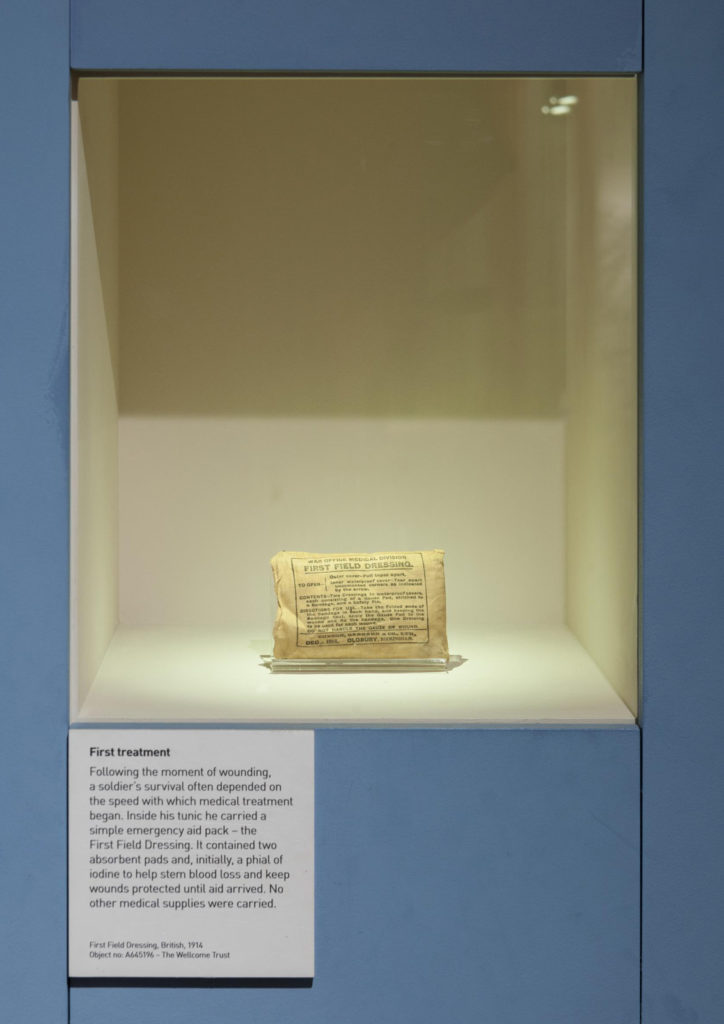

Beyond these underlined innovations, the remaining objects on display were also largely anonymous, in that any personal associations were generally unrecorded. Inevitably the practicalities of display meant that while they had mostly been produced in huge volumes, in Wounded they were usually shown at the other extreme of scale – as single representatives of their kind. A first field dressing, displayed in isolation in its own small case, was representative of the one carried by each soldier on active service. For those wounded on the battlefield, they would often be applied as an initial treatment. Here the very anonymity of such a mass-produced object mirrored the anonymous men who each carried them, their individuality lost within the mass armies receiving mass casualties on a daily basis, month after month, year on year.

The anonymous made tangible

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/012In the exhibition as on the battlefield, the individual soldier was almost entirely lost within the vast scale of the trauma. And yet a sense of those long lost could be evoked by the objects themselves. A significant number of those chosen for display in Wounded had very clearly been heavily used – and abused – with their surfaces scuffed and scratched or contents part-removed, re-arranged or added to by unknown hands, the distant participants still implied in the general wear, tear, adaptations and markings.

Within a context as overwhelming as the First World War I would argue that such objects could impart a particularly powerful message, the lost physical connections expressing a greater poignancy. A sense of humanity conjured from objects that still retain ‘ghostly traces and memories’ to each become ‘a memento of the passing of time’.[23] Personnel who were unknown to Museum visitors but whose presence, when tangibly evoked through such objects, might allow our visitors a closer connection with those involved in their millions in the mass enterprise on the Western Front.

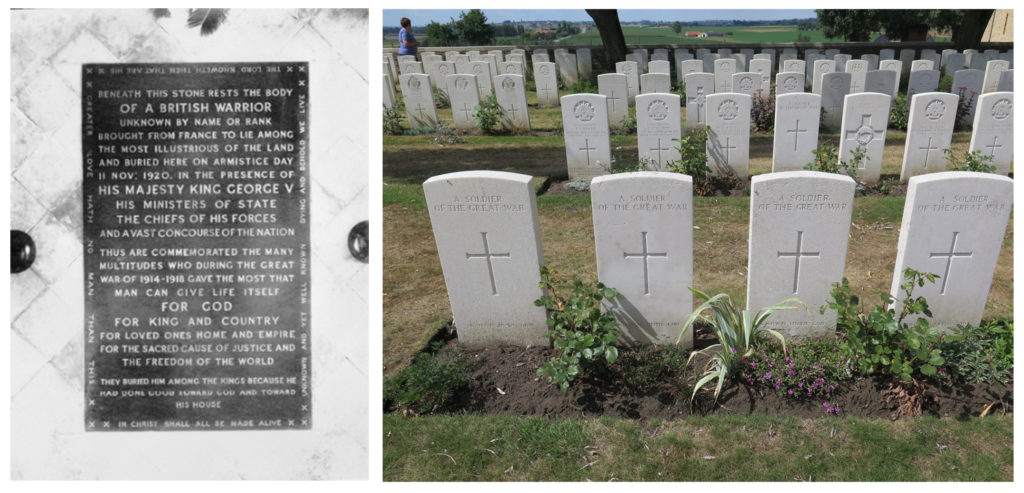

In the public remembrance of this war, anonymity has actually been central. The decision to dedicate a tomb in Westminster Abbey to an unknown warrior was a deliberate acknowledgement of a public need; and for those whose loved one’s body had never been found the site had a particular power. The remains could theoretically be their lost son, father, friend or husband.

This tomb of the ‘everyman’ became a focal point both for mass national mourning and very individual grief. As did the Cenotaph[24] memorial in Whitehall. That was originally envisaged as a temporary structure, but so captured the public’s imagination that it was rendered permanent in stone. On to this ‘blank public space, millions of men and women could project their only private feelings’ (Reynolds, 2013, pp 175–76). A century on, visitors walking past the awe-inspiring rows of white Portland headstones in the cemeteries around the old Western Front may receive an added emotional punch from the many marked simply ‘A soldier of the Great War – Known unto God’.[25] Anonymity can reflect both ends of the ‘scale’; an individual – the ‘everyman’ – but one who is subsumed and lost within the mass.

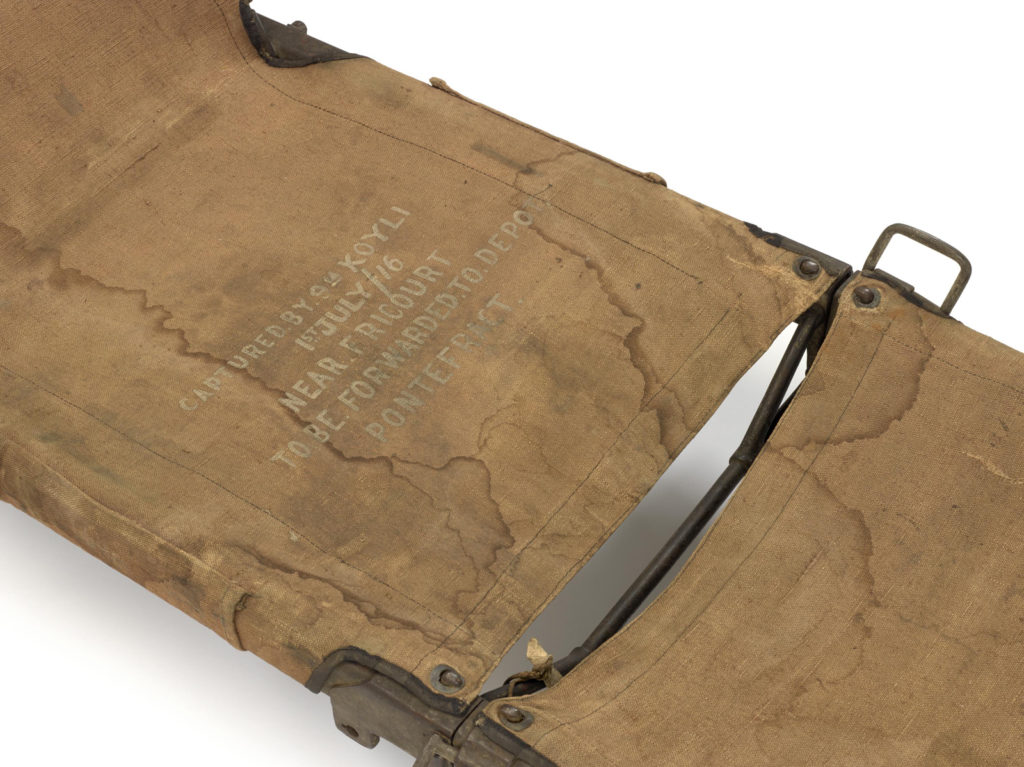

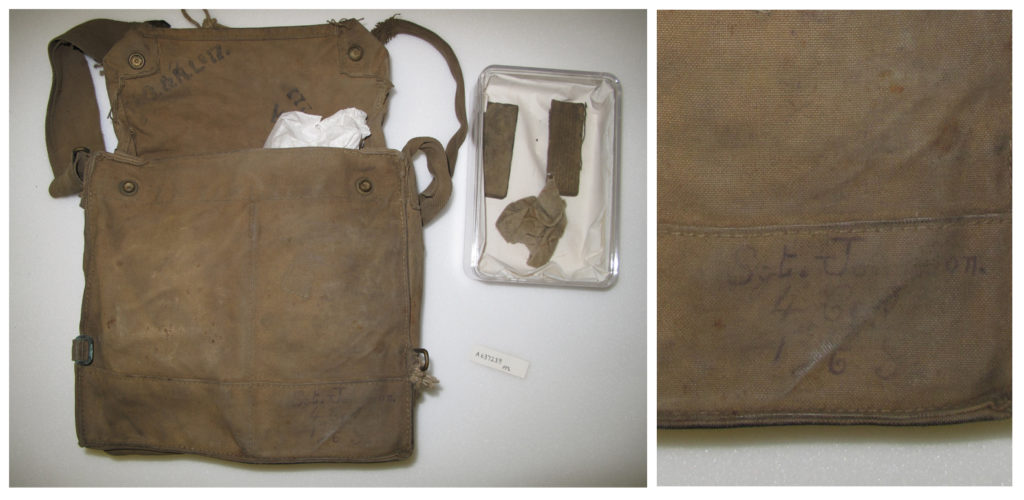

In Wounded, it was decided not to draw attention to the identities of some of those that we could actually associate with particular objects. For example, the nurse who wore the pinafore displayed and the officer whose name is clearly visible on a gas mask haversack. In the context of this exhibition, where they are representing figures from the massed ranks, those additional details were not needed. One of the over-arching messages of Wounded was that the First World War was a war of tremendous scales, of both resources and personnel, and this of course included the numbers of wounded. In this context and with these objects, biographical information seemed superfluous – a case where instead of ‘putting the burden on the visitor to take in too much information, more can be accomplished by leaving things unsaid’ (Wood and Latham, 2013, pp 146–47).

The handwritten name on the worn haversack providing the ghostly evidence and poignant reminder that it belonged to somebody – another everyman. On one level the haversack was there as the standard issue carrier for the adjacently displayed mask; one that showed an improved technological response to the dangers of poison gas. But look closer and its scuffed grubbiness and the scrawled name at least suggested connections beyond the purely functional. I feel such qualities can touch on what Roland Barthes has referred to as inherent ‘other things’, where some objects can suggest ‘something else’ which evokes a ‘meaning which overflows the object’s use’ (Barthes, 1988, p 182).

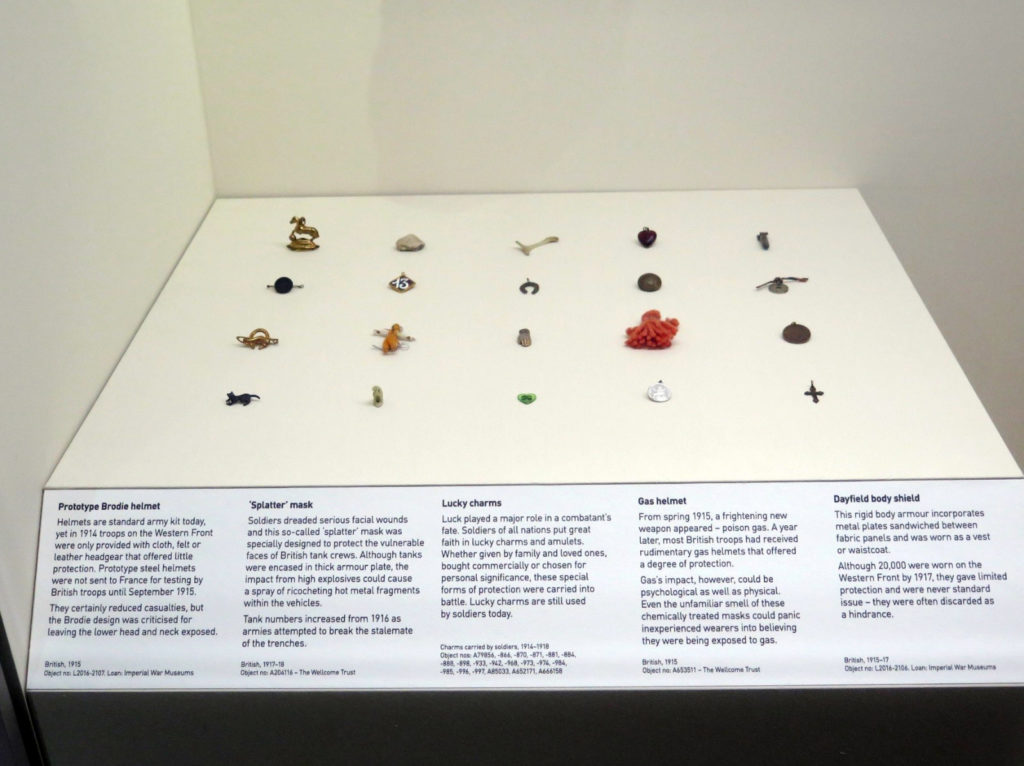

Perhaps the most personal of the ‘anonymous objects’ were displayed in the introductory section of the exhibition. These were twenty lucky charms, carried for protection by soldiers during the war, shown within a case that looked at the vulnerability of the human body in the face of the Western Front’s weaponry. They included everyday items like buttons and coins as well as handmade dolls and animals and were displayed in ranks, almost as if on parade. As a group they were objects that referenced back to the anonymising nature of the First World War, but here was also an opportunity to evoke individuality within the masses through the very uniqueness of each of the charms. Who carried them, let alone whether they were the parting gifts of wives, mothers, children or lovers we will almost certainly never know. But we hoped that that very unknowing would create a particular aura. They stood as objects for which visitors might collectively imagine thousands of different owners, with thousands of individual stories – “the little human things, which brought the men to life”.[26]

The phantom traces left by unknown users were often key reasons behind particular object selections. The aforementioned haversack was chosen above others because of the hand-written name – even though that wasn’t explored further. And in several cases, more complete but essentially unused ‘warehouse fresh’ objects in our collections were rejected in favour of the used and begrimed.

One such object was described as ‘Colt’s stretcher for narrow trenches’. The Science Museum has two examples of this wartime design. It had been developed in response to problems encountered when manoeuvring standard stretchers within the confines of winding, narrow frontline trenches. One of our examples had previously been displayed for several decades in the Museum’s main Medical Galleries. In good condition, it is clearly the actual stretcher shown in the article published in The Lancet in 1916 that first announced the invention (Holt, 1916, pp 202–07). However, for Wounded the other example was chosen. In far worse condition and requiring significantly more conservation work, this was an object with the clear patina of use. It also showed signs of being adapted by its users, for example in the crudely attached additional padding for the bearers who would have supported this unusual stretcher on their shoulders. Such modifications supported the background information we had which suggested that of the two, this was the one that had actually seen action at the Front.

This object was an innovative variation on what was both a standard piece of mass-produced equipment and a vivid symbol of wounding itself. Suspended from a case ceiling, the technological aspects were clear, but something more was brought to the display through its condition and appearance. Anonymous hands had modified this particular stretcher to suit the practical realities encountered when carrying the wounded and this personalisation imbued the object with qualities that the more pristine version was lacking.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201313/013And all the wounded were wounded for life.[27]

From my personal perspective, the character of the Wounded exhibition bore both strong similarities and distinct differences to the original exhibition proposal that I had first envisaged a decade ago. That initial concept was the blueprint which I later tried to adapt when creating a narrative set a century earlier and on an infinitely vaster scale. During a project meeting I once described the outline of the earlier exhibition as a long journey with time traced out like ripples across a pond made by a single, stone-dropping moment – the ‘moment of wounding’. The time ripples being accompanied by encounters with medical personnel and the treatments they would apply and linked with the physical movement away from that point of wounding. Referring back to this essentially linear structure when developing an exhibition based in the sprawling complexity of the First World War revealed both challenges and drawbacks, but I also believe generated intriguing opportunities for content interpretation.

Inevitably many factors shape a final exhibition. Aside from more mundane influences such as display space and budgetary restrictions, in Wounded other significant factors included the character and content of our extensive but eclectic First World War holdings as well as the decision to link it to the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, within the broader commemoration of the whole war. But I have wondered what the final exhibition would have looked like if it had started from a blank canvas, rather than having had a prototype version in the background. That original proposal had developed no further than a basic outline concept, but elements of it persisted to an unexpected extent to fundamentally guide much of the structure and character of the final exhibition, creating – I believe – a complex layering of ideas and meanings which gave Wounded a particular richness and depth.

In its realised version, Wounded tried to convey a far more messy and ambiguous reality than I believe an exhibition on contemporary military medicine would have done, while retaining a structure and given strength and meaning by an under-pinning that was linked to the original idea of ripple-like time progressions. This characteristic was there from the beginning, but continued to manifest itself as the project progressed – sometimes in unexpected ways. The passage of time was implied in different guises, be it in conventional minutes, days or years or communicated via youthful faces or in the marks of physical wear left on objects. And just as contemporaneous quotes and imagery were a key part of the final exhibition – be they from 1916 or the early decades of the twenty-first century – contemporaneous writings also helped to guide our final object selections.

The final exhibition also threw up the challenges of what I have referred to throughout this paper as ‘scale’. Moving from the setting of twenty-first-century Iraq or Afghanistan to the Western Front a century earlier imposed limitations on, and I feel also weakened the case for, an exhibition focused on identified wounded individuals and their personal stories. Instead, objects, words and imagery that could evoke individuality, but individuality anonymised by the sheer scale of the 1914–1918 war, felt like a powerful means to evoke the people at the centre of this mass trauma.

From a medical perspective, Wounded outlined some of the key forms of treatment and care. But here too the exhibition’s approach was primarily to emphasise how these techniques, technologies and strategies were applied on a mass scale and only very rarely used as an opportunity to highlight specific cases from among the overwhelming volume of casualties. Our collections allowed us to draw out episodes from this complex medical story, and innovations and advances were central to these, but the material culture also proved rich enough to present a more nuanced and less triumphalist reading of how British medical practice coped during the First World War and the years that followed.

As the curator who worked on this exhibition from its very beginnings until its fruition, there is one final object that for me encapsulates all the qualities that have been discussed in the previous pages. The object is an artificial leg, whose owner was recalled in the layers of almost obsessive repair work that had been applied over a long period of time. Such clear evidence of use also touchingly suggests the passing of time in an onward journey towards old age. It evokes a former user who now, as then, is lost in the anonymous masses that epitomised that war. The leg is part of the large collection of limbs acquired from Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, an institution whose origins lie in the First World War[28] and is another object offering itself up to more than one interpretation.

British army and navy amputees had been entitled to free artificial limbs since Napoleonic times. These were government-issue prosthetic limbs, of reasonable quality and of a type ‘deemed likely to be most useful to them in the everyday life of their class’ (Heather Bigg, 1885, pp 101–02). They were often a vital means to get back into employment, but in an era before the Welfare State, many First World War veterans feared losing their jobs should they need time off to get their limb repaired (Guedalla, 1919, p 9). They might be reluctant to take the risk, deciding to patch up their existing prosthesis instead. Another explanation for this striking leg could lie in the wearer’s desire not to jeopardise what they found to be a comfortable fit. For many amputees, then as now, comfort has usually outweighed aesthetics[29] and this wearer may have resorted to home repairs to extend the life of their prosthesis. There are a number in the Museum’s collections which carry such evidence. We don’t know the reason behind this example, but in the context of the exhibition it felt as though this lack of knowing really didn’t matter. Fundamentally, it is the lasting physical evidence of a wounding received in the First World War and of an unknown amputee, issued with a once pristine new metal limb, fading back into civilian life. One time-marked with progressive repairs as he lived on, still dealing with the impacts of a very personal but increasingly distant moment of wounding.

Tags

Footnotes

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. Back to text

Back to text