Embedding plurality: exploring participatory practice in the development of a new permanent gallery

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305

Abstract

Increasing numbers of museums and galleries worldwide have developed an array of working practices that might be termed ‘participatory’ or ‘co-creative’, which seek to involve visitors, non-visitors, community and interest groups with diverse forms of expertise and perspective in their activities. Frequently the central aim of such practices has been to strengthen relationships between a museum and its audiences through projects that are jointly conceived and developed with local communities. However, relatively little attention has been given to participatory practice within the work of larger institutions, particularly those with a national and international remit, reach and audience base, where participatory practices are adopted to enrich the development and content of new permanent displays (aimed at large and diverse audiences). Drawing on a single case study – the development of the permanent Information Age gallery at the Science Museum in London, which opened in 2014 – this paper aims to reflect upon the extent to which existing concepts, theories and approaches to participation and co-creation resonate with museum work of this kind.

Unlike many participatory practices internationally, the range of projects and activities utilised in the development of Information Age were driven less by a desire to share authority and decision-making with communities outside the museum and more by a concern to foster involvement with diverse communities of interest in the making of a major gallery and to generate and embed plural perspectives on the objects and stories presented within it. This paper raises further questions around how participatory work is perceived, valued and shared across the sector.

Keywords

co-creation, co-curation, Information Age, museums, participation, participatory, Science Museum

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/In the last decade, increasing numbers of museums and galleries worldwide have developed an array of working practices that might be termed ‘participatory’ or ‘co-creative’, which seek to involve visitors, non-visitors, community and interest groups with diverse forms of expertise and perspective in their activities (Simon, 2010; Lynch, 2011). Such practices are found in all kinds of museums, large and small, and those with both local and national reach. Frequently the aim of such practices has been to strengthen relationships between a museum and its local audiences, and a growing literature has developed, critiquing, evaluating and reflecting upon the different approaches organisations have taken (Lynch and Alberti, 2010; Spence et al., 2013; Gibson and Kindon, 2013). However, relatively little attention has been given to participatory practice within larger institutions, particularly those with a national and international remit, reach and audience base. What forms might participatory practice take within such organisations? What opportunities and challenges are posed by the use of participatory approaches where the end result, proscribed and pre-determined by the museum, is a major permanent gallery intended to engage and meet the needs not only of those who participated in its production but of wider audiences, including diverse local, national and international visitors? This paper explores these questions in the light of the lively debates that surround participatory practices in the international museum sector. Drawing on a single case study – the development of the newly opened Information Age gallery at the Science Museum in London – this paper aims to reflect upon the extent to which existing ideas, theories, and approaches to this type of work resonate with museum work on this scale. The development of the Information Age gallery saw a shift away from small-scale, temporary exhibition-driven or project-led participation towards participation which aimed to significantly impact upon the core offer of the museum: its permanent galleries. Both in scale and ambition, the participation activities that shaped Information Age sought to go further in terms of co-operation across departments to embed community involvement more fully in the exhibition development process than had been attempted previously at the Science Museum.

This paper developed out of a collaborative research project undertaken in 2014–15 by the Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG) at the School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester, UK, together with audience researchers at the Science Museum. The Leicester research team surveyed recent models of participatory and co-creative practice across major institutions worldwide in order to understand the state of the field and the range of terms used to describe such work. This drew out current thinking and practice for the Science Museum at a critical point in its work with audiences and communities of interest. Holding the practices of the Science Museum’s participation work up to existing theories, models and debate prompted a consideration of how the approach taken with Information Age – shaped by the institution and focused around the pre-determined end goal of a new gallery rather than the more open-ended and community focused participatory practice that has received most attention within the sector – might be assessed and understood.

The research also elicited thought about how the field might better integrate participation in ways which continue to serve a broad range of stakeholders and a diverse visitor base. Responding, in particular, to Govier’s call to explore participatory practice not only as a route to sharing authority with communities – an important theme within current participation discourses (Govier, 2010; Flinn and Sexton, 2013) – this paper suggests that approaching participation more holistically and embracing its many forms can transform the ways in which museums interpret collections and open up ways of enriching practice across the institution.

The Information Age gallery

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/002Information Age is a new permanent gallery at the Science Museum, London that opened in October 2014. It tells the story of how information and communication technologies have transformed our lives over the last two hundred years. Through a display of over eight hundred unique objects this 2500m2 gallery seeks to expose, examine and celebrate the technology that has changed the way we connect with one another and to illuminate how human creativity has defined and shaped our information and communications networks.

There are six zones in the gallery, each representing a different technology network: The Cable, The Telephone Exchange, Broadcast, The Constellation, The Cell, and The Web. The gallery explores the important events that shaped the development of these networks, from the growth of the worldwide telegraph network in the nineteenth century, to the influence of mobile phones on our lives today. Parallel stories of the past, present and future of communications technologies are told through the eyes of those who invented, operated, and were affected by each new wave of technology.[1]

Information Age combines showcase displays, innovative digital interpretation and immersive environments and has a dedicated workshop space and accompanying learning programme. The gallery targets families with children aged 11 years and over, independent adult non-science specialists and school pupils and their teachers. Within these target audiences and in line with the Museum’s Audience Development Plan (Science Museum, 2015), the gallery is also intended to appeal to new visitors from black and minority ethnic and lower socio-economic backgrounds, as well as visitors with disabilities.

Participation activities on the Information Age gallery development drew upon a long history of participation and audience engagement initiatives at the Science Museum. In various ways and across different kinds of projects, audiences have been invited to collaborate with staff over a number of years. For example, audience-led events to engage under-represented groups in contemporary science debate at the Museum’s Dana Centre; a collaborative project with transgender youth leading to a co-created display case within the Who Am I? gallery; the involvement of audience groups to co-curate the Oramics to Electronica exhibition; and co-creation experiments in various temporary exhibitions on current science issues in the Antenna area of the Museum [2].

Building on these predominantly smaller-scale initiatives, which had resulted in largely temporary outputs, the Information Age gallery was an opportunity to extend and further embed the use of participatory practices in the development of a major new permanent gallery, an approach that tested the institution’s understanding of the role, purpose and place of collaboratively produced outputs.

Inspiration was taken from other large-scale permanent redevelopments, such as the community-centred Riverside Museum in Glasgow, which gave Science Museum staff the confidence to explore ways of embedding user stories into its own interpretation on a larger scale than it had previously attempted.

The decision to use participatory methods in the development of the Information Age gallery was given additional impetus by the Museum’s concern to develop galleries that could appeal to more diverse audiences. The Museum saw an opportunity to foster greater inclusivity and to reach out to new, currently under-represented audiences, by inviting specific groups to research, plan and create with the Museum. The theme of user-driven innovation and development was central to Information Age and naturally converged with the desire to include a diversity of voices (including those of the visitor) in the gallery’s narrative. This meant that there was an obvious synergy between the gallery’s aims to showcase the voice of the users – the people who felt the influence of communication technology – and the Museum’s ambitions to extend participation practice. With this in mind the principal objective for Information Age was to create, through the process of participation, high quality and nuanced experiences for visitors who would encounter the participation project outputs in the gallery. In this way, the main driver for the participatory practice within the gallery was not sharing of authority with communities per se but rather the enhancement of the experience for future visitors to the gallery that would be produced by participatory methods. It was hoped that visitors to Information Age, who encountered a gallery shaped by collaborative means, might find greater relevance to their lives, and stories they could relate to more readily.

Another feature of Information Age was that unlike the Museum’s other participation projects, which tended to originate in the Learning or Contemporary Science departments, a cross-disciplinary exhibition team including engagement, curatorial, content development, evaluation and new media staff took on responsibility for delivering these initiatives. From the beginning, the entire cross-disciplinary team was supported and trained not only in how to work in a more participatory way (often in unfamiliar ways and with audiences they had no prior experience of engaging), but also in understanding why this could be a beneficial way of working, how it would benefit their own practice and what the impact and outcomes were.

It quickly became clear that in order to foster a shared understanding of the goals of participation among the staff, a consistent and clear language was needed. To date, collaborative work with the public at the Science Museum had already been termed in various ways, but with the huge variety of experience and expertise across the Information Age team, the need for clarity in language and meaning was brought into sharp relief, and understanding how notions of ‘participation’ were commonly applied in the sector, and how they were to be applied at the Science Museum, became an important task.

Exploring 'participation' concepts and terminology

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/003The term ‘participation’ is widely used in museums across many parts of the world, but has significantly different meanings in different contexts. In the UK, for example, ‘participation’ can sometimes be used simply to refer to attendance, the act of visiting a museum or going to the theatre.[3] Meanwhile, terms like ‘co-production’, ‘co-creation’ and ‘co-curation’ are used at various times to denote collaboration between museum staff and a variety of stakeholders – community groups, visitors and non-visitors, special interest groups, individuals with specialist professional and academic expertise and so on. A burgeoning literature reflecting on the challenges and opportunities afforded by a closer working relationship with different constituencies and stakeholders has generated further terms which are frequently imprecisely defined and used in a variety of ways: for example, in addition to ‘participation’, ‘co-creation’ and ‘co-curation’, there is ‘public-curation’, ‘community collaboration’, and ‘co-production’. The sheer breadth of terms applied to these practices, while sometimes subtly nuanced in meaning, can nevertheless hinder constructive dialogue around the purpose and progression of such work.

In the context of working with non-professionals in museum projects, Bernadette Lynch has written that ‘words matter’: the need for both museum staff and audiences to understand the goals and intended outcomes of participatory work, beyond the rhetoric of ‘shared authority’ or ‘co-production’, is shown to be critical in avoiding disillusionment of the communities involved (Lynch, 2011, p 16). Crucially, this need for clarity applies to internal conversations too, particularly where – as with the Information Age – a concern to facilitate participation is shared by multiple members of the exhibition development team and not driven by a single department. The breadth of activities on the gallery development necessitated a clear articulation of the underpinning assumptions and meanings of participation that could incorporate content development at all stages of the gallery’s lifespan, from pre-opening through to post-opening and future gallery revisions (Science Museum, n.d. a). It needed to fold together different forms of participation: online and on-site; work with gallery visitors and wider audiences. However, the existing literature was largely found to maintain boundaries between different kinds of community involvement, often speaking primarily to issues around the participation process and focusing on either the impact of projects on participants or the final output experienced by visitors, but rarely both.

Participatory projects and experiences

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/004Many participatory activities are focused on individual projects. In the UK many of these have been supported with funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, which has made ‘participation’ a key requirement for support, defined on the basis of widening audiences and creating opportunities for engagement. To be eligible for support, projects must ‘help more people, and a wider range of people, to take an active part in and make decisions about heritage’ (Heritage Lottery Fund, n.d., 19). ‘Community participation’ is understood as ‘people having an active role in your project, in particular taking part in decision-making and delivery’. Where the Heritage Lottery Fund guides organisations to support participants with ‘their own plans’, there is an emphasis on ‘projects’ for which the community takes ‘responsibility’ (Heritage Lottery Fund, n.d., 18). The language used to describe the community’s active rather than passive role is largely aligned to the language of project management and product design rather than embedded practices.

Meanwhile, the value of outputs and outcomes that are pre-determined by the museum and projects that are driven by the institution rather than the community have been called into question. In her writing on participation, Simon evokes a language that prioritises experiences rather than projects, and she threads this through discussions of both the design and consumption of experiences, emphasising the need to support different levels of individual and social meaning-making (Simon, 2010, p ii). For Simon, participation (in the specific project sense above) is one of many possible design strategies that an institution can use to create personalised, relevant, fluid, creative and social experiences for visitors (2010, p iv). Simon’s framework helpfully acknowledges the value of both institutionally defined, output-centred projects as well as more open-ended activities that emphasise creativity and process. Yet some have reported that the process of participatory projects can be potentially more significant than the final product – the display, text, resource or other tangible output. This was the case for the innovative Manchester Museum exhibition Myths about Race, described by Lynch and Alberti (2010), and for the Museum of London Docklands’ Sugar and Slavery exhibition (Spence et al., 2013). Here, the process of reaching out to and empowering participants trumped the significance of any final ‘product’ created. Where the primary goal is ‘power-handover’ – a fundamental shift in museum practice intended to empower communities to have a much greater say in the work that museums do – this emphasis on process is clearly appropriate and, indeed, necessary. But this conceptual underpinning, which places process over product, poses questions for contexts where the quality of both the participation process and the final product are paramount.

As is evident from Simon’s writing, the development of social digital platforms and participatory culture more widely have influenced long-running discourses around working with communities to create museum content and experiences (Simon, 2010). While differently situated, research and practice across both digital and non-digital fields comment on remarkably similar issues. They each centre on a set of questions around what makes participatory work genuinely participatory, meaningful, and impactful for both museums and participants. Writers question the quality, value, and impact of participation, not only on museums and participants involved, but increasingly on wider visitors who encounter the products that result from participatory projects (Allen-Greil and MacArthur, 2010). Is the project genuinely participatory and dialogic (for example, Macdonald cited in Atkinson, 2010; Lynch and Alberti, 2010)?; Do participants really wield significant power in shaping the museum’s interpretations (Lynch and Alberti, 2010; Lynch, 2011; Smith, 2012)? Are museums learning enough from other sectors who are developing participatory experiences with high-quality outputs (Carpentier 2011; Kidd 2014)?

While there remain different sets of literature spanning exhibition development, digital media, and community engagement, which explore different types and purposes of participation – from community empowerment to visitor agency – there are recent attempts to conceptually draw together this breadth of practice and provision. Thinking beyond a ‘tacked-on’ activity – usually the responsibility of learning, engagement or audience-focused staff – the notion of participation has been explored more holistically in the literature. Stanhope and Poole (2012), for example, suggest that the sector might more nimbly thread together skills in ‘engagement, collections and digitisation into a single stream of collaborative participation and learning’. Similarly, Satwicz and Morrissey discuss what they call ‘public curation’, which is defined as:

[…] an umbrella term to encompass “participatory design,” “user-driven content,” and the broad and creative ways public (or non-professional) audiences are increasingly and collaboratively involved in shaping museum products (e.g., exhibitions, web sites, archives, programs, media), processes (e.g., design, evaluation, research, public discourse), and experiences.

Such a holistic view includes but goes beyond the realm of delineated projects to include the breadth of museum processes and experiences. It can tie together both digital and non-digital audience participation to acknowledge and draw strength from the fact that these are working towards the same goals of supporting engagement and meaningful experience. Other underpinning ideas, particularly the notion of sharing power and decision-making with audiences, raises issues that warrant further critical examination, especially in the context of participation that is undertaken with a primary aim (as with the Information Age project) of enriching the interpretation and visitor experience within a major permanent gallery.

Shared authority and shifting notions of expertise

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/005Although described in multiple ways, a key value ascribed to participatory work in much of the literature is the shift in power from ‘experts’ to ‘non-experts’ that enables museums to foreground new and diverse voices. Indeed, much writing in this area concerns the implications of participatory work for the role of experts (see, for example, Stein, 2012). Kathleen McLean notes that while most museums incorporate participatory activities at some level, such as inviting comments and make-and-take activities, these ‘mostly preserve the usual novice-expert construct: the museum pushes content toward the visitor and the visitor reacts’ (McLean, 2011). This problematisation of the ‘expert’ voice, however, has prompted challenges to the way the terms ‘expert’ and ‘non-expert’ are often used. The use of such terms to frame conversations about participation in museums can work to reinforce hierarchical approaches to knowledge about collections, where professional knowledge is sometimes considered a more valid form of expertise than that which derives from, for example, lived experience. To tackle this, Dodd, Jones and Sandell, in their work to develop new narratives around disability in museum displays, have used the concept of the ‘trading zone’ to shape a process through which different forms of expertise (including that which derives from personal experience of impairment and disability) are accepted as equally valuable in relation to collections (Dodd, Jones and Sandell, in press). These experiments suggest possibilities for more inclusive frameworks for understanding expertise and how museum knowledge about collections is produced, validated and shared.

This problematisation of the expert voice has also encouraged different forms of participation to be considered hierarchically. Onciul notes that research into community engagement and co-production of knowledge in museums has often been approached using hierarchical models of participation, such as that presented by Sherry Arnstein (Onciul, 2013, p 82). Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation (1969), which sees a hierarchical scale from non-participation to tokenism to citizen power, has been used to theorise degrees of control in participation in museum contexts. In this model, citizen power is defined by ‘partnership’, ‘delegated power’ and full ‘citizen control’ (Govier, 2010; Gibson and Kindon, 2013).

The notion of a hierarchy of varying levels of participation has strongly influenced debate and practice within museums. The process of ‘consulting’ with audiences has been understood as low down on the spectrum of meaningful participation, where audiences are asked to contribute to museum knowledge or advise on outputs in a one-way knowledge transfer process without necessarily being rewarded with any benefits for the audience themselves (Peers and Brown, 2003, p 2). In the context of museum exhibitions, ‘co-production’ has been broadly defined by Davies as ‘a spectrum of activity across the production process, performed by a range of individuals and groups with a varying impact on the final exhibition’ (Davies, 2010, p 307). In 2008, Heywood loosely defined co-production as ‘a museum inviting in community members to help produce exhibitions’ but argued that the practice goes beyond ‘community consultation’ and requires ‘the museum relinquishing some of its power and being brave enough to allow input into curating the exhibition’ (Heywood, 2008, p 19).

The preference for reciprocal benefits for both museum and community members has been highlighted, pointing to what Phillips describes as ‘the collaborative paradigm of exhibition production’ where museum and community partners ‘co-manage a broad range of the activities that lead to the final product’ (Phillips, 2003, p 159). ‘Co-creative’ projects for Simon go a step further by often requiring ‘institutional goals to take a backseat to community goals’ (Simon, 2010, p 264). Yet Govier has put forward a broader definition of ‘co-creation’, that ‘is not always anchored to the representation of community interests, or predicated upon the hand-over of power’. Instead, she envisages the term straddling ‘Simon’s notions of “contribution”, “collaboration” and co-creation’: all of which involve working together with our publics to make something new. Govier notes her preference for ‘co-creation’ rather than the related term ‘co-production’ as ‘the former implies slightly more openness about where the collaborative journey might take all of the participants’ (Govier, 2010, p 3-4). Moving towards a fuller hand-over of control from museums to audiences, ‘genuine co-creation’ has been described by Sally Macdonald as the situation where museums act as facilitators, rather than as creators themselves (Macdonald, in Atkinson, 2010). This facilitation model is what Simon has termed ‘hosted’ projects, and has also been termed ‘radical trust’ by Lynch and Alberti (2010). Expanding on this term, Lynch and Alberti explain:

In practising radical trust, the museum may control neither the product nor the process. The former – if there is one – will be genuinely co-produced, representing the shared authority of a new story that may then have a knock-on effect in the rest of the museum. But the process itself is the key issue, and it may not be outcome oriented at all. Consensus is not the aim; rather, projects may generate ‘discensus’ […]. [Participants], including museum staff, may develop new and radicalising skills as ‘citizens’ during this process.

p 16

For the Information Age team, the multitude of terms used in the wider field was confusing and open to misinterpretation. Moreover, a lack of a shared understanding of the practice and the implied assumption that meaningful participation must be predicated upon the relinquishing of authority by the museum to its community participants (and the associated critique of participatory practice that fails to embrace this ambition) also posed new challenges for the team in understanding and reflecting on their work.

The gallery team eventually settled on the umbrella term ‘participation’ (over ‘co-curation’), which could encompass the Museum’s existing understanding of processes of ‘consultation’, ‘contribution’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘co-creation’; terms which were largely influenced by Simon’s framework for understanding participation in museums (Simon, 2010). From the outset, care was taken to define, as clearly as possible, the different forms of participation that would be utilised by the Museum in working with groups to develop the gallery.

For the Museum:

- ‘consultation’ involved inviting specialists (for example teachers or subject experts) as well as non-specialists (such as local or new audiences) to help identify particular audience’s expectations, needs and wants, thus informing the Museum’s practice. Consultation was felt to be ‘participation’ when it resulted in a sense of shared ownership of ideas, and where the conversation was two-way between the Museum and participants. An example is consultation with the British Vintage Wireless Society who contributed collections knowledge and expertise to the Broadcast Network;

- ‘contribution’ involved asking for and receiving content from audiences. This could be in the form of assistance in the collecting of contemporary objects, the contribution of stories and experiences to shape interpretation, and user-generated content for display, both online and on-site. This process was understood as a long-term commitment from the Museum, which necessitated contributions being treated respectfully and preserved in the same way as other museum artefacts and knowledge. For example, the oral histories of women who worked on the Enfield Telephone Exchange were recorded and are now preserved as part of the Museum’s collection;

- ‘collaboration’ described open-ended collaborative activity with participants where the Museum set the concept and outline plan (for example, the area of the gallery and the possible final form of the output). Staff then worked with audience groups to develop the detail and make it happen. This would often involve the audience defining and deciding on what content was relevant, as was done by the volunteers and museum partners who categorised and sorted the telegrams during the community collectors project showcased in the Cable Network;

- ‘co-creation’ was defined as ‘creating an output together’, with shared ownership of the concept between participants and the Museum. In this participation scenario, the Museum gave audience groups the skills and tools to deliver an outcome, and staff worked closely alongside them to support their activities. The goal was shared between Museum and participants. Co-creation as it was undertaken at the Science Museum required the Museum to involve audiences from the start, a good example being the work with the London Cameroonian community to produce an exhibit on mobile phones.

Following Simon (2010), the Science Museum worked to achieve a spectrum of participation, resisting a notional hierarchy which pitched some approaches as naturally better than others. Across this spectrum, different activities involved different levels of involvement by participants and resulted in different outcomes. This approach drew inspiration from Simon, who has argued that one form of participation is not necessarily better than another,[4] and from Govier who has questioned the explicit and implied assumption in debates surrounding participatory practice that equate ‘the greatest yielding of institutional power with the most valuable kind of participatory work’ (2010, p 4).[5]

Embedding participation in gallery development

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/006Using the above definitions rather than an ambition to transfer authority to participatory groups, staff within the team worked together with diverse groups, through several distinct activities, to explore themes, create content and influence the interpretation of the Information Age gallery. All forms of collaboration – short and longer term, where the outcomes were pre-defined or more open-ended in nature – were all deemed legitimate and worthwhile where mutual benefits could be identified.

From the outset the notion of participation was deeply rooted in the core ambitions of the Information Age gallery. The subject matter of the gallery was identified as especially appropriate, both because of its universal relevance, and because of the determination to focus on the stories of ordinary users as much as the inventors and innovators of technologies – and the timing within the museum was right for an ambitious plan to develop a permanent gallery in this way. With this in mind a broad range of participation and co-creation activities were proposed as part of the Heritage Lottery Fund Activity Plan for the gallery, ranging from consultation with experts through to in-depth programmes to collect objects and stories for inclusion within displays. Whilst some activities were viewed by team members as an extension of consultation and other community-based activities, which had already been trialled and successfully delivered by the Museum, it was clear that some activities required staff to develop new skill sets or take greater risks in connecting with audiences that had not previously engaged with the Museum (see Appendix for a list of participation activities).

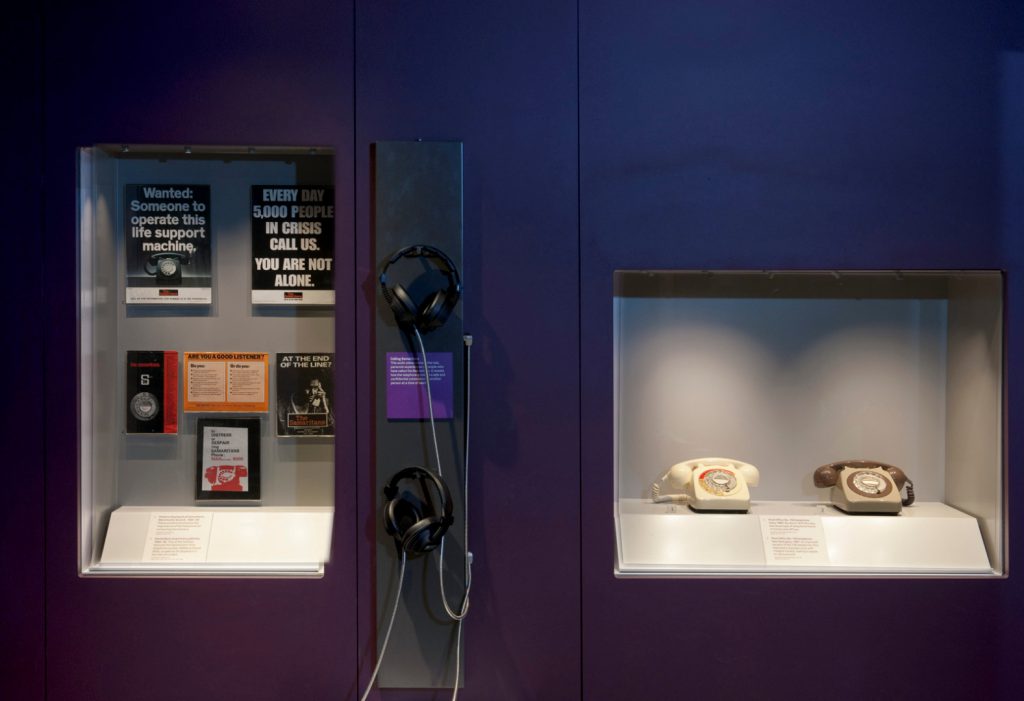

Groups and individuals were invited to participate because of the relevant experiences, expertise and insight they could share with the Museum. For example, Samaritans volunteers were the most relevant and appropriate group to work with when telling the story of the Samaritans as an organisation. Their first-hand experiences of being the listener at the end of the phone line brought a powerful and personal perspective to the narrative which curator-led research could not provide. Similarly, members of the London-based Cameroonian community were ideal spokespeople for exploring the impact that mobile phones have had on Cameroon as they have witnessed the dramatic change which the technology has brought to their homeland.

For the Information Age team, participation was integral to the development of a gallery that could engage the broadest possible audiences. It was important, however, for the Museum to be explicit about what the participation projects were not seeking to accomplish. For example, whilst the process of relationship building with the participants and community groups involved was important to the success of each project there were no long term engagement plans beyond the life of the gallery development. Rather, the goal of working with a range of groups was to influence the Museum’s thinking, to add expertise and experience not present within the gallery team, and to produce outputs that would be more accessible and would have wider resonance and appeal than could be produced without the input of additional participants. The processes of involvement, it was hoped, would generate value and benefits for participants, and indeed early analysis of evaluation suggests that this was the case (see below). But the primary motivation for collaborating with diverse groups was the development of a more engaging and accessible gallery for all visitors.

Towards a research-based practice

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/007In 2014, Lord and Piacente wrote, ‘We are moving past the initial excitement of participation “because we can” into participation where quality is sought and valued’ (2014 p 168). Indeed, there is growing recognition that participatory practices, shaped by a commitment to creativity, diversity and inclusion, can bring a more bespoke or responsive voice to museum work that facilitates the creation of new meanings (Flinn and Sexton, 2013) and, in doing so, results in richer, higher-quality outputs. Yet, despite a widespread belief that participation in museum work is good for everyone, there is little consensus on how the value of participatory work can be understood and captured, described and measured.

The scale of the Information Age gallery meant that the Museum invested significant resources in evaluation and research. An ongoing process of evaluation produced findings that could support the team to refine their approach to participatory practice as the project developed. Research activities were directed towards addressing not only internal, institutional gaps in knowledge (for example, around the implications of scaling-up participation beyond small-scale projects) but also to exploring gaps within the broader literature on participation, as well as exploring the staff and participants’ experiences of working in this way.

In attempting to build a culture of reflection among the project team, individual staff members were encouraged to be actively involved in a process of internal evaluation. This was designed in collaboration with researchers from King’s College London and was administered by them at the start, during, and at the end of the project. The aim was to capture staff and stakeholders’ attitudes towards, and experiences of, participatory approaches from the very beginning of the project through to the gallery’s final delivery. The Museum aimed to map this attempt to embed participation within all aspects of a major gallery development to see how a large project that touched upon and impacted so many different teams within the Museum could start to change not only attitudes towards (and acceptance of) collaborative ways of working, but also to stimulate changes in working practices and policies.[6]

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the decision to place participatory practice at the heart of the development of the Information Age gallery from its inception was regarded by team members with a mixture of scepticism and apprehension as well as excitement and enthusiasm. Some expressed anxiety about embarking on collaborative methods of working with which they were unfamiliar; others had concerns about impact of participation on the quality of the gallery interpretation or the potential loss of institutional authority.

There was also a very real concern that the added time and efforts needed to work in this way may not produce a valuable output and one deemed to be sufficiently different from previous galleries to warrant the extra resources given to participation activities. In order to address anxieties and build confidence, training, skills workshops and awareness-building sessions were delivered to all staff members, and extra advocacy support (by specialist participation and audience-focused staff) was provided for the teams to ensure that their concerns were listened to and addressed during the gallery development process.

During the participation projects gallery staff became fully embedded in the participatory activities as equal partners along with the public participants and engagement staff. Early analysis of the internal evaluation suggests that this exposure to the processes of participation and contact time with the participants led to a more enhanced appreciation of the value of this approach among Museum staff than had been experienced on previous projects.

Museum evaluation was also concerned to gauge the impact of the projects from the perspective of the participants.[7] Throughout the evaluation participants reported a sense of enjoyment and pride from being involved with the projects (‘…this was a real opportunity for our voices to be heard…’, Cameroon project participant, 2014), emphasising a sense of ownership and responsibility for the finished products. Many of the participants also claimed that the projects had exceeded their expectations and that, along with the chance to get involved and see the workings of exhibition developments, they had also learned new skills they might not otherwise have had an opportunity to develop, and were given an opportunity to make their own contribution to a permanent public space (‘…we are part of the artwork, it’s part of us…our names are in that gallery…’, Art Project participant, 2015).

As with many participation projects, not all of the team’s plans to involve groups were realised due to shifts in content direction, a failure sometimes to find meaningful modes of participation, and limitations on time and resource. There was also a marked gap between the ambition of staff and the reality of what was possible during content and interpretation development. Not all participants derived the benefits that the Museum had hoped they would, for example when their interests and experiences did not naturally fit with the aims and ambitions of the project. This was the case for one particular project with young people from Bede House, a community support organisation with a base in Bermondsey. The project was based around technology (early telegraphy) prevalent at a particular point in history (the 1920s) which was unfamiliar to the young people. Although the Information Age team had hoped to find a modern relevance for this among a teen audience, the group could find few tangible connections with this topic. It was quickly decided that instead of forcing a link that would look and feel artificial and tokenistic, to both the participants and the Museum, the team would limit the project to just this initial exploration rather than a longer term relationship (McSweeney, 2011).

Six months after opening Information Age has been visited by over 400,000 visitors.[8] A major evaluation investigating visitors’ responses to the gallery is currently being undertaken, including questions about the effectiveness of the participatory elements. The Science Museum is committed to understanding how far the ambition to enrich the gallery experience for all visitors through a participatory approach has been realised and to exploring what a ‘valuable’ encounter with participation outputs might be for audiences.

Conclusions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/150305/008Given the relative infrequency of large-scale permanent exhibition developments across the sector and the considerable complexity bound up in their making, it is unsurprising that existing models of participation largely reflect practice within smaller scale projects and attempts to build relationships with local, geographically defined communities. At the same time, there is a need for more research and debate around how museums that are primarily national and international in scope and reach can meaningfully involve audiences in their work. There is also a need for an enhanced understanding of the benefits that are generated by such participatory activities for museums, participants and visitors alike.

The approach to participation taken with the Information Age emphasised the need for mutual benefits for both the Museum and participants from engagement and involvement with a large scale, high profile and permanent output. Various activities and techniques across different fields were drawn in under the banner of ‘participation’, and all forms of involvement, with different levels of authority-sharing, were valued by the institution. Large-scale exhibitions require the involvement of multiple teams and various skills. That these teams on the Information Age gallery included individuals and groups drawn from outside of the museum, with diverse forms of expertise and insight, was considered a strength. At the same time, whilst the making of the gallery involved new ways of working, of eliciting and valuing contributions from communities outside of the Museum, the drive for participation was not based on an attempt to hand over power to these groups.

Current professional and academic debate questions the implications for expertise, and for quality, of increasing experimentation with participatory practices in museums, often highlighting the risks as well as the advantages potentially created by the sharing of power or authority with constituencies outside of the institution. For the Science Museum, although this was the first time that participatory work had been embedded within the process of developing a large scale permanent display, the approach was conceived not as risky or radical but rather as building on and extending existing exhibition development practices that could draw in a range of perspectives towards a more inclusive shared output.

There were, of course, limitations in what could be achieved; forming new partnerships was rewarding but meant entering unknown territory, so planned outcomes were not always possible. However, ongoing evaluation and opportunities to reflect on what was working and how emerging problems might be addressed helped to move the Museum forward. The methods and approaches utilised – and the lessons learned – in the creation of Information Age are by no means fully resolved. Rather, they constitute an experimental work in progress, a possible way forward for the Museum to explore the embedding of participation in the core of its work.

Further research is needed to address the many questions posed by this attempt to embed participatory practice at the heart of the Museum’s work. Would more flexibility in outputs have been feasible with a development of this kind, and would it have resulted in higher quality outputs? What are the challenges for museums in further developing and embedding participation in times when, in some organisations, staff with specific experience of community engagement are being let go (Nightingale and Mahal, 2012)? How are visitors’ experiences of galleries changed by the adoption of participatory practices in creating museum narratives? Fundamentally, to what extent does the kind of participation facilitated in the development of Information Age foster greater inclusion and access for all?

Large organisations can and should play a key role in helping to explore these questions, and must find ways of working that engage the public more fully in the sector. What remains clear is that this requires continual questioning around the assumptions and ideas that shape the formation of participation and its discourses, and how these might support or hinder work across very different museum and project contexts. Moreover, in order to develop a more critical body of knowledge on participation in large museum contexts, the sector must expand upon ways of sharing existing practice and experiences across institutions of all kinds.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text