Obituary: Brian Bracegirdle (1933-2015) at the Science Museum

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160610

Keywords

Brian Bracegirdle, obituary

Obituary: Brian Bracegirdle

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160610/001The South Kensington Museum and its offspring, the Science Museum, had little to do with medical history until the 1970s. Indeed, the official title of the latter, the National Museum of Science & Industry, seemed to make that point clear. An indication that change was in the air was an announcement early in 1973 by the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine that negotiations had begun with the Science Museum for the transfer of its very extensive collections to South Kensington. These had originally been garnered under the guidance of Sir Henry Wellcome up to the time of his death, in 1936. The institute’s rationale for this change was that it wished to concentrate on becoming a centre for research at postgraduate level, based on its library, and that it was intending to form an association with the University of London. The change was being strongly promoted by the Keeper of Chemistry at the Science Museum, Frank Greenaway, who was advising his Director, Margaret Weston. A transfer agreement was formalised in June 1976. The collection was to be transferred on indefinite loan and a new department would be established, the Wellcome Museum of the History of Medicine. Funding was to be made available for five years, after which the Science Museum would assume financial responsibility.

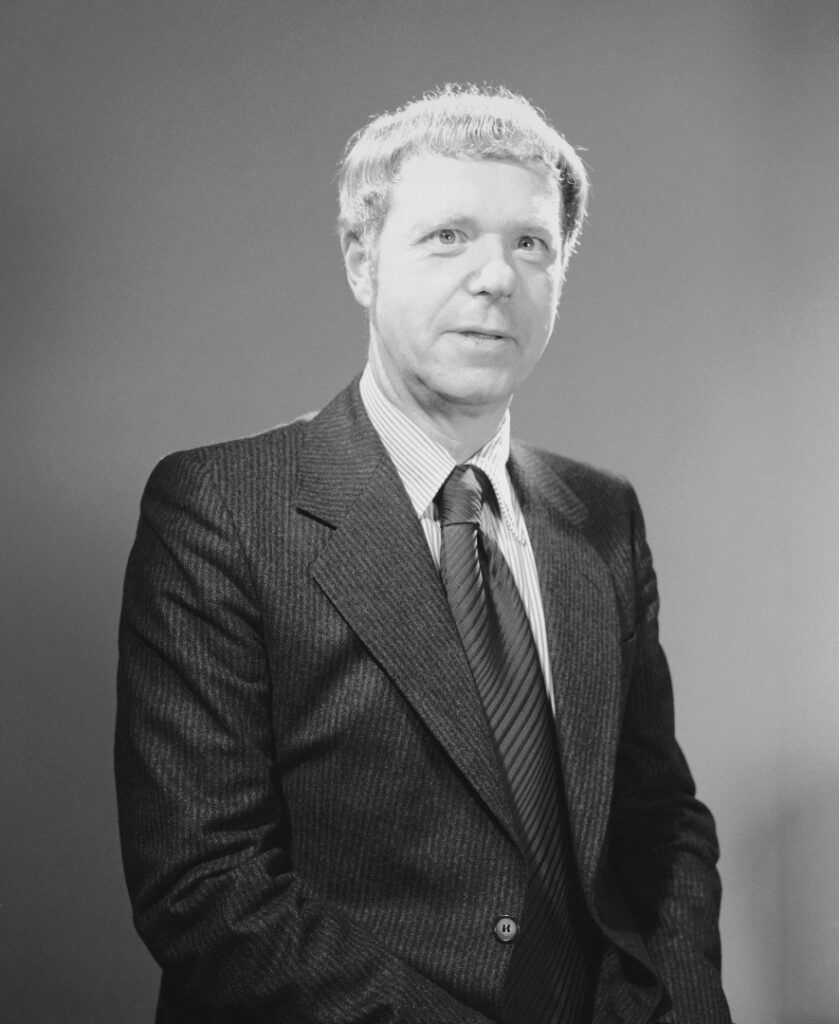

The next thing to do was to set up the new department and the post of Keeper of the Wellcome Museum was advertised. The successful candidate was Brian Bracegirdle, who joined the Science Museum in 1977. On leaving school Brian, who came from Macclesfield in Cheshire, had first worked for ICI’s dyestuffs division. His degrees were taken extramurally and he developed a passion for microscopy. From 1964 until 1976 he taught biology at a London college of education. He also developed a deep interest in industrial archaeology, a discipline then in its infancy, which he centred on Ironbridge in Coalbrookdale, Shropshire, described as being the home of the Industrial Revolution in England. Before he had arrived at the Science Museum he had published The Archaeology of the Industrial Revolution (1973), Thomas Telford (1973) and The Darbys and Ironbridge Gorge (1974). Perhaps more importantly to him, he had authored many books on medical, zoological and botanical topics, illustrated by high-quality photographs he had taken himself (he was an expert photographer). About ten of these atlases came out between 1966 and 1978 (some co-authored with his wife, Patricia Miles, and others), and there was the same number of books about current microscope technique and its history, up to 1995. Brian was an astonishingly prolific writer.

As Keeper, Brian set about his task of establishing a new department, hiring staff and having them register, using newly developed computer techniques, between 100,000 and 165,000 objects (depending on how they were categorised; some were transferred to other, more appropriate museums). He also created a library of medical works, set up an acquisition policy (memorably, he had said to a journalist, ‘Mind you, I don’t want to be sent everyone’s old trusses’) and established two large galleries illustrating the history of medicine. All this was achieved in five years. To stick to this timetable he had to be brisk and impose his briskness on his staff, of whom there were about 30 at the peak. Most of these were cataloguers, working in a somewhat basic warehouse in Enfield, in the basement storage area of the Euston Road building, and in the Science Museum itself. He was a strict manager, which suited some and not others, but he was an effective choreographer. The department certainly felt a sense of driven mission.

Brian took a particular interest in one of the galleries, which he curated himself. This was Glimpses of Medical History, a series of large-scale reconstructions including, for example, Thomas Beddoes’ Pneumatic Institution at Bristol in the 1790s and a contemporary operating theatre for open-heart surgery. These were interspersed with small-scale dioramas previously displayed in Euston Road. This, the first permanent medical display ever seen in the Science Museum, was opened by Princess Alexandra in December 1980. The upper Wellcome gallery was larger and more complex in its organisation. It was curated by Christopher Lawrence (who had earlier worked as a general practitioner), seconded from the Wellcome Institute as its Senior Medical Historian, and Robert Anderson, seconded internally from the Chemistry Department, of which he was Keeper. Also key to the curation of the new gallery was Ghislaine Skinner, appointed Assistant Keeper in 1979. Installation of the gallery was under the control of Derek Robinson, a chemist who became Keeper of Museum Services. The basic premise of the gallery was to display Sir Henry Wellcome’s collection in all its chronological and cultural breadth, while making sense of topics in medical history that could be illustrated by material objects. Opened in 1982, the result was, unsurprisingly, large and complex. The two galleries had a long lifetime, only being dismantled in 2016.

These massive tasks having been achieved, the department settled down to a more normal existence. The library continued to grow with Wellcome support and acquisitions were sought to represent more recent medical practices. Registration of the collection continued. The Second Conference of the European Society of Medical Museums held some of its sessions at the Science Museum in 1984. Margaret Weston retired in 1986 and Neil Cossons was appointed Director. Brian assumed the newly created post of Head of Collections (though only in an ‘acting’ capacity) in the following year. It is no secret that frequently he did not see eye to eye with the new Director, and Brian was ousted in 1987 under an early retirement scheme. He became a Museum Fellow and worked at Blythe House on microscopes. Here he was able to concentrate on doing what he had long sought, to create the definitive catalogue of the huge and comprehensive microscopy collection. Many of these objects had entered the Science Museum much earlier as the Clay and Court Collection. After many years’ work, this mammoth task resulted in A Catalogue of the Microscopy Collections at the Science Museum, London, which as issued as a CD. He took early retirement in 1989.

Brian did not have a subtle personality, though his toughness suited the task at hand. He was a determined fighter, which was made clear when he had a severe heart attack in the Alps and required a triple bypass operation. He recovered fully and even this did not keep him away from the Museum for long. He enjoyed being sociable with particular friends and he could be a warm host. He started organising annual port parties at his home in Limerston Street, Chelsea, for his male friends; they were most definitely for those who possessed trencherman’s appetites. These continued when he moved out of London, to Cold Aston in the Cotswolds. Here it was that he indulged in another of his obsessions, large-scale model railways, with trains running round his garden. Eventually he moved to Cheltenham, and it was there that he died. He specified that there was to be no funeral or memorial, and that his body was to be bequeathed for the purpose of medical education.

It seemed particularly apt, a few months after Brian Bracegirdle’s death, for the annual reunion of Science Museum staff to take place for the very last time in the Fellows’ Room*, surrounded by the thousands of books that had been acquired by Brian to create a working library for his newly established department.

* This part of the building had recently been sold to Imperial College.

Further reading

- Boon, T, 2010, ‘Parallax error? A participant’s account of the Science Museum, c. 1980 – c. 2000’, in P J T Morris (ed.), Science for the Nation: Perspectives on the History of the Science Museum (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), pp111–35

- Bracegirdle, B, 1982, ‘Displaying the history of medicine: the Wellcome Museum in the Science Museum’, Journal of Audio-Visual Media in Medicine, 5, pp124–9

- Croome, A, 1976, ‘Wellcome to the Science Museum’, New Scientist (16 December), p639

- Symons, J, 1996, Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine: A Short History, see https://archive.org/stream/Symons1993/Symons_djvu.txt

Personal reflection

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160610/004To a young museum assistant Dr B was a formidable persona even before I met him. This was partly due to me having a copy of his Atlas of Plant Structure at home (the then standard text for all A-level biology and undergraduate botany students) and partly departmental mythology. I was warned that he was a ‘stickler’. I finally met him some three months after my appointment in January 1983 – he had been off work recuperating from his heart surgery. At that meeting he warned me that the Museum was a bit of a swamp and that there were a lot of crocodiles out there. Over time I came to understand something of the ‘stickler’ descriptor: he was a stickler for the use of academic titles; he was a stickler for punctuality; and he was a stickler for doing things properly. It was not so much that he did not suffer fools gladly, it was more that he did not suffer fools at all and he would be forthright in telling you so. But, if you met his exacting standards, responded intelligently and with respectful confidence, then occasionally you would catch a twinkle in his blue eyes and the hint of a smile.

I was allocated day-to-day care for a number of collections for which he had a specific responsibility and, more importantly, collections that held strong personal interests for him. His interest was frequently hands-on, which meant not just a prompt retrieval of items from store but there were times when I had to remember how to use a microtome and even how to mix formalin.

There were certain things, as Dr B’s museum assistant, you learnt very quickly not to mention. One was that if you could not find a microscope he had asked for then check ‘his’ cupboard in the Lower Wellcome Gallery but never mention that’s where you’d found it. Another unmentionable was the ‘other’ cupboard, the one that contained a remarkable number of bottles of port.

His interest in ‘his’ collections was in the spirit of the Museum at that time in that the objects would be used for purposes of demonstration and research. Dr B’s entry in his Brighton run was not an early Benz but photomicrographs of images gleaned from specimens in the histology collection, or from original microscopes. He never said much about this work but I knew he was utterly meticulous. The challenges of taking photographs of images produced by historic microscopes are considerable. I remember being staggered when I was helping him with the Leeuwenhoek exhibition that he had managed to get photographic images from Leeuwenhoek’s original microscopes. He was a teacher and the point of these images was not just the personal satisfaction of getting the shots but that they could then show everyone exactly what it was that Leeuwenhoek saw some 300 years earlier through his little beads of glass. I think he took a quiet pleasure and pride in presenting these images for the Museum’s visitors.

One of my other strong memories of that time came from my cataloging duties in the Fellow’s Room. Dr B would acquire books by the box load but cataloging the Wellcome objects had taken precedence over the books, several thousands of them. My job was to sort and catalogue them. In the process of doing this I came across a beautiful tome bound in white vellum, with text in Latin and glorious woodblock images. At first I thought it was a facsimile as it was in such pristine condition. Further exploration revealed a title page and a date: 1543, De humani corporis fabrica, Andreas Vesalius. My jaw dropped. I took the book over to Dr Bracegirdle’s office, with a pair of clean white cotton gloves. Sometime later he chuckled at my suggestion I take the book over to the Library for safe storage with the other rare books. And, as I went out of the door, he told me I’d better go and check all the other shelves in the Fellow’s Room. In all, about a week later, I took about a dozen pre-1800 books over to the Library for safe keeping.