Why the anonymous and everyday objects are important: using the Science Museum’s collections to re-write the history of vision aids

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201306

Abstract

The history of nineteenth-century spectacles and eyeglasses is unusual in the extent to which it has incorporated objects and material evidence. However, both collectors and historians have favoured the pristine object or the object with noteworthy providence at the expense of more utilitarian frames. By drawing upon my experience as a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership (CDP) student at the Science Museum, this article reflects on how large anonymous and primarily uncatalogued collections can be fruitfully used in historical research. By case-studying the retail and design of vision aids, it argues that everyday or anonymous objects – the broken, scratched, un-named – are a valuable historical source. It highlights the usefulness of material culture for exploring the experiences of use or of users that otherwise leave little trace and proposes how problems of interpretation can be overcome through the study of a range of additional sources: business records, trade catalogues, advertising material, imagery, popular literature and medical literature. Whilst researching an anonymous collection is labour-intensive, the material evidence of utilitarian and noteworthy spectacles and eyeglasses allowed the experience of nineteenth-century vision aid wear and vision testing to be fully explored and communicated to both an academic and non-academic audience.

Keywords

anonymous collections, historical methods, material culture, Vision aids

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/In May 1871 a column called ‘Table Talk’ in a weekly periodical postulated that ‘spectacles are worn by so many people nowadays that we are inclined to wonder how former generations managed to get on without them’.[1] Then, as today, spectacles and eyeglasses were ubiquitous and their benefits were acknowledged. It is therefore perhaps surprising that spectacles and vision testing have received little historical attention. Their histories have been predominately written by collectors of vision aids and ophthalmic antiques and, within these, the nineteenth century is particularly under-studied. The nineteenth century was a key period in the development of British vision aids; it saw the foundation of vision testing based on observable scientific principles and a subsequent acknowledgement of the utility of lenses to enhance people’s vision. Vision aids had long been produced in a variety of artisanal contexts and were neither scarce nor expensive in Europe from as early as the fourteenth century. Indeed, England was purported to have imported thousands by the century’s close (Illardi, 2007). In addition, by the seventeenth century, they were readily available across classes in Britain (Withey, 2016). However, developments in knowledge of the eye and processes of manufacture marked a fundamental shift in the use and understanding of vision aids as a functional, enhancing device in nineteenth-century Britain. Distinctive change is best illustrated by comparing this period to the preceding century. Steel and other metals were introduced into the manufacture of spectacles and, from the mid-eighteenth century, a range of decorative polished metal frames began to emerge, altering both the sites of production and meaning of spectacles (Withey, 2016). Spectacles, as a result, were sold by a variety of instrument and ‘toy’ makers as well as becoming increasingly more public when worn. Yet, while a potentially quotidian item in a retailer’s diverse range of more expensive stock, they were not mass-produced; a pair of spectacles remained above the price of a shilling and they were a specialised, even bespoke, item. The eighteenth century therefore was important in broadening materials for spectacle usage, helping to remove some of the prejudices associated with spectacle usage, establishing spectacle side-arms and foregrounding the fashionability of certain frames in Britain. However, it was in the nineteenth century that frames could be secured to the face unaided for the first time and were mass-produced in uniform styles, meaning that spectacles could be obtained for pennies, and their retail, use and marketing potential expanded exponentially.

In addition, with the exception of Alun Withey, spectacles have predominantly been explored from a scientific perspective by historians. These studies have focused on optics and spectacles as instruments of vision, with a particular concentration on the role of the optician and the broader scientific instrument maker.[2] While important, historians have not explored the vision enhancing properties of spectacles from a medical perspective. The role of ophthalmologists more broadly has often been dismissed and studies have generalised their opinion and views towards spectacle use, arguing that medical practitioners failed to appreciate their value for most of the nineteenth century. This has marred our historical understanding of vision aid use and the distinctiveness of the nineteenth century as a key period of change. The use of spectacles shifted in the 1850s and 1860s from an abstract understanding of the principles of optics to one that was based on the observable refractive condition of a person’s eye through the use of the ophthalmoscope. While not the focus of this article, changing understandings of visual capacity and the functionality of spectacles altered how they were marketed, retailed and consumed. The range of conditions that spectacles were able to treat expanded and therefore the number of prospective users multiplied. Rather than a tool to aid reading – or to remedy severe short sight – spectacles were expected to accommodate conditions that demanded 24/7 or long-term wear. A range of suppliers therefore had new theories to draw upon in order to ‘sell’ their products, and expanding sites of vision testing and spectacle use gave mass production of a variety of new frames economic viability. Spectacle usage was truly ubiquitous and alarming to contemporaries by the end of the nineteenth century and, while it had been within reach of all classes for two centuries, there was a consensus that they were now considered an indispensable, and necessary, device for a broader range of people in all echelons of society.

The prioritisation of the object by collectors, and the lack of acknowledgement by historians of the benefits of collectors’ works and approach, has limited previous historical interest in the topic. Collectors have researched important information on the manufacture, design and use of vision aids in nineteenth-century Britain, including the popularity of certain designs and materials.[3] These findings are informed by a particular approach that often focuses on key designs and collectors’ interest in overall value and rarity, as well as the object’s association with significant manufacturers, owners, events and provenances. Twentieth-century collecting practices are reflective of a wider twentieth-century academic tradition, which focused on luxury products or ‘high’ culture (Hamling and Richardson, 2010, p 13). Both collectors and historians paid attention to a certain cross-section of objects and prioritised these objects over other forms of evidence. The objects that bear evidence of wear or the trade literature associated with an object made by a lesser known individual, for example, were often avoided in favour of a pristine example with a more notable provenance. Such a focus, while essential and beneficial for exploring key and influential changes in design, fails to explore the everyday and is unable to tell us much about the experiences of a broadening number of users.

Research by collectors that have made more effort to consult additional forms of evidence, or have considered the types of users and functions of the frame, have shown the potential of objects – when used alongside other forms of evidence – to reveal the everyday experience of spectacle wear.[4] Similarly, the cultural turn in the second half of the twentieth century shifted focus to the ‘everyday’ and history from below, as well as the mundane or small object (Hamling and Richardson, 2010, p 13; Pennell, 2009). Within this, historians, like collectors, have highlighted the value of material evidence for illuminating the daily practices of ordinary individuals and groups of people. The primary challenge of my doctoral research was to expand collectors’ and historians’ earlier approaches further in terms of the number of objects consulted and the types of additional evidence used. As a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership (hereafter, CDP) between the Science Museum and Swansea University, my research drew upon two of the Science Museum’s collections: Matthew William Dunscombe’s collection of 289 spectacles and eyeglasses and over 1,000 spectacles and eyeglasses from Henry Wellcome’s medical collections. I had one primary research question: what do the Science Museum’s collections reveal about the everyday experience of vision aid use in the nineteenth century? As Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson have shown, the use of the term ‘everyday’ does not necessarily mean ‘low’ or common culture (Hamling and Richardson, 2010, pp 13–4). Rather, it is a focus on objects or practices that form part of daily life, which encompasses both the luxurious and the cheaper object. However, while I had a large source base of both types of object to draw evidence from, the utilitarian nature of spectacles meant that the collection was predominantly anonymous. The cataloguing was incomplete and nothing – or very little – was known about the provenance, acquisition and use of many of the objects. Approaching ‘anonymous’ everyday objects presents its own specific challenges. More conventional challenges associated with ‘named’ objects – a term I have chosen to denote objects that have detailed information surviving about their provenance, acquisition and/or use – include using material evidence to simply illustrate historians’ wider arguments gleaned from other, primarily textual, sources. In contrast, anonymous objects challenge how we interpret objects in the absence of any obviously relevant textual evidence (Hamling and Richardson, 2010, p 10). To mitigate the problems of interpreting a number of objects with little surviving information, I needed to develop a methodology that would incorporate a greater number of objects and a greater number and range of additional sources. My research findings showed that largely anonymous collections should not be viewed with suspicion. Anonymous collections can be fruitfully used to explore the design, use and function of an object and the richness of these findings inform more than a museum’s object catalogue. Indeed, in this example, the objects revealed new perspectives on a range of nineteenth-century historical themes, including industrialisation, education, transport methods, scrutinization of the workplace, and the growth of print.

Objects are a new and increasingly used source in a range of histories that intersect with the history of nineteenth-century spectacles and vision testing, including the histories of science, medicine and disability. The rising profile of material culture in the history of science, for example, has been attributed to the emergence of the history of museums, the historical work done by curators and a greater interpretation of museum exhibitions and catalogues (Mosley, 2007, p 291). While more work could be done to incorporate the use of objects as a source in the history of science, the value of objects for interpreting the past has been acknowledged. Additionally, in disability history the materiality of prostheses has received more focused study. Prosthetics and artificial limbs have long been collected, but museums are now more committed to documenting and displaying patient stories (Goggins, Phillipson and Alberti, 2017). The material form of assistive technologies has been simultaneously recognised by historians as a useful source for exploring users, consumption patterns and changes in design (Ott, 2002). In the case of users, material culture offers unique insights into agency and control by allowing the historian to explore how individuals adapted and customised their own devices (Oudshoorn and Pinch, 2005; Williamson, 2012). While not the focus of this article, it should be noted that vision aids contribute to these studies by highlighting how users both adapted their frames to increase comfort and wore them in a variety of different ways so as to repurpose the meanings of the device and enable its retail to exist as part of more mainstream culture.

Historical interest in the materiality of objects is reflective of broader changes in the utilisation of objects in historical research. Earlier approaches to material culture, for example, have been informed by anthropology and have tended towards object biography (Appadurai, 1995). As will be seen, and as has been shown in more recent studies, object biography and close study of a single-object still remains a valuable method for using objects to inform the past (Murnane et al, 2019). Moreover, object biography is a necessary research tool for understanding and contextualising the relationships between people and the meaning, purpose and use of an object.[5] However, an object’s biography does not need to be the sole focus or object of a study. Sara Pennell, for example, has pointed to the challenges of object biography, in terms of scale, for exploring historical issues of uniqueness and typicality (Pennell, 2009). Moreover, choosing to focus on object biography makes sense when the object has a range of surviving information about its provenance, manufacture and use, as well as additional textual evidence and trade literature. However, it is a less fruitful approach for objects with fragmentary surviving evidence. This does not mean that this type of object is not useful. As historians have acknowledged, objects are able to create new historical questions or angles of historical enquiry (Mosley, 2007, p 291; Bennett, 2005, p 6). By adopting this approach, more anonymous objects can be used to help explore broader historical themes. For example, what does studying a single component of an object – such as weight or a design feature – across a broad sample tell us as historians? What is possible with an object sample of roughly 1,500? The CDP scheme broadens the scope and possibilities of object work by allowing the researcher to overcome a key practical limiter that historians often face: access to collections. As argued by other former CDP researchers, long-term object work and time spent in an object store influences a person’s experience and feelings of attachment or responsibility to the objects being studied (Hess and Geoghegan, 2015).[6] Additionally, I will propose that the length of time spent in an object store also influences how one can use objects as evidence. Consistent and long-term access enabled detailed object-study and close comparison of objects – with sometimes no information on the object’s provenance, manufacture or use – across two collections. The physical handling of these two collections to inform my analysis further reinforces the value of touch in historical research (Robinson, 2010, p 503). My experience highlighted how jointly studying anonymous or utilitarian objects alongside textual sources and imagery can develop new perspectives on existing historical arguments and open up new lines of enquiry.

However, museum objects cannot be viewed as unmediated historical records (Bennett, 2005, p 608; Alberti, 2005, p 562). The anonymity of objects therefore can be particularly problematic when assessing the representativeness of a museum collection. Despite this, as shown in a recent project to exhibit anonymous objects from the University of Cambridge’s museum collections, anonymous objects raise a number of questions of intrigue. These questions include: why is there little known about an object’s acquisition?; and, why is the maker unknown?[7] To answer these questions it is necessary to be more mindful of how the collections were shaped by their original collectors and by the larger collections that they were placed in following museum acquisition. To ensure representativeness, I paid careful attention to the motivations of the collectors, how objects were collected, and whether the collections covered the range of materials and designs that existed in the nineteenth century. Both collections included the range you would expect to find in a collection of nineteenth-century vision aids and the collectors’ different collecting practices complemented each other. Wellcome was interested in the everyday. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that many of his objects contain little information surrounding their use, because, for the few spectacles acquisitions that were recorded, they were acquired as part of larger auction lots of various miscellaneous items.[8] Additionally, Wellcome was interested in an ‘evolutionary’ approach to history, which influenced his acquisition of multiple sequences of similar or identical objects at different times to trace trends (MacGregor, 2009). In contrast, Dunscombe’s collection was more calculative and, similar to other collectors, favoured examples of key vision aid design or material. Dunscombe himself was a nineteenth-century optician and his contrasting collecting practices, interest and expertise provided a useful supplement for exploring the trends that emerged from Wellcome’s broader collection.[9] However, despite Dunscombe’s collecting expertise and focus, some of his objects also have very little associated surviving information. The anonymity of certain objects across both collections can be explained by the growing utilitarian nature of vision aids by the nineteenth century, which has influenced the way that objects have been collected and the problems collectors have faced in cataloguing them.

My methodology was structured around three primary research phases: initial object scoping; researching relevant textual and visual sources associated with relevant historical themes or identified retailers, manufacturers and users; and then a re-investigation of the objects and textual sources to inform the themes, topics and arguments that were emerging. It was not a one-way process of identifying key objects and undertaking further research. Instead, I combined two popular approaches to material culture (Hamling and Richardson, 2010, pp 8–9). In the first instance, I did begin with the object and move outwards to questions of historical significance, including the object’s function and use. However, I also generated research questions away from the objects and drew upon a variety of types of evidence, including the material, to interrogate them. The research process involved an iterative interchange of the information derived from textual, visual and material sources in order to develop questions and conclusions based on all three forms of evidence. The textual and visual sources that were used included: newspapers, periodicals, trade literature, business archives, professional journals, patents, correspondence, satirical imagery and photographs. This article will case-study two different approaches to illustrate how my methodology worked in practice. Firstly, it will explore how both the existence and absence of evidence on named and anonymous objects informed existing historical debates on the retail of spectacles. Additionally, these objects, when used alongside textual sources, show how the fragmentary information on the retailing locations of objects reveal perceptions about the objects’ function and how they were used. Secondly, it will show how close study of anonymous objects – including their weight, design features, damage or wear – reveal the wearing experiences of an object and the motivations or reasons for changes in design. Exploring the design of objects in the Science Museum’s collections provided insight into the daily use of vision aids and the potentially emotive human experience of wearing, repairing or adapting a vision aid. I argue that the everyday or anonymous object – the broken, scratched, un-named, and those objects lacking provenance – are a valuable historical source and highlight the usefulness of material culture for exploring the experiences of use or of users that otherwise leave very little trace.

Using retail to explore the named and the anonymous object

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201306/002The initial stages of my object work were influenced by the extent to which I could use object biography to analyse a largely anonymous collection. There were objects with surviving information. Just under ten per cent of the collection had a name associated with either its manufacture, sale or use. The names that were inscribed into the spectacle and/or eyeglass frames and cases were one of the first things I recorded as I familiarised myself with the collections. The named groups of people within the collection can be divided into three primary groups: manufacturers’ initials on the silver frames; the name of the suppliers either on the arm of the frame or the front of the case; and a small proportion of users. Information on the frames, including manufacturers initials and supplier information, offered numerous ways for exploring the sites and processes of spectacle manufacture and production. The named information allowed me to explore business records of, for example, Curry and Paxton in London and G.W. Proctor in Sheffield. The materiality of the frame, coupled with textual sources that had been gleaned from named information, allowed questions of skill, division of labour, and historical variation in these areas to be explored. In the study of Curry and Paxton, for example, it became evident that spectacles were produced by piece work and that production continued by hand – and was highly specialised – alongside the expansion of factory production. Despite this, case-studying retail is more fruitful in this current study for outlining how material evidence can be used in novel ways because it necessitated drawing upon both the material evidence and a much greater variety of additional sources to obtain any clear trends or findings of significance. In addition, as part of this research, I focused on the names of the suppliers as opposed to the manufacturers’ initials in the first half of the century because of the availability of sources – the users, for example, had no other traceable information – and because of the lack of historical work on how and where vision aids were sold between 1800 and 1850.

Exploring the named information on an object is not a novel approach for using objects in history. However, as part of my thesis, I wanted to explore whether I could apply the methods used to study the 88 named objects to the remaining 1000+ objects. Moreover, I chose to research why a large proportion of spectacles and eyeglasses left no written record and what this could say about the nature of vision aid retail. Additionally, my approach was novel for the history of vision testing and vision aids because a broad study of lesser known or unknown individuals had not been previously undertaken. The findings from the material evidence, both named and unnamed, were crucial in revealing the nature and distribution of spectacle and eyeglass retail. By tracing the names of the individuals in a broad range of sources, including trade directories, trade cards and newspaper or periodical advertisements – and using these sources to explore the retail of vision aids more widely – I was able to find out two important bits of information: the trade of the seller, and the location where they were sold. Yet the absence of information on the objects also raised a number of questions about the anonymity of vision aid retail, which was confirmed through the study of textual sources. Uncovering the retail information of named and unnamed objects in the collection revealed that spectacles and eyeglasses existed in a number of different locations alongside a number of different objects. Analysing these locations highlighted how using the makers and suppliers – including those that were anonymous and lesser known – in a collection can be fruitful for exploring the meaning as well as the retail of an object.

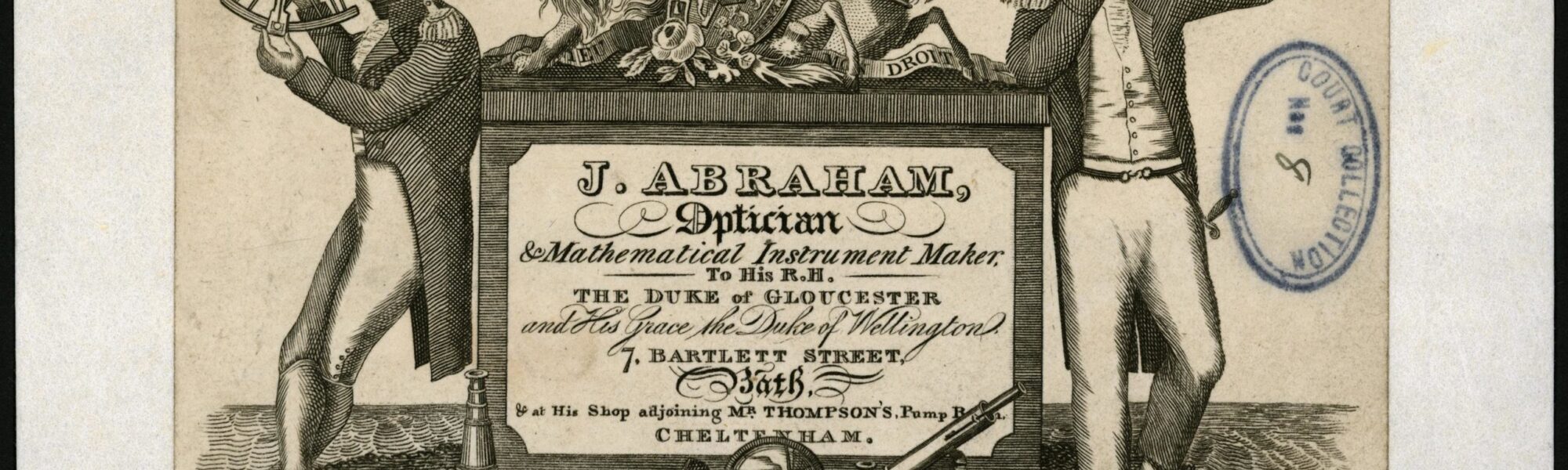

Eighty-eight suppliers were recorded following a search of trade directory records for names that were associated with a spectacle frame or spectacle case within the Science Museum’s two collections. Of these, standalone opticians were the largest number. Figure 1 shows that 33 individuals were described as opticians in their trade directory entries.[10]

However, Figure 1 also shows that there was a significant number of other traders associated with spectacles or spectacle cases and, collectively, these traders outnumbered the standalone opticians in the collection. While there were a few individuals that specialised as ‘spectacle makers’, the additional trades were predominantly associated with scientific instruments and include philosophical and mathematical instrument making. Additionally, there was also the ‘optician and goldsmith’ and an even greater proportion of frames and cases that were unmarked and left no trace of where they were sold. The information, or lack of information, on the objects in the Science Museum’s collections proposed that there were three primary locations for the sale of spectacles and eyeglasses: the broader scientific instrument trade, the jewellery trade, and the miscellaneous sundry or street trade that has often been referred to in previous histories.[11] Importantly, vision aids could be stocked alongside a range of other items. Eight suppliers in the Science Museum’s collections, for example, had a number of other instruments associated with their names and this range included: microscopes, hygrometers, kaleidoscopes, telescopes and saccharometers.[12]

The trade directory findings also document the location of sale and, specifically, that the spectacle and eyeglass trade existed in both London and the provinces. The location of the instrument trade outside of London has received focused study and a more significant body of instrument makers in the provinces has now been recognised (Morrison-Low, 2007, p 133; Clifton, 1995, pp xii–xiv). However, it has also been noted that objects often create misleading assumptions because a disproportionate number have survived with a London signature (Morrison-Low, 2007, p 285). Similarly, for spectacles and eyeglasses, while provincial examples existed in the collections, the trade directory findings suggest that the overwhelming majority of retailers were situated in London. Indeed, while the objects themselves are a rich source for instrument makers and suppliers, the material evidence suggests that the trade was predominantly London-based. Consequently, objects do allow you to conclude that suppliers existed in both London and the provinces, but reliance on these sources alone is not sufficient. By supporting the objects with a variety of documentary evidence, I was able to develop the suppliers’ names in the trade directory findings further and uncover methods of sale that were not documented in the named supplier information. Combining the study of trade cards, newspapers and periodicals allowed me to explore how retailers marketed spectacles and eyeglasses, what items they were sold alongside, and where they were sold.[13]

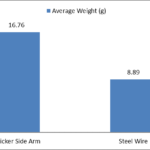

Figure 2[14], for example, illustrates how traders, such as J. Abraham, adopted royal crests, imagery and elaborate backgrounds as tools to bolster their reputation and help position themselves in the wider context of polite commerce (Berry, 2002; Stobart, 2008, p 314). Additionally, the advertisements that mentioned spectacles and eyeglasses between 1800 and 1900 in Gale Cengage’s 19th Century British Library Newspapers and ProQuest’s British Periodicals reveal the benefits and limitations of relying on objects with named information. At first glance, the newspaper advertisement findings reflected the findings from the material evidence: spectacles and eyeglasses were sold in the provinces and in London, as well as among a diverse range of traders. However, the object evidence was not able to fully reveal the diversity of vision aid sale. Spectacles and eyeglasses existed prominently in provincial city and rural locations. Additionally, studying the advertisements of opticians highlighted that opticians with a fixed address travelled outside of their localities to extend the sale of vision aids further. Typically, they arrived in a certain area for a fixed number of days and published in the local newspaper to bring public attention to their presence. Advertisements from Messrs Davis and Sons, based in St James Street in London and 3 Mulberry Street in Liverpool, illustrate the extent to which opticians could travel in this manner. Davis and Sons frequently advertised in a range of locations beyond their shop premises between 1837 and 1840, which included North Wales, the Midlands and the North of England.[15] Advertisements substantiate, and also greatly develop, the conclusions drawn from the objects that retail was both London and provincial.

Studying additional sources also helps in understanding and explaining the existence of a large number of surviving, utilitarian, spectacles. Trade cards and newspaper or periodical advertisements reveal that there was a great level of diversity of goods for both the standalone ‘optician’, the ‘optician and scientific instrument maker’, and the ‘optician and jeweller’. Within each advertisement, the position of spectacles and eyeglasses could vary from being a small, almost insignificant item, to the primary selling point. Indeed, in the absence of any significant business records, sources such as trade cards, catalogues and advertisements become invaluable for determining the position of an item in the wider trade of a scientific instrument maker (Whipple, 1951; Nall and Taub, 2016, pp 21–2). As shown in Figure 2, for example, spectacles were not the visual focus of the advertisement and appear the same size, or do not appear at all, amongst other scientific instruments. However, equally striking was the advertisement of spectacles and eyeglasses amongst sundry good trades for as little as a penny. Besides advertisements, the sale of cheap spectacles appears in fragmentary accounts of street sale in letters of correspondence, reforming publications such as Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor, and warnings against spectacle hawkers by ‘reputable’ retailers.[16] The marginal position of spectacles and eyeglasses amongst certain retailers’ stock, and their existence at an extremely low cost, raised a number of questions about how spectacles and eyeglasses were perceived. Indeed, studying the advertisements of spectacles and eyeglasses reveal that vision aids had a threefold function and position: a scientific item that could be sold alongside other instruments, a decorative fancy good that was equivalent to an item of jewellery, and a utilitarian, ubiquitous sundry. While it would be presumptuous to assume that all of the anonymised steel spectacles in the collections were sold as part of the sundry goods trades, the absence of any information surrounding an object is just as telling or interesting as the frames that contained a detailed level of information.

Studying the names associated with frames or cases in the collections has both its challenges and limitations. Remarkably, the 88 suppliers provide a fairly representative picture of vision aid retail that emerged from a broad comprehensive study of trade cards and advertisements. Collectively, the named suppliers revealed more than the location of sale, they highlighted the different places and contexts that vision aids fitted into in the first half of the nineteenth century. However, the anonymous items in the collection were equally important in this process; they promoted questioning about the place of vision aids amongst a retailer’s stock and the extent to which vision aids were utilitarian items in this period. Additional sources were required in order to answer these questions, but the objects nevertheless were a crucial starting point and are a piece of material evidence that is able to document the fragmentary textual accounts of street and sundry goods sales. There are also limitations when focusing solely on the named suppliers in the collection. One of the problems was the predominance of named information on spectacle cases. The lack of documentation surrounding these objects meant that it was not possible to trace or state with any certainty that it was the original case in which the vision aids were purchased. Consequently, it is only possible to state that the retailer sold vision aids, and it limits the ability of material evidence to be used as a source for exploring the relationship between a particular type of frame and the location of sale. Moreover, relying on the named information alone would have led to fragmentary conclusions about the location of the broader vision aid trade. The named and lack of named information informed and shaped my argument and promoted questioning about the sale and meaning of these objects. While the named information is useful, it does not necessarily bring out the full potential, or strength, of objects and collections as a historical source.

Studying design across the collections

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201306/003My study of vision aid design incorporated all of the frames – the anonymous and named – across both collections. Key objects have been used by collectors to illustrate the ways in which vision aid design changed. However, anonymous objects also lend themselves well to this usage and leave a clear visual record of how the design of spectacles and eyeglasses evolved. It is evident, by spending just a short amount of time in the Science Museum’s two collections, that vision aids changed fundamentally across the nineteenth century. Indeed, no textual source was able to document how design evolved as clearly as the objects. However, if I used the objects to simply document the ways in which vision aid design changed in the nineteenth century, the historian would likely answer, as one of my supervisors did in the early stages of my project, “So what?”. Faced with this challenge, I realised that the objects were able to do more than visually document design change; material evidence can also be used to explore why these changes occurred. Certain design features can be used to both show and encourage the researcher to think about the motivations behind any change. For vision aid frames, I studied four key design features: the side-arms and form of the frame, weight, adaptations, and materials. The objects were fundamental to my argument, but they were not used in isolation. A variety of sources were incorporated into my analysis in order to fully utilise the object-evidence. Due to the anonymity and scope of the collections, I needed to research additional evidence more widely. For the study of design, I incorporated patents, photographs, advertisements, trade journals, business archives, medical texts, and contemporary discussion in newspaper and periodicals. It was a process of studying the objects, researching relevant evidence, and then re-returning to both the objects and additional evidence. Interchanging different forms of evidence allowed me to explore how vision aids were worn, what vision aids were used for, and the typical users of vision aids. My approach highlights that anonymous objects can be used alongside textual and visual sources to study how and why design changed. However, exploring evidence of wear and how certain designs were used also allows the realities of using – or wearing – an object to be more readily accessed.

To incorporate 1,000+ anonymous objects into my analysis, I spent nine months closely studying each object and documenting significant features, as well as drawing connections between objects within and across each collection. I found that one of the most striking features of a nineteenth-century vision aid collection was the changing form of the frames. The shape of the lenses rapidly reduced in size and the side-arms of the frames rapidly reduced in thickness, even disappearing altogether with the rise in popularity of eyeglasses. Early nineteenth-century spectacle frames are heavy, constructed with thick cold metal, and unwieldy. Late nineteenth-century spectacles frames are supple, light and small. I used this finding as my initial starting point. Focusing on these frames more closely revealed that the side-arms evolved alongside changes to the overall frame. Indeed, it soon became apparent that getting a frame to fit comfortably on the face was one of the most important design challenges for both the producer and the consumer. The material evidence revealed that earlier frames, as shown in Figure 3[17], came with numerous extendable mechanisms – most notably the transverse folding, extending and turn-pin frames – to attach the frame to the face.

However, as can be seen in Figure 4, these mechanisms were eventually replaced by a frame that had flexible enough side-arms that could sit comfortably upon the face, or even rest behind the ear.

There was, however, a disjunct between design continuities and change. Figure 5[18] shows that, for eyeglasses, the frame evolved from the older bow spectacles that perched on the end of the nose to a frame that adopted a spring mechanism and was able to grip the nose and be easily placed on, and removed from, the face – even with a single hand. The continuity in certain designs highlights the subtle ways in which novelty and taste can drive and affect consumer choice. Marina Bianchi, for example, has highlighted the importance of recognisability and exploiting known similarities. Yet this is a delicate balance for, as Bianchi acknowledges, to be new requires the introduction of different characteristics or altering their function (Bianchi, 1998, p 10). For the nineteenth century this was achieved through drawing upon traditional vision aid frame shapes using new materials or by developing innovative ways of affixing them to the face.

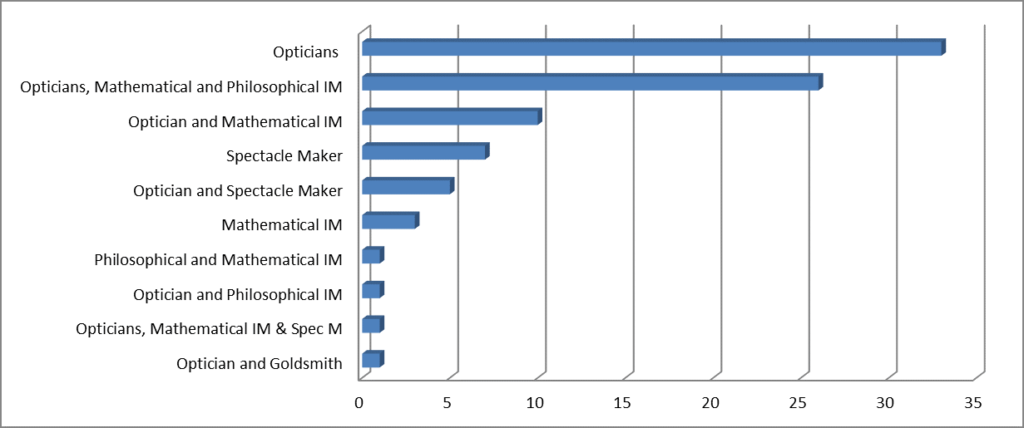

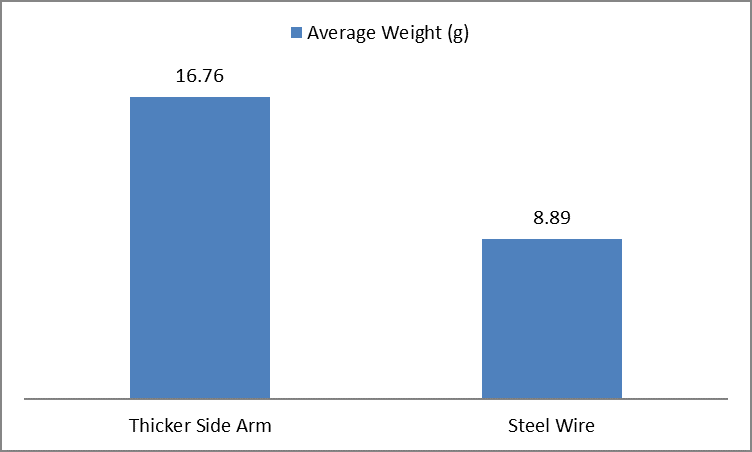

As part of this analysis, I weighed each vision aid frame in the Science Museum’s collection to assess whether the style of frame had an influence on weight. I found that the effect of the vision aid frame on weight was considerable. Figure 6 shows the influence of thinner side-arms on the overall weight of the frame, by more closely analysing the weight of 136 straight wire frames and 204 older sheet casted metal and tortoiseshell designs.

While this does not give a full account – because straight spectacles could be as heavy as 38.33g and the overall weight was also affected by the weight of the lens – it does suggest that the weight of the frame was becoming lighter.

The material evidence derived from exploring the changes in side-arm design highlighted that a number of features were important in promoting and driving changes in vision aid design: weight, the security of fit, and overall comfort. Combining these objects with an analysis of textual sources allowed the motivations and reasons behind the emphasis on weight, security and comfort to be fully explored. Firstly, it is important to note that, similar to prostheses, new vision aid design features were being incorporated in response to broader innovations in manufacture (Faulkner, 2002). The lighter thin steel wire spectacle frame in Figure 4, for example, was influenced by newly patented technology that allowed metal wire to be produced around a cylinder.[19] Yet exploring the advertisements and reviews of new styles of frames revealed that security and weight were not simply an outcome of manufacturing processes. From the 1850s, advertisements highlighted that their frames did not ‘slip from the face’.[20] Weight was also emphasised in a regular column on new inventions in the trade journal, The Optician. In 1893 and 1898 the increased weight of a frame, for example, was considered to be a disadvantage and had prevented frames becoming popular.[21] Moreover, in an overview of various designs in the 1890s, the overall improvement in the design of vision aid frames was placed directly in the context of weight.[22] The objects are able to evidence the reduction in weight that was claimed by opticians at the end of the nineteenth century. However, through the study of additional sources, objects are also able to explain why weight was emphasised and becoming important to nineteenth-century makers, retailers and users. The move towards a more secure fit behind the ears, as can be seen in the changing design of vision aids, allowed spectacles to be worn. Rather than simply rested upon the face, the objects show that a frame was now able to remain fixed upon a person’s face.

The emphasis on weight and security can be seen as part of wider concerns surrounding the comfort of the frame and the expectation that vision aids would be worn for both short and extended periods of time. Combining objects with detailed textual research allowed the connection between changes in design and changes in the nature of vision aid wear to be more firmly connected for the first time. Drawing together the previously used sources – advertisements, contemporary discussions of new frames, opticians’ business records detailing manufacture, and patents – and combining them with contemporary discussion in medical texts, newspapers and periodicals, revealed how the function and purpose of vision aid wear was changing. Exploring advice on spectacle wear in British medical texts, for example, highlighted that spectacles could now accommodate a range of activities, such as running, riding and dancing, without becoming displaced (Carter, 1880, p 254). New designs being reported in The Optician took into account the functionality of spectacles for sporting activities, including playing cricket and tennis.[23] Vision aids were also being used to treat more complex errors of vision. The use of more sophisticated lenses – such as bifocals and cylinders – demanded a more secure fit to ensure that the position of the lenses was precise. Discussion of vision aids in medical texts in the second half of the century placed far greater emphasis on the need for lenses to not be displaced and to sit accurately on the face. Debates over the use of spectacles and eyeglasses amongst medical practitioners, for example, highlighted that the eyeglasses’ ability to be displaced became a decided disadvantage.[24] In doing so, it highlights the trade-off that has been found in the use and design of other assistive devices – such as hearing aids and portable oxygen tanks – between the larger, more visible and functional device and the smaller, less visible and less functional device (McGuire and Carel, 2019). Just as the design improvements illustrated in the Science Museum’s collections were enabling vision aid frames to sit more securely on the face, the expectations and need for vision aid frames to sit more securely on the face was increasing in a range of contemporary popular and medical advice. Only spectacles were considered able to meet this functional ability. Indeed, the objects are able to highlight that security and comfort was becoming important in vision aid design, and textual evidence was able to support these findings and explain why. Improvements in medical diagnosis of the eye, the increasingly recognised utility of vision aids to accommodate a variety of activities, and a need for more long-term wear were equally as important as broader, overall changes in manufacture in influencing overall vision aid design.

However, unlike textual sources, the objects are able to document some of the implications of more long-term wear and provide a greater insight into the wearing experience of vision aids in the nineteenth century. Were changes in vision aid design successful, and were frames more comfortable? The catalogue information was beneficial in this analysis. Frames in Matthew Dunscombe’s earlier and current collection reveal that a number of new designs incorporated additional features to improve the comfort of the frame on the skin or to reduce pressure.[25] Similarly, the use of additional materials to increase the comfort of the frame in Wellcome’s collection is especially illustrative. While a collector of vision aids has noted that pads of ‘felt-like material’ can be found on the inside of some straight side-arms, there is almost no mention in historical or contemporary sources of the existence of soft material to improve frame comfort on early to mid-nineteenth century vision aids (Rosenthal, 1996, p 111).[26] The object cannot tell us whether the adjustments were made by the maker or the wearer. However, it nevertheless reveals something about the realities of spectacle wear that is absent in the surviving written material. Similar to the example shown in Figure 7[27], 41 tortoiseshell spectacles, with straight side-arms, which date mostly from the late eighteenth to mid-nineteenth century, have material still attached to the ring ends or sides of the arms.

Additionally, on one frame, the material had only survived on one arm, and this revealed the serrated marks that could be left when the material had worn away or been removed. These serrated marks can be found on a further 35 tortoiseshell frames, which likely had material attached that has since, through the passage of time or the receipt of damage, disappeared.[28] The number of straight frames with velvet-like additional material suggests that the use of material in this way was a standardised practice, adopted to enhance the frame’s comfort. However, as shown in Figure 8[29], there were also a range of non-standard adornments to frames, which suggests that, similar to other forms of prostheses mentioned in the introduction, users could adapt their frame to improve its comfort on a more individual basis. Importantly, the application of material was not restricted to older frames. Lighter steel wire also had, in some instances, small attachments to increase the frame’s comfort upon the face.

Indeed, patents towards the end of the nineteenth century included the use of additional materials on spectacles and eyeglasses to alleviate discomfort. In particular, the use of India-rubber and rubber tubing in patents for the bridge or side-arms of spectacles to prevent irritation highlights that lighter frames were not necessarily comfortable.[30] While the textual sources document that frames were getting lighter and seemingly better-fitting, the material evidence reveals that at the start and end of the nineteenth century people adapted their frames to increase their comfort.

The materiality of the frame not only gives an insight into how vision aids were worn, it also provides insight into the users of vision aids. The soft materials added onto frames within the collection emphasise that these objects were owned, worn and even personalised. The broken objects become especially important here. More broadly, the usefulness of broken objects in historical work has been recognised. Scientific instruments in various states of disrepair, for example, reveal the historical relationships between the users and the object, as well as how the instrument was defined and perceived (Schaffer, 2011). The broken, used or everyday object is also valuable to the historian. As has been shown in the recent use of material culture in the history of emotions, worn objects provide an insight into their users’ lives and even the possible emotional attachment that they may have had (Downes, Holloway and Randles, 2018, pp 4–5; Bell, 2018, p 34; Hood, 2015, pp 67–72). Figure 9[31] reveals how users or owners of vision aids adapted their frames by carrying out, or paying for, repairs to the side-arms and bridge.

The repair of vision aids raises a number of questions about the cost of the overall frame or the importance of the frame to their user. While anonymous objects cannot give any specific insight into who wore the frame, the material of the frame itself does provide evidence of the cost, and therefore the type of users that would have been able to access or afford vision aids in the nineteenth century. The materials of vision aid frames ranged from cheaper metals, such as steel, to tortoiseshell, silver and gold. These different types of frames were sold for a range of different prices in opticians’ account books and catalogues and their advertisements in newspapers and periodicals. Combining my analysis of the material of the frame with these sources was one of the most illustrative ways of using a broad range of textual evidence to support and tease out the significance of an anonymous collection. The vision aid market was as diverse as the collection proposed. A study of 79 advertisements from a range of locations between 1829 and 1900, based on a key word search of 19th Century British Library Newspapers, revealed how the vision aid market diversified in the nineteenth century. Vision aids did not become straightforwardly more affordable, but the advertisements revealed how the growth of steel spectacles enabled a lower market range to exist.

The growth in cheaper spectacles, sometimes marketed as spectacles for the ‘humbler classes’, further affected the functionality of vision aids.[32] Vision aids were expected to have a solely utilitarian function by the end of the nineteenth century and there were demands that they should be seen as a basic right for the poor to access work. This was not a one-way process of the market influencing the type of consumer because, as shown through theories of consumption, the consumer can influence the extent and range of the market (Bianchi, 1998, p 10). This becomes especially important for explaining the diversity in vision aid design and their meaning to their user or owner. Spectacles were particularly effective at appealing to a diverse range of consumer tastes because of their flexibility and the multiple functions they served for their users, which went beyond their basic functionality. Similar to prostheses being considered ‘tools of class’, vision aids were imbued with meanings of social status in the nineteenth century; they could be a fancy decorative device and a basic frame that served its purpose to improve a person’s vision (Perry, 2002; Mihm, 2002; Turner and Withey, 2014). Therefore, regardless of monetary value, vision aids could be important to the person that owned them. Opticians’ account books revealed that individuals could frequently return to get more expensive, and inexpensive, frames repaired.[33] Indeed, in certain instances, the cost of repeated repairs amounted to the cost of a new frame.[34] In the context of users, the textual evidence brings the objects more to life. A gold vision aid could have been used to infer a purse was ‘well-stored’.[35] A steel vision aid could have provided a person with access to work.[36] A repair could be one of many repairs that a person was willing to undertake on their favourite frame, or a makeshift attempt to avoid the personal expense of a new vision aid. The materiality of the frame – coupled with advertised pricing, opticians’ account books, hospital accounts and charity records – revealed that the users of vision aids diversified in the nineteenth century and there were a range of wearing experiences.

The study of vision aid design from 1000+ anonymous objects was an ambitious undertaking. However, the materiality of the objects – the weight of the frames, the materials used in its manufacture, the design of the side-arms, and the additional materials for repair or comfort – allowed the wearing experience of vision aids in the nineteenth century to be more directly accessed. In showing how design changed, the objects were also able to document why. This approach could have been used on a narrower range of named objects, but a significant proportion of objects for cross-reference and comparison would have been missed. Again, the anonymous objects were particularly useful for documenting a much broader range of vision aid users. The cheaper materials highlight not only a more miscellaneous market of vision aids; the growth of a lower market range and use of cheaper materials can also be connected to the broadening usage of vision aids. Teasing out the reasons behind vision aid design, however, did require a significant amount of labour. ‘Spectacles’ and ‘eyeglasses’ as a whole needed to be searched in nineteenth-century newspapers, periodicals and medical texts rather than focusing on key designs. Additionally, broader categories of ‘opticians’ and ‘spectacles and ‘eyeglasses’ needed to be searched in trade catalogues, accounts and business records rather than focusing on key individuals. While labour intensive, this is not a constraint to research. It allowed the objects to be placed in a much broader context and to explore the multifarious nature of vision aid wear in the nineteenth century. The material evidence was not derived from abstract artefacts that documented key changes in vision aid design, but instead was an insight into the use, wear and a person’s attachment, whether from choice or necessity because of cost, to certain frames. The range of textual and visual source findings revealed what the collections showed at first sight: vision aid design was varied, vision aid use was varied, and the design and use of vision aids was becoming increasingly more complex.

Conclusions

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201306/004Studying the retail and design of vision aids shows how the named and the anonymous objects can be usefully used by historians. The collections, as a whole, have been integral to my analysis and illustrate the value of broad, anonymous collections for historical work. Vision aids, as everyday items, might lend themselves particularly well to an approach that places greater emphasis on the anonymous, broken or utilitarian objects. While this may be the case, valuable findings from anonymous objects and large collections of material evidence can be applied more broadly to historical research. Indeed, the study of vision aid retail highlighted how similar approaches can be used for the study of named and un-named objects. Objects, regardless of the amount of surviving catalogue information, create new historical angles of enquiry. They promote questioning. Focusing on the materiality of the object and additional sources provides new insights and perspectives on historical topics. The change of side-arm would not have featured so prominently and would have left my discussion of vision aid design, and the wearing of vision aids, incomplete. The same could also be said for the use of additional materials and the importance of comfort or repairing a frame, as well as the growth and diversification of vision aid users through a cheaper, more marketable, range. The latter in particular would not have featured so prominently because textual and visual sources were much less visible and largely fragmentary in comparison to the wealth of object-based evidence that remained. Focusing on the cheaper, anonymous vision aids is illustrative of how I have demonstrated that objects are valuable sources of evidence to help answer the questions that they initially promote. As I have shown, the absence as well as the existence of evidence on an object is just as important to the historian.

The ability of objects to promote questioning, open up history and reveal the wearing experiences of vision aids in the nineteenth century is evident when engaging audiences outside of academia. I have used images of the objects at a number of different public events, including the College of Optometrist’s Open House event, the Being Human Festival, and the Swansea Science Festival. While initial audience responses, such as ‘I didn’t think they would look like that’, or, ‘They look like mine today’, might at first seem conversational, they were also profound. They led to deeper questioning, including ‘How did people wear or use that?’, ‘Who owned that frame?’, ‘I wonder what it would have been like to wear them, were they comfortable?’, ‘Were the frames that look like mine viewed as fashionable or stigmatised?’. As people asked these questions the object moved away from being a disconnected historical artefact to a personal object that was owned and worn by somebody in the past. As an historian, I think it is possible to benefit from this process of initial intrigue and then more detailed, focused, and potentially emotional, questioning. Indeed, witnessing these responses made me realise the importance of objects for communicating history. People’s engagement with the objects and questioning could have been taken a step further if I had the objects with me and they were handled. However, I was in a privileged position where I could handle them.[37] In handling the objects, more abstract questioning about the object changed into detailed questioning about the specificities of the object that I was holding: What was its weight? Is there any evidence of wear or use? Is there any evidence of how it was designed, made and sold? Objects not only engage a range of public audiences, they also act as a useful tool for developing and shaping historical work.

Exploring a broad, anonymous collection has revealed the value of collectively studying a large group of objects. This is not without its practical challenges and I recognise the benefits of being a collaborative doctoral student, which gave me unmediated access to two collections over a three-year period. Despite the potential practical hurdles, however, time with the objects should not be completely side-stepped. Handling the objects was a crucial part of the research process that cannot be fully replaced by looking at a photograph, 3D rotating image, or an online catalogue.[38] Additionally, studying a collection as a whole was a thorough way of examining the representativeness of the collection and the objects it held. Tracing, where possible, how and when each object was acquired, as well as drawing connections to a variety of historical sources to determine how it was used, sold and perceived was important in formulating my conclusions about both the individual object and the broader historical questions that I was exploring. Without this collection, or by focusing on only a cross-section of this collection, my findings would have been incomplete and I would have been unable to fully assess the wear and use of vision aids in the nineteenth century. Despite this, my work would have been equally as incomplete if I had relied solely on the objects in lieu of additional sources. Textual and visual sources help us to further interpret why objects changed, why objects looked as they did, or how objects were used. The evidence provided by the objects was enhanced rather than diminished by the use of supplementary sources. Trying to deduce a hierarchy of material, textual and visual sources would be counter-productive. Similarly, trying to deduce a hierarchy of objects as a historical source and disregarding the anonymous in favour of the named is something that creates misleading conclusions and fails to fully utilise the use of material evidence as an historical source. I would argue that an interchange between all types of source develops a more detailed understanding of the wear or use of an object in the past. Using a collection of anonymous, broken, utilitarian, named, elaborate and detailed objects in its entirety is a valuable and essential source for exploring and communicating the history of vision aids and vision testing – and by extension the histories of medicine, science and disability – both academically and to a broad range of audiences.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the two peer reviewers for their encouraging and insightful comments which helped to develop the articulation and significance of my argument and methodology further. As an outcome of a Collaborative Doctoral Partnership between Swansea University and the Science Museum, I am grateful for the funding from the AHRC that made research of this nature possible. I would also like to thank my supervisors from both institutions – Professor David Turner, Professor Louise Miskell, Dr Tim Boon and Stewart Emmens – for their guidance and support in overcoming the challenges of working with a large anonymous collection and helping me to maximise the potential of my research findings.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text