Rapid Response Collecting and the Irish Abortion Referendum

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/20140

Abstract

The last decade in Ireland has seen rapid societal change, including the enshrining of equal marriage and women’s right to bodily autonomy in the constitution via public referendum. In response, the National Museum of Ireland enacted a programme of collecting the material culture of such significant contemporary events in Ireland, which led to the formal establishment of the Contemporary Ireland Collection. The material culture of the referendum on the abolishment of the 8th Amendment of the Irish Constitution (Repeal the 8th) to allow for the legal termination of pregnancy formed the nucleus of the collection, and the rationale behind the identification of the representative themes and subsequent object choices has become the template on which further contemporary collecting is now based. This has enabled the institution and its curators to work collaboratively with the public in the expansion of its collections to fill the historic gaps and become more inclusive and representative of Ireland’s varied and difficult history.

Keywords

abortion, contemporary collecting, contemporary history, difficult histories, Irish constitution, Irish society, National Museum of Ireland, public referenda, Repeal the 8th, Reproductive rights, women’s health

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/The last decade in Ireland has seen rapid societal change, with referendums approving both marriage equality – making Ireland the first country in the world to enshrine same-sex marriage in the constitution by public vote, in 2015 – and, in 2018, the abolishment of the 8th Amendment of the Irish Constitution, to allow for the legal termination of pregnancy. For a country generally regarded as a bastion of Catholicism, and for which Catholicism has been a central pillar of Irish national identity, it is difficult to overstate the significance of these events in contributing to societal change.[1]

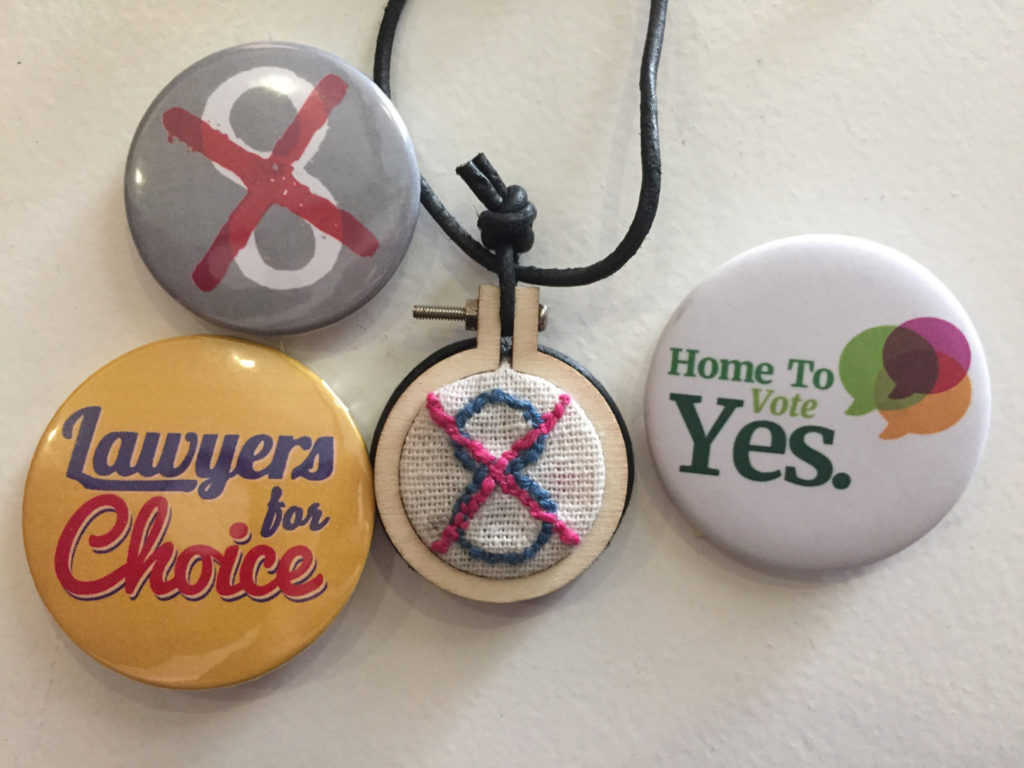

Selection of Repeal the 8th campaign pin badges

© Brenda MaloneIn early 2018, having spent nearly two decades working with the collections at the National Museum of Ireland (NMI), I spoke at a conference about the Museum’s past experiences of contemporary collecting. The NMI was established in 1877 by combining a number of existing institutions holding archaeological, anthropological and natural history collections, and, as Ireland was then part of the British Empire, run as a museum of science and industry under the South Kensington Museum. With the coming of independence in 1922, the NMI began to assert a more Irish identity, primarily in its displays of Celtic art objects, and eventually in new departures in collecting. The material culture of traditional life in Ireland was part of an early contemporary collecting programme from the 1930s onwards by Irish Folklore Commission field work agents who recorded oral histories, photographed craftsmen and women, and commissioned examples of the objects they made in the knowledge that such skills would soon disappear. At the same time participants in the fight for Irish Independence urged the NMI to collect the historical objects and relics of the revolutionary period before they disappeared. This can be regarded as near-contemporary collecting due to the fact that it began within a decade of independence. However, as the state developed, the Museum appeared to unconsciously regard the coming of independence as the culmination of Irish history, and no further collecting in the area of the history of the state occurred.

I ended the paper by underlining the need to be pro-active in collecting the material culture of today’s issues and social movements in order to preserve them in our national narrative and to avoid perpetuating that gap in the nation’s history that now existed.

Some months after this conference I took the post of Curator of Military History, a wide remit encompassing many object types and histories, which coincided with the holding of the referendum on the 8th Amendment. This presented the opportunity to initiate a rapid response collecting programme to record this significant event. This became the NMI’s first real instance of contemporary collecting in the area of history and society for some decades, bar some occasional acquisitions such as a decommissioned AK-47 representing the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and Peace Process, and the sign from the collapsed Anglo-Irish Bank, representing the end of the Celtic Tiger, chosen by public poll in 2013. This paper outlines the collecting schema that was formed to ensure full representation of the event through its material culture, and discusses ten of the object areas chosen to represent its story and how members of the public were involved in their creation and acquisition.

The schema

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/002The inspiration to resurrect contemporary history or rapid response collecting at the NMI drew inspiration from a number of worldwide projects of a similar nature and continues to do so. A major inspiration was the active decision to collect artefacts such as the posters and banners, art and ephemera of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which led to the nationwide collection of protest material that continues today. The New York Historical Society’s ‘History Responds’ collecting programme, begun in response to the 11 September 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, also documents protests through the wealth of material it collects at source by its curators. The People’s History Museum in Manchester, UK, also provided a model for collecting. Since the beginning of collecting at the NMI, museum practitioners across the world have dedicated themselves to collecting material representing issues such as climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic. Knowledge of these museums’ work and their experience of collecting protest objects naturally influenced the thinking around the formulation of a plan to collect Repeal the 8th in Ireland, especially regarding public involvement in sourcing artefacts, and in acknowledging that protest objects across the world have many similarities.

The first step in the collection plan for Repeal the 8th was the creation of a schema – a decision-making framework which was formulated during the months of the debate before the referendum date by examining the various topics and concerns being discussed in the public arena, and familiarising myself with the material being produced as a result. This involved analysing the key messages of the Yes and No campaigns, looking at polling data illustrating the expected gender, generation and rural/urban opinion divides, the artist community response, grassroots organisations and diaspora protest action. This created a guideline from which to identify groups to approach to engage with the collecting project.

The artist banners and the beginnings of the collecting project

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/003The campaign to Repeal the 8th (the 1983 amendment to the Irish Constitution which regulated that the life of the unborn was equal to the life of the pregnant woman) had been ongoing since its insertion. It resurged at times where high-profile cases emerged, illustrating how the amendment damaged women’s health both physically and mentally, and caused death in some cases. This campaign was renewed in 2012 with the case of Savita Halappanavar, who died in an Irish hospital from a septic miscarriage having been denied an abortion due to the fact that the foetus’ heart was still beating. Her death sparked a series of protests and marches calling for the 8th Amendment to be repealed. These marches, like many protests worldwide, were marked by the use of mostly home-made banners. However, one set of banners – those made by the group Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the 8th – stood out due to their striking resemblance to the nineteenth-century trade and guild banners marched on the same streets and currently held in museums in Ireland. It transpired that the similarity was intentional, as the artists had viewed the NMI’s banner collection during their research. It was from this moment that the decision to collect the event through protest banners was made, since in the absence of a policy specifying the collection of contemporary material, this was a continuation of the historical collections. These banners represent a history of protest and the fight for rights in Ireland, therefore providing a connection between the past and the present.

Artists’ Campaign to Repeal the 8th banners, during a Dublin protest march

© Artists' Campaign to Repeal the Eighth AmendmentRepeal the 8th knitted banner

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/004Another repeal banner that came to prominence through social media was a large banner knitted by a Dublin woman using the logo which came to be the symbol of the campaign. This 1600mm x 1600mm banner was knitted over the course of two weeks of almost full-time work and displayed on two wooden ‘knitting needles’ made from wood salvaged from church pews by a friend of the knitter. It was first displayed at a local café and later in the city centre Yes Campaign headquarters. The maker created this banner in response to the original artwork, which was created by the Irish street artist Maser, being removed from its city location. Consisting of a red heart on a blue background, it had been painted on the wall of the Project Arts Centre in Dublin, but removed twice after complaints stating that the centre, which had charitable status, could not carry political messages. After its removal a call was made for more artworks to be made and distributed, with Maser allowing his design to be used by Yes campaigners copyright free. The knitted banner represented an individual act of protest within the broader mass protest, and speaks of the creation, destruction and re-creation of the original artistic expression and its ideals, which could then persist throughout the Repeal debate through the propagation of the logo and what it had come to represent.

The knitted Repeal banner, with its maker Anne Phelan, outside a Dublin café

© Anne PhelanNo Campaign posters

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/005While artistic and creatively designed banners were the hallmark of the Yes Campaign, the No Campaign concentrated on mass producing the professionally printed Corex posters that were hung from lamp posts across the country. These posters were quite extreme; they became known for their use of graphic imagery and carried various strongly worded and, some would argue, misleading statements, such as the time limit on abortions to be introduced if the referendum passed.[2]

Produced by a number of different national organisations which formed part of the No Campaign in Ireland, they often used nationalist and religious rhetoric in their posters, alongside some allegedly internationally funded groups such as The Irish Centre for Bio-Ethical Reform (ICBR).[3] The No posters were the most prominent material culture produced by the No Campaign, making them particularly important to collect in order to represent that side of the debate. Attempts to collect other No Campaign material such as ‘No’ t-shirts and badges (which were few and difficult to source) fell short as public calls on social media platforms failed to persuade No voters to offer their objects. Similarly, private requests to No voters came to nothing. This has left a significant gap in the collection – the inclusion of the average No voter who voted for reasons not represented by the extreme posters – which is to be rectified.

A No Campaign poster incorrectly suggests the proposed legislation would allow free abortion up to six months

© Brenda MaloneA grassroots movement

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/006One of the key characteristics of the Yes Campaign was its grassroots nature. This movement was largely instigated by individuals who were not leaders of organisations or political parties. Whether individuals came together as a group or alone, they were mainly the rank and file of society. Even activist groups such as Lawyers for Choice (who presented the NMI with their own banner) were not the leaders or representative of their whole profession, but were members of its main body. Objects of personal protest include the Rise and Repeal patchwork quilt created by an individual in Cork as a personal response to the barrage of graphic No Campaign posters, especially noticeable around her son’s school, which led to distressing and premature conversations. The creator felt the quilt had a comforting feel to it, which contrasted with the tone of the campaign debates.

The rural/urban divide

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/007Traditionally, referenda results in Ireland could be predicted geographically, with the rural result veering towards the conservative and the urban tending towards the progressive. Data from the referendum on the 8th Amendment showed no real divide (similar to the results of the marriage referendum of 2015). However, the only counties to vote No in either referenda were rural counties. To illustrate this, it became essential to represent these counties in the Museum’s collections. The Roscommon Farmers for Choice sign created by a sheep farming family was chosen to represent the only constituency to vote no to marriage equality, but which voted yes to repealing the 8th Amendment. It is therefore a critical vehicle for talking about changes in social attitudes. It is also an example of the participation of the men who campaigned for partners, family members and friends. Conversely, the Yes Campaign ‘My Body My Choice’ dress, placed onto a mannequin and used as a banner in marches, was created by a yarn-bombing[4] activist in Donegal, and in the Museum collection it represents the only constituency in the 2018 referendum to vote no to repeal.

‘Roscommon Farmers for Yes’ campaign banner, with makers Caroline and Keith Walsh The Donegal yarn-bomber ‘My Body My Choice’ dress, with maker Caroline Kuyper

Art and performance

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/008The art community was heavily involved with the Yes Campaign, and, like the Artist’s Campaign to Repeal the 8th, the Cut-Out Dolls, a performance art group in Limerick, were a visually impactful part of protest marches. The NMI acquired their striking black and white costumes, made in the form of the cut-out paper clothing popular in comic books aimed at young girls in the 1980s, which dressed the bodies of the performers with the numeral ‘8’ while their performances illustrated the negative impact the 8th Amendment had on the lives of Irish women.

The Cut-Out Dolls use performance as an act of protest

© The Cut-Out DollsModern design and pop culture

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/009Another notable banner present at the marches was ‘Uterus Prime’, a design created in late 2016 by a young Irish architect to raise funds for the Abortion Rights Campaign and Together for Yes. The design, based on the pop culture figure Optimus Prime of the Transformers, was also available on t-shirts and jumpers. The creator stated that Prime stood for the integrity and freedom of all sentient beings, and her re-imagined Prime – as a uterus mask with the words ‘Bodily autonomy is the right of all sentient beings’ underneath – transformed the character into a female hero.

The ‘Uterus Prime’ concept and logo was designed by Dublin architect Rae Moore

© Rae MooreReferendum day

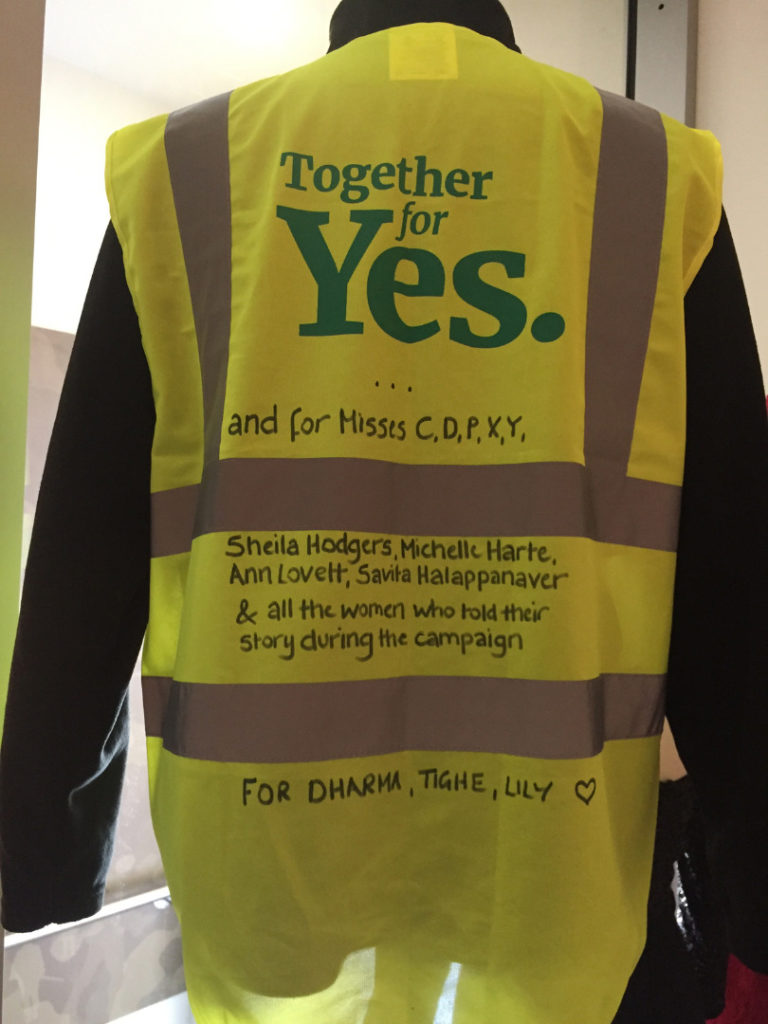

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/010A hi-vis vest worn while canvassing for a Yes vote became the NMI’s representation of the process of the referendum tally, as it was worn by the donor at the counting centre in the South Wicklow constituency the day after the vote. Printed with ‘South Wicklow Together for Yes’, it is also decorated with the handwritten names of women and babies who suffered as a result of the 8th Amendment, bringing the reality of personal loss to the official nature of the object.

‘Together for Yes’ campaign hi-vis vest worn by campaigner at the 2018 ballot count in South Wicklow, decorated with the names of some of the women and children affected by the 8th Amendment

© Brenda MaloneThe Irish diaspora

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/011The most recent generation of the Irish diaspora played a large part in the campaign for reproductive rights abroad, informing emigrants of their voting rights and raising awareness in their adopted countries. One such action was the 2016 London Irish Abortion Rights Protest, when 77 women silently marched with wheeled suitcases to the Irish Embassy in London to represent the 77 women who travelled to Britain per week to access a safe abortion. One of these suitcases was deposited in the NMI by its owner; a physical object to represent both the protest movement and the 77 women who could not otherwise be identified. Alongside this is the hand-made ‘Be My Yes’ sign created by another member of the London-Irish Abortion Rights Campaign. Despite no longer having a vote, she returned to Dublin on the day of the referendum to ask others to vote Yes on her behalf.

77 London-Irish women representing those who have to travel to access abortion lead a silent protest against the 8th Amendment at the Irish Embassy in London Breda Corish campaigns to Repeal the 8th at Dublin Airport as people come home to vote

Personal stories

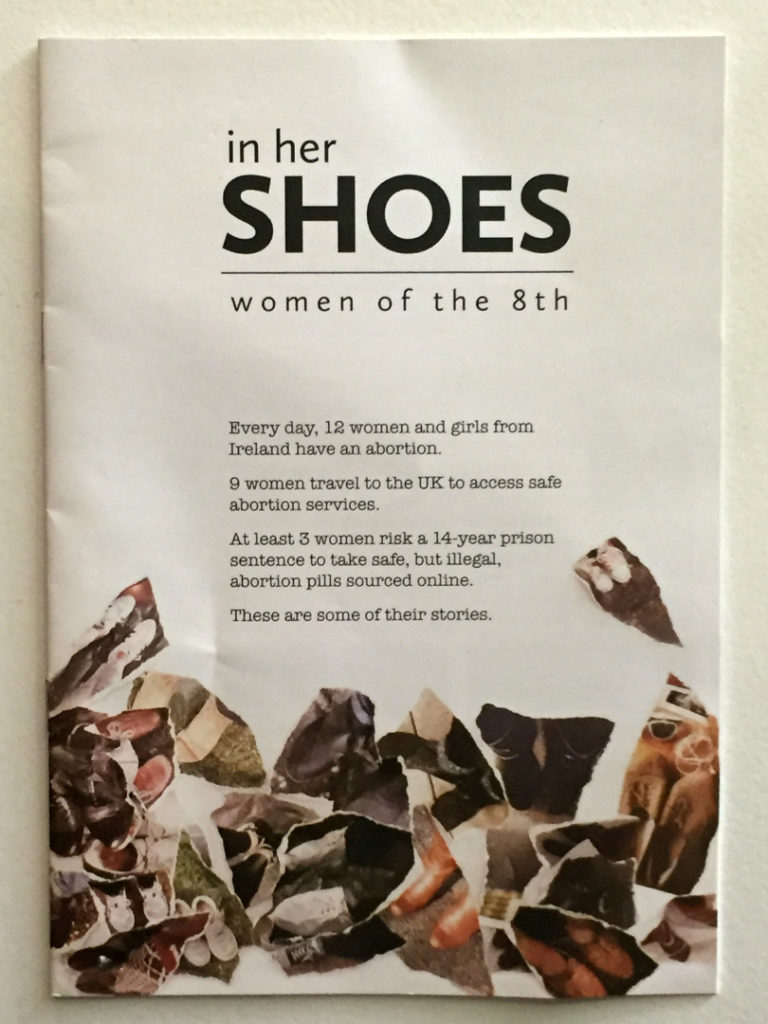

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/012Probably the most influential group of the Repeal campaign was ‘In Her Shoes: Women of the 8th’. The group began as a Facebook community of women who had experienced needing an abortion, for various and complex reasons, in Ireland. Their stories were detailed accounts of their circumstances, emotions and rationale, and were shared across social media with a reach of four million views per week. This gave the wider public a deeper understanding of the multitude of reasons why a woman may need to access an abortion, which led to increased empathy with women who were in this situation. It was compassion which swayed many undecided voters to ultimately vote Yes, and ‘In Her Shoes…’ was a large part of this. So far, the only representation in the NMI of this group is the ‘In her Shoes…’ leaflet, but the publication of a book of 32 stories, representing all counties of the island of Ireland, will be added to the collection upon its release in late 2020.

‘In Her Shoes…’ pamphlet, telling the stories of women affected by the 8th Amendment

© Brenda MaloneConclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/201401/013The acquisition of the Repeal the 8th Amendment material happened very much in collaboration with members of the public who not only gave their objects to the NMI, but presented new ideas and suggestions to the curator by expanding the network of engaged individuals and participants. This led to the acquisition of the first LGBTQI+ representation in the NMI, a rainbow flag used to counter-protest graphic images used by the No Campaign outside hospitals by peacefully covering them up. This, in turn, led to the NMI beginning to collect Irish LGBTQI+ history and formally adopt a Contemporary Collecting policy in 2019 to officially allow all collecting departments of the Museum to grow into new areas and ultimately identify and fill the gaps in the story of post-independence Ireland.[5] This process has been one of learning for curators; to be proactive, collaborative, representative, inclusive, explorative and celebratory where we can be, and honest about our society where we need to be.

Members of protest group Radical Queers Resist covering graphic anti-abortion images with rainbow flags

© Conor KellyTo support this activity it is clear that museums’ management and boards need to support their curators through vision and strategy, the establishment of appropriate collections policies and a commitment to supporting curators moving into new and unknown areas. There is also a need for a firm commitment to properly resource the area in order for the collections of museums, both national and local, to develop with society and remain relevant in this rapidly changing world, remembering that the ownership of our museums is with the public that we serve and represent. The establishment of the NMI’s Contemporary Collecting Strategy enables curators and collectors to confidently reach out to the public for information, conversation and collaborative opportunities, and explore how the future collections of the museum will be formed to represent the many facets of Ireland’s history and its people.

Many thanks to the donors of these artefacts, particularly those who are pictured here.

Tags

Footnotes

https://dublingazette.com/news/news-city-edition/anti-abortion-protest-outrage-icbr/ (accessed 24 November 2020) Back to text