Science and the City: The role of women in the science city: London 1650–1800

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211502

Abstract

Women played fundamental roles in the establishment of London as a ‘science city’ in the period 1650–1800. Taking its inspiration from the themes explored in the Science Museum’s new permanent gallery, Science City 1550–1800: The Linbury Gallery, this paper explores four broad categories of contribution that women made – as scientific instrument makers or retailers, as teachers, as students or participants, and as authors or correspondents in science – to demonstrate that they played more significant roles than has been fully accounted for previously. To do so, we consider the examples of 25 specific individuals and various other virtually unidentifiable women spanning the period 1650–1800. By bringing together examples of different types of contribution, we show that women did not play a single role; they contributed to the emergence of a scientific culture in London in many different ways. All of the women discussed in this paper were individuals with their own reasons for involvement in science. But several factors such as contemporary perceptions of women, networks in London, and the growing demand for scientific knowledge united them all and influenced their experiences.

Keywords

instrument makers, London, scientific instruments, Women

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/A man of sense only trifles with them [women]…but he neither consults them about, nor trusts them with, serious matters.

Earl of Chesterfield, Letters to his son, 1748

Women to possess understandings of ‘masculine strength’, is an idea intolerable to most men bred up amongst each other in the proud confines of a Colleger. There indeed they seem to monopolize learning, but happily intellect cannot be confined there; and as general education increases, Scholars will more & more discover to the confusion of their pride, that genius is shower’d down on heads, as seemeth to Heaven good, whether drest in caps of gauze or velvet – in large grey wiggs, or small silk bonnets…[1]

Mary Knowles, 1783

Women played fundamental roles in the development of London as a ‘science city’ in the period 1650–1800, but, unlike their male counterparts, tracing them in the historical record, archive or indeed the surviving material culture can be challenging. The main, but by no means straightforward explanation for this situation lies with attitudes towards women and the subsequent lack of historical evidence that these attitudes produced (or did not produce). The two comments above, made by the Earl of Chesterfield and Mary Knowles, summarise both the attitude of many men towards women’s intellectual capabilities (or lack of in their view) and the growing frustration felt by many women towards these opinions and the barriers that some men put in the way of those seeking to pursue their scholarly interests. Science City 1550–1800: The Linbury Gallery[2] explores the emergence of a culture of science in London in the early modern period. Embedded within this was the establishment of an instrument-making trade and the growth of learned societies and publications dedicated to natural philosophy. Craftsmen, booksellers, natural philosophers and London’s wealthy citizens were intertwined in a network of early science and women were a significant part of this.

London’s position as the capital city, seat of government, home to the royal court and major port also provided a market for scientific instruments in the broadest sense. Government activity, such as the levying of excise duty on alcohol and warfare, notably gunnery, all required appropriate measuring instruments. Mathematical practitioners, especially those assigned to state-supported projects, were heavily concentrated in London and many of them needed to make precise measurements and observations, including for architecture, assaying, navigation and surveying. Telescopes, invented early in the seventeenth century, were used both by astronomers and by seamen and soldiers. These developments left behind a rich material culture of instruments, equipment, books and art works – examples of which are displayed in Science City. The gallery narrative celebrates the contribution made by different types of people – from instrument makers to natural philosophers and from merchants to the royal family. As a set, the objects on display are indicative of the surviving material record as a whole. The display is strong in terms of its representation of the development of the scientific instrument-making trade in London and the written account of discussions concerning natural philosophy and practical mathematics, but the image it creates is not quite complete. Its incompleteness arises not from a lack of curation, but from the fact that with the vast majority of instruments, only the male contribution to the narrative is visible. This does not mean that the female contribution is not there, but it is often invisible. This paper seeks to rectify this problem, if only in part.

The reasons why women are not as visible as men in the material record of early science in London is mostly due to the wider context of how women were perceived in society and the roles they were permitted (or not permitted) to play. Yet women were integral to the emergence of science in London and there are glimpses of this provided by objects on display in the gallery. One example is a sundial made by Thomas Gemini[3], who claimed to have lived in England thanks to the graciousness of Queen Elizabeth I, who encouraged instrument makers to move to London from the large instrument-making centres in Europe to pass on their skills to London’s craftsmen. Another is Robert Hooke’s Micrographia of 1665, which was criticised by Margaret Cavendish, who was the first woman to visit the Royal Society. However, there is much more to be said and to do so this paper takes its inspiration from Science City, but is not limited to it.

Writing more gender-inclusive histories is not a new endeavour of course. Eğer (2010, p 3) refers to the collective push by historians of gender to make women in history visible. She acknowledges a two-pronged approach in the work of modern writers that sees them correcting previous omissions and also using new research methods to acknowledge women as a distinct social category. While this is a worthwhile aim, this paper does not attempt to suggest that female contributors to early modern science were their own category. Instead, we shine a spotlight on lesser known and unrecorded women and call for more inclusive histories to be developed where women’s contributions are considered along with those made by men, as part of a rich and diverse network of people, rather than in isolation.

The work of Fara (2004; 2005), Ogilvie (2004) and others (Wallwork and Salzman, 2011; Sarasohn, 2010; Roos, 2019; Marschner et al, 2017; Eğer, 2010; Hannan, 2016; Lloyd Edmondson, 2019) has laid the groundwork for our understanding of the roles played by women in the emergence of science in London by identifying the experiences of individuals such as Margaret Cavendish, the Lister sisters, the Georgian princesses, Mary Wollstonecraft, and the Bluestockings. Moving the discussion forward, this paper considers the nature of a contribution in itself and uses the examples of several women to do so. As is well known, women were unable to hold the same positions as men or partake of the full range of science-related activities at this time, so instead of looking for female equivalents beyond those who have already been identified, such as Caroline Herschel, we have to look elsewhere to find them. Young women who were educated in the home, widows of scientific instrument makers who continued their husband’s business, and subscribers to science publications are just some examples that have been traditionally overlooked. By using these examples to put forward a redefinition of a contribution, this paper hopes to inspire further research.

Taking a slightly narrower timeframe than the gallery narrative, our methodological approach in this paper is to divide our discussion into the types of science activity that fed into making London a ‘science city’ in this period, and which were contributed to by men also, and use these to shine a spotlight on previously overlooked women by rethinking the nature of a contribution and thus expanding the network of contributors. We take a case-study approach to consider the roles played by ten individuals with reference to groups of others where appropriate, divided between our three types of science activity: instrument making; educating; and studying/participating. These women either lived in London or were facilitated in their contribution to natural philosophy by people in London. These women have been chosen because the role they played/contribution they made adds something specific to our understanding of the wider contribution made by women, alongside men, to early science in the period. We refer to individuals by both their first and surnames in the first instance and then subsequently by their first names to be clear that we are talking about the women, rather than their husbands. This is particularly important when the husband is a famous name and for consistency we treat each individual in the same way (male or female). As a gesture to the Science City gallery, where possible we identify instruments that the individuals in our case studies may have contributed to making, may have used, or may have been taught with. We combine this with references to surviving archival material, especially Livery Company records, and refer to the wider context to explain the significance of our findings.

Due to the nature of the surviving evidence, the number of examples cited in each section varies, but in the instances where there are few even a small amount of information must be brought to the fore if we are to improve our understanding of the range of contributions made by women. The lack of coverage in the secondary literature of the roles played by women is indicative of the lack of evidence and some historians may have shied away from the topic for this very reason, but by highlighting a lack of evidence we are able to indicate how under-recorded women were and how silences in the archives often speak volumes.

Women as makers and retailers

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211502/002One reason why evidence about the role of women in the making of scientific instruments, which is the discussion that we will now turn to, is sparse is that much of their involvement was connected, at least initially, with the work of their husbands, fathers or brothers. The instrument trade was a craft industry right up to 1800. There were a small number of large workshops towards the end of the period under review, but most instruments were produced by craftsmen and their families, often assisted by a few apprentices and paid employees. The family usually lived on the premises, which made it easier for the women to become involved.

Women played an active role in the making and retailing of instruments and therefore contributed to the supply of devices and apparatus from London to individuals and organisations within the city and beyond. Those women who were most visible in the instrument trades were widows who carried on their late husband’s business. This is well known to historians and was not unique to the instrument trade. It was a common practice in other crafts and Fullwood and Allnutt (2019) have begun to fully explore this in the clock and watchmaking trade, revealing hitherto unfamiliar names of active female clockmakers and watchmakers in the period. Yet the extent of their involvement in the day-to-day running of the business, both before and after their husband’s death in the period 1650–1800 specifically has not been fully explored before. This apparent gap in the historical record is probably the result of a lack of supporting evidence. In fact, as this paper will show, records such as newspaper advertisements, financial records and entries in trade directories show that widows often continued to use their husband’s name on instruments produced in the workshop. While the widows may be invisible in the material record, the dates of the associated archival material and of their husband’s death reveals their presence and thus contribution.

Fara (2005, p 48) claims that the role of women in the family business was not merely participatory, but powerful in that they were involved in all aspects of the business, both learning how to make instruments and supervising financial transactions. Their involvement was not casual; many lived and breathed the craft. Some girls were taken on as apprentices or were trained by their fathers. As young adults, they often married the owners of other shops and then took them over when their husband died, indicating their key contribution to craft networks.

Clifton (1995) has so far traced the names of 58 women who worked in London during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as sellers or makers of scientific instruments in the broadest sense, ranging from mathematical instrument makers to lens grinders and scale and weight makers. In that which follows, we consider the examples of female instrument makers, who were based in London, each of whom is significant in her own way as a representative of the contribution made by women as craftspeople within a male-dominated trade. Following on from these individuals, we consider the existence of women as component-makers to the trade, who were an important link in the supply chain, many of whom are nameless or referred to in single entries in guild records.

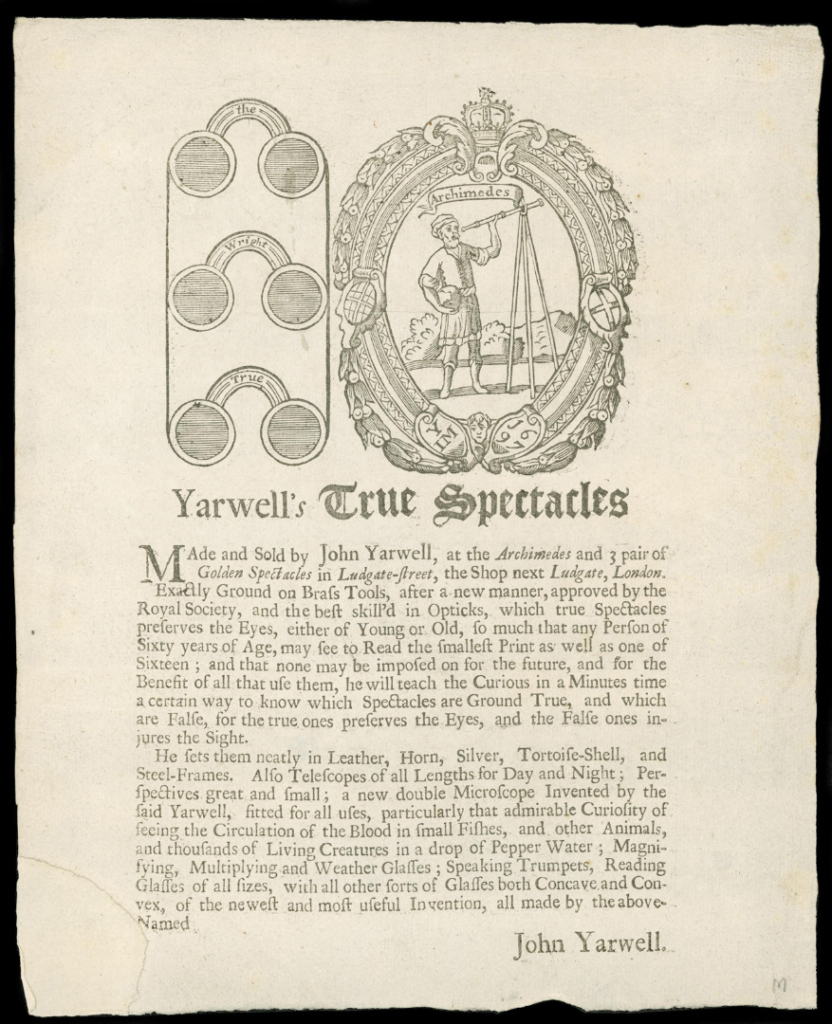

We begin our exploration of women as instrument makers with Mary Edwards. Mary was married to the spectacle maker, Richard Edwards. She took on his apprentice, John Yarwell, when Richard died in late 1667 or early 1668. Yarwell would become one of the leading optical instrument makers in London in the late-seventeenth century. In April 1668, Mary applied to the Worshipful Company of Spectaclemakers, the guild governing the optical-instrument making trade in the City, to take an additional apprentice, but this was refused as John still had 21 months of his apprenticeship to serve, having been indentured in December 1662. Mary continued to pay quarterly fees to the Company during 1668 but then turned John over to Nicholas Shield to complete his training. Though not formally admitted to the Company, widows like Mary acted as Freeman in practice and were accepted as such by members, paying Company fees and taking on apprentices.[4] As with most of the women discussed in this paper, little else is known about Mary, but her example sheds light on the relationship of women with the guilds in the seventeenth century. They were tolerated and accepted by the guilds, who recognised that the trade needed them, even if they were not fully inaugurated.

Jane Hayes was married to Walter Hayes, a mathematical instrument maker whose workshop was located at the sign of the cross daggers in Moorfields. Walter was a member of two London guilds, the Worshipful Company of Grocers and the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. He died in late 1687 or early 1688, leaving the bulk of his estate to Jane, who continued the family business as Mary Edwards had done some twenty years earlier.

Jane, like Mary Edwards, seems to have taken on her late husband’s apprentices. While there is no formal record of this in either the Grocers’ or Clockmakers’ records, the dates for Edmund Culpeper’s training seem to fit this suggestion. Edmund, who would become one of London’s leading mathematical and optical instrument makers, began his seven-year apprenticeship with Walter in 1684. This would take his completion date to around 1691, indicating that following Walter’s death he completed his training under Jane’s management from at least 1688 to 1691. Unlike the Spectaclemakers whom Mary served, it would appear that the Grocers’ Company did not object to a woman formally training an apprentice.

Nearly a decade after Walter’s death, Jane is known to have supplied mathematical instruments to Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School in 1696 and 1697, but presumably passed the day-to-day running of the shop in Moorfields shortly after this to Edmund, who was recorded as trading at that address by 1700. However, it is noteworthy that Jane seems to have retained ownership of the business making mathematical instruments, for when she died in 1710 she left a detailed will in which her address was still given as Moorfields and she bequeathed to: ‘Mr Edmond Culpeper my late servant all my Shop Goods and Tools and Loadstone belonging to the Trade of a Mathematical Instrument Maker and also all my Mathematical Books and the Copy of Gunters Quadrant Book.’[5]

Jane’s example shows a slightly different relationship between a seventeenth-century woman and the City guilds, indicative of how the latter managed their trade slightly differently. It also shows us a little about the experience of women within the craft, whom they supplied and how they chose to manage or divide the business.

Mary Senex was married to the highly-successful globe maker, John Senex, and took over his business when he died in 1740. Unlike the majority of widows in a similar position who sold their businesses after a year or so, Mary, similarly to Jane Hayes over 40 years earlier, ran hers for 15 years (Clifton, 1995, p 248).

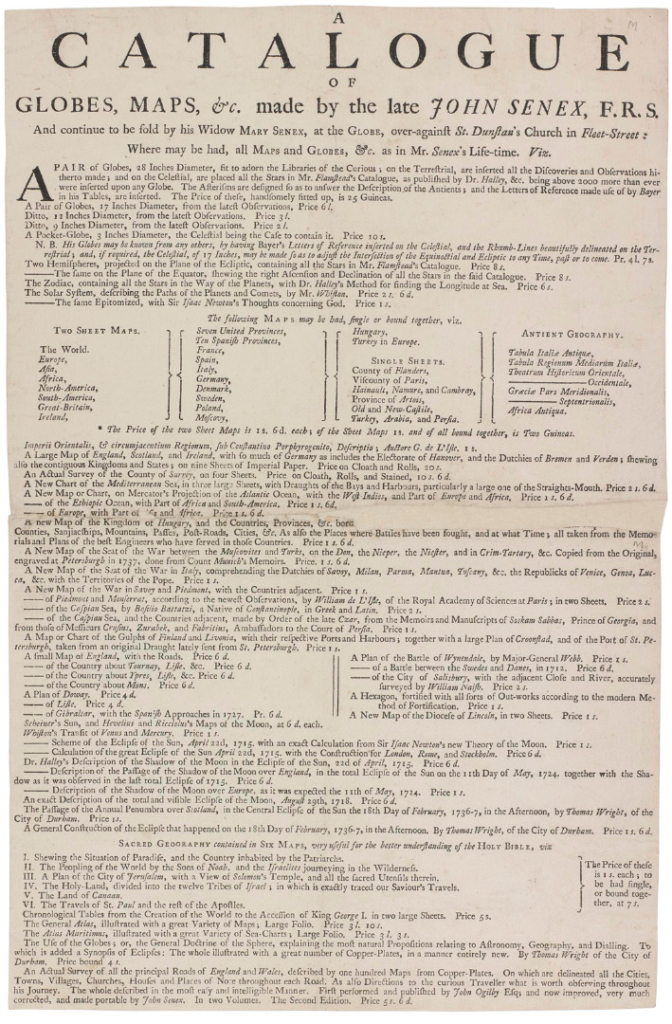

Like Jane, Mary also supplied instruments, but in her case globes, to Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School. This was clearly an important client and one that several widows were keen to maintain. What makes Mary stand out from the other widows considered here was her talent for marketing and protecting her concerns. Mary advertised her instruments in catalogues such as that seen in Figure 4. While it is very likely that she helped to make many globes that bear John’s signature, a pair have been positively identified that were made after John’s death and must have been made by Mary or at the very least under her direction (see Figure 5). As mentioned above, it was common for widowed makers to continue to use their husband’s signature on the instruments they sold – acting as a form of continuity and consequently a source of trustworthiness for customers, many of whom would probably have doubted its quality had they known a woman made it. Besides routinely advertising through trade cards and catalogues[6], Mary actively promoted the globes and other goods she sold. In 1749 she became concerned about competition from imported globes and wrote to the Royal Society pointing out that her late husband’s globes, which she sold, were more accurate than their foreign competitors. Her letter was published in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions.[7]

Mary eventually sold the copper plates for making all of the globes (except the three-inch variety) to the natural philosophy lecturer James Ferguson in 1755, and they were later sold to fellow lecturer and instrument-maker Benjamin Martin in 1757 (Dekker, p 332). This is indicative of how valuable the plates were, not only financially, but in terms of the knowledge they contained and the extent to which this could be transformed into a successful commercial product. It is no wonder that Mary continued the family business for as long as she did. She provides us with a powerful example of a female instrument maker who not only continued the family business, but who brought her own personality to its operation – fighting for it in many corners.

Ann and Hannah Adams, the wives of the hugely successful George Adams the Elder and George the Younger, provide us with a significant example of not only widows who continued the business of their husbands, but also a representation of women who had to possess good business nous – not unlike Mary Senex – who had the capability to act quickly when their husbands died and who were compelled to consider the wider family network when they made decisions. These were not wives who were out of touch with the business and the market, but highly engaged members of a family concern who knew how to respond to different challenges.

Ann was the second wife of George Adams the Elder and the mother of George the Younger. While no evidence exists of her having made instruments while her husband was alive, it is very likely that she did. This seems plausible given that, as Millburn (1976, p 161) informs us, only days after her husband’s funeral in October 1772 and when her son, George the Younger, had only very recently completed his apprenticeship, she placed this advertisement in at least three London newspapers (the Daily Advertiser, the Gazetteer and the New Daily Advertiser):

ANN and GEORGE ADAMS, Mathematical Instruments Makers to his Majesty, &c., at Tycho Brahe’s Head, No.60, in Fleet Street, beg leave to acquaint the Nobility, Gentry, Merchants, and others, that they continue to carry on the business of the late Mr Adams, in the Mathematical, Philosophical, and Optical branches, as in his lifetime, and humbly solicit the continuance of their former favours. Those gentlemen and ladies who honour us with their custom, may depend on their orders being executed with the utmost fidelity, accuracy, and dispatch. Of whom may be had all sorts of instruments in the various sciences of the Mathematics, Philosophy, Astronomy, Geography, Geometry, Drawing, Surveying, Navigation, &c. each of the most perfect construction, and at the most reasonable rates.[8]

Not only was Ann quick to strategically place her advertisement, which was intended to act as both a sign of trustworthiness and a call for further orders, but she also ensured that the practical work was carried out. Millburn (1976, p 161) informs us that ledgers indicate that the business continued to supply instruments to Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School in this period, similarly to Jane Hayes and Mary Senex several decades earlier. It is likely that Ann did undertake some of the practical work. One microscope that was recently sold at auction[9] bears the signature ‘A & G Adams’, which may be the only surviving example from this period in the history of the business and the only one to bear Ann’s signature. Ann also tried to secure the continuation of the Ordnance Office contract, but was not successful. Before George’s will was proved, rival instrument maker Jeremiah Sisson had petitioned for the appointment to be passed to him and was awarded it. This demonstrates how competitive the market was and how widows needed an aptitude for business to be able to keep afloat. The Adams family managed to re-attain the contract by the late 1770s due to Jeremiah’s bankruptcy in 1775.

In 1774, George Adams the Younger married Hannah and the era of the Adams’ mother-and-son partnership presumably came to an end. However, Ann’s influence did not entirely end there. She ensured that her youngest son, Dudley, had an income. The details of the elder George’s will meant that his holdings were legally Ann’s to do with as she pleased. Of course, anything that was the younger George’s was his, but Ann made the deliberate decision to safeguard Dudley’s interests by giving him his father’s globe making equipment so that he could set up on his own at Charing Cross after the completion of his apprenticeship to his brother.

Hannah was as shrewd as Ann and when her own husband George the Younger died in 1795, she acted as quickly as her mother-in-law had done some 23 years earlier. Within a fortnight she had been appointed mathematical instrument maker to the King, continuing her late husband’s endorsement. Similarly to Ann, it is likely that she helped to physically make instruments. Millburn (1976, p 265) informs us that a barometer has survived which bears her signature, although its present location is unknown.

The example of Hannah Adams is a noteworthy one. Apart from being a widow who continued the family business, as many other women did in this period, her experience is different simply because of the surviving family members — her mother-in-law Ann and her brother-in-law Dudley. George the Younger’s will left the business on Fleet Street, his stocks, copyright of his books and shares in various properties to Hannah. This might seem simple enough, but uncertainty remained concerning those elements that were not strictly speaking the legal property of the younger George. This was because everything that had been George the Elder’s on his death was still under Ann’s management and her interests surely lay with Dudley, whom she may have hoped would marry and continue the family line, rather than with the childless Hannah.

It is unknown whether Hannah clashed with Ann, but she certainly did with Dudley. Following the younger George’s death, they both wrote to the Office of Ordnance asking to take over George’s appointment as instrument supplier. Dudley was granted the contract, but lost it in 1806. Despite this setback, Hannah continued to supply Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School, which Dudley did not challenge her for. Perhaps to raise some funds, she decided to sell the library at Fleet Street in 1796, which contained approximately 2,000 volumes. Dudley later remarked that he had felt vexed by this. While he did not act to halt the sale, his comments indicate that he was not on the best of terms with his sister-in-law. The relationships between individuals within an instrument-making family were clearly as significant for the supply chain as those between makers within the wider network.

Sarah Ramsden, the only one of the seven women considered in this section whose maiden name is known, grew up in an instrument-making household of high repute. Her father was John Dollond, celebrated as the inventor of the achromatic lens. At the age of 23 Sarah married Jesse Ramsden, who was a neighbour of the Dollonds and dined with them in the early days of his career. Far from unusual, it was noted above that many daughters of instrument makers went on to marry other instrument makers and this was often a strategic move to expand immediate networks.

During her marriage to Jesse, we know that she helped with the physical aspects of the craft (McConnell, 2007, p 23). Referring to Jesse’s first dividing engine, which was sent to France in 1775, a Jean Hyacinthe de Magellan commented in a letter to a Mr Mallet that even Jesse’s wife operated it: ‘…cette machine dans laquelle travaillaient les élèves et meme quelque fois la femme de Ramsden.’ (‘This machine on which students worked and sometimes even Ramsden’s wife.’)[10] In the context of this period, the reference was used to demonstrate how easy the machine was to operate rather than as praise to Sarah, given that the reference to her followed that to his apprentices. While the dividing engine may indeed have been easy to operate, given her background, it is more than likely that Sarah was involved in many more aspects of the craft than was recorded or has survived.

We get a glimpse of this from what we know of her life once she separated from Jesse. This unusual situation for its time provides us with a valuable insight into the part played by women in the rise of the instrument-making trade and is slightly different from the other examples discussed here of widows who continued the family business after their husbands died. The reason behind the separation is unknown, but may have had something to do with the falling out between her father, John, and Jesse over the achromatic lens patent. Whatever the cause, we know that Sarah was living separately from Jesse, and crucially with their son John, certainly by 1786, but probably by 1784. In the years that followed, Sarah acted as a retailer, or middleman, between Giuseppe Poli and Matthew Boulton – corresponding with the latter in order to supply a steam engine to the former (McConnell, 2007, p 251). We know that Sarah acted as broker for Giuseppe for other supplies – he wrote to Joseph Banks on 2 March 1784 asking Joseph to pass a medal to Mrs Ramsden who would make the payment for him. Aside from her own work, we know that she also assisted her brothers with their optical work in this period – both their practical work and their accounts. The example of Sarah gives us an indication of the role played by female members of the family business in its running even when the men were still alive. Returning to help her brothers after the collapse of her marriage gives us an unusual insight into the probable role played by unmarried sisters and daughters within other workshops.

The contribution of some women is only visible in short references within the archives of the City Livery Companies. One of the purposes of trade guilds was to regulate the standard of goods produced and maintain the reputation of their craft. In order to do so, senior figures carried out searches in the City of London and seized faulty goods, not just from guild members but also from others making or selling items which came under a particular guild’s supervision. They also sought to ensure that all apprentices had been properly bound through the guild. Some of the records of these searches reveal women’s involvement in making scientific instruments, or indeed their components, such as lenses. The Spectaclemakers’ Company records include a detailed account of a search made on 16 September 1670. It reported that in Bishopsgate they searched the premises of Mrs Jenkinson, where they found nothing worthy of comment, but at ‘Widdow Cosby, Spectaclemaker one bad paire rased’. A little earlier, in 1668, John Cosby was bound apprentice to Alice Cosby, ‘widdow and his Mother a Spectaclemaker’, so clearly she ran the business for a while and may have been minding it until her son was old enough to take over. At another search, in 1691, at Ralph Harbottle’s house in Deane Street, the Company’s representatives ‘found John Harbottle his Son at Worke grinding Glasses for Spectacles alsoe a Woman grinding at another Toole…’.[11]

Some spectacle-lens grinders also produced lenses for telescopes and microscopes. Occasionally, women were apprenticed to instrument makers. For instance, in 1737 Susannah Passavant became the apprentice of George Willdey, optical instrument maker, and was later made a Freeman of the Spectaclemakers’ Company. She eventually had her own ‘Toy Shop’, which in the eighteenth century usually sold pocket telescopes (polemoscopes) for use at the theatre, as well as other small decorative items, as indicated by a trade card in the Heal Collection at the British Museum. She continued to pay the customary quarterly fees to the Spectaclemakers’ Company until 1761.[12]

The Clockmakers’ Company claimed authority over mathematical instrument makers, who made all kinds of measuring instruments, including rules and sundials. They too conducted searches to check that their regulations were followed and that the quality of the instruments was satisfactory. During a search on 21 February 1671/2, they seized from Mr Charles Danley, a seller of canes in Fleet Street, ‘two sundialls for posts, affirmed by him made or sold to him by Widow Cator’.[13]

While references to the female component makers may appear small and insignificant, they represent a larger issue. Firstly, that these workers were not considered important enough to record unless they represented a problem to the trade. Secondly, while effectively nameless, their contribution to the trade was huge. Large numbers of instruments would not have been produced so quickly – which enabled the London trade to become one of global significance – without their work, which means their contribution was fundamental.

In this section we have seen that female craftspeople made a very real contribution to the growth of the instrument-making trade in London in the period. The trade may have been dominated by men, but its functioning, success and survival were very much the results of a collaborative effort despite the fact that most women were unacknowledged formally, which was due to the perceived role of women in society and business more generally. We have shown that where widows continued their husband’s business, it was not a simple matter of continuing to open the doors every day and keeping a record of orders; it took a lot of hard work and strategic thinking to maintain a successful business in this very competitive market. By considering the six individuals above, it has become clear that there were several core business activities that they carried out (the same as their late husbands would have done and male counterparts in the wider network did). They maintained existing contracts, which Jane Hayes, Mary Senex and Hannah Adams did with Christ’s Hospital Mathematical School. It was beneficial to keep training existing apprentices and to take on new ones, as we saw Mary Edwards try to do with John Yarwell and Jane Hayes with her late husband’s apprentices. Securing new customers and contracts was essential. Each of the women considered here provide a good example of maintaining existing contracts. Sarah Ramsden provides a particularly insightful example of women securing new work in her role as a supply agent working between Giuseppe Poli on the one hand and Matthew Boulton and Joseph Banks on the other. Advertising was another essential aspect of their work. We saw how Mary Senex made effective use of trade cards and both Ann and Hannah Adams used newspaper advertisements to their advantage. Operating in a city where businesses went bankrupt or were outperformed by others required our individuals, both men and women alike, to protect their concerns. We saw strong examples of this with Mary Senex who wrote to the Royal Society about her concerns and Ann and Hannah Adams who each acted quickly and strategically after their husband’s death. A significant ingredient that made all of the above easier was the ability to network both within the trade and outside. Mary Edwards provides a good example of a widow who made use of her guild network – acting as a Freeman in practice even though she was not admitted. Mary Senex and Sarah Ramsden made use of their contacts at the Royal Society. And the component makers made use of the networks to supply to as many workshops as possible, which in turn enabled the existence and growth of the overall network.

Women as educators

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211502/003Women contributed to the provision of early science teaching in London through public lectures and private schooling. As with the instrument-making trade, science teaching was predominantly a male undertaking, and the involvement of women in this context has not been adequately acknowledged in the traditional historiography. By ‘adequately’ I mean that their role has not been explicitly stated, which it must be if a more accurate history of early science in London is to be conveyed – if we always only mention the people that we know more about, in this case men such as John Theophilus Desaguliers, then the contributions of others, such as women, are assumed to have not existed, which is of course inaccurate. By writing an entry for Margaret Bryan for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Ogilvie (2004) has opened the discussion of women as natural philosophy educators in this period. While representation of Margaret in a resource such as this is valuable in terms of capturing information about her, it will only be found if a researcher searches for her specifically. The significance of Margaret’s contribution can only be fully appreciated if it is brought into a wider discussion of the other contributions made by women (alongside men) to science activities in London at this time. In that which follows, we consider both her and another example of a woman who contributed both to the sharing of natural philosophical knowledge in London and to the use of instruments for pedagogic purposes.

In the early eighteenth century, Mary Hauksbee facilitated science teaching by enabling John Theophilus Desaguliers to continue her late husband Francis Hauksbee the Elder’s lecture series after his death. Francis had been an instrument maker and lecturer on natural philosophy, providing classes/sessions at his premises near Fleet Street (and demonstrating experiments at the Royal Society). The nature of Mary’s enablement was that she permitted John to use her premises, which we know from advertisements took place at the home of ‘widow Hauksbee’ at the upper end of Hind Court (Wigelsworth, 2010, p 58), and presumably to use her late husband’s teaching materials and instruments, which we can infer from the speed at which John took them on. This happened, perhaps too quickly, because the combined venture did not prosper and John began working alone. In providing this continuation of her late husband’s work, similarly to the female instrument makers considered above, Mary contributed to the formal imparting of knowledge to others. For this reason and in this social context, where it was not considered acceptable for women to work as lecturers in the same way as men, her contribution as an enabler of education must be acknowledged.

Mary is a slightly unusual example because although, like many other women, she continued to work after her husband died, what makes her different is that in the longer term she did so in his original craft, drapery, and not instrument making or lecturing. By 1714, just a year after Francis’ death, she had moved from Hind Court to an alms house and returned to drapery – binding three apprentices, including her son Calvin. Francis was originally apprenticed as a draper to his brother, John, and became a Freeman of the Drapers’ Company of London in 1712.[14] It is not known how he made the transition to making philosophical instruments. However, given that after his death Mary eventually returned to the drapery business and took apprentices in that trade, it is very probable that she had also worked in that craft during the early years of her marriage to Francis and possibly earlier in her father’s household, but later became involved in instrument making and continued his business for a short time.

Little else is known about Mary, but this lack of further evidence which could inform us about her life once she returned to drapery is itself indicative of the lack of opportunities for women that were equal to those available to men – after all, John Theophilus Desaguliers, by contrast, went on to become an immensely successful public lecturer and had circumstances been different, Mary might have done so too. Furthermore, the lack of documentary evidence for Mary helps us to rethink the nature of a contribution. In this particular context, where women were not generally documented in the same way as men, smaller pieces of evidence relating to them must be considered differently to equivalents referring to men – they must carry more weight. Rather than looking at an advertisement that mentions Mary’s premises and dismissing it as unhelpful in contrast to the multitude of advertisements, published pamphlets and articles referring to John, as traditional histories have done, we must use it to rethink the nature of a contribution which in some way helps to redress the balance.

While there do not appear to be records of other women teaching science in London during the early eighteenth century, some 82 years after Mary Hauksbee facilitated the continuation of her late husband’s natural philosophy lectures, Margaret Bryan was operating her own schools and teaching mathematics and natural philosophy to girls and young women. We know much about the educational establishments in the city managed by men and created for teaching mathematics and natural philosophy to prepare young men and boys for work in this period. Examples include the Hand & Pen in St Paul’s Churchyard and The Academy on Little Tower Street among others (Stewart, 1992, 114; 146), where tutors also lectured in the city’s coffee houses, but less has been said about opportunities for young women and girls or female educators. These opportunities may have been considerably less than those available to men, but this is not to say that they were non-existent. And it is this point that needs to be brought home. While some women throughout the period learned from relatives or visiting-tutors in their homes, which is discussed in more detail in the next section, the example of Margaret indicates that others attended schools set up for teaching young women and in the context of science teaching this was new in the late eighteenth century.

For Ogilvie (2004), Margaret was a noted early example of a woman who taught natural philosophy to young women and girls, but she is more significant than that. What distinguishes her from others was that, as far as we know, she was the first woman to do so in a formal capacity that took place outside of the home. Not limited to one location, she ran a boarding-school for girls at Blackheath from 1795 to 1806, opened a school in London in 1815, and moved to Margate in 1816, where she also ran a school. The curriculum in her schools differed from that of most of the other institutions for women by including mathematics and science as suitable subjects for girls. This is significant within a context of science teaching that was primarily conducted by lecturers who taught at coffee houses and private schools such as the Hand & Pen and The Academy, none of which were open to women – as teachers or students. Moreover, whereas at the beginning of the eighteenth century Mary Hauksbee stood out as an example of a female facilitator of science teaching for men, it took over 80 years for a school to be set up by a woman for the education of young women in mathematics and natural philosophy.

In the absence of documentary evidence, it is difficult to say why it took so long for this change to happen, but it is noteworthy that it took place within the wider context of publicised discussions of women’s place in society and their right to education. Well-known examples include Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Vindication of the Rights of Woman,[15] which argued for better education for women and was aimed at a male and female readership, published just three years prior to the opening of Margaret’s school in Blackheath. And lesser-known examples such as The Lady’s monthly museum, a periodical which aimed to provide its female readership with essays, letters, biographies and reviews in addition to stories and fashion news that was launched just three years later. While each example served a different purpose, taken together these three and the statement by Mary Knowles at the beginning of this paper are surely indicative of a growing feeling of discontent among some women during the late eighteenth century regarding the lack of education opportunities for women.

It was within this context that Margaret became an author. She wrote a pamphlet entitled A Compendius System of Astronomy in 1799 to accompany her lectures, which was endorsed by Charles Hutton and subscribed to by Dudley Adams (the instrument maker mentioned above). The content was typical of this kind of instruction pamphlet – descriptions and explanations of planetary motion and astronomical events. Her apologetic tone, which is clear from numerous comments in her preface such as, ‘At the tribunal of public and just criticism, I bow with humble confidence; acknowledging its discriminating judgement, admiring its general impartiality, yet, conscious of my demerits, dreading its award’,[16] indicates how unusual her authorship of this kind of material was, but also acts in anticipation of expected male criticism, which may or may not have materialised. In terms of reception of her book, it was reviewed extremely favourably in The Lady’s monthly museum by the ‘Society of Ladies’ in August 1801.[17] They described it as ‘a masterly compendium of astronomical knowledge’. In addition to reviewing recent publications, one of the self-stated aims of this periodical was to provide biographical information about distinguished ladies and it is clear that they wanted to say more about Margaret, but, like us, couldn’t find many details other than the existence of her schools and publications: ‘Of this lady we have at present been able to collect no other particulars…’[18]

Hutton encouraged Margaret to publish another work in 1806 entitled Lectures on Natural Philosophy. While less apologetic in tone, this book did include the reassurance that she was happy with her domestic responsibilities and that she was teaching as an extension of her parental role. This is significant given that some men in this period claimed that women who were interested in natural philosophy were neglecting their domestic responsibilities and were therefore bad wives and mothers. This was also an opinion that Mary rallied against in her Vindication.

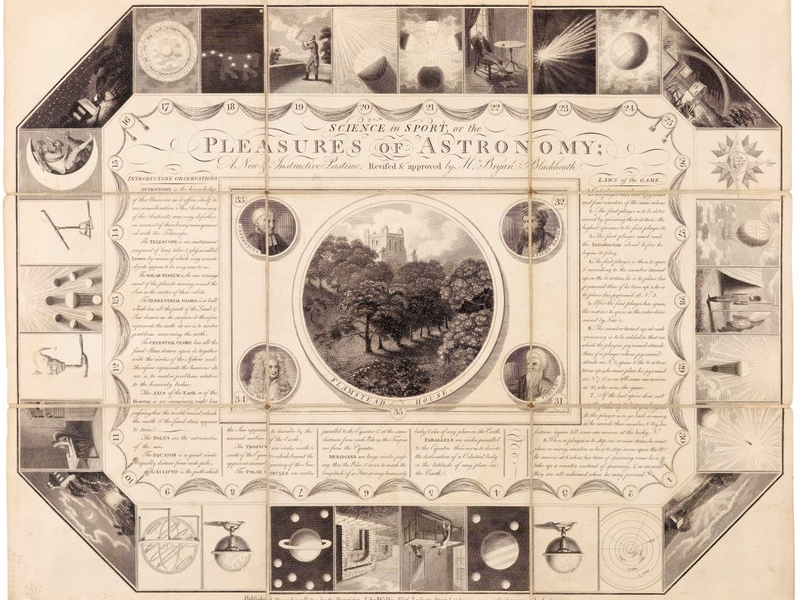

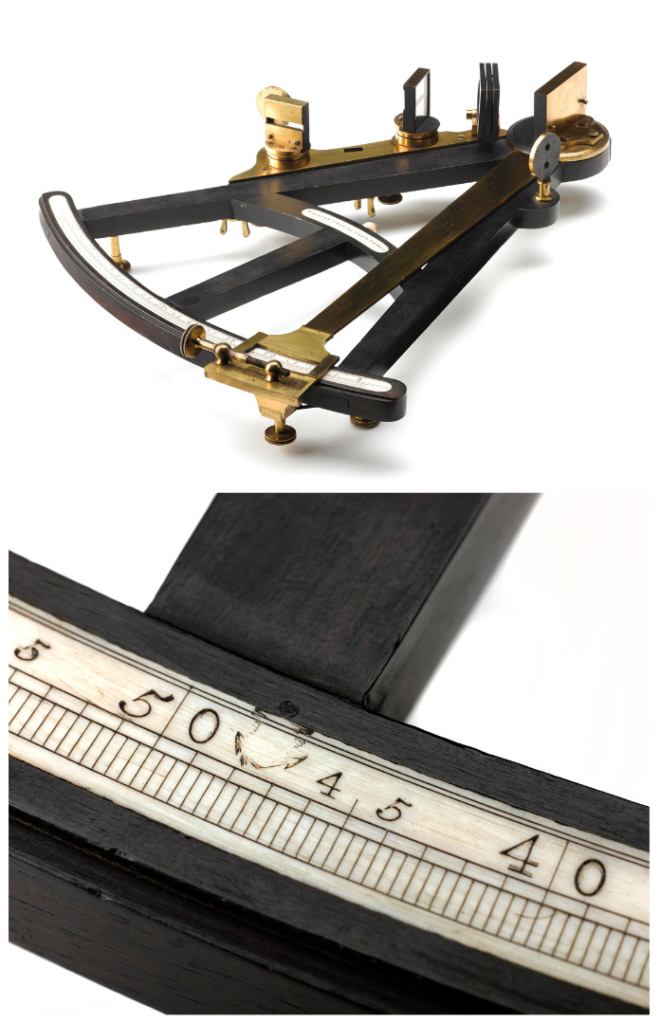

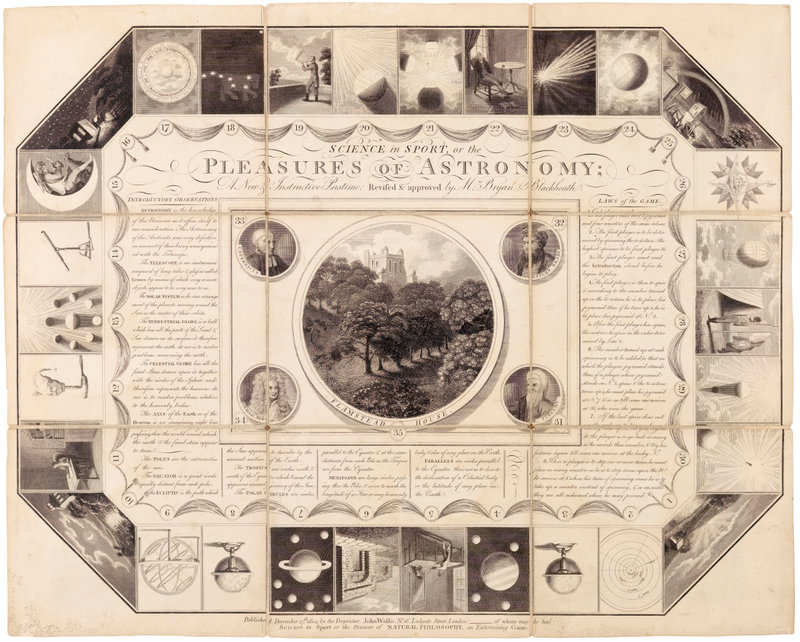

We know that Margaret’s reputation as an effective educator reached beyond the confines of her schools and her book readership by the presence of both her portrait (see Figure 9) and the survival of an astronomical board game that was endorsed by her (see Figure 10). The latter is entitled: ‘Science in Sport, or the Pleasures of Astronomy: A New & Instructive Pastime. Revised & approved by Mrs. Bryan; Blackheath, Published, December 17th 1804, by the Proprietor, John Wallis, No. 16, Ludgate Street, London: of whom may be had Science in Sport or the Pleasure of NATURAL PHILOSOPHY, an Entertaining Game.’ It is based on the contemporary Game of the Goose, which was adapted to a wide range of different themes to appeal to different audiences. Many of these were produced by John Wallis, a leading publisher of board games at the time. Wallis evidently felt that Margaret’s association with the game would act as a seal of approval in some quarters, possibly the parents of young women. The board consists of 35 numbered squares, which represent astronomical objects, instruments, principles and astronomers such as Ptolemy, Tycho Brahe, Nicholas Copernicus and Isaac Newton. Using a spinning top, players took turns to travel over the board, the object being to spin numbers up to 35 and reach the final square, representing Flamsteed House: ‘Whoever first arrives here is to take the title of Astronomer Royal.’[19] The game’s pedagogical method was mnemonics in the form of repetition and fact-association using moral lessons. Games such as this were usually accompanied by an instruction booklet, but an example for this particular game has not survived.

In this section we have shown that women contributed to the teaching of early science in London in the period. Our individuals in this section span the period 1713–1816, beginning as public science teaching was just taking off and continuing until the end of the period. While opportunities for women to do so were limited, by thinking about the nature of a contribution we can appreciate those made by people who might otherwise be glossed over as not having done much. The example of Mary Hauksbee has shown that women contributed to teaching by providing venues for it to take place. While little additional information is known about the logistics of this, it could be imagined that she did a little more than open her doors on the day in question. Her example also shows that women enabled the careers of others to flourish by assisting them in the way that she did with John Theophilus Desaguliers, who took over her late husband’s lecture series and presumably instruments and demonstration equipment. In terms of women’s education, the example of Margaret Bryan shows us that women were at last given some opportunity to attend lessons and the reference to her in the Lady’s monthly museum periodical indicates that its editors were aware of her work and keen to support it. We know from the contemporary publications of Mary Wollstonecraft that women were becoming increasingly frustrated by their lack of educational opportunities in this period. Despite the many challenges, women were active in their acquisition of new knowledge of natural philosophy.

Women as students and participants

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211502/004While unable to benefit from the same formal education opportunities as men, women found ways to actively study or participate in early science. Some were taught natural philosophy in their homes, either by their male relatives (fathers, brothers or husbands) or by a visiting tutor. Others may have learned indirectly, if they were permitted by what Fara (2005, p 76) calls an ‘indulgent father’ to sit-in on their brother’s lessons before the boy left home for university. Some attended public lectures on natural philosophy, as is evident from the numerous advertisements for lectures that claimed to be aimed at ‘ladies and gentlemen’. Others purchased books on the subject, some of which were intended for female readers. While it was perceived as socially acceptable in this period for a woman to attend an advertised lecture at a theatre or similar venue, it was not acceptable for them to visit coffee houses or attend meetings of the Royal Society. The only exception to the latter in this period was Margaret Cavendish, the first woman to attend a meeting of the Royal Society, whose work has been much discussed in the historical literature. Fara (2005) has highlighted the significance of women learning about or being exposed to early science in the home, but this can be expanded upon by broadening our definition of a student or participant in early science in this period and combined with the wider discussion in this paper. In that which follows we consider several examples of women in London who were taught natural philosophy in their homes, who participated in demonstrations elsewhere in London, or who were facilitated in their learning by people in London. We will also explore what newspaper advertisements and book subscription lists can reveal about female attendees of natural philosophy lectures and female book buyers. By doing so we broaden our definition of what makes a student or participant in early science.

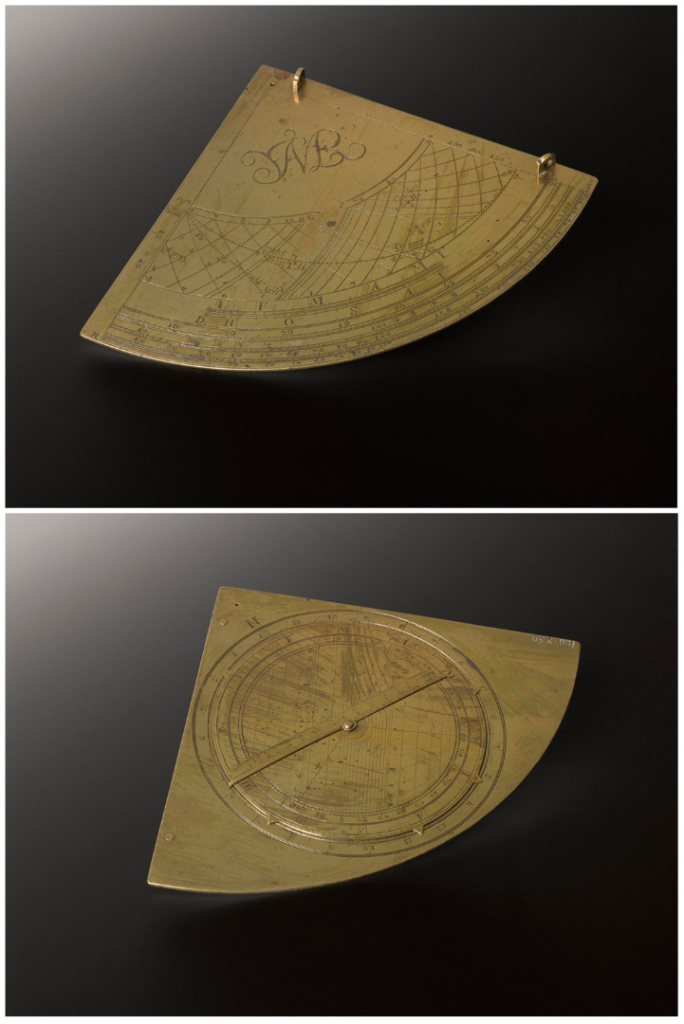

Without her husband’s diary, Elisabeth Pepys, wife of the famous Samuel, would have been largely unrecorded. Yet its pages reveal that he taught her mathematics and how to use a terrestrial and celestial globe for learning. She was approximately 23 at this time, just a few years older than her male contemporaries who were undergraduates at university. By the time the first entries in the diary were written, Elisabeth and Samuel had been married for approximately eight years and it is not known whether he had taught her throughout their marriage or had just begun. Elisabeth may have had some education at home before her marriage, but the extent of it is unknown. She was born into a middle-class family and at least a basic level of education could be expected. Regardless of any prior schooling, her interest in mathematics and globes is clear from Pepys’ diary.

By considering a number of entries from the diary, we gain a glimpse of the nature of the teaching that took place between husband and wife. On Sunday 6 December 1663, for example, we learn that they spent a whole afternoon on arithmetic. We only have Samuel’s word to go on, but he commented that Elisabeth had become competent in most aspects: ‘So my wife rose anon, and she and I all the afternoon at arithmetique, and she is come to do Addition, Subtraction, and Multiplicacion very well, and so I purpose not to trouble her yet with Division, but to begin with the Globes to her now.’[20] This comment also shows us how Samuel taught Elisabeth – it was in dedicated time blocks and for a very specific purpose. She was not taught mathematics in general, but the skills of addition, subtraction and multiplication. Given her progress, he had a plan for further learning, which was to give her a break from arithmetic before teaching her the skill of division, but to continue her learning by introducing the globes.

The diary contains a further five entries which mention Elisabeth’s learning using the globes. The dates of these references are from 14 January to 15 February 1663, which indicate that he spent a month teaching her about them. It is unknown whether he continued to teach her using the globes and did not record it in the diary, or if his teaching ceased. The phrases Samuel used to describe his teaching suggests something more formal than a brief chat. By using the terms ‘lesson’ and ‘lecture’, it can be imagined that he was explaining them and offering demonstrations to her: ‘Hence home, and after a lecture to my wife in her globes, to prayers and to bed.’[21] These lessons were normally conducted in the evening, for about an hour after dinner:

‘So home, reading all the way a good book, and so home to dinner, and after dinner a lesson on the globes to my wife, and so to my office till 10 or 11 o’clock at night, and so home to supper and to bed.’[22]

‘Upon this work till dinner, and after dinner to it again till night, and then home to supper, and after supper to read a lecture to my wife upon the globes, and so to prayers and to bed.’[23]

The experience of Elisabeth must have been shared by other London women in the period, but was not recorded in the same way because their husbands did not write diaries that have been remembered hundreds of years later, so the archival evidence is lacking. And even though these references to Elisabeth’s learning have been preserved, her experience has not been discussed within the context of early science in London. Yet her example shows us that both parties, husband and wife, demonstrated an interest and commitment to improving the latter’s knowledge of science. We can also see that instruments were often an important part of this learning and time was set aside for it.

During the reign of George III, whose wife Charlotte’s interest in science and learning was demonstrated by her own catalogue of scientific instruments and a personal library of over 4,500 volumes (Jay, 2017, p 305), Letitia Ann Sage took to the skies above London. Letitia was an actress who participated in a 90-minute hot-air balloon journey over London in June 1785 and published a pamphlet about her experience afterwards. While she has not been included in discussions of early science in London, other than passing references to her possibly being the first woman to fly in a balloon, we consider her here as a genuine participant given the content of her publication in addition to her flight. Letitia reported that 100,000 people came to watch the ascent at St George’s Fields.[24] This was probably an accurate estimate as it is well known that balloon ascents drew huge crowds (Brant, 2017, p 3).The voyage brought instant fame to Letitia, who may have been well-known to theatre-goers in Covent Garden, but became famous (or notorious) as a ‘female aeronaut’ in the summer of 1785. Her portrait was painted (see Figure 11), she was clearly able to buy expensive clothes, and appears to have received enough money or support that she did not need to return to acting for nineteen years (she is recorded working in both London and Dublin by 1804).

Some people were highly critical of her in the press at the time – claiming that she kept fainting and that she broke some of the instruments. The underlying message of these criticisms was that women were weak and ill-suited to endeavours associated with natural philosophy, such as experimental ballooning and caring for instruments. It is not surprising that male observers were equally critical of Letitia in this context. It was unusual for women to participate in scientific endeavours and was not welcomed by many, who reacted by passing negative comments or trying to discredit the woman concerned as had also been the response to Margaret Cavendish’s visit to the Royal Society in 1667. It is noteworthy that men were not described in this way, even if they did exactly the same things.

In fact, in Letitia’s published account of the events, entitled A Letter Addressed to a Female Friend and published in 1785, we get a very different account.[25] When it was realised that not everyone could go up, Letitia said she was worried about being disappointed, but remained firm. She said that some reports described her as nearly fainting, but she said this was untrue and that she was never more in charge of her reason. Addressing the underlying assumption that she was weak and ill-suited to balloon flying, she explained that, on the contrary, she was a brave character who enjoyed this kind of activity more than anything else and was interested in natural philosophy. On the title page, she described herself as the ‘first English female aerial traveller’ and began the letter by saying that she had accomplished her favourite experiment.[26] She cited the failed attempt previously and said that she was angry to hear that people were saying it didn’t happen because she was frightened, which she strongly refuted. She countered claims that she fainted during the flight, indicating how irritating she found the comments, by explaining that she bent down momentarily to lace the door shut to assist the piloting of the balloon mid-flight.

Letitia described the balloon and the experience in a methodical manner, in the vein of descriptions of experiments published elsewhere such as in the Philosophical Transactions, saying, for example, that the balloon was a fourth filled when she arrived on site. She used temporal references throughout her account, suggesting that she was using a pocket watch to make a note of timings – for example, she said that the team began filling the balloon at 9 o’clock; that they took her to the balloon at ten minutes past one to do some testing; and that they ascended at 25 minutes past one. She also divided her account of the journey according to time – using temporal references as headings – for example, twelve minutes before two. In some of the sections, she added the details of compass bearings and thermometer readings, for example: ‘6 Minutes before 2, Ther. 59, hyg.3, direction West.’[27] She described the movement of the balloon scientifically – observing that George threw out some ballast by degrees when the balloon began to descend too quickly and that this restored its equilibrium.

In terms of instruments, she referred to George’s ‘observation equipment’ being put on board at the start. Her references to temporal units, temperature and compass bearings demonstrate her interest in the nuts and bolts of the experience, rather than just going along for a pleasant ride. She commented that she brought a notebook along because she was very interested in the experience and wanted to record it. She noted that she was pleased that George did not think it ‘…a degradation to communicate his observations to a woman’.[28] This indicates that while George may have been taking readings from his instruments, it was Letitia’s desire to make a record of them so that she had what she perceived to be an accurate record of her experience, which in itself was typical of others interested in science at this time. This in itself indicates an awareness of what constituted a detailed, scientific record.

Like other female authors in the period, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Letitia is keen to point out that there was something severely lacking in female educational opportunities when she said:

It is from his conversation that I am enabled to entertain you with some remarks, which would have been, perhaps, beyond the compass of my own observations. Female education does not usually leave the mind capable of drawing accurate conclusions from events, which may arise in the peculiar situation I am describing; where particular effects are produced from a variety of concurrent circumstances, every one of which would appear plausible to the reasoning of the moment.[29]

This seeming awareness of women’s lack of analytical ability in comparison with men, due to education rather than innate ability, is perhaps indicative of why there is not more archival material relating to women’s participation in science at this time. If many were not taught how to experiment or think in a ‘scientific’ manner, then it is hardly surprising that they thought it was not for them. Luckily, those who were determined enough, like Letitia and the other women referred to throughout this paper, managed to get involved, but we can only imagine how many more could have made significant contributions to early science had they been enabled to do so.

Letitia went on to say that she broke one of the instruments: ‘When I knelt down to lace the gallery, I unfortunately put my knees upon the barometer, and broke it, so that we were entirely without a barometer; and of course Mr. Biggin could form no perfect opinion respecting our altitude.’[30] While many at the time probably used this as an excuse to claim that women were not suited to handling or using instruments, it would be very unlikely that men never broke instruments (or the repair business would have been non-existent), but their mistakes have not been recorded or described in this manner. Furthermore, one could point out that George had not stored or secured his instruments properly and his sloppiness in this regard was the reason for the damage.

Letitia observed the experiments which George performed, including trying to use his compass in the clouds (which did not work) and an electrical experiment (by which he concluded that the electricity of the cloud was negative). This is further evidence of Letitia’s interest, it could be imagined that a non-interested individual (male or female) would not have made such a record.

When the journey ended and the balloon descended near Harrow, Letitia expressed her disappointment that George intended to leave her there and carry on alone:

…and after leaving me in the care of some of the hospitable people of the neighbourhood, he meant to ascend again, and continue his voyage as long as the Balloon would carry him. It was then that a little trait of female weakness, I confess to you, crept into my heart. I wished him not to proceed further than I could accompany him. I envied him a lengthened journey ; but. as sentiments which are not natural make but slight impressions, I soon re-covered my own and as it appeared to be so much wished by Mr. Biggin to proceed, I bade him adieu with infinite pleasure ; and only looked forward to his safe return.[31]

This example further demonstrates her interest in natural philosophy and ballooning, but also the opinion of women who were interested in such pursuits. It was not ‘feminine weakness’ that made her want to carry on and disappointed that she could not, but an interest in ballooning. Had she been a man, the experience would not have been described in this way.

While Elisabeth Pepys and Letitia Ann Sage left behind a record of their interests in natural philosophy, others surely existed who have left little or no trace at all. Two final places for discovering references to more women who were students or participants in early science lie with newspaper advertisements and lists of subscribers to publications.

Public lectures in natural philosophy were very popular in London (and beyond) during the eighteenth century and there were many advertisements in newspapers for lectures in theatres, taverns, coffee houses and private homes. Some of these advertisements included women as part of their target audience. Records of women attending lectures, with the exception of Queen Caroline who is known to have attended at least one, are extremely difficult to find, so we must make do with what we can ascertain from the advertisements themselves. If nothing else they tell us that women were welcome at the lectures and, while we cannot be sure exactly who attended, it is very likely that some women did, given how interested many were and indeed how many subscribed to associated publications (discussed in more detail below).

Advertisements and the title pages of pamphlets written to accompany courses indicate that lectures on experimental philosophy were aimed at women in addition to men and it seems likely that women attended the courses in addition to reading the associated books. In 1765, for example, Benjamin Martin published a pamphlet whose long title described his course of lectures as being: ‘…for the use of such Gentlemen and Ladies as would acquire a competent knowledge of this science without mathematical learning…’[32] Similarly, pamphlets which aimed to teach some of the principles to people who could not attend the lectures featured titles that were inclusive for ladies, for example, James Ferguson’s Young Gentlemen’s and Ladies Astronomy and Martin’s The Young Gentleman’s and Ladies Philosophy containing a general description and use of philosophical instruments.

Given the popularity of natural philosophy in this period, it is not surprising that crowds could be drawn to observe science-related events, such as balloon ascents (as mentioned above) and natural phenomena such as eclipses, for example the solar eclipse of 1724, which led to people erecting 50-foot-high viewing platforms and the sale of darkened glasses to enable safe observation (Stewart, 1992, p 146–147). When the 1761 transit of Venus took place, Benjamin Martin placed a number of advertisements in London newspapers which invited ladies, in addition to gentlemen, to collectively observe the event with him. It stated: ‘Mr. Martin, BEGS Leave to acquaint Ladies and Gentlemen, who are curious to observe the TRANSIT of VENUS, TOMORROW Morning, that he has provided a commodious and well situated Room for that Purpose…’.[33] It is significant that Benjamin made it clear that he was providing a suitable room for this event. As noted above, some group discussions of natural philosophy took place in coffee houses in this period and these were not deemed suitable venues for women. Benjamin’s advert goes on to say that those attending will be supplied with ‘…a Variety of large Reflecting and Refracting Telescopes, furnished with different Sorts of Micrometers and other instruments…’.[34] Attendees of natural philosophy lectures and demonstrations in this period expected to see or have access to the latest instruments, and lecturers ensured they mentioned these in their advertisements to draw an audience. In this particular example the eighteenth-century transits were of great national interest and it is significant that ladies were included in the enthusiasm surrounding it.

Given that archival evidence of women attending public lectures is scarce, surviving lists of subscribers to publications on natural philosophy and specifically those associated with lecture courses become more significant as evidence. One rare example can be found in Millburn’s (1988) analysis of the library of George Adams the Younger, whose wife Hannah was discussed above. This evaluation sheds light on the number of female subscribers to one of Adams’ publications. The Lectures on Natural and Experimental Philosophy of 1794 was published in five volumes and priced at 24 shillings (Millburn, 1988). Out of the 940 total number of subscribers, 36 were women, which accounted for approximately 3.8 per cent. While this number seems rather small to a modern reader, given the context discussed in this paper it is valuable evidence that women were not only interested in natural philosophy, but were purchasers of publications on it. Moreover, it is significant that these were lectures as it shows an additional degree of participatory learning.

Of the 36, five were aristocratic ladies, and 31 were middle-class women. There were also four royals cited as subscribers, but their identities were not specified, so it is unknown whether this number included any of the female members of the Royal Family. The aristocratic women included: Lady Blois of Cockshut Hall; the Dowager Lady Cavan of Upper Seymour Street; Lady Cavan of Sackville Street; Lady Dormer of Housham, Oxford; and Lady Lindsay of Burley Hall in Berkshire.

Most of the women on the list gave London addresses from Dulwich to Harley Street and from Fetter Lane to Berkley Street. Yet a small number gave addresses in Manchester and this was also reflected in the addresses of male subscribers. Natural philosophy lecturers did travel around the country in this period and major provincial towns were home to significant audiences.

It is significant that of the 36 female subscribers, only three were subscribers from the same household as a male subscriber (Miss Bentinck of Stratton Street; Miss Marsham of Berkley Street; Miss North of Bridge Street), suggesting that they were genuinely interested in natural philosophy in their own right and had a degree of autonomy over the purchase of their own books. Furthermore, of the 31 middle-class women, 17 were married and the remaining 14 were single ladies and possibly adolescents. Given that only three of these were from the same household as a male subscriber, the approximate 50/50 split suggests that women of this social standing had enough autonomy to enable them to pursue their own intellectual interests and it is significant that natural philosophy drew the attention of many of their number. It was noted above that indulgent fathers sometimes allowed their daughters to sit in on their brother’s lessons, but this subscription list appears to show that some young ladies were able to take a more active role.

In this section, we have shown that despite the challenges faced by women from a society which limited opportunities for education based on gender, some women were able to act as students of, and indeed participants in, early science in the period. The individuals that we have considered in this section neatly represent the period 1663–1794 and have revealed some significant information. In terms of the relationship of the women considered to their male counterparts, two issues have become apparent. Firstly, that on the one hand, many women were actually encouraged and facilitated in their scientific pursuits by their male relatives or friends, such as Elisabeth Pepys being taught mathematics and use of the globes by her husband and, to some extent, Letitia Ann Sage who was enabled to take part in a balloon ascent and assist in making scientific observations during the flight by the owner of the balloon, George Biggin. On the other hand, our discussion has shown that women did have to play an active role if they wanted to pursue their interests and did, of course, come up against some opposition. Advertisements of public lectures show us that women were one of the target audiences of many lecturers in the period, but they could not attend other discussions of natural philosophy that were taking place at the Royal Society or in the city’s coffee houses, whereas some men went to all of these places so were more included. The presence of women in subscription lists to George Adams’ pamphlet on his natural philosophy lectures show that, despite the challenges, women were keen to get involved. The examples of women from different sections of society, middle-class women, aristocratic ladies and even royalty, indicate how far-reaching the interest was and, indeed, how many different women were interested in science.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211502/005Through the consideration of ten named individuals and groups of others, this paper has demonstrated that women played significant roles in the development of London as a ‘science city’ in the period 1650–1800. By expanding our definition of what constituted a contribution and bringing together examples of different types, we have shown that women did not play a single role; they contributed to the emergence of a scientific culture in London in many different ways. As we have seen, they were makers and retailers of instruments, educators, and active participants in science activity including authorship. The examples we have considered neatly represent the period 1650–1800, with the exception of the women who can be considered to have taught science. In this category of contribution, our coverage ends near 1800, but does not start until 1713. This discrepancy closely matches the context of public science lecturing, which did not begin in earnest until the first few decades of the eighteenth century. While shining a spotlight on the roles played by women, this paper has shown that women did not work in isolation and should therefore not be seen as a distinct category, but as part of the rich fabric of the city – making essential contributions, but fitting into a larger whole. Due to a lack of evidence and other research priorities, women’s contributions to science in this specific period have not been fully considered before. We hope to have in-part redressed this imbalance and call for more inclusive approaches in the future so that the roles played by women can be acknowledged, even when evidence is sparse.

All of the women discussed in this paper were individuals with their own reasons for involvement in science, but several factors united them all and influenced their experiences. These were: the contemporary perceptions of women; networks in London; and the wider and growing demand for scientific knowledge. In terms of perceptions of women with respect to science, it is well known that natural philosophy and the making and using of scientific instruments was considered to be a male domain. While it is also known that in spite of this, women made significant contributions to science, the variety of which have been demonstrated here, it has also been shown that these prevailing perceptions did to some extent define all of those contributions and certainly influenced the manner in which they were each made and, indeed, the extent to which they were recorded (or not). While instrument makers such as Sarah Ramsden were encouraged and facilitated by male relatives and friends, all of the women discussed in this paper were restricted in the degree of their involvement in science by many men throughout the period 1650–1800. The instrument maker Mary Edwards, for example, was not permitted to take John Yarwell on as an apprentice formally and was not permitted to become a Freeman of the Spectaclemakers’ Company. Similarly, writers such as Letitia Ann Sage faced strong criticism when they attempted to participate in science.

In terms of science networks in London at this time, there were of course several of varying size, each of which interconnected with others at various points, but none were completely isolated. To name just a few, there were natural philosophy networks such as the Royal Society and Gresham College that were official organisations, and coffee houses which attracted specific groups of people (such as fellows of the Royal Society, lawyers or physicians), there were craft networks such as the City of London Livery Companies, family groups connected by marriage and ancestry, and Master and Apprentice groups (where good relations had continued). Connection points were at several places and changed over time, as did the composition of the different networks. Connection points occurred when Fellows of the Royal Society visited instrument makers to have new instruments constructed, or when instrument makers sought new contracts from government bodies. Intertwined with all of this were the instrument-buying, lecture-going citizens who were made up of wealthy merchants, clergymen, lawyers, mathematical practitioners, successful craftsmen, aristocrats and others. All of the women discussed in this paper made use of these different networks to pursue their interests in science, whether that was the instrument maker Mary Senex, who advertised her globes in trade cards and catalogues and wrote to the Royal Society, or the educator Margaret Bryan, who ran schools for young women and girls and used instruments to teach them.

The wider and growing demand for scientific knowledge included a growing commitment to the need for new knowledge about the natural world, both for the benefit of the mind (individual and collective) and the state, and an increasing demand for scientific instruments and apparatus, which was related to the former. Women who were committed to learning about science made the most of opportunities that were slowly opening up to them whether that was participating in a balloon ascent or subscribing to publications on natural philosophy.

For the three types of contribution considered in this paper, which are not fully comprehensive, more has been said about some than others, but this is not due to poor scholarship. In one sense the lesser populated examples are the most significant because they identify invisibility, or partial visibility, in the archival record and historiography. We hope that this paper encourages others to continue to ask questions about the role of women in this period and to keep challenging the definition of a contribution so that more inclusive historical narratives can be brought to the fore.