Collecting twenty-first century science: an analysis of public and professional perceptions

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231902

Abstract

This article covers the key findings from a set of qualitative and quantitative research investigating the relationship between public and professional perceptions of contemporary collecting. Areas of congruence and disconnect were studied using a survey, distributed to public and professional respondents, and a series of interviews with curatorial and directorial staff at two case study science museums: the Science Museum in London and the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden. This research demonstrated that while there were certain areas of disconnect and hesitancy, both groups supported the acquisition of twenty-first century material in science, technology and medical museums, acknowledging the importance of such collecting strategies. The data also highlights the importance of contemporary material for audience engagement and development of science capital, enabling visitors to deepen their understanding of the past, present and future through discussions of current science, technology and medicine and its role within society.

Keywords

acquisition, audience engagement, collecting strategies, contemporary collecting, perception analysis, post-museum, professional perspective, public perception, qualitative data, quantitative data, Rijksmuseum Boerhaave, Science Museum

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/The recent Covid-19 pandemic has bought contemporary collecting to the forefront of many curators’ minds, as they seek to acquire objects that represent its dramatic impact on daily life. The search to acquire objects such as rainbow drawings and other representations of people’s daily lives and of broader societal reactions to the pandemic has been carried out by many institutions, including the Museum of London and the Victoria & Albert Museum (Atkinson, 2020; Volsing, 2020). Such acquisition practices have attracted public attention and engagement with these heritage institutions. However, while public awareness of contemporary acquisition techniques is growing, there has been limited research into the public interest in modern items within museums and how the incorporation of twenty-first century material impacts the relationship between the museum and its visitors. This highlights a gap in our understanding of these processes, a void which this research aimed to address by developing a deeper appreciation of both public and professional perceptions of contemporary collecting in science, technology and medical (STM) museums.[1] Through both interviews and a survey, carried out in 2019, data was acquired which allowed a more in-depth analysis of opinions on this topic. This paper will outline a summary of these results, while also providing an insight into three key emerging issues: the acquisition of context surrounding contemporary scientific developments, the concept of neutrality in museums, and the ability of twenty-first century material to enhance visitors’ understanding of contemporary science. By developing a deeper understanding of attitudes towards contemporary collecting, from both museum professionals and the general public, this research builds a picture of the importance of this practice, concluding that there is a need for increased uptake of contemporary collecting in museums.

A brief history of contemporary collecting

The practice of contemporary collecting is not a new phenomenon within museums and, especially in STM institutions, it can be traced back to the nineteenth century. During this time many science museums aimed to display ‘the latest and best in the useful arts’ (Alberti, 2017, p 2), with collections formed from a combination of contemporary and historic artefacts (Bud, 2017, p 51). This practice continued into the twentieth century, with STM museums becoming spaces for visitors to learn about modern technology through displays which juxtaposed contemporary material alongside historic examples, illustrating the evolution of practice (Alberti, 2017, p 2). This integration of the past and the present was popular among visitors during this period and emphasises the presence of a clear alignment between the public and institutional perception of the value of contemporary collecting.

A fascination with the representation of contemporary science continued into the 1960s, when public interest in topics such as space exploration encouraged STM institutions such as the Science Museum to increase their representation of modern material (Anthony, 2010, p 98). However, the period of deindustrialisation in the UK in the 1970s caused a drop in interest among the general public for displays of current science and technology (Bud, 2017, p 58). As fewer people were employed in manufacturing, companies and production processes became more removed from society and many people lost their personal connections to modern material and machinery (Bud, 2017, p 58). Public interest in industrial technology and related scientific developments decreased, stimulating a ‘resurgence of the science of the old’ within museums (Anthony, 2010, p 106). By the time of a 1988 public survey led by John Durant,[2] interest in science was noted to be high but self-reported knowledge, and ability to correctly answer questions on these topics, was low (Durant et al, 1989). This was a key finding for the public understanding of science movement, demonstrating that ‘although the public is largely uninformed, it is also largely interested in science’ (Durant et al, 1989, p 14). This limited knowledge may have contributed to the disconnect between the general population and contemporary science, a divide which continued to grow into the 2000s, as public scepticism of STM developments persisted. An investigation by the House of Lords in 2000, for example, reported that ‘many people are deeply uneasy about the huge opportunities presented by areas of science including biotechnology and information technology, which seem to be advancing far ahead of their awareness and assent’ (Select Committee on Science and Technology, 2000). It is possible that during these times of increasing disconnect between science and the public, various STM museums lost focus on this element of their past acquisition strategy. Even though some museums continued contemporary collecting following this period of deindustrialisation (exemplified by the Science Museum in London, which expanded its contemporary collecting efforts in the 1980s), one can argue that deindustrialisation triggered a move away from a modern acquisition strategy in other institutions (Bud, 2017, p 269). However, this trend is difficult to accurately discern due to the dearth of literature regarding contemporary collecting and related acquisition strategies, although discussions surrounding this topic are increasing year on year. Public opinion of contemporary collecting has also been relatively undiscussed. Although the House of Lords report made clear a growing disconnect, the trajectory of this trend in the last twenty years cannot be clearly understood. Nevertheless, many museums, such as National Museums Scotland, are now actively increasing their focus on contemporary acquisitions, and discussing these shifts within museological literature, which may correlate to a resurgence of public interest in these topics (Alberti et al, 2018, p 402). Thus, while a study of the history of contemporary collecting in science, technology and medical museums demonstrates that there is historic precedent for cohesion between public and institutional views of the value of this process, this research aims to form a current and more cohesive overview of these opinions and establish whether these perspectives are still congruous in the twenty-first century. Furthermore, this research will investigate whether contemporary objects can enhance public understanding of science by illustrating current developments and providing the vehicle through which individuals can engage with these complex and sometimes ethically challenging topics.

Methodology

Firstly, it is important to establish the definition of ‘contemporary’ used within this research as there is no current set definition for the term within museological literature. Concepts range from post Second World War, to encompassing the past five years on a rolling basis (Rhys, 2011, pp 13–14). While these definitions suit varying situations and institutions, this research defines contemporary as anything from within the twenty-first century, encompassing roughly twenty years of material at point of interview/survey. This definition was used to provide a clear delineation for public and professional respondents when considering contemporary material while also ensuring that material could feasibly be termed ‘current’. However, it is important to acknowledge that each institution will define this term differently. Future research may benefit from a more specific definition of ‘contemporary’, but for purposes of hypothesis and insight generation in this research, the boundary of the twenty-first century was deemed sufficient.

This research consisted of two data collection strategies, interviews and a survey, both carried out in 2019. The methodological structure for the survey and interviews followed a social anthropological approach and conformed to the ethical viability guidelines outlined by the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and the Commonwealth (ASA, 2011). The use of methodological pluralism within this research reduces the limitations of each methodology and enables the identification of underlying themes, as well as providing a more in-depth insight into practices at the two case-study museums where the interview participants were based.

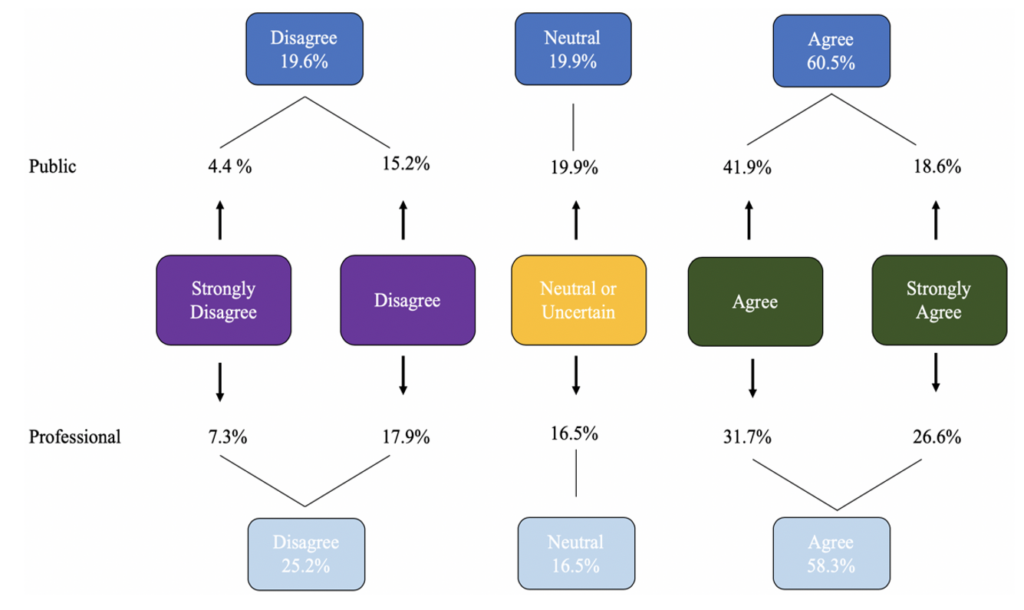

The survey acted as the main methodology for acquiring public opinions on contemporary collecting and enabled responses on the topic from a broader range of professionals, when compared to the interviews. This self-administered survey was distributed online, using personal social media accounts (Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn), as well as more sector-specific channels such as the UK Contemporary Collecting Group email list and some individual professional contacts. Distribution across social media also created opportunities for the link to be easily shared by others, broadening the scope of the survey. While this methodology created a sufficiently random and diverse sample for this case study, it illustrates an area of improvement for future research. The survey itself was open to all, with no restriction on factors such as age, but interestingly received no responses from anyone within the ‘16 and under’ category, an area of potential expansion in future research. The structure of the survey was carefully formatted to maximise the response rate and accuracy of the results and contained a variety of open and closed questions (Bernard, 2006, p 253). In total it received 136 usable responses in just over two weeks (17 days). The survey was mainly formed of five-point Likert scale questions. The wording of these, and all other questions, was carefully considered to avoid unintentional bias, as it has been shown that question structure can impact responses (Robinson and Leonard, 2018, p 5). With the aim to test any such impact on the survey, it was decided that if any of the Likert scale questions had a ‘neutral/unsure’ response rate of fifty per cent or more this could indicate issues with the structure of the question and require further investigation as to whether it should remain within this study. However, none of the Likert scale questions reached this threshold so all were considered valid for further research. It is also important to note that these neutral/unsure responses were not removed from any analysis as they provide an important insight and such exclusion can reduce the validity of the sample and increase chances of bias (Denman et al, 2018, p 2). The five Likert scale responses were further reduced into three categories, to increase clarity during statistical analysis (Figure 1).

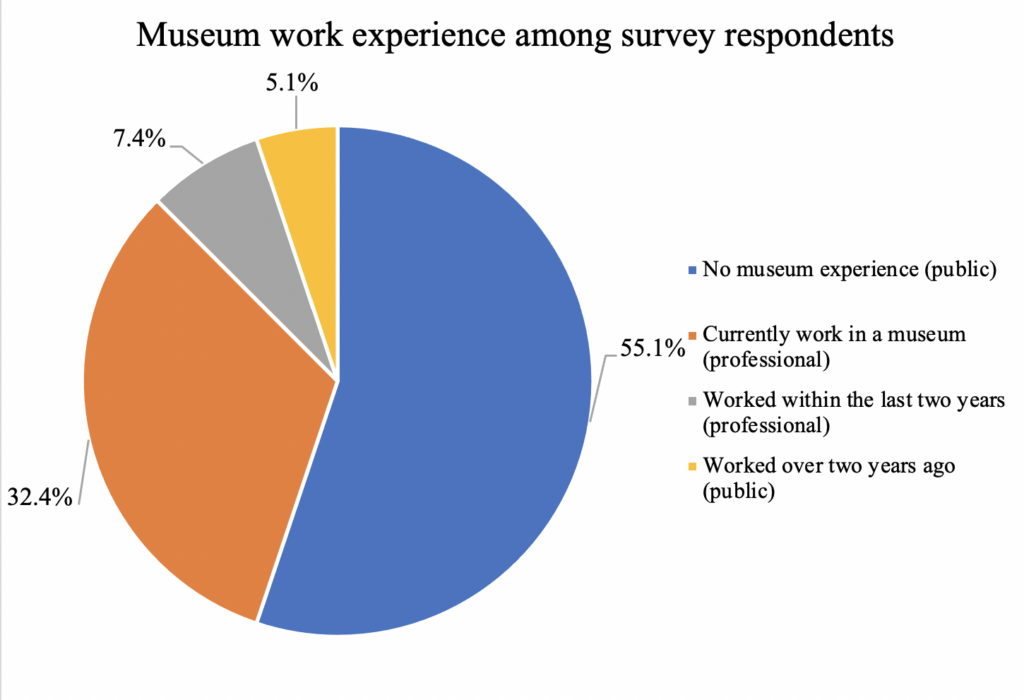

Public and professional respondents were sent the same survey which branched after establishing core demographic data. Within this research the public was categorised as anyone who had never worked within the museum/heritage sector or anyone who had been away from the sector for over two years. This categorisation was decided upon because current insight is especially necessary when dealing with contemporary collecting which, unlike other aspects of the museum sector that can be slow to change, has undergone significant transformation in the last few years (Phillips, 2004, p 369). In total, sixty per cent (n=82) of the responses were from the public and forty per cent (n=54) were from individuals working within the museum or heritage sector, providing an insight into both perspectives.

In contrast to the survey, the interviews were solely focused on professional participants. The interviews themselves followed a semi-structured style, enabling a certain level of consistency and ensuring all key avenues of questioning were covered, while also maintaining a flexibility that allowed interesting aspects of discussion to be expanded upon (Bernard, 2006, p 212). Each interview consisted of nine question prompts, five of which were highlighted as key areas of discussion and effort was made to ensure that these core questions were covered in every interview. The interview topics were derived from literature research and aimed to cover the same general themes as the survey, enabling deeper insight into these issues. Extra prompts were also included to provide further areas of discussion if required, ensuring use of the full 45–60 minutes allotted for each interview. The prompts were written carefully to remove any leading questions and avoid influencing participant responses. The interviews were recorded, transcribed, coded and analysed following a standard method of qualitative analysis, as discussed below. All of the data was anonymised in accordance with the ASA guidelines (ASA, 2011, pp 2–3) with only participants’ job titles and museum recorded alongside their transcript to allow identification of institutional differences.

In order to fully understand the findings of this research, both qualitative and quantitative analysis was undertaken. MAXQDA[3] was used to code and analyse the qualitative data (interview transcripts and open-ended survey questions) and SPSS (Statistics Package for the Social Sciences) enabled descriptive and non-parametric statistical analysis of the quantitative data (closed-ended survey questions) (Kuckartz and Rädiker, 2019). While MAXQDA enabled visualisation of the coded data, the codes themselves were created using ‘a flexible deductive process of coding’ (Fletcher, 2017, p 182) which ensured that personal expectations of the data did not distort final observations (Saldaña, 2013, p 146). A set of pre-defined areas of interest were developed prior to analysis, based on themes within the literature (Lewins and Silver, 2007, p 86), but these codes were fluid, enabling inductive development of the coding system, involving renaming, removing, altering and creating codes during analysis to enhance their clarity (Lewins and Silver, 2007, p 84). For the quantitative analysis, non-parametric tests were chosen specifically as they do not rely on any assumptions about the normality of the data (Martin and Bateson, 2007, pp 107–108).

Caveats and future opportunities for research

As a case study, aiming to generate new hypotheses, this sample was necessarily small. In order to fully explore the insights identified in this paper, further research, interviews and surveys should be performed, aiming to increase survey participation amongst both respondent groups. This would ensure a greater diversity of participants, potentially enabling analysis of the influence of other factors such as education, which could not be tested during this research. Additionally, the research scope should be broadened to include a greater proportion of public respondents who are not regular museum attendees. While both the survey and interviews had international scope, with survey respondents from the UK accounting for 64 per cent, and the other 36 per cent split evenly between the Netherlands (18 per cent) and ‘other’ countries (18 per cent), the data did not illustrate significant national variation within these opinions. In future research it would be interesting to expand this study of national variation and include both survey and interview responses from a broader, more global, selection of countries. To support greater international reach, the survey could also be made available in a variety of languages, facilitating input from non-English speakers. Additionally, while the methodological approach described was sufficient for this case study, future research would benefit from a greater variety of survey distribution methods to ensure a more random and diverse respondent group. An increase in the number of professional interviews undertaken, as well as the addition of public interviews, would also enhance any further study, enabling a more varied and nuanced understanding of public and professional perspectives.

Respondent and findings overview

Interview overview

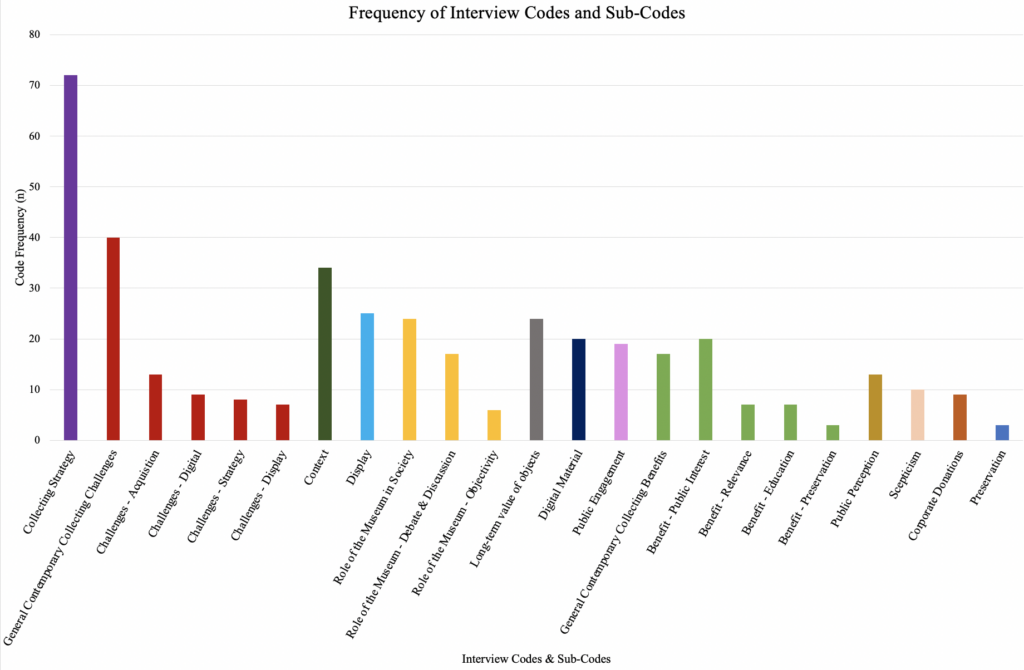

The interviews carried out for this research provided an insight into specific opinions of individuals working at science, technology and medical museums. Five interviews were carried out, two with staff from the Science Museum in London, and three with staff at the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave in Leiden. The transcripts of these interviews were coded and analysed to pick out the key themes covered in the discussions. Several themes were of note on initial analysis. When solely looking at the frequency of words appearing in the transcripts ‘people’ (n=155) and ‘objects’ (n=167) were focal points of the interviews, implying that public interest and engagement with audiences and broader social context is as important an element within contemporary collecting as the objects themselves. Another prevalent area of discussion within the interviews was ‘general contemporary collecting challenges’ (ten per cent, n=40) a catch-all term which included aspects such as legal challenges and staff hesitancy towards contemporary collecting, topics that were not covered by any of the other deductively developed interview codes. However, while Figure 2 reflects the frequent discussion of challenges compared to benefits, the prevalence of these codes is also likely to be linked to the specific questions asked, many of which directly queried a variety of challenging aspects of contemporary collecting, such as the acquisition of digital material. Interview coding analysis provided an insight into the opinions of five members of staff at two STM museums and illustrated a generally positive view towards the practice of contemporary collecting, likely influenced by the involvement of interviewees with this practice at their institutions. However, this data does not fully illustrate the opinions behind such discourse, illustrating the need for the survey, which reached a broader range of individuals and therefore provided a more conclusive insight into the presence of congruence or disconnect between public and professional views of contemporary collecting.

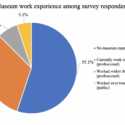

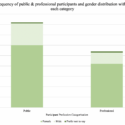

Survey overview

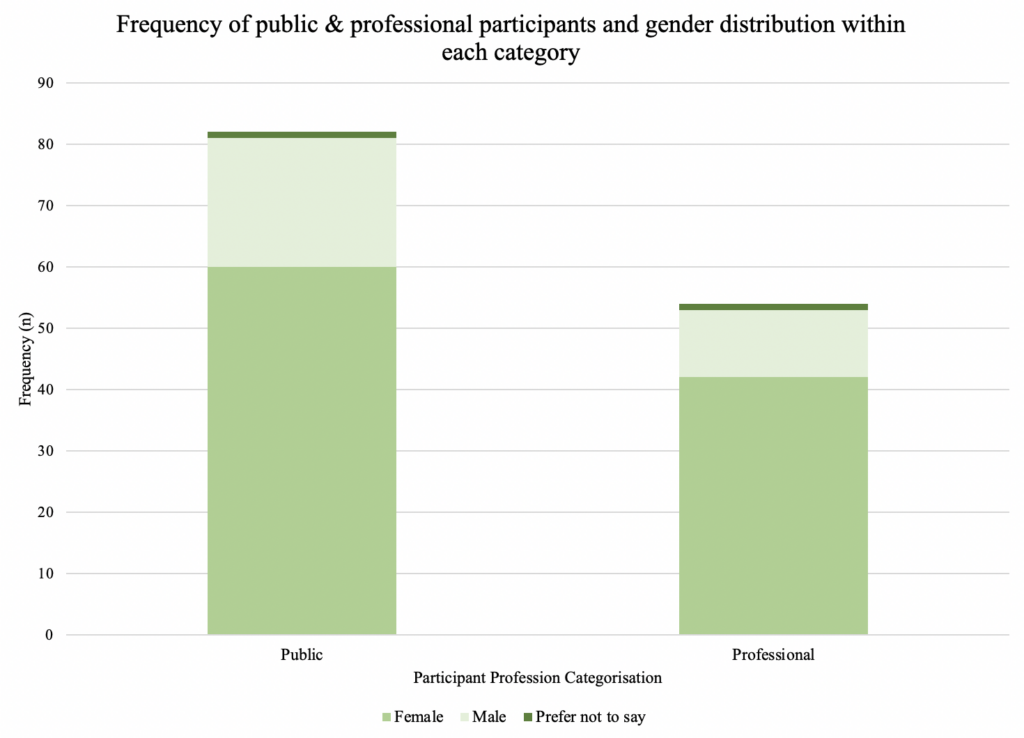

As mentioned above, the survey respondents consisted of sixty per cent public and forty per cent professionals (Figure 3). The data set is also heavily weighted towards female respondents with 73 per cent of the public and 78 per cent of professionals identifying as female (Figure 4). Furthermore, participation was significantly greater among younger age groups, with fifty per cent of respondents falling within the 17–29 category. Data also revealed that the public survey respondents had a strong base-level of engagement with museums, with 67 per cent reporting visiting museums three or more times a year, illustrating a highly culturally-engaged respondent pool. Although this level of cultural engagement is not necessarily reflective of the public as a whole, as only 51 per cent of English respondents to a government survey recorded attending a museum or gallery in 2019/2020, the term ‘public’ will still be used within this research for ease of identification (DCMS, 2020). Additionally, museum visitors themselves are a varied group consisting of a variety of individuals and future research would benefit from further visitor demographic analysis and study of variation in their responses to contemporary collecting. Therefore, as mentioned earlier, to perform a more robust analysis of public and professional perceptions, the ‘public’ category should be further developed with particular focus on including those who are not frequent museum visitors and further definition of those who are regular museum attendees.

To gather additional demographic information about professional respondents, individuals were asked what type of institution they worked for. They came from a wide range of organisations, with a large proportion (45.5 per cent) from STM (25.5 per cent) and social history museums (20 per cent). Furthermore, 82 per cent of respondents noted that their institution acquires twenty-first century material. Although, interestingly, 70 per cent of those who provided further information about their collecting strategy stated that they had no specific contemporary collecting protocols, or if they did, they were unaware of their existence.

This demographic information has provided both an insight into the general respondent group as well as illustrating more specific details regarding public museum-engagement and the institutions to which the professionals belonged. As mentioned in the caveats section above, this demographic would benefit from broadening in future research, but provides a sufficiently varied participant pool for this case study.

Perceptions of the benefits and concerns about contemporary collecting

One of the core research objectives was establishing an understanding of the overarching public and professional perceptions of contemporary collecting. To achieve this, it is essential to understand respondent perceptions regarding the benefits of and concerns about the acquisition of twenty-first century material.

Benefits and concerns were the main focus of the open-ended survey questions. Responses from both public and professional participants to these questions revealed a more hesitant attitude towards contemporary collecting among many professionals, compared with the public, with professional responses containing an almost even split of benefit and concern codes. However, these concerns were mainly focused on the practicalities of contemporary collecting, such as issues with acquiring digital material, effectively preserving and conserving modern materials and the time-consuming nature of contemporary collecting. The uncertain long-term value of objects acquired in the moment was the most prominent concern among professionals, even though in the closed questions 83 per cent stated that contemporary collecting objects are able to maintain long-term value within collections and 76 per cent believed hindsight is not a compulsory element of collecting. Despite the prevalent concerns regarding the practicalities of contemporary collecting, the professionals also outlined many benefits, including future-proofing the collection, forming connections with the past and the ability to collect contemporary technology and developments. In comparison to the professionals, the public noted far fewer concerns (27 per cent of open-ended question response codes, compared to 48 per cent of codes among professional answers), but those that were raised included the potential neglect of historic material, the potential objectification of individuals’ narratives and uncertainty over whose voices are being represented.

The closed-ended survey questions further demonstrated significant support for contemporary collecting, with 88 per cent of professional respondents agreeing that the acquisition of contemporary material is a necessary practice, and a further 88 per cent of the public believing that contemporary material should be preserved for the future. Additionally, over half of both public and professional respondents believed that this practice was particularly important for STM museums. However, despite widespread support for this practice among the survey respondents, 39 per cent of professionals noted the presence of hesitancy towards the enaction of contemporary collecting among staff at their institutions. Furthermore, at least half of the 33 respondents believed that this hesitancy was visible in twenty per cent or more of their colleagues. This demonstrates that while professional hesitancy towards contemporary collecting is still prevalent, and reflected in both the open-ended and closed-ended survey responses, it is not a universal factor, as, in fact, this acquisition practice is widely supported by the public and professionals.

Support for this practice is further illustrated by acknowledgement of public interest in modern material. Professionals had a strong belief in the interest of twenty-first century material, with 98 per cent believing that contemporary objects in their collection were of interest to visitors. This contrasts the public, only 69 per cent of whom reported an outright interest in the displays of twenty-first century material in museums, with a further 43 per cent of respondents stating uncertainty regarding the likelihood of these objects to increase visitation. Nevertheless, when asked which type of gallery they would prefer, 89 per cent of the public chose one containing contemporary objects (with 22 per cent preferring a solely contemporary display and 67 per cent displaying interest in the juxtaposition of historic and current material). This suggests that while professionals have a slightly over-exaggerated view of public interest in contemporary material, there is a strong base level of visitor engagement with twenty-first century objects. Although interest is likely heavily dependent on the style of incorporation into displays and the topics covered, the significant presence of public engagement is a major benefit of contemporary collecting.

The research data has provided an overview of professional and public opinions of contemporary collecting. It suggests that although this practice lacks significant strategic focus and enaction in many museums, professionals have a generally positive attitude towards these acquisitions, despite the presence of hesitancy and concern among some respondents and other staff. The public also share this mainly positive view of contemporary collecting, especially when used to create a juxtaposition between the past and the present, illustrating change and development. This illustrates public support for the display of twenty-first century objects, but it is important to remember that not all contemporary material acquired by museums will end up on display. Nevertheless, public respondents strongly supported contemporary collecting as a methodology to preserve material for the future, an element achieved without the necessity for display. Alongside overarching discussion of benefits and concerns, three key topics – the importance of context, the issue of museum neutrality, and the presence of public scepticism towards contemporary science, emerged during this research. The next sections use these topics to bring together interview and survey responses, alongside relevant literature, to provide a more cohesive understanding of current perspectives of contemporary collecting.

The importance of context

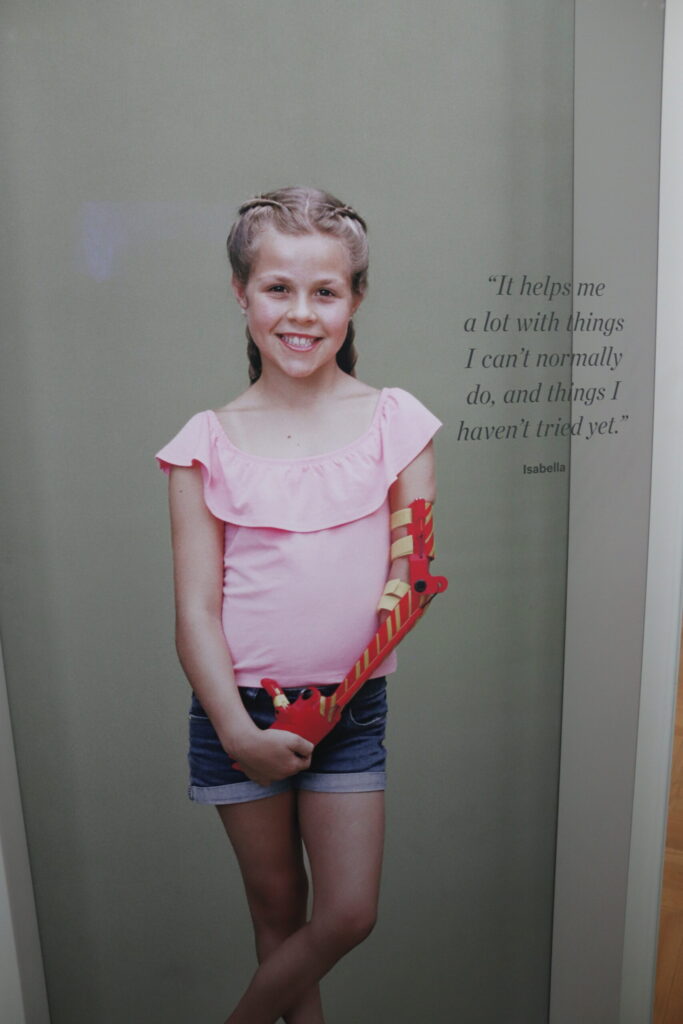

The ability to acquire contextual information or material alongside new acquisitions is one of the main benefits of collecting contemporary objects. This information can come in many formats, including images of the individual to whom the object belonged, written or oral histories about the item or associated ephemera. The incorporation of such additional material can aid in the ability of twenty-first century objects to ‘connect with visitors’, a major benefit of contemporary collecting appreciated by both the public and professionals (Alberti et al, 2018, p 402). Such acquisition of contextual material was heavily discussed among the professionals, with ‘context’ being the third most frequent interview code, and fifth most prevalent topic within the open-ended survey questions. This support focused on the ability to ‘capture contemporary opinion’ (Survey response, Q20)[4], as well as acquire extensive ‘information about the donor, about how it was used…the impact it had’ (Interview, 11 November 2019)[5]. Such knowledge provides these modern objects with ‘a good grounding within the collection’ (Interview 1, 19 November 2019)[6], enhancing the relevance and long-term value of contemporary material and therefore helping to future-proof the museum. Interview analysis also highlighted that the codes for ‘context’ and ‘display’ were one of the most prevalent areas of code overlap, demonstrating that they were often discussed together. This suggests that these two concepts are closely intertwined and illustrates the importance of acquiring and using contextual information for the efficient display of twenty-first century objects. In particular, 56 per cent of professional survey respondents noted the difficulty in displaying and engaging the public with visually incomprehensible objects, a concern which can be mitigated through the acquisition of contextual material, as illustrated by the Wonder Materials exhibition at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester. This display discussed the discovery of graphene in 2004, a difficult subject to illustrate as graphene itself is two-dimensional and invisible to the naked eye (Baines, 2018). However, to combat this issue, the exhibition incorporated objects from the scientists involved in the discovery of graphene, a decision which was highly popular among visitors, with audience survey data suggesting that ‘visitors enjoyed seeing personal objects in the exhibition’ (Baines, 2018). This technique humanises both the objects and the individuals behind them, enabling visitors to gain a deeper personal connection with the museum’s narratives.

While context is an important aspect of museum acquisitions and exhibitions spanning all time periods, contemporary collecting provides the opportunity to acquire a broader range of contextual material. By acquiring objects, and the surrounding contextual information, at the time of use, the risk of these memories being lost or ephemeral material being disposed of is minimised. By working directly with individuals to acquire personal narratives, and collecting material to situate STM developments and discoveries within sufficient context, museums can mitigate public concern that the inclusion of twenty-first century material ‘objectifies living people’s achievements’ (Survey response, Q38).[7] Situating objects in their contemporary context not only aids future research into such topics, but also helps combat this narratological concern raised by the public, enhancing public support for contemporary collecting through creation of an increasingly individual-focused narrative. The ability to interact with the people who use, developed or produced many contemporary items is one of the major benefits of contemporary collecting, noted not just by professionals but also by the public, whose interest in and support for the acquisition of twenty-first century material is demonstrated through their active involvement in collecting through ‘participation projects’ (Interview, 11 November 2019). In 2019, interviewees from the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave were discussing the involvement of the public through ‘Witness Seminars’, bringing together a group of people to collect narratives and objects surrounding a pertinent topic or event in science (Interview 1, 19 November 2019). At the same time, a similar practice was already well underway at the Science Museum, where participatory public engagement can be clearly demonstrated by the Medicine: The Wellcome Galleries display, which incorporates many personal stories associated with the collection and acquired through public participation projects. This is exemplified by Figure 5, which illustrates one of the many portrait and quote displays used within the galleries to highlight personal stories behind contemporary material. Such engagement of audiences in collection practices, alongside the use of contextual material, may increase pre-existing levels of public interest in contemporary objects in museums. This is because, as one interviewee highlighted, if contemporary items in a museum are affiliated with organisations, charities or individuals that the visitor has a close personal connection to, ‘even though it has been donated to the museum they feel that ownership and pride about an object being on display so that in itself encourages maybe people who wouldn’t have thought to come to the museum to see something’ (Interview 2, 19 November 2019).[8] While these positive affiliations may not be universal, as each visitor is building upon their individual life experiences, it illustrates the personal and social connections which must be considered and can be drawn on through the acquisition and display of contextual material.

Overall, this discussion has demonstrated that the acquisition of context facilitates achievement of the elements of contemporary collecting congruously supported by both professionals and the public, as it enhances display, encourages the inclusion of alterative narratives, enables future-proofing of the museum and has the potential to further public interest and engagement. By including objects from current society within museum collections and exhibitions, museums are encouraged to develop deeper connections, not only with product manufacturers and inventors, but also with their local community and visitors. This enables them to ‘create a meaningful record of contemporary times using lived experience of people living today’ (Survey response, Q20), adding an undeniable level of depth to their collection and presented narrative.

The meaning of neutrality

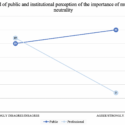

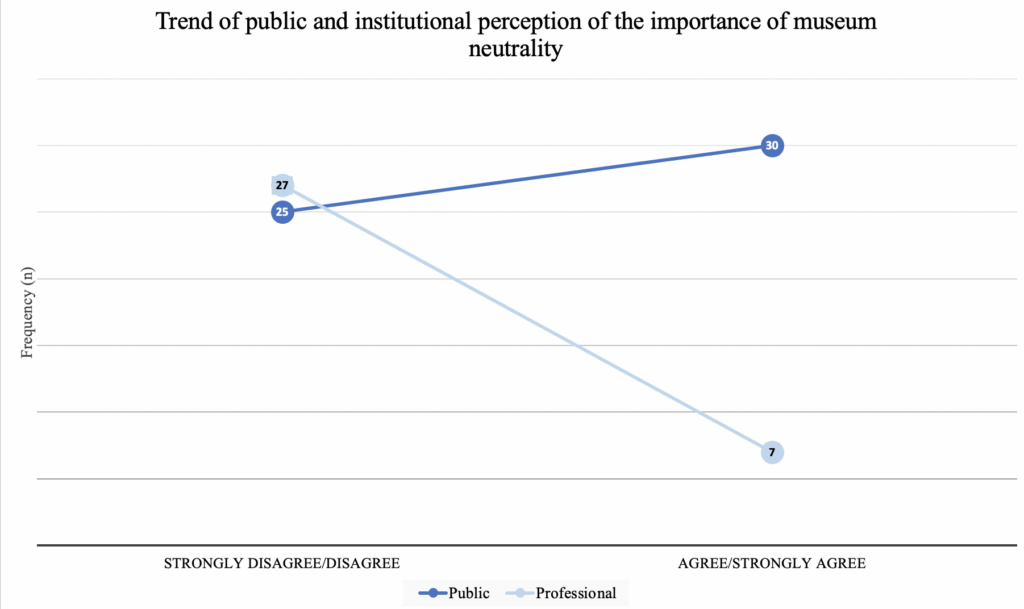

The concept of neutrality within museums is a complex concept to identify and study, and is particularly relevant to contemporary collecting, with over half of professional survey respondents (58 per cent) suggesting that neutrality can be harder to achieve when dealing with twenty-first century objects. It is clearly an important topic, and one that this research has shown to be an area of divergence between the public and professionals surveyed. Before analysing more specific survey and interview responses, the quantitative data was used to establish general opinions towards museum neutrality. This overview was created using a chi-squared test for independence into survey results for the statement ‘museums should remain neutral in all areas of information or discussion’. The test revealed a significant relationship between the public and professionals on their opinion regarding the importance of museum neutrality (X2(2, N=114)=10.06, p<0.05). Figure 6 demonstrates the increased public desire for museum neutrality, which contrasts with the professionals, who view museums as spaces without a fixed, neutral, authoritative voice.

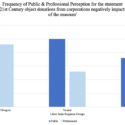

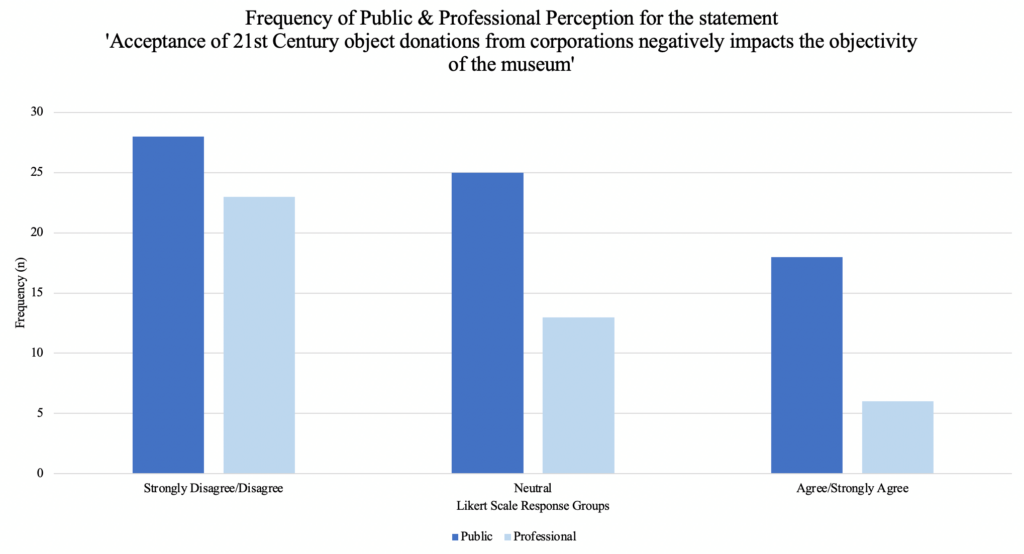

The concept of neutrality was further broken down in this research, with specific focus on the acquisition of corporate donations and items related to ongoing, and potentially changeable, research. This aimed to establish the presence of any concern regarding the incorporation of material relating to such changeable topics, or those representing companies who may have a vested interest in how their research is portrayed within museums. Interestingly, the survey results demonstrated that both the public and professionals supported the acquisition of corporate donations and ongoing research. However, this comes with a caveat that although 74.5 per cent of the public disagreed with, or were uncertain about, the suggestion that corporate donations may have a negative impact on a museum’s objectivity, 93 per cent agreed that these corporate relationships must be disclosed. This approach appeases the 75 per cent of public respondents who argued that it was essential for museums to provide objective factual information and neutral perspectives. The disclosure of such information was supported by professionals, 99 per cent of whom acknowledged the necessity of informing the public about certain areas of bias such as the presence of corporate relationships. This data highlights coherence in opinions between the two respondent groups, outlining support for the inclusion of ongoing research and corporate donations within collections of twenty-first century material, so long as they are clearly disclosed. This support is further emphasised by the second chi-squared test of independence carried out during this research. This demonstrated that there was no significant trend within the data to suggest that experience in museums impacts opinions surrounding the potential for bias within displays of twenty-first century material acquired through corporate donations (X2(2, N=113)=3.04, p>0.05) (Figure 7), again illustrating congruence between public and professional perceptions.

Even though, in general, public and professional opinions have been united in support for the inclusion of ongoing research and corporate donations within displays of twenty-first century material, the statistically significant variation on the importance of museum neutrality (Figure 6) raises some questions. It is highly probable that this significant difference stems from differing definitions of the concept of neutrality among both respondent groups. It can be reasonably inferred that the public desire for impartiality with museums stems from an interest in using twenty-first century STM objects to develop personal understanding of contemporary science, an objective which can only be achieved if they trust the information being provided within exhibitions and galleries. On the other hand, professionals are more attuned to the narrative that ‘museums are not neutral’ as they are constantly influenced by their social and historical context (ICOM, 2019). These differing approaches to the concept of neutrality are most likely to have contributed to the statistically significant variation in opinion.

Public perceptions of neutrality are central to this research, which demonstrates that even though the public believe objective and factual information is an essential element of museums, ninety per cent supported the inclusion of ongoing research despite the potential for fluctuations in results and uncertain future validity. This may suggest that such concerns over neutrality may be more tied to concepts of ‘unknown commercial and political forces at work’ (Survey response, Q38). This is further illustrated by a professional survey respondent who suggested that inclusion of objects with relevant current political associations could suggest that the museum is taking ‘a political stance which may alienate some visitors/staff/volunteers etc.’ (Survey response, Q21).[9] The concept of commercial forces involving themselves in contemporary collecting was well illustrated by Alberti et al (2018, p 409), who cite an example of acquiring an empty pacemaker shell from a company who believed this donation could be used to ‘promote their products for commercial purposes’, thus creating an ethical issue for the museum. However, while political stances and the role of the museum as an activist institution is a delineation many organisations are trying to understand, corporate interference is easy to mitigate, as outlined by many professional interview respondents, who emphasised that corporation-initiated donations would never be acquired for purely commercial purposes. Instead, such decisions rely on factors such as the collecting decisions of curatorial teams and the support of a rigorous collecting policy, ensuring that corporate incentives would never ‘be the driving force for the reason for a collection’ (Interview 2, 19 November 2019) and that objects are only integrated into the collection ‘if we think they tell a valuable story but we never make any commitments about displaying them’ (Interview 2, 6 November 2019).[10] This stance, supported by clarification to visitors within displays, where appropriate, can help mitigate concerns regarding neutrality among the public.

Furthermore, opening the museum up as a space for political discussion is not necessarily opposed by the public, as illustrated by the Museums Association’s research into the role of museums in society (Britain Thinks, 2013). This report acknowledged that even though the public did not believe that museums are the right environment for controversial debates, they supported the inclusion of these topics as long as the displays retain an air of neutrality through clear representation of both sides of the argument without telling people what to think (Britain Thinks, 2013, p 25). However, this report is dated, and support for the increased presence of potentially controversial debates and discussions within museums has increased, as demonstrated by this research, where 79 per cent of the public and 95 per cent of professionals supported the incorporation of debate and discussion surrounding culturally important topics within museums. While it can be difficult to establish clear boundaries when taking a stance on important topics, some museums are actively embracing this shift. This was illustrated during the interviews through discussion of the Rijksmuseum Boerhaave’s proposed plans to create a vaccination event in the museum for individuals to receive an HPV vaccine, enabling the museum to ‘take a stand for science, which I think is very important in the current debate with the fake news especially around a subject like this’ (Interview 2, 6 November 2019). The Science Museum in London put such ideas into practice and illustrated an effective way to take such a stand during the Covid-19 pandemic, hosting an NHS vaccination centre within the Museum in 2021 and 2022. These examples illustrate the multiple perceptions of neutrality which cannot simply be defined by numerical statistics, and provide an insight into why, despite the statistically significant disconnect, public and professional opinions may not be that diametrically opposed.

Although the topic of neutrality has significant scope for further research, this study has demonstrated that there is the possibility for unification of public and professional opinion in this area. While, from a professional perspective, neutrality may be harder to achieve due to the deep-rooted social and political associations of many twenty-first century objects, the shift away from ‘neutrality’ may also be linked to the ongoing transformation of museums, with professionals seeking to move towards increased integration of debate and discussion. This move towards an increasingly discursive structure is also supported by the public as long as their perception of neutrality is maintained, enabling visitors to use displays of contemporary material to build their own understanding of the world around them. This balance between debate and neutrality is highlighted by contemporary objects and topics and, although this research has provided an insight into perceptions, would be an interesting area of further investigation. While some museums may aim to present all sides of a debate as a way to accurately reflect important moments in history, as exemplified by the National Museum of Ireland, which sought to collect objects from both sides of the 8th Amendment referendum, others may choose to take a more defined stance (Malone, 2020). It is clear from this research that a large proportion of the public view museums as inherently trustworthy and while institutions may not agree with this presented desire for ‘neutrality’, they can create a stage within which discussions on complex and challenging contemporary topics can occur. By presenting information and using contemporary material to inform discussions, museums can provide a space for shared experiences, acknowledging emotions, experiences and influences which impact visitor perspectives, while also highlighting alternative views and possibly challenging public perception of the necessity of ‘neutrality’ within museums.

Overall, this research has demonstrated that while on the surface there does not appear to be congruence between public and professional opinions regarding museum neutrality, this is a strong avenue for further investigation. The public respondents to this research were theoretically open to the incorporation of debate, discussion and potentially changeable ongoing research in museums, suggesting that their aims may be more in line with those of the museum professional respondents than initially identified. Nevertheless, it is also important to remember that museums will not always want to take such an open stance on all topics, and instead make stronger statements regarding issues such as climate change. This research has only scratched the surface of public and professional perceptions of museum neutrality, and while it has identified general support for the inclusion of contemporary material, including those with corporate affiliations or associated with ongoing research, the concept of balancing neutrality and debate, an area particularly highlighted through contemporary objects and topics, is a key area for further research.

Contemporary collecting, education and scepticism towards science

One aspect raised within literature surrounding engagement with contemporary science is the public understanding of these developments. While public understanding of and trust in science is an ongoing area of research, a Pew Research Centre report from 2020 demonstrated that ‘scientists and their research are widely viewed in a positive light across global publics, and large majorities believe government investments in scientific research yield benefits for society’ (Funk et al, 2020). However, there is still some uncertainty, especially surrounding topics such as AI, automation of jobs in the workplace, genetically modified foods and the preventive health benefits of vaccinations (Funk et al, 2020). Museums can play an important role in this situation, providing visitors with the opportunity to investigate such contentious topics. By incorporating contemporary material, providing transparency surrounding their functionality, benefits and the research processes behind such creations, STM museums in particular can act as stages for development of visitors’ science literacy[11] and science capital.[12] This in turn may enhance their ability to situate themselves within our constantly developing society and decrease scepticism towards new scientific and technological advances. Among survey respondents, 83 per cent of professionals believed that such contemporary material could be used to ‘combat’ scepticism,[13] with a further 77 per cent of the public illustrating their desire to learn about contemporary STM developments within museums. Additionally, one hundred per cent of professional respondents believed that twenty-first century STM material can be used to educate visitors. This illustrates a congruence of opinion, supporting the idea that twenty-first century objects can aid the museum’s role as educator and enable visitors to situate themselves within the ongoing developments in STM, enhancing visitors’ science capital by providing opportunities for the public to learn ‘about new possibilities and how they will affect our lives’ (Survey response, Q37).[14] However, it is important to consider how these new developments are framed within the museum, as one-way methods of communicating science are not particularly efficient. Instead, institutions such as museums should be looking towards increasingly two-way, dialogue focused models of communication, acknowledging that opposition to scientific developments does not always stem from a lack of understanding but instead often relates to ‘differences in goals, values, or perspectives’ (Halpern and Elliot, 2022, p 624). Therefore, it is important to consider how such contemporary material is presented, ensuring consideration of the audience’s personal experiences and providing opportunities for increased dialogue and discussion.

The importance of providing a place to explore contemporary scientific developments was also illustrated through the survey. Whilst 95 per cent of public respondents believed that new innovations in STM were beneficial, 62.5 per cent were wary of or uncertain about increased societal reliance upon such developments. This illustrates the existence of uncertainties and concerns among the respondents. As mentioned above, while simple incorporation of contemporary material within exhibitions and permanent displays is a good first step, museums can provide the opportunity for audiences to develop their science capital and science literacy by actively stimulating debate and discussion. This is exemplified by the Science Museum in London, which partnered with Samsung for one of the Museum’s ‘Lates’ events to facilitate conversations around AI, encouraging visitors ‘to question how they felt about AI technology’ (Highfield, 2019). AI has the potential to revolutionise our society but, as acknowledged by Teg Dosanjh, former director of connected living for Samsung UK and Ireland, ‘the tech industry as a whole, have not done a good job at making AI understandable to people’ (Samsung, 2019). Therefore, by facilitating these debates, the Museum provided an opportunity for broader education on this topic by creating an environment where visitors could learn more about and voice their opinions on such subjects. As noted by one of the public survey respondents, this ‘ability of scientists to communicate with the public is…hugely important’ (Survey response, Q37), and the incorporation of twenty-first century material and topics within museums ‘can help people to maybe be quite reflective and I guess gain perspective on their position, whatever that position may be, within society’ (Interview 2, 19 November 2019). Inclusion of such discussion on contemporary topics may also serve to break down the all-knowing façade of the museum, potentially enticing a broader range of visitors who feel intimidated by this preconceived notion. This was effectively summarised by John Durant who suggested that ‘if ignorance and uncertainty come to be understood as preconditions for rather than barriers to research, then ignorant and uncertain visitors may be better encouraged to set out on the adventure of research for themselves’ (Durant, 2004, p 58). This illustrates the possibility for museums to act as a vehicle to further public understanding of science through the incorporation of contemporary scientific material and topics. Through an increasingly discursive structure, museums may be able to provide an environment for people to explore new scientific developments, a shift which would be supported by both public and professionals, on the basis of interview and survey respondents in this research.

Conclusion

Overall, this research, despite using a small sample size, has generated some strong insights into contemporary collecting which should be the subject of future research. Most importantly, it has demonstrated the presence of public and professional support for contemporary collecting in museums and highlighted the importance of this practice. Contemporary collecting not only benefits public engagement, but also enables museums to ensure their future validity by acquiring materials at point of prevalence and maintain their relevance by providing spaces for debate and discussion around contemporary topics. By incorporating contemporary material, STM museums have the opportunity to mirror societal interest in scientific developments, using contextual material to further humanise scientific research and provide a space for visitors to explore the ongoing and changeable nature of scientific procedures. The facilitation of such dialogue not only enables increasingly two-way forms of communication to be established, but also provides an arena for both the public and professionals to challenge perceptions of museum neutrality. This was a key outcome of this research, highlighting seemingly conflicting desire amongst public respondents for both ‘neutral’ information and debate or discussion, while professionals were increasingly keen to move away from this concept of neutrality. Although this research was too broad to investigate the specifics of this issue, it has highlighted a key area for future research, investigating the role of museums as spaces to debate and discuss twenty-first century developments, which in turn might act as a catalyst for visitors to question their perceptions of museums as ‘neutral’ spaces.

Furthermore, this paper highlights a gap in museological research, the absence of investigation into public perceptions of institutional practices, particularly contemporary collecting. Such research is highly important and can provide significant insight, enabling museums to strengthen their role in society through increased understanding and consideration of audience desires. Further research into this area, with a broader global sample of respondents and more specific definitions of neutrality among each respondent group, would be highly beneficial.

By increasing uptake of contemporary collecting, museums can provide an environment in which visitors can learn about and explore aspects of the constantly fluctuating and uncertain society around them. This shift can be facilitated through increased consideration of public interest and desires, as well as development of the museum’s own collecting plan and guidelines, enabling increased uptake of relevant contemporary material. By understanding the benefits of contemporary collecting, as well as some areas of disconnect regarding the topic, these areas of concern can be challenged and advantages of these practices become increasingly visible. Such acquisition of twenty-first century material could result in increased relevance, long-term validity and enhanced audience engagement. In conclusion, this research has provided insight into opinions surrounding contemporary collecting, illustrating the importance of public-professional perception research and emphasising the benefits of contemporary collecting for all museums, particularly those dealing with the constantly developing fields of science, technology and medicine. Additionally, it has highlighted areas for future research, investigation into which may serve to enhance and deepen understanding of the practice of contemporary collecting in museums.