In conversation: photographic curatorship and photographic cultures in museums and research institutions

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242208

Keywords

archives, curation, digital photography, photography

Introduction

Photographs have a habit of getting everywhere. Stored in their millions across institutional settings, these collections perform many functions as records, reference copies, works of art, and as scientific objects. Often, these boundaries are blurred and mobile, with photographs shifting between categories. The work that goes into cataloguing and organising photographic archives and collections is often invisible. The National Science and Media Museum is home to over 3.5 million photographs in its photographic collection alone, with many more in its other collections. Photographs can be found across the Museum’s collecting areas, and outside of curatorial categorisations within corporate records. These photographs have been amassed over a century, spanning from the inception of the Science Museum in 1857 to the founding of a major hub for science and media technologies in Bradford in 1983.

In this article, Curator of Photography and Photographic Technology, Ruth Quinn talks to Professor Elizabeth Edwards and Dr Costanza Caraffa, two leading thinkers on photography. As a historical and visual anthropologist, and former Curator of Photographs at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Professor Elizabeth Edwards has transformed perceptions of photographs as material objects. Dr Costanza Caraffa is Head of the Photothek at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz. Caraffa has developed leading approaches to the interaction between photographic, archival and academic practice, advocating for archives as places where research is generated, not only through the act of managing, categorising and re-categorising photographs.

In conversation

Ruth Quinn: I was musing on beginnings. Both the KHI and NSMM have a long history and are part of larger entities – how does this affect the formation of a photographic collection?

Costanza Caraffa: Maybe I can start by saying something more precise about the beginnings of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz (KHI). The KHI, as a research institute in art history, was established in 1897 in Florence by a group of scholars from the German-speaking lands – not from Germany as we think of it today, but from a broader geographical area, which had German culture and used the German language. The area had its own scholarly traditions and some momentum in institutionalising art history as an academic discipline. This was done partly by establishing the first university chairs in art history in the German lands, but also by founding new institutes, such as the KHI in Florence. The KHI was partially financed by the German Reich, then by the German Federal Republic, and it has been a Max Planck Institute since 2002. From the very beginning, the Photothek – the photographic collection of which I am the Head – has been part of the institution.

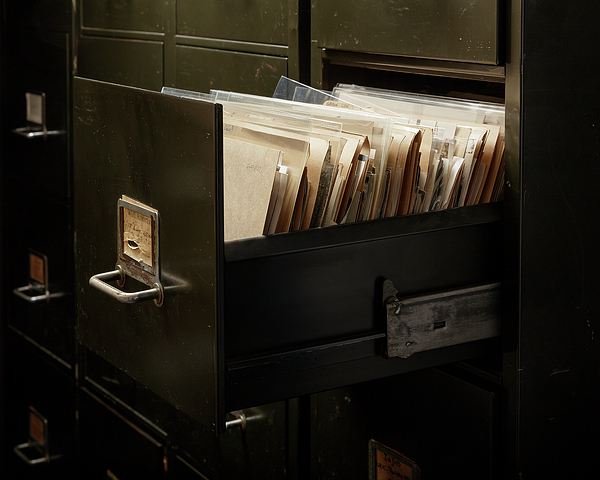

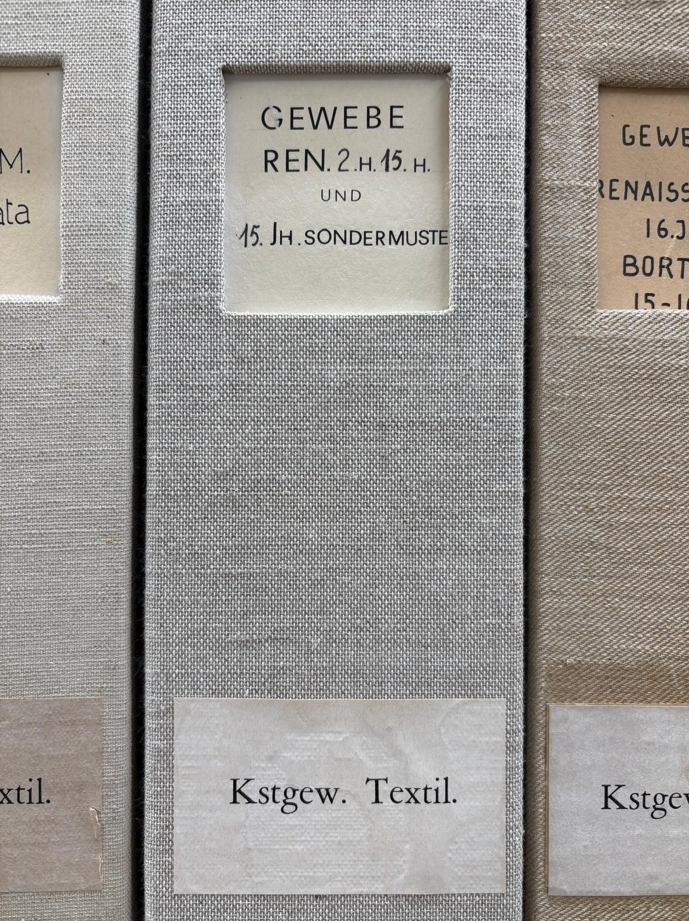

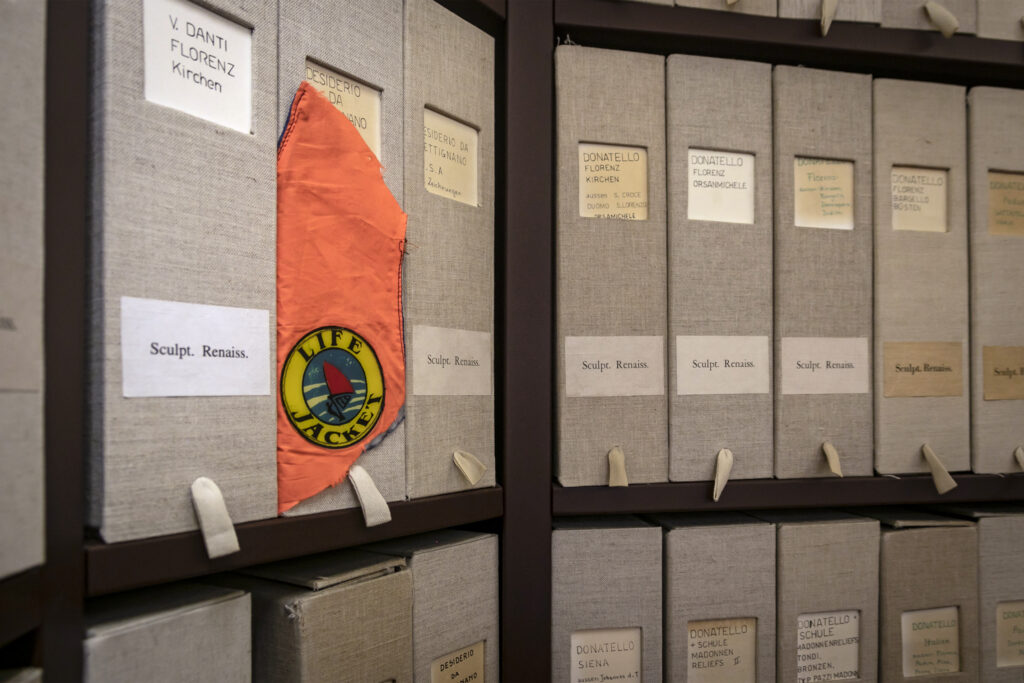

I do tend to use the German word ‘Photothek’, which I think is understandable in English. I don’t much like the English translation ‘photo library’, which recalls the idea of photographs like books that you can pull from the shelf so that you get exactly the information you are looking for. This does happen in our collection. In fact, we have boxes that are classified using a certain system and you can go to the shelves and pull out your box and find your photographs. Yet, we prefer the definition of a photo archive which contains all the dynamics that are part of our work. So, although Photothek, exactly like Bibliothek, can mean photographs from the shelves, the idea that we are an archive and not just a photo library is important. For us Photothek is a conceptualisation of the long history and the many potentialities of this accumulation of photographs over almost 130 years.

Elizabeth Edwards: Yes, I think many photographic collections outside fine art are almost accidental in that they are deeply functional and have grown around other practices of an institution and its research agendas over time – as in the case of the Science Museum Group.

I should explain my connection to the Science Museum Group and to photography. I have been a colleague of the Group of very long standing, using the collections, communicating with curators, but I have also been a member of the Advisory Board at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, for which I’ve just finished a nine-year stint. So, I have very close connections with the Science Museum Group, although I don’t pretend to speak for them. For me the Science Museum Group has a key conundrum, in that it is a Museum of Science and Technology which has always collected photography, but which hasn’t always recognised that photography in the way that we recognise it now. This happens in all collections, that things shift categories rapidly. I hate the stereotype of the dusty archives – archives don’t sit still long enough to get dusty! Also, although the Science Museum Group collects the technology and science of photography, inevitably it collects its product too and that produces another set of problems: how do you position that within the institution?

Most of my curatorial experience was as Head of Photograph Manuscript Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, one of the world’s major collections of ethnographic material, which faces similar issues. For example, photographs there were of peoples of the world, or technologies that were too big or difficult to collect – buildings and boats, for instance – or intangible culture such as rituals, or religious sites. Consequently, photographs are filling the space in other collecting patterns.

I always like Stoler’s (2009) idea that there are two ways of approaching an archive. You can do it archaeologically – just digging out facts to use – or you can approach it ethnographically, as a system or culture to be understood.[1] I think this latter approach is what Costanza and I have in common, we’ve discussed it for decades now. Why is material there? How is it perceived to operate? How has that shifted over time? How do we deal with those [shifts] at a curatorial level?

Costanza: We often use archaeological methods, or philological methods, but it’s also important to me that a new ethnographical approach doesn’t cancel the original mission of a photographic collection providing, say, photographic documentation of the history of Italian art and architecture. It is not a shifting but an enlarging of the possible functions. We still have users coming because they need the photographs for more traditional use. This raises the topic of the assumed objectivity of photographs and of archives.

Rhetorics of objectivity arise towards the end of the nineteenth century. The manuals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries underline the presumed objectivity of the archive in the same way that early photographic texts underline the objectivity of photography. It is interesting to see how this rhetoric is still active today for many of our colleagues who are not photography or archive experts.

Elizabeth: What you say about how it’s not a shifting, but an enlarging of archival potential is really important. One thing that interests me is how the shift is not just in the archive, but it’s also in the questions that are being asked of [the archive], and in who is asking those questions. This is certainly so in anthropology museums. I suspect it applies equally to collections like the Daily Herald archive in Bradford, where just as we’re starting to think about disciplinary and curatorial subjectivities that have made an ‘objective’ collection, other users are coming in who want that truth – that objectivity of the image.

In many cases that I dealt with over twenty years, people wanted photographs of ancestors: they wanted the ‘truth’, the proof – ‘We were there, our land was there, therefore our spirits were there’. That becomes a sort of objective strand based on the indexical truth of the image. This is the basis of work on decolonisation, although 30–40 years ago we called it restitution and equitable access. It’s putting different demands on collections in very positive ways.

Costanza: I completely agree with you, Elizabeth, and for us too there is a shifting in the way we look at this material involving an enlarging of our job as archivists.

We are now thinking about our role in a broader sense, believing that we don’t just preserve photographic objects and photographic documents for future generations of researchers, but that we also produce and transform them. The collections are shaped by us and were shaped by our predecessors. Generations of archivists apply and adapt similar rules over time – Joan Schwartz and Terry Cook would call them scripts (2002) but there are also changing perspectives.[2] There has been a huge shift in how to look at these documents in the last twenty years.

Elizabeth: Isn’t materiality at the centre of that? You’ve done so much work on that.

Costanza: Yes, it is about materiality. It is realising that photographs are not only flat images but material, three-dimensional objects existing and acting in time and space, in social and cultural contexts. They bear traces of their different uses, from the moment in which they were taken and printed with a specific technique, by a specific photographer, for a specific (commercial, scientific or personal) purpose up to their arrival into an archive. Here they go through successive transformations. Photographic archives are more than the sum of the images stored in them. They are dynamic organisms – Elizabeth and I call them ecosystems, in which not only photographs, but also inventory books, mount boards, card catalogues, digital records, classification systems, and finally human agents, such as archivists and scholars, act and interact. Most of what I am saying I’ve learned from you, Elizabeth, and Joan Schwartz, so it is a little bit strange to say these things to you here![3]

My approach was formed also by a shift within my institution. The KHI was impacted 15–20 years ago by the material turn, which came to art history a bit later than other disciplines but was very strong at my institute. Research at the KHI has developed in innovative ways, opening up art history to other disciplines, and to the decolonial approach. I’ve been very lucky to have so many inputs leading to a shared agenda. I had started to look outside art history, towards anthropology, archive studies and exploring decolonialism, but the dynamic within the KHI helped me to find my own approach that has firmer foundations because it is embedded within and outside the institution. This mixing of the material approach and the postcolonial or decolonial approach has been very important to me, it helps to disrupt existing mental hierarchies.

If you focus on photographs as objects, a central question of whether the photograph is only documentation or a work of art becomes completely obsolete.

This question reproduces hierarchies that have dominated art history and is rooted in the idea of the artist as author. One easy way to satisfy this question would be to ‘upgrade’ one part of our photographic collections as works of art. This can be a demand, not at my institute, but it is a very common way to think about photographic collections. For me it is an extractivist process: where you extract from the masses the most beautiful photographs, ‘museumise’ them, and forget the rest, which I don’t feel is very productive.

Elizabeth: This is where ideas coming out of anthropology in the last twenty years can help, because I think a lot of the problems is this pressure – from the whole system of photography, down to collections management software. Everything is predicated on the single object – if you’ve got a canoe from the Sepik River in Papua New Guinea, you have a canoe from the Sepik River. There is no question about what it is. That object has different meanings for different people, but it is what it says on the label.

You can’t say that for a photograph. Which has so many meanings and formats – I have even seen a stereo card pair cut in half so there are two photographs that look broadly the same but are in different boxes doing different things. Or they’re stuck in an album, or they’re turned into a postcard, and it goes on and on.

I’ve found the most useful way of thinking of this mass of photographs is Alfred Gell’s (1998) notion of the distributed object. He uses a dinner service as the example.

A dinner service is made up of plates and gravy boats and side plates and so forth. There are individual objects that have their own history and biography, but are part of a larger whole, a dinner service. We can use this idea fruitfully in the way we think about how photographs work – photograph of whatever is distributed through these various forms with different life histories, but it belongs together in a set as well.

The battle we’ve got is that many museum systems don’t allow for this kind of thing. They allow for supporting documentation, but how do we account for the other 340 versions of this photograph? Networked seriality needs more thought than we tend to give it. The traditional art historical model that Costanza’s just talked about – privileging authorship, uniqueness, the preciousness of the object, the quality of the print and so forth, are meaningless in collections like this. If we take out one image, on a 35-millimetre roll, what about the other twenty? What you’ve got is a form of seriality – we have to think more seriously about this in photo collections. It might mean that we sacrifice precise image content description, to look at a series of images that are complementary and tell a narrative together. There are methods out of film curatorship that we can look at, but it’s about bringing objects together.

The other concept I find useful is the idea of the multiple original.

While there’s always been an archival focus on the negative as the originating moment, beyond that it’s an open field. How do we cope with that primal one-to-many relationship and go beyond it? There’s the many-to-many relationship and it’s our distributed object we need to deal with, not just in practical terms of coping with databases (and I’m no longer a practicing curator, I haven’t been for twenty years, so I’m sure everything has changed). Ruth, you’ll be able to tell us, but for me it feels that there’s still this focus on the content of the image.

I’m not pretending archaeology isn’t important. How do we deal with those other layers that make photographs work in the world? I always say that mass photography changed more about how people saw that world, thought about that world and therefore acted in the world than just about anything else. When we come to display photographs in museums and galleries, we should get away from this square frame on the wall. We need to show them as social objects. Your exhibition Unboxing Photographs. Working in the Photo Archive that you did in Berlin did that,[4] Costanza, it was brilliant.

It really showed these images at work. The narrative of their social activity, their cultural activity was so strong. It really was a brilliant show. And I think, that’s the way forward.

Isn’t Bradford trying to do this with the new Sound and Vision gallery Ruth?

Ruth: Yes, the new galleries will do that.

We’ve moved away from having one floor per disciplinary area. Where previously we had animation, film, television and photography all separated out across the Museum, when we open our new galleries (in 2025) we will have integrated those technologies.

We are a museum of multiple technologies and we want visitors to explore the integrated nature of media not just from a contemporary perspective, but from a historical perspective. It was interesting to hear what you were saying, Elizabeth, about collections management systems, because for me one of the big challenges is that they don’t change often. Whilst you can make small changes to a system, on the whole they are quite static and that affects how collections are managed. For example, we use one system for objects and another one for archives, so we have to ask ourselves what makes a collection of photographs objects or an archive?

Something we’ve been thinking about a lot is how photographs require an archival and records management approach as well as an object approach. Historically we’ve sorted our collections into photographic technology and photographs alongside the library and archive collection. However, as photographic collections don’t always fit easily into one category…you have to adapt systems, in order to catalogue distributed objects, like photographic albums, in a museum object categorisation system.

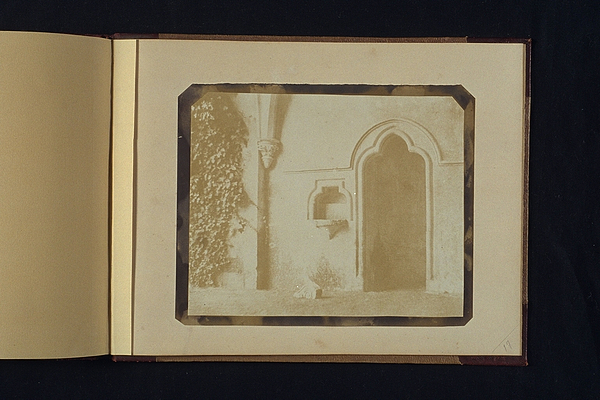

On the subject of multiple originals, I was thinking about the Talbot collection; as a collection that is distributed across institutions. We’ve got material related to Talbot but the V&A also has material, as has the British Library, and again you think about originality with a collection like that. We have got the oldest known surviving photographic negative, but it’s difficult to describe as a ‘first’ because negatives are not singular objects. Talbot and his contemporaries made many ephemeral, experimental negatives, we just happen to have the oldest known surviving example.

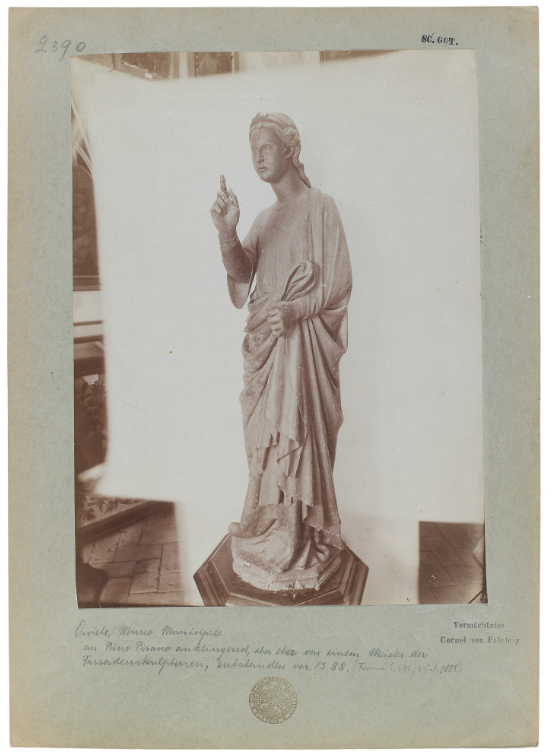

Costanza: I would like to come back to your previous comment, Elizabeth – you are completely right. Thinking about multiple originals and going beyond the uniqueness of the object is vital, yet often the only way to come to terms with the masses is to focus on one single object. This doesn’t need to be an exceptional one, as for instance a print by Talbot. Thinking in terms of photographic objects helps, among others, to emancipate the archive as a whole from traditional hierarchies of value. We as historians don’t have to necessarily focus on a recognised museum-class object. We are free, rather, to spotlight photographs that seem to come from the margins and lower rungs of the collection. Perhaps a clipping representing an obscure work of art, pasted on a cardboard with almost no inscription, showing only a few hints. Yet, if you do a serious ethnographic and archaeological research within the archive, this apparently anonymous and unspectacular photographic object will start to tell its stories.

In the end you come back to the archive because in telling this story you say something not only about the original context of that photograph, but about its archival history as well as about archival practices in general.

Elizabeth: I think Costanza is entirely right. It’s that historiographical methodological question: how do you validate your case studies? Yes, one does focus on one very small body of photographs or a single photograph as a carefully selected case study which can speak to multiple historical questions.

What worries me is the way that photograph collections are often used in illustrative ways, and that the detailed contextual work that Costanza has talked about simply isn’t done.

Why does this happen to photograph collections and not other forms of multiple original collections? There’s something very deep seated here. Is it the ubiquity of photographs that somehow mitigates against this? The multiple original is not exactly a new idea for museums. Museums have been dealing with multiple originals for generations – for instance, in collections of medals and prints and engravings. All these people who spend a lifetime peering at different pulls of a Dürer print, they’re dealing with multiple originals, so why is this concept suddenly so difficult for scholars to grasp when it’s about photographs?

A lot of twentieth-century history of photography has been written for the art market. This has caused us methodological problems across institutions that are not collecting like that. Photograph collections remain marginal – both Costanza and I can tell horror stories about the risks of this, which is why Costanza started the Florence Declaration on the material archive, there’s this idea that somehow [you can] digitise everything and chuck the rest out; that somehow digital is the cure-all panacea because it gives access.[5] But access to what? Unless you’re fully catalogued, it’s giving access to ignorance. I’ve heard the argument that ‘it solves your storage problems’. No, it doesn’t. A standard silver print from the nineteenth century, once it stabilises, is pretty good for a hundred years or so. Whereas we all know that electronic data disappears after about five or ten. So the arguments put forward are completely spurious.

We went through this with microfilming. I’m old enough to remember when the men in grey suits and the clipboards said, “We could micro-film all this and then you won’t have conservation problems.” And we thought “Mm-hmm.” Then we got a reprise of the very same argument around digital. I see this as one of Walter Benjamin’s ‘moments of danger’ (1940) where history flashes up. The history of materiality and the possible destruction of these functional collections that nobody really cares about is at stake, which is how Costanza and I feel.

The materiality argument became important because it was a backstop against this ‘Digitise and Chuck it School of Management’ thinking. Costanza did so much brilliant work in this field, and changed the way that archives have thought about photographs over the last ten or twenty years. Even if it’s nursing care only, in a box in a controlled environment, you don’t throw it out. The work that’s being done in all our collections is showing how important the material object is. This is an essential argument against the dissipation of our collections. It’s our responsibility as curators and archivists to ensure that our collections are there for the questions that will come in the future, when we don’t know what those are. If you told me forty years ago I’d be sitting on a Zoom call defending the object and the photographs I wouldn’t have believed you, but I’ve done it a hundred times, as has Costanza.

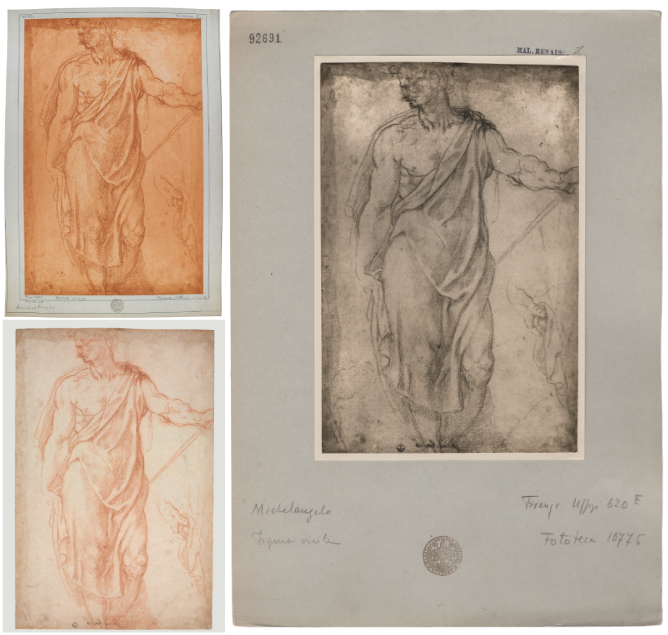

Costanza: Still, there is a new understanding, and digitisation practices are not so basic and brutal anymore. Now it’s accepted that you digitise the entire cardboard and not only the photograph – the back of the cardboard too, if there is information there, and card catalogues or inventory books and so on. Still, digitisation will never give you the same kind of information. Historians know this well from book editions of documents. For my research I’ve consulted countless books in which all the letters and documents concerning a certain work by Caravaggio are published. These documents are exactly transcribed, but the clue came not from reading a book but by going to the archive and reading the same words in the original document. It is different. It matters if it is a huge piece of paper, if it is good paper, or if it is just a little booklet, what is written on the page before or after a particular text and so on. It is the same for photographs. You can do other forms of research in digitised collections – you can put together metadata for instance, but it is not the same, it is something else.

Elizabeth: Exactly. It’s not the same thing. I find digitalised collections brilliant for a first stop and an aide memoir, but there are many problems. Yes, digitisation projects are much less brutal and basic now, but because of the way funding works, if a collection were done fifteen years ago, it’s going to be decades before it’s done again with more sensitive digital procedures.

We’ve got a backlog where digitisation has been done in what (by modern standards) is a pretty basic way and it’s not going to be done again. Also because of the way the funding works, digitisation is done on conventional topics. Going back to anthropology, it was relatively easy to get the money to digitise important collections from Tibet because it has a high profile – the Dalai Lama is a very important global figure; it had intellectual ‘street cred’. It’s not as easy to get money to digitise work from, for example, Sudan or Chad, because they don’t have that heft in Western art history, travel, writing or popular culture.

I also wonder if digitisation projects are indeed complete. I suspect they force some material to the top of the historiographical heap and because so many people work online now, that’s what they’re going to find. Albums are done and there’s three stray photographs interleaved at the back that are left out because they don’t seem to fit, so they disappear. What is digitised is good material, but as Costanza says, what about the rest? I was talking to the head of photography of a major collection – this is about ten or fifteen years ago – they’d digitised a certain part of the collection there. I thought – I’m very pleased you’ve done it, but it seemed a strange choice given the riches of that particular collection. When I asked why, the answer was “Oh they’re all the same size. We could do them quickly and reach our digitisation targets.”

That collection now almost dominates the website of the very important larger collection, but it’s not the most important part of it. So digitisation programmes can skew the historiographical value attributed to a body of images. I know this is a big thing in Bradford, Ruth, with the Daily Herald [archive] which is so huge.

Ruth: Yes, that’s a really good point, Elizabeth.

As a national museum we need to be led by our audiences, and local audiences are a big priority for us. The Daily Herald Communities & Crowds project is a good example of how we’ve started to think about digitisation led by our community. For this project, we invited members of the community in and said, what are you interested in? Then we digitised the photographs that they identified – images that spoke to the experiences of a group of people in Bradford with an interest in the African-Caribbean Community. It’s important for people to be able to locate themselves in our collection. A lot of people don’t know, for example, that we’ve got the Daily Herald archive or what the Daily Herald archive is. It circles back to what you were saying before, Elizabeth, about people finding themselves within collections.

It’s important for people to feel that the collections speak to their community and culture.

How do we tap into those personal connections as well as all the digitisation priorities we have, led by research interests and grants? I wonder whether moving towards that personal journey might be a better way of driving digitisation. People can come in and look at the photographs – the digitised version is not an alternative to the physical object, but digitisation expands access given not everybody can visit, and it means we can connect to communities around the world.

It was interesting to think about your points around the history of digitisation. If we think about digitisation projects done twenty years ago, what is the quality of that image file now? We need to be thinking about how we archive our digital preservation practice.

This is a challenge now because we need to catch up with digital preservation. We risk losing work that’s already digitised because it is often dispersed. For example, if images from a digitisation project are held on a third-party website which is managed by a university, and the funding runs out for that project, who looks after that resource? It needs its own kind of preservation model.

Elizabeth: I agree. One problem with grant funding is that there is hardly ever aftercare so when things start going wrong, useful resources disappear. I’ve had experience of a university project which digitised in old software and is now just a weak link. The software becomes vulnerable to hackers and the universities take it down. I can understand that in security terms, but when we say, can you transfer it into something else for us they say, where’s the money? There isn’t any. Project aftercare is urgent and I’d like to see funding bodies putting aside money to update systems so older digitised resources don’t get lost.

To go back to Ruth’s point about people being invested in archives, This has been a driving force in collections of anthropology and ethnography for decades. One thinks of the wonderful work done at the Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, under Anita Herle with Torres Strait Islanders. The objects have been photographed, the photographs have been scanned, they’ve been exchanged and deposited for educational purposes in high schools in Torres Strait. It’s a textbook example of a long, committed, involved relationship, which opens a collection to the communities where it should be.[6]

That’s something we have to ask the whole time. Where should our collection be? And often, as Ruth’s said, it’s out in a community, working hard, and fortunately with digital technologies we have the wherewithal to do that. That’s an exciting development made possible by developments in technology over the last twenty years.

Costanza: On the other hand, there are huge problems that we should mention such as digital retouching, which is often done with the idea of restoring the photographic image but it obliterates the photographic objects with its traces of use and time.

I was in a collection that is part of a top-level university in the US. They showed me how they were digitising negatives from the archive of a photographer. These had been kept in folders, so they had the punch holes in them. By applying the precise guidelines of their university, they were erasing the holes – which for us is unthinkable, but this is done.

We could also talk about databases: we started with the idea that archives and photographs are objective, but nowadays there is a frequent idea that databases are objective. Here the new debate about artificial intelligence comes in, but the data comes from somewhere and involves a string of decisions.

Elizabeth: I think one of the things that needs to be thought about broadly is how we teach researchers about using original resources at any level: in schools, and in universities so that students understand that it’s algorithms determining what you’re going to see. I don’t think this is widely taught at a critical level, particularly as it relates to photographs. It seems to me that a lot of critical historical methods go out of the window when people start looking at photographs.

How do we reinsert source criticism and a critical eye into how people approach digitised collections of photographs? I completely agree with what Costanza has been saying, that digital seems to be the only thing that people will look at.

I remember a student coming to me and saying “I’ve been working on this and I can’t find anything online.” I said that I happened to know that lots of nineteenth century vicars wrote about this and it’s all hidden in the transactions of local history societies.

They looked at me as if I had assaulted their human rights, to suggest that something wasn’t online and they needed to go to an archive.

Okay, I’m exaggerating a little…but I think we need to manage that kind of expectation of what kind of resources are available online and that they are only the first stop. When an archive tells me everything’s online, I know that the ‘uninteresting’ bits have been left out. Even if it is online, I still need to see the original, for reasons Costanza has described. It’s very frustrating and it goes back to this fundamental misunderstanding of what research and photographs do together.

Costanza: I wanted to pick up something that you were saying about needing to train people. It is also important to do this at a small scale. KHI is very different from the Science Museum. We are quite a small research institute, and we don’t reach huge audiences, but we have a trainee programme. Each year, eight students, mostly from German universities, do a training at the Photothek and they go back home with a new way of working and understanding photographs. And we run seminars about historical photo techniques for the fellows of our Institute. Participants come from different kinds of research project, most of them not about photography, but they leave with their minds exploding with new ideas. Just from attending practical training for one day, they will read any photograph in their own research in a completely different way.

I think there’s a lot of value in this low level of spreading new ways of looking at photographic material.

Elizabeth: Well, that sounds wonderful. We live in hope. It would be wonderful if you could do 800 a year [everyone laughs].

I do think it’s important to train people who are not working on photographs because they’re all working with photographs. This comes back to something Ruth said about how we archive our own procedures. Because photographs are central to museum practices, so how do we archive our own history and practices? You can’t archive everything. We’ve got enough problems with the non-collection management photographs, but I think one needs to foster an awareness amongst researchers and curators about how photographs are shaping what they do in their day-to-day work. For the book I edited with Ella Ravilious on the V&A collection (2022) we interviewed photographers about shifting styles in photographing one object, showing that how the supposed objectivity of the museum photograph is much more subjective than one might imagine.[7]

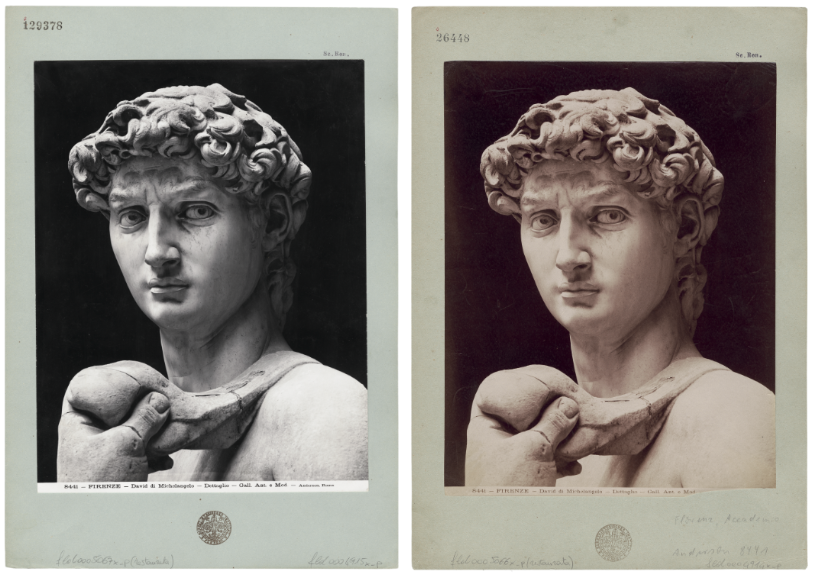

One just has to go to Costanza’s collection and see the different ways something has been photographed over the last 150 years, including its digital manifestations, to realise that these are profound acts of translation. To approach them as a true document is quite foolhardy. So, something else we need to think about is our own shifting ideas of what an object photograph in a museum should look like.

One of the things I wanted to do at Pitt Rivers was an exhibition about the shifting styles of object photography within an institution, and everybody would roll their eyes and say, “Oh, boring. No, we’re not doing that!” But some of Costanza’s work – I’m thinking of the Foto-Objekte exhibition – shows how wrong that is.

A lot of institutions are beginning to look at their internal photography and their own collecting. In Paris a couple of years ago, there was a wonderful 2019 exhibition, Foto Buch Kunst, at the Albertina in Vienna.[8] It looked at technologies of reproduction, the aesthetic and technical, in that relationship between the book and the photograph. It was fascinating.

I think institutions are getting interested in their own photographic histories as a practice. This is another way of bringing people into thinking about the institution, what photographs are doing there. It’s a reflexive critique from within, but it’s also an insight many people find fascinating about how museums work.

Ruth: Should we have a chat about classifications and thinking about how we activate and reactivate photographic collections?

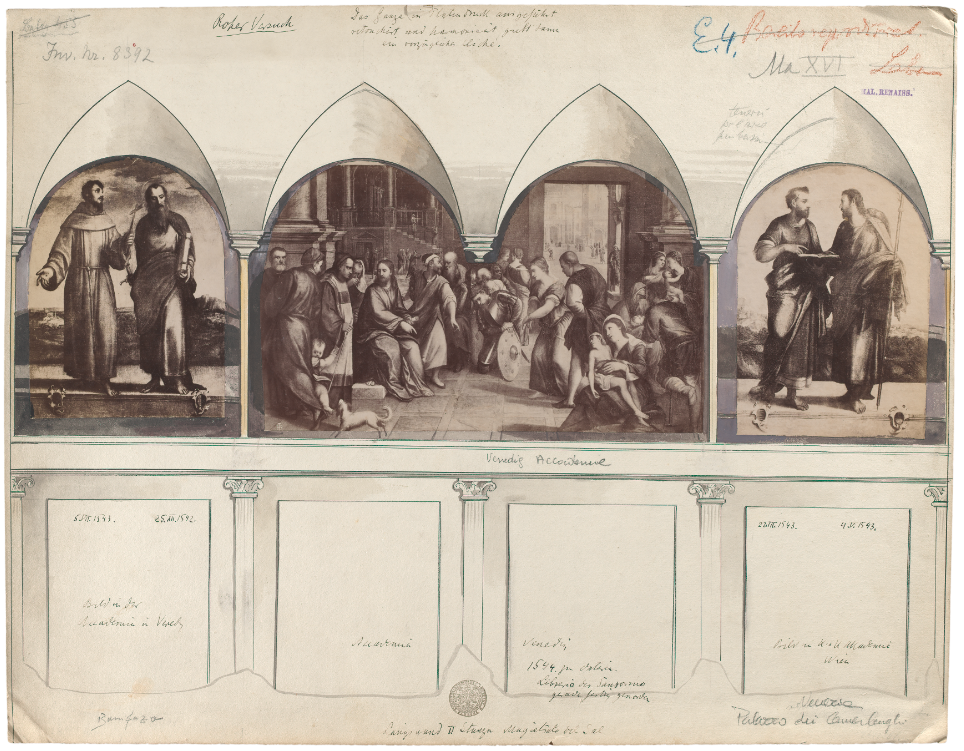

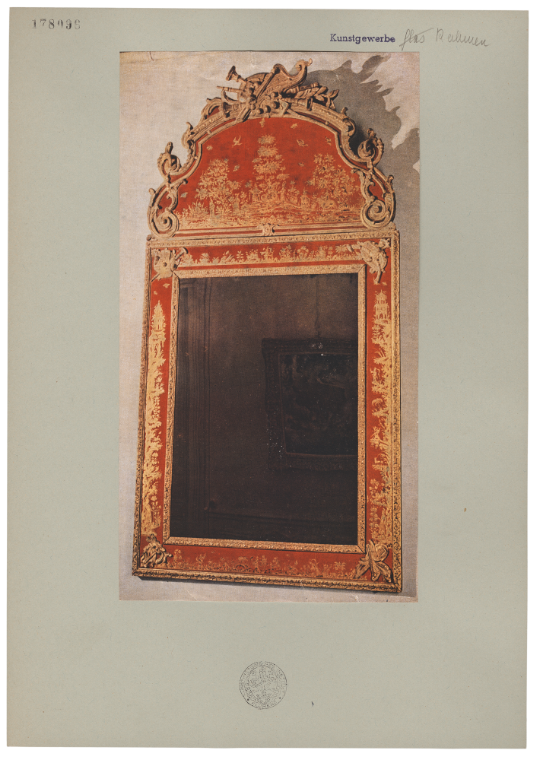

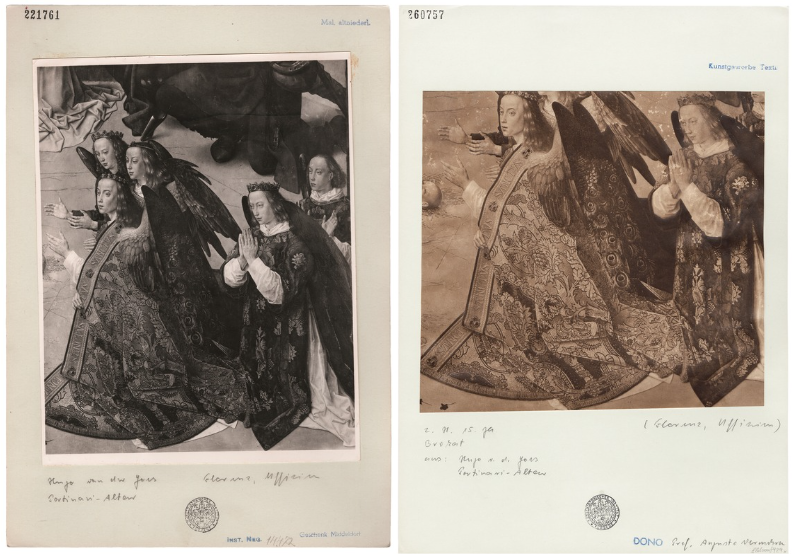

Costanza: Classification is very important because it reveals how a photographic archive or collection or museum is constructed. It is an angle through which to observe the way the holdings are suggested for specific uses and not for others. There is the affordance of the photographs we collect, but also the affordance that we produce – a new affordance in which we put the photographs in a certain order in a certain box and not in another. We have photographs representing the same object that are put in different boxes in the collection and in each case you can follow the logic of the archivist. Because we have the inventory numbers and the inventory books, we can even reconstruct a temporal succession. Let me give an example: a photograph of the Portinari altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes in the Uffizi in Florence came to us in 1925 and it went in the box of early Dutch paintings. Then, a detail of one part of this altarpiece, showing the family of the donors in wonderful clothes with brocade, gold and embroideries, came to us some decades later. This detail was put together with the photograph of the entire altarpiece in the same box. A couple of years later, a similar detail of the same altarpiece came into the collection representing the same detail of the painting. We imagine that our predecessors had a look at the box of early Dutch painting, saw that there was already a photograph of this detail, and thought a second image wasn’t needed. Instead they put this second photograph of the same detail in a different box, ‘Applied arts, Textiles’. It thus becomes a document of a second grade, a document not of the painting, but of clothes of the fifteenth century represented in paintings.

This is something so interesting. We have the wonderful opportunity to reconstruct the temporal levels of these operations. Although we critique this classification system, including from a decolonial point of view, we still have to put new photographs in boxes every day – we have to use some classification system. It’s so interesting to see how this system develops. This seems at first to be a discourse about the structure of the archive as a manifestation of power. It is. But it is also a discourse about the agency of archivists who apply those rules, and in doing so produce shifts and, as Elizabeth would say, points of fracture.

Elizabeth: [laughing] Yes, I very much agree with that. I get irritated when I read statements like ‘History begins when historians open the archive box’. No, it starts when the archivist puts something in a box. That’s when the historical interpretation begins.

I wanted to say something more general on questions of classification and language. The language that we use in cataloguing and object description are absolutely crucial, because those are our pathways in.

Language is central to the decolonisation or ‘whole histories’ debate. For example, if you use categories like magic rather than belief you are making assumptions that frame access in certain ways. The language of classification produces objects as certain kinds of things and not other kinds of things, to the extent that the language of classification and of object description is the consciousness of an institution at work, so we need to think about it in very critical terms.

It’s very difficult to do retrospective language improvement within collections. It’s an enormous amount of work. I know institutions who are engaged at the moment in removing certain forms of language and description from the catalogues as a kind of equitable curatorship, and rightly so. But it is an enormous job because you can’t just do a global change on a database because you don’t know the context of that word.

Costanza: We are confronted with wording that is not just problematic, it is insulting. We consulted our card catalogue together with Lebohang Kganye, an artist from South Africa, who we are working with. We saw that ‘slavery’ in our iconographic catalogue is given among professions with ‘sailor’, ‘butcher’, and so on. This is of course, insane. But what should we do? Should we remove that card from the iconographic catalogue? I think it would be better to do something with it so it may become a part of a work of art, or we might draw attention to it in an article. We are a small institution so we can speak directly with our users and prepare them for this kind of encounter. We have to be aware about language, but I don’t think that it would be good to remove this historical source entirely.

Elizabeth: I would never advocate getting rid of historical interpretations and the language of them. They need to be managed further down the data. One problem with historical data, particularly as people search collections online, is that the first encounter is usually a headline description of an object or photograph and that is taken as the institutional consciousness when it is often not, nor should it be. That’s why it’s very important that language is addressed, because not only is it offensive in many cases, but it also misrepresents what the institution is trying to do. It’s very important that we manage those layers of historical information, but we must never destroy them. You’re quite right.

Costanza: Yes, I would never put something like this online. But for people coming here, they would encounter also this kind of thing.

Elizabeth: For me the major thing is to make people – the public, scholars, everybody – aware of what a well-managed photography collection can deliver. At many different levels I think they’re very active as they are. But we’ve got to find strategies for making them seem to be active – as we said earlier, making people feel that they own parts of the collection. If I were curating now, and I know many colleagues who still are, this is a priority for how we position our collections in the wider world for the greatest possible good.

Costanza: Yes, I completely agree. In a certain sense, thinking about the Florentine Photothek, it’s more difficult when you deal with objects that seem not to be very connected to our contemporary world, except for the fact that millions of tourists still come to Florence every year to see this wonderful city. One important aspect that is not perhaps obvious, is activation through research.

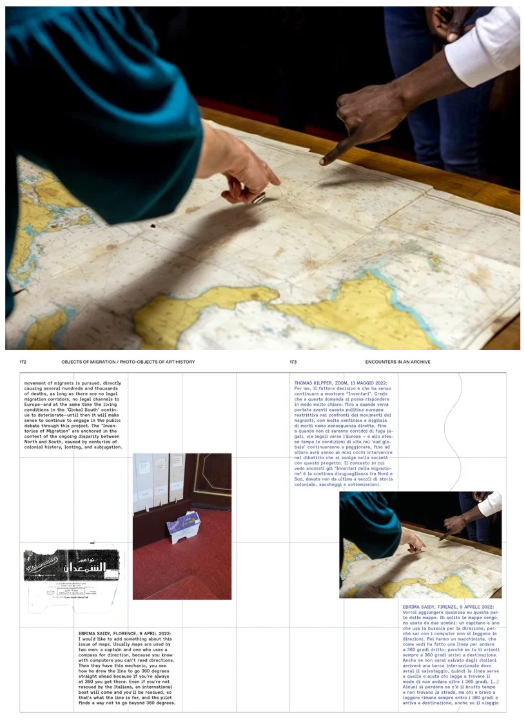

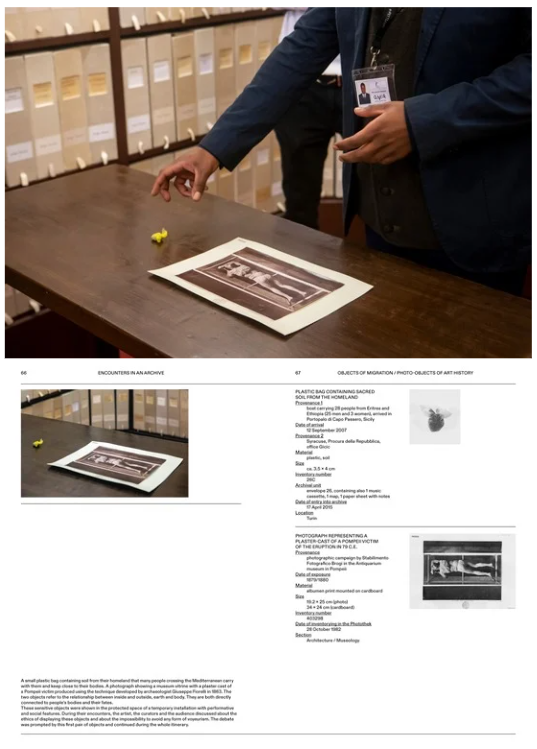

We need more research in this kind of collection – research at many levels. It can be by young students, by the curators and archivists themselves or by external researchers. Here I would rather like to mention a different kind of project that we did recently with an Italian artist, Massimo Ricciardo, called ‘Encounters in an Archive: Objects of Migration / Photo Objects of Art History’.

Ricciardo has collected objects of migrant people in Sicily and Lampedusa. He started the project with an installation within the Photothek, putting objects from ‘his’ archive in our spaces because we were having a conference about photography and migration.

Then we started a dialogue and in the end we installed pairs of objects. One object of migration with one photo object from the Photothek, which were in dialogue for many reasons, by contrast or by familiarity and so on. We discovered that we have many common topics and could explore different interpretation levels giving the same importance to each object in the pair. I don’t want to compare the importance of objects of migrant people whose destiny is not known to us – objects that have to do literally with life and death – whereas our photographs are something else…in that case I have to give up!

The dialogue and the setting within the archive, with the shelves and the boxes and the order and structure that incorporates the power of the archive – the effect was so powerful because it enhanced the strength and energy of these objects. It was a way to open the archive to contemporaneity, and the project ended up in a book (Caraffa and Goldhahn (eds), 2023) in which we continued the conversations with a community of cultural mediators with a migration background who are active here in Florence. So at this small scale we were able to open the archive for something that is much bigger than photographs, so much bigger than art history, much bigger than archives.

It was a good project for us and a good moment for the people who reactivated their histories and the objects through their conversations, people sometimes with the same experience of migration, they gave a new life to these objects. It was a powerful encounter.

Elizabeth: I entirely agree with Costanza that research is vital to take archives forward. This is getting squeezed out of museum funding. But research doesn’t just enhance parts of the collection, as Costanza just described.

It sensitises curatorial thinking to what is possible. It inspires archival visitors too, and I’ve always felt that my best theoretical ideas have come to me sitting in the archive, looking at photographs, doing research. It’s a question of how we can use those archives to inspire further research and bring them into the centre of people’s thinking.

Costanza: I would add, Elizabeth, that you are looking at photographs in an archive doing research, but you have the experience of the archive. This is something that we not only practice in our professions, but we can also transmit going beyond this separation between research done by researchers and the

stupid and boring work of the archive. You understand things differently if you know the practices of the archive as a researcher as well as an archivist.

Concluding thoughts

Ruth: Well thank you very much – do you think we have come to a conclusion? In this conversation we have explored the thinking that goes into working with large photographic collections and archives. We have how photographic collections are not static but are constantly being made and remade. Such collections require an adaptive approach to collections management, which recognises seriality and contextual networks, and documentation approaches that build relational models between archival and museum collections management practices (Jones, 2018).

Finally, this conversation looks towards more collaborative approaches to collections access in photographic collections, through which users can map their own personal journeys through vast collections, and museums and archives can build greater networks within communities to shape digitisation priorities. It is a conversation which is sure to be ongoing.