Keynote: The science that Versailles forgot

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/252306

Abstract

This article is from the keynote presented by Professor Colin Jones at the Versailles: Science and Splendour conference on 13 December 2024. The conference discussed the interconnected history of the eighteenth-century French court and medical and scientific innovations that were fuelled by the resources – both economic and intellectual – available through Versailles before the French Revolution. The conference was concurrent with the opening of the Science Museum’s Versailles: Science and Splendour exhibition, which was open from 13 December 2024 to 21 April 2025. It features a large collection of scientific and medical equipment from Versailles, including a watch designed for Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI’s rhinoceros, and Cassini’s map of the moon. Emphasising and teasing apart the relationship between power and scientific discovery, the conference gathered an international set of academics and was presented in both French and English.

Keywords

Abbé Nollet, exhibitions, Exhibits, French history, French Revolution, medicine, scientific apparatus, Versailles

Keynote

Like Humpty Dumpty, the palace of Versailles suffered a great fall. In 1789, it had been the royal residence of the Bourbon dynasty for more than a century, the seat of government, the symbolic heart of the French nation, and it was widely regarded as one of the most significant and influential cultural sites in the modern world. It had been custom-made for the French Bourbon dynasty at the end of the seventeenth century by Louis XIV (ruled 1643–1715), and his successors Louis XV (1715–74) and Louis XVI (1774–92) had continued his passion for it. But in 1789 the French Revolution struck like lightning, and the monarchy was forcibly removed from the palace. This dynastic abandonment triggered decades of distaste for the values the site had seemed to embody, and the woeful neglect of its buildings.

In the late nineteenth century, visionary attempts started to be made to recreate the lost Versailles of the pre-Revolutionary era. For better or worse, belated efforts to put Versailles, like Humpty Dumpty, together again wholly neglected the science that had been conducted there. It took the landmark exhibition, Science and Curiosity at the Court of Versailles, held in Versailles itself in 2011–12 to draw attention to this glaring oversight. Now, the Science Museum builds on that achievement to provide anglophone audiences with insight into the much-neglected scientific aspect of France’s greatest world heritage site. It allows us to access the Versailles science that France forgot.

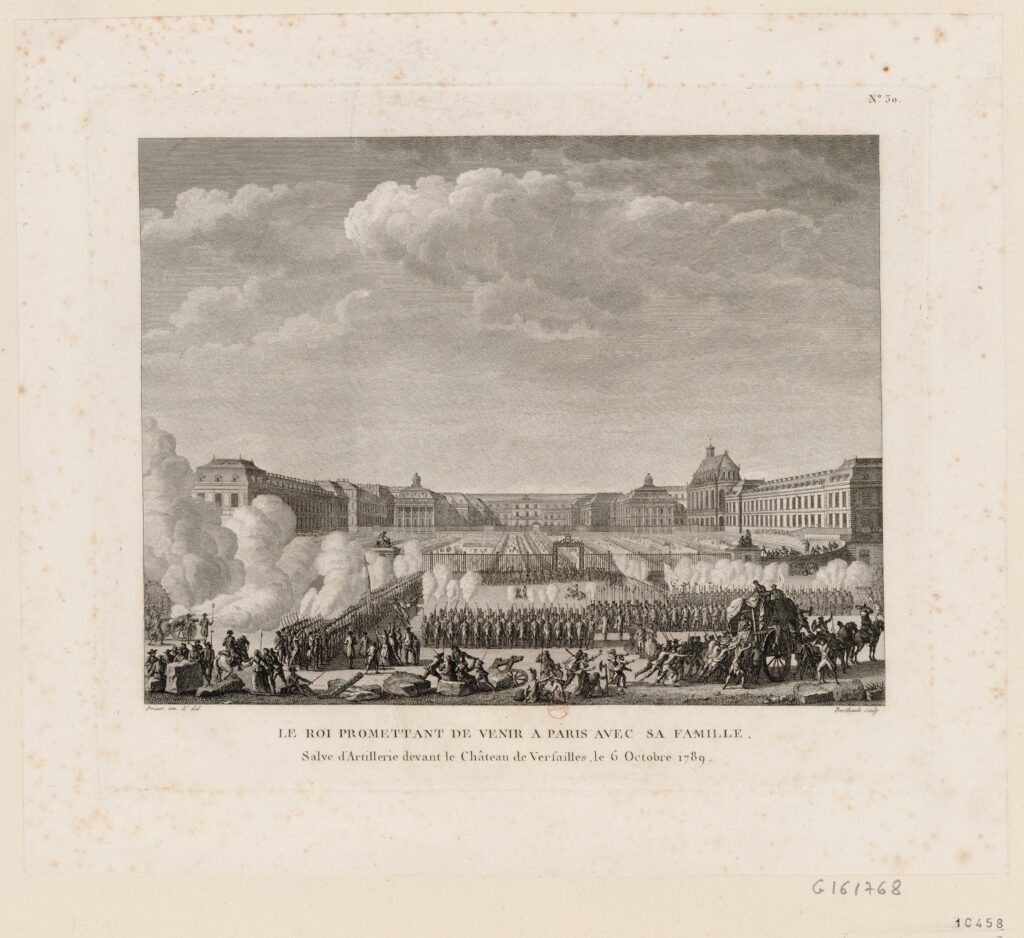

This extraordinary century-long act of national amnesia owed much to hostility in post-1789 political culture towards all that Versailles appeared to have stood for. From its outset, the French Revolution seemed committed to consigning Versailles to the dustbin of history, even though, oddly, it was in Versailles that the Revolution had started. May 5, 1789, saw the opening ceremony of the ancient national parliament, the Estates General, called by King Louis XVI to find a solution to the French state’s impending bankruptcy. It was held in the church of Saint Louis in the city, while the meetings of the Estates also took place outside palace precincts, in the Hôtel des Menus Plaisirs, the royal organisation responsible for overseeing royal ceremonial events. And it was in a nearby sporting venue in the city that on 20 June 1789 commoner delegates to the Estates swore the famous Tennis Court Oath, when, as the National Assembly (as they now called themselves), they swore not to disperse until France had a new constitution. They forced the king to accede to their wishes in the summer crisis of 1789, which saw the storming of the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789. The work of creating the new constitution under guidelines provided by the historic Declaration of the Rights of Man of 26 August got under way.

Louis was unhappy with the way the Revolution started to run, yet if he thought that the palace that he cherished would remain aloof from the political transformations under way, he was much mistaken. In early October 1789, royal troops proved unable to repel crowds of Parisians who invaded the palace precincts – at one point making queen Marie Antoinette run for her life through palace corridors – and forced the monarch to remove himself, his family and indeed the National Assembly from Versailles to Paris.

“Try to save my poor Versailles for me,” Louis entreated the Comte de La Tour, governor of the Versailles palace, as he stepped into his carriage, never to return (de La Tour du Pin, i. 232). With the overthrow of the monarchy on 10 August 1792, and the declaration of a republic on 21 September, he was forced to reside in the Tuileries palace at the heart of the French capital under close Parisian surveillance.

The new Republic had no time for Versailles – ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’ was not the Versailles watchword. The new government was energetic only in its iconoclasm; fleurs-de-lys, royal and feudal armorial bearings and the like were systematically removed from the exterior and from the internal rooms of the palace. Many revolutionaries were quite happy to allow Versailles as a whole to go to rack and ruin through lack of maintenance. Calls for the whole complex to be razed to the ground and turned into ploughland were not heeded, but this was partly because such an enterprise would have been just too costly. The palace seemed to represent everything French revolutionaries were most against: they held that before 1789, king and court had lived parasitically on the French nation, and Versailles had served the vanity of a single man who claimed to rule with absolute power and by divine right.[1] The state’s financial crisis of 1789 was laid at Versailles’ door too (unjustly, in fact, since debts accrued in fighting dynastic wars were the main problem, not lavish court expenditure).

On 5 May 1794, the National Assembly passed a law that effectively nationalised Versailles, in a decree that ‘conserved and maintained [it] at the Republic’s expense for the enjoyment of the people and to create institutions useful for agriculture and the arts’ (Jones, pp 117–118). Yet no real effort was shown to put such plans into effect and indeed the 1790s saw a massive clear-out of the palace’s splendid material culture. In a first triage, objects of value or judged of historical importance were shifted to other national institutions, many newly created and all based in Paris. Scientific instruments and machines were directed into the Arts et Métiers school and conservatory as part of a more general relocation exercise. Artworks went to the Louvre palace, now repurposed as a museum; precious books and manuscripts went to the national (rather than royal) library and archives; and musical instruments to the Paris Opera. The few exotic animals remaining in the Versailles menagerie were rehoused in the Jardin des Plantes (formerly Jardin du Roi) in the capital. The group included the ageing Indian rhinoceros imported in 1770. Dying almost immediately on transfer for reasons unknown, the animal was stuffed in 1793. This triumph of taxidermy has been housed ever since in the Museum of Natural History (though it has been allowed out, to be one of the stars of the Science Museum’s exhibition). These official transfers were only the tip of a larger process of disposal and reappropriation. There was a certain amount of looting by the local population and a huge amount of the material culture and furnishings of the palace were auctioned off – everything from high-level furniture down to mattresses, candlesticks and kitchen utensils. The result was the reduction of Versailles to a bare shell of its former being – ‘a body without a soul’ as the Russian visitor Nicolay Karamzin noted sadly.[2]

Intermittent efforts across the nineteenth century to find Versailles a post-Bourbon vocation (notably King Louis-Philippe’s creation of a museum of national history) failed to stop it becoming, as the novelist Stendhal noted, ‘a sad place [where] one yawns before dying of boredom’.[3] At the end of the century, Marcel Proust largely concurred: the whole site had become merely ‘a great name, sweet and tarnished, royal cemetery of leafy glades, vast lakes and marbles’ (Proust, p 176).

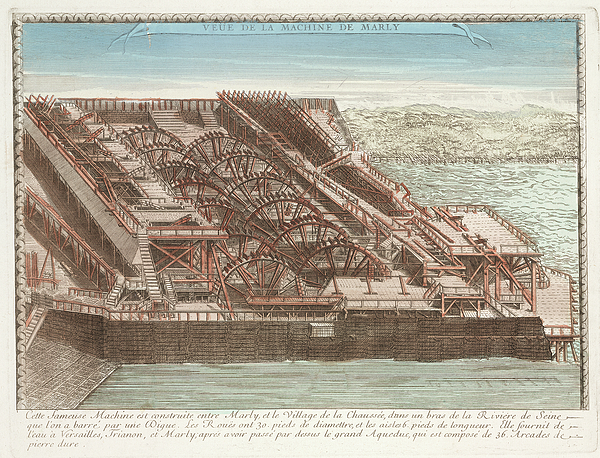

(Above, Figure 6: D W Pendery, computer model showing working animation of the Marly Machine)

Of all the activities that had gone on in Versailles prior to 1789, it was science that was the biggest loser in this story of forgetting. The late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century efforts that were finally made to live up to the nationalisation of the site in 1794, and to create Versailles as a site of national memory with a recreation of its former splendour, focused almost exclusively on the beaux arts rather than sciences. In fact, science was in Versailles’ DNA. It had played a considerable part in making Versailles even possible. When Louis XIV moved his court and government here in 1682, the ornate garden fountains, which remain to this day one of the site’s most renowned features, exemplified the priority the ruler gave to all-surpassing ostentation. Yet water for the fountains – and for the kitchens and the gardens – was in short supply on the wind-swept plain on which the palace was constructed, and a number of water supply schemes had to be created, most notably the so-called Marly Machine, which brought water from the Seine at a point some 150 metres or more below the palace. It was probably the most complex scheme of hydraulic engineering in the whole of the seventeenth century. The scientific feat, however, was eclipsed by the majesty of the fountains it served.

A good deal of the science that went on in Versailles was like this. The appropriations and transfers of the Revolutionary decade denuded the site of material objects of science, but in fact science had been relatively invisible for visitors even before 1789. Visitors had swarmed through the Menagerie but had had little idea that the exotic animals they saw there were subsequently dissected, broadening the understanding of comparative anatomy.

The visitors were probably only dimly aware of the extent of botanical work undertaken in the palace’s gardens; nor would most know of the serious work on plant acclimatisation – the growing of melons, peaches and pears, for example, as well as coffee and pineapples – taking place in the royal kitchen garden (the Potager du Roi), that also attested to France’s broadening commercial and colonial horizons. Some parts of the Versailles palace and estate were anyway off-limits for visitors: outsiders were not permitted entry to the famously heroic surgical operation on Louis XIV for his teeth in 1685 which cauterised his palate with a red hot iron, nor did they witness the surgery on a life-threatening anal fistula the following year nor, later, the experimentation with smallpox inoculation on members of the royal family in the 1770s.

The cornerstone of the scientific enterprises of Louis XIV and his successors was the Academy of Sciences, established in 1666 and bolstered in the early years by Louis XIV’s famous minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Pure science certainly had its place within the Academy, but applied science was particularly favoured for its potential to help build up state power and allow territorial expansion in Europe and the wider world. Advances in astronomy were made, for example, with their use in cartography, geography and navigation very much in mind. Astronomy remained something of a Bourbon specialty in fact, impassioning all the three Louis. It was strongly present in the rounded scientific education that as children both Louis XV and Louis XVI received. They also cultivated their own scientific tastes. Louis XV, for example, loved scientific instruments, surgery (he created the Academy of Surgery in 1731) and botany. He had a certain flair for mechanics and architecture too and had a ‘flying chair’ installed to convey one of his mistresses to his bedroom from lower floors, a precursor of the modern lift. For his part, Louis XVI had a set of customised laboratories and scientific cabinets in his private apartments (well off the track for courtiers as much as visitors) and there he indulged his passions for physics, chemistry and mechanics (notably lock-smithing and clock-making). In his private gardens at the Trianon he conducted botanical and agronomic research with the hope of improving food supply for his subjects. (His delight was very evident when in 1786 the pharmacist Parmentier presented him with the potato, and had it served up for the king’s supper.)

The establishment and maintenance of the Academy of Sciences showed the Bourbon dynasty’s commitment to large-scale projects well beyond the financial means of private individuals. In 1667, Louis XIV commissioned Cassini to erect and manage a royal observatory on the southern edge of Paris. It proved the basis of a long-term commitment to astronomy and cartography in which four generations of the Cassini dynasty participated.

The naval expedition of discovery in the Pacific to be led by La Pérouse was commissioned by Louis XVI in 1785 in the wake of Bougainville and Captain Cook and was a further example of major state funding. Louis’s passion for science, geography and naval affairs was also in evidence in his plans for the fortification of the port of Cherbourg, with the beginnings of the artificial bay that would in time become one of the largest in the world.

If the role of science at Versailles was and has since been underestimated, this was not only because it was not highly visible. A further reason is that at the other extreme, the royal court was receptive to spectacular scientific demonstrations that did not seem to have obvious scientific justification. Abbé Nollet’s jump-inducing electric shock was delivered in 1746 in the Versailles Hall of Mirrors to 140 royal guards holding hands in a circle while linked to a Leyden jar. It counted more as entertainment than science to most courtiers. The Abbé’s experiments with air pumps became widely enough known to be satirised by court embroiderer Charles-Germain de Saint-Aubin.

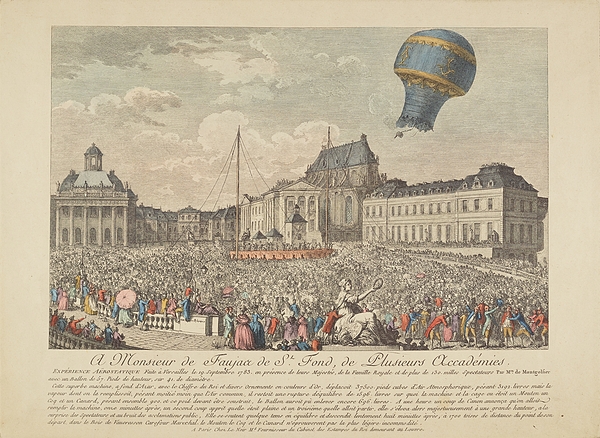

In 1783, an audience of over 100,000 people cheered brothers Joseph and Étienne Montgolfier as their hot-air balloon rose in the air from a palace courtyard bearing a sheep, a duck and a cockerel. The experiment’s contribution to aeronautics was largely overlooked.

Furthermore, outright charlatanism was sometimes presented as science, as with Mesmer’s orgasm-inducing experiments with animal magnetism in the 1780s.[4] Spectacular pseudo-science at Versailles sometimes gave science a bad name.

Even so, the manifold ways in which science persistently manifested itself in Versailles’s life makes the amnesia that long surrounded it seem all the more unjustified. The Bourbon monarchy was highly encouraging to scientists, supported research projects, financed scientific careers, and legitimated scientific endeavours in a striking way. Kings also opened up emerging sectors of government concern to scientific enquiry, including health, marine engineering and agronomy, while science also helped give the monarchy a more imposing global presence in terms of trade and expansion.

Versailles was a cultural dynamo and a blueprint for monarchical government that many eighteenth-century rulers revered and sought to imitate. A case could also be made that it worked as a kind of science hub drawing in scientific knowledge and diffusing it across the globe – but with one reservation, namely, that it operated in all matters scientific in close symbiosis with the city of Paris, which lay only a handful of miles down the road from the palace.

Versailles science derived an enormous amount of its drive and dynamism from its proximity to the French capital, with which it was in happy synergy. Much Versailles science took place either in, or in association with, the French capital. Royal financial support was insufficient for scientists to make their livings out in Versailles: most scientists who were engaged in Versailles science thus lived in Paris and came out to the court when they were needed (and more often than not they would lodge in the city of Versailles rather than at the palace). The Academy of Sciences, to take a striking example, was housed at the royal palace of the Louvre, even if it did take orders from a minister lodged in Versailles. Whatever their intellectual éclat, moreover, savants always took second place at Versailles to courtiers; in Paris, in contrast, some of those very courtiers would come happily to sit at the feet of Parisian intellectuals, attend salons and frequent the cultural, scientific and leisured institutions that had made Paris the capital of the European Enlightenment.

The scientific symbiosis that Paris and Versailles achieved from the reign of Louis XIV was impressive. Even so, there were telling signs as the eighteenth century wore on that the relationship was waning. Over the century, the royal court was becoming more not less exclusivist in its admissions policies. Lavoisier, the greatest scientist of the late eighteenth century, was summoned to Versailles a few times in his life, but this was for business in his other profession as a tax farmer. The thought that Denis Diderot, the impresario who edited the great Encyclopédie, might ever be received at court was laughable: he was the son of a master cutler. The father of mathematician Mme Du Châtelet held a lofty court position at Versailles, and she married a high-ranking marquis; but she spent her adult life as companion of the master philosophe Voltaire, son of a Parisian notary.[5] These eminent scientific figures were fish out of water in the Versailles court but very much in their element in Enlightenment Paris.

The visit to France in 1777 of Queen Marie-Antoinette’s brother, the future Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, was revealing of the change now taking place. He disrespected the court by choosing to sleep in the city of Versailles rather than the palace and spent most of his time visiting Paris and its scientific and cultural institutions – the Academy of Sciences and the Jardin du Roi, but also the Savonnerie carpet manufactory, the royal glassworks, the School of Surgery, the Invalides, Hôtel-Dieu hospital, the École Militaire and so on. Paris was where cutting-edge science took place.

As 1789 approached, intellectual, cultural and scientific figures felt less in thrall to Versailles than their predecessors. Paris had lost any sense of inferiority it might have had towards the royal palace. Indeed, the Parisian public sphere was increasingly viewed as a kind of counter-culture, a counter-Versailles in fact, critical of Bourbon monarchy and all its works. The palace, the journalist Louis- Sébastien Mercier opined, was like ‘a satellite revolving around the whirlwind’ that was Paris (Mercier, iv. 278). The myth of Versailles as the unserious (and unscientific) home of trivial courtiers and lavish surroundings was being created long before 1789.

This shift in the balance of scientific power between Versailles and Paris makes the Revolution’s savage break easier to understand and indeed to accommodate than one might have thought. Despite a hiatus for part of the 1790s, French science continued to progress by leaps and bounds, even with no Versailles to fall back on. This made it easy for France to forget the science that was an integral part of the old Versailles.