‘As snug as a bug in a rug’: post-war housing, homes and coal fires

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/180902

Abstract

This article examines the layers of meaning and value attached to the image of the open coal fireside in the years immediately following the end of the Second World War. Although the open fire has a much longer economic, social and cultural history, it is argued here that after 1945 it took on new, emergent meanings that tapped into pressing contemporary debates concerning the nature of the modern British nation, the home and the family. Whilst writers often evoked the experience of the open fire as a timeless comfort, addressing basic human needs, the fireside of post-war British journalism and illustration was a very modern thing indeed, able to express specific debates arising from the requirements of reconstruction and modernisation. The almost folkloric associations of the open fire made it harder in the 1950s to legislate against domestic smoke than it was to regulate industrial pollution. Vested interests drew on the powerful rhetoric of the coal fire to combat the smoke pollution reports of the early 1950s and the growing inevitability of legislation. The coal fire was part of a post-war chain of being that started with the domestic hearth and progressed to the nuclear family, the self-contained home, the nation, and ultimately to the Commonwealth.

Keywords

advertising, coal fire, commonwealth, family, heating, homes, journalism, nation, post-war Britain

‘As snug as a bug in a rug’: post-war housing, homes and coal fires

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/180902/009Images of homes and heating pervade British culture after the end of the Second World War. They are present in novels, films, advertising, journalism and painting; in both the background and the foreground of representation. These images always amount to something more than the sum of their parts; they are never just about the forms of domestic space but speak of ideas that are deeper and more defining. The appearance of the open fire contained within the protective frame of the fireplace seems to speak to timeless values of comfort and repose, or to address an undefinable human need. In his Psychoanalysis of Fire (first published in 1938), the French philosopher Gaston Bachelard described the experience of reverie before an open fire as an essential human comfort that lies beyond historical determination (Bachelard, 1964). While such a claim appears to conform to common sense and shared experience, it also demonstrates the power of this particular mythology. Roland Barthes’s work on mythology offers a useful framework for an understanding of the ways in which representations of the fireside have been circulated and consumed. For Barthes, the most important effect of myth is the transformation of history into nature; the way in which it suppresses historical conditions of existence in its production of meaning as timeless and inevitable. In this way, he describes myth as ‘the foundation of a collective morality’ (Barthes, 1972, p 59). To be sure, the fireside has a long and deep history, but its longevity is part of its mythic form. Whilst it bears the symbolism of ancient humanity it is also able to address very modern concerns indeed.

This article examines the specific contemporary meanings of the post-war British fireside and of the coal fire in particular. Drawing on residual ideologies, it also expressed new, powerful meanings that specifically addressed the concerns of the post-war nation. Whilst these issues were defined in official discourses and fought over by commercial interests, it was in cultural life, and specifically through the visual forms of advertising and illustration that the myth of the post-war open fireside was most effectively popularised and disseminated. In the decade or so following the end of the war, domestic heating and, in particular, the look and feel of the open coal fire, was an active agent in debates concerning the reconstruction of the nation, the nature of British modernity and the future of the family.

Housing was the first great problem for post-war Britain.[1] Its significance went far beyond the provision of dwellings, however. War had shattered families, physically, emotionally and psychologically and the home was necessarily the foundation of post-war social reconstruction and the restoration of family life; home would repair the damage of war. As the locus of economic and political power, the foundation of social reconstruction and the bedrock of emotional and psychic well-being, the home permeated all aspects of public and private life in the post-war period. It defined the aspirations of peacetime Britain and was the distinctive discourse of the period. Although housing was about material realities, it also existed through more abstract and intangible forms, in cultural expression and individual longing; it created the tones of post-war Britain. Whilst political parties struggled over the numbers of homes built, the home was not about statistics, it was about the qualitative life of the period and its deep expression, what Raymond Williams has called its ‘structure of feeling’ (Williams, 1958, 1961, 1977).

In the years immediately following the war social workers and psychiatrists were agreed that British society was in a transitional stage and that the housing shortage was having a destructive effect on the lives of a generation. In a survey of two hundred soldiers and their wives, carried out between 1943 and 1946, Eliot Slater and Moya Woodside examined attitudes to marriage and concluded that the desire for a home was the most common reason for marriage and was of key importance to individual happiness. They found a huge disparity, however, between the fantasies of home and the material realities of post-war accommodation. Many couples were living with relations, or were renting rooms and flats in houses:

We found attics, top floors and basements; rooms over shops, pubs and off-licenses; bomb-damaged houses still unrepaired or partly repaired; unpainted cracking walls and ceilings; damp, draughts, and black-out arrangements permanently in position. The families who live in these homes had inadequate storage…inadequate washing facilities… Many had no furniture of their own… Others had to make do with bare half-furnished rooms, decked out with the few pathetic bits and pieces they had been able to collect.

These were the forms of post-war domestic life; while exhibitions created furnished room sets and manuals set out the ‘rules’ for good interior design, many were living in surroundings that belonged more to wartime than to peace and that were more suited to life in a Victorian city than the planned towns of the post-war world. With little privacy and shared facilities, multi-occupancy houses were the reality for many who were ‘setting up home’, a situation that Slater and Woodside described as the ‘…tragedy of our era’ (Slater and Woodside, 1951, pp 217, 125).

Plans for housing that started out as radical visions of a new, modern society were frequently compromised by squeezed resources and political realities; the need for accommodation was so severe that large scale ambitions had to take a back seat to the basic provision of shelter for families. There remained a strong sense, however, that housing was not enough to restore society and did not necessarily create the homes and families that had been torn apart by the war and that were at the heart of social reconstruction. Whereas housing suggested a kind of anonymous mass, home was particular and individualised; it was the object of emotional and psychic investment and was associated with memory and with the past as much as with the modern and the new (Roberts, 1989, p 3).

The object that seemed to embody the emotional affects of home and its restorative capacities was the open coal fire. In spite of its inconveniences, for many the mythology of the flames of the coal fire was a lived experience, representing all the accumulated meanings of home and family. Whilst bearing an almost primordial symbolism, they were a source of comfort that still claimed a place in modern, post-war society. Although these associations were present in earlier periods, they had been intensified during the war years, when the domestic hearth symbolised not only the individual family home but the home fires of the nation. In 1943 and in anticipation of a housing shortage when the war ended, Mass Observation published a survey of people’s attitudes to home for the Advertising Service Guild (Enquiry, 1943).[2] Chapter sixteen was devoted to the subject of ‘Warmth’. Drawing on a random sample taken in May 1942, the survey stated that 78 per cent of people used coal for their living rooms, compared to only 15 per cent who used gas and three per cent who used oil. Moreover, asked ‘what type of heating they would like if they could choose’, 73 per cent said they would prefer an open coal fire. The reasons for this choice went beyond the provision of warmth, relating to what the report referred to as ‘Coal Feelings’. The coal fire was ‘cheerful’, ‘homely’, ‘comforting’ and looked nice; it had emotional and aesthetic qualities, ‘intangible virtues’ that were lacking in gas and electric fires (Enquiry, 1943, pp 136–7).

One of the great advocates of the national coal fire was George Orwell. In his 1941 essay, ‘England Your England’, he evoked the embattled nation in terms of its essential and everyday values, ‘…the pub, the football match, the back garden, the fireside and the “nice cup of tea”’ (http://orwell.ru/library/essays/lion/english/e_eye). These were images and ideas that symbolised an authentic working-class culture but which also superseded class and cohered a nation. Shortly after the end of the war Orwell went further. Saturday 8 December 1945 was a bitter winter’s day. The forecast, published on the front page of the Evening Standard, was ‘very cold: keen frost: local snow’. In a column on the inside pages that day Orwell addressed the question of homes and heating in post-war Britain. As the nation moved from hurriedly constructed prefab houses to the provision of permanent homes, Orwell argued that every house or flat should have at least one open fire:

For a room that is to be lived in, only a coal fire will do… This evening, while I write, the same pattern is being reproduced in hundreds of thousands of British homes. To one side of the fireplace sits Dad, reading the evening paper. To the other side sits Mum, doing her knitting. On the hearthrug sit the children, playing snakes and ladders. Up against the fender, roasting himself, lies the dog. It is a comely pattern, a good background to one’s memories, and the survival of the family as an institution may be more dependent on it than we realise.

(Orwell, 1945), p 6

Hyperbole, perhaps, but Orwell draws on a powerful ideology connecting the traditional family home and the coal fire. Like mother and father, the fireplace should have a capital letter, for its place in constructing family life is equally pivotal. And Orwell suggested one further significance of the coal fire, it warmed the imagination as well as the body:

Then there is the fascination, inexhaustible to a child, of the fire itself. A fire is never the same for two minutes together, you can look into the red heart of the coals and see caverns or faces or salamanders, according to your imagination… A gas or electric fire, or even an anthracite stove, is a dreary thing by comparison.

The open coal fire thus had ‘an aesthetic appeal’ and even the restricted heat it produced had a positive impact on family life, enforcing ‘sociability’ as parents and children huddled within the parabola of its warmth. It was an enduring myth. In 1957, in The Uses of Literacy, Richard Hoggart mourned the loss of authentic, working-class culture and community, symbolised by the family hearth: ‘Warmth, to be “as snug as a bug in a rug”, is of the first importance…a fire is shared and seen’ (Hoggart, 1958, p 22).

In spite of the accumulated symbolism of the coal fire there was growing acknowledgement in the post-war period that burning coal from domestic fireplaces was polluting the urban environment. Coal was difficult to store in bulk, it was awkward and dirty and with post-war shortages it was not necessarily a cheap option. Increasingly, the open fire was being used in combination with other forms of heating such as gas or electric fires. The coal fire might possess residual sentimental values, but it was not the fuel for a modern, clean, stream-lined post-war Britain.

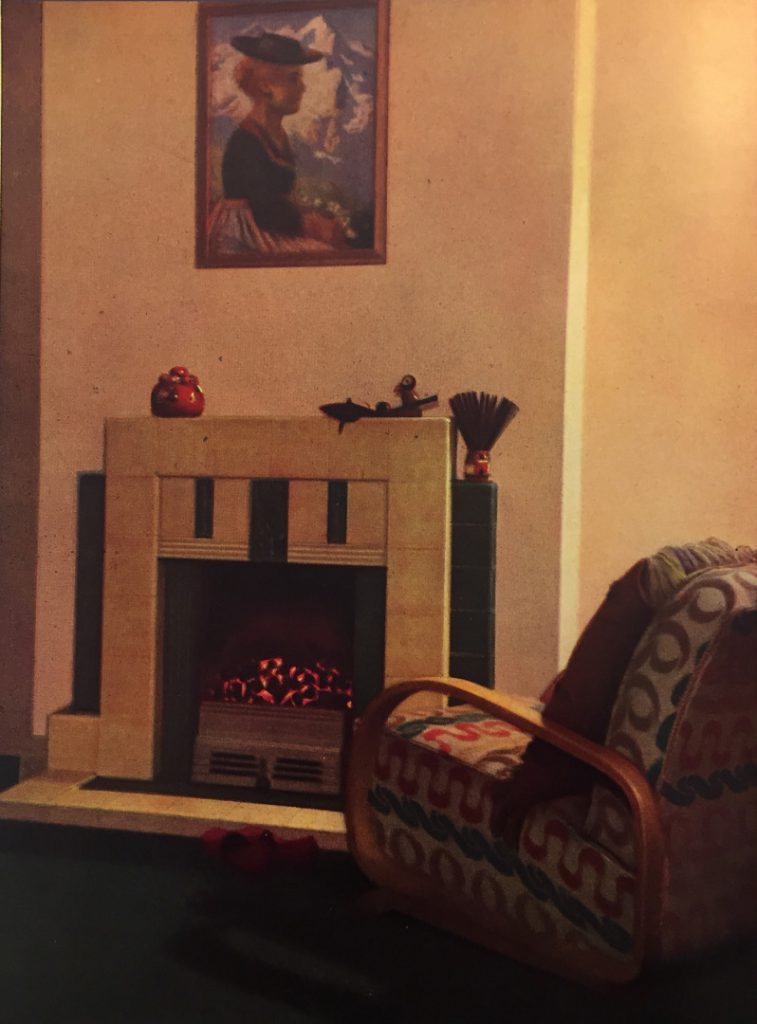

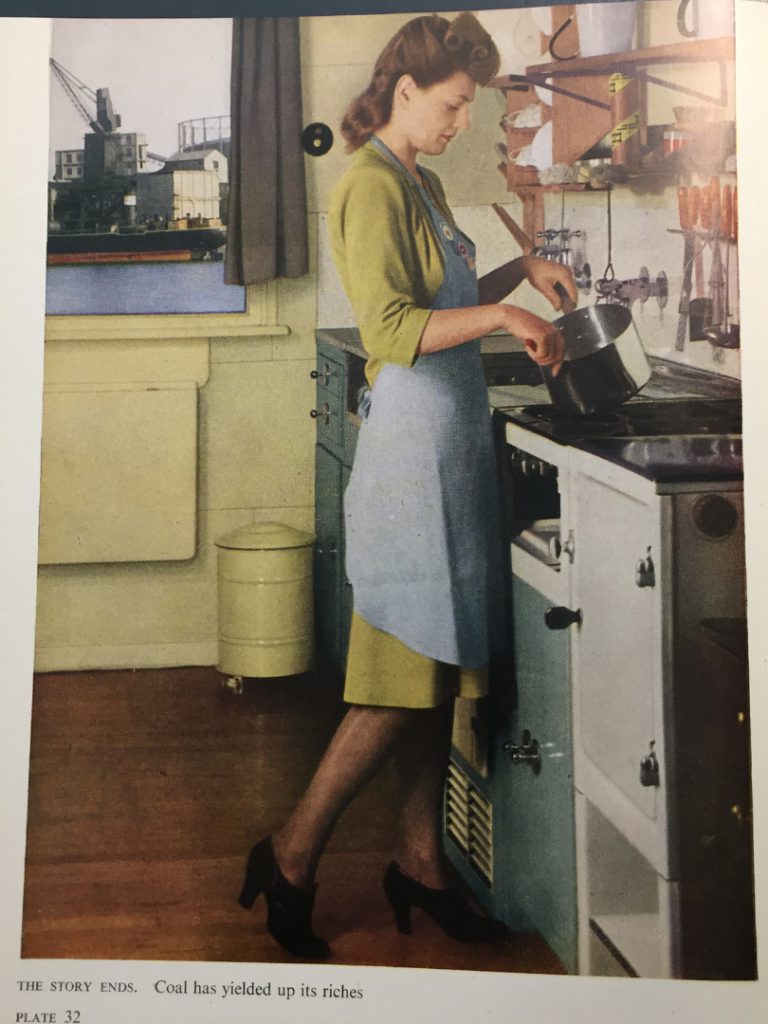

By the late-1940s a number of new council developments had been completed, which offered more space, better facilities and different forms of heating. In 1947 the Scottish writer Compton Mackenzie published The Vital Flame, a paean to gas, commissioned by the British Gas Council. Illustrated with 42 colour photographs, it celebrates the industrial, agricultural and domestic uses of gas power. Mackenzie describes a visit to a municipal block of flats, Kensal House in London, which provides ‘smokeless homes’ and is visited by architects and planners from all over the world (Mackenzie, 1947, p 34; see also plates 8, 28 and 32). Individual flats have gas cookers and water heaters and a ‘gas-ignited coke fire’ provides a cosy, but smokeless, fireside glow. Colour plates show the uniform, geometric lines of the exterior, as well as interiors such as a living room with slippers warming by the fireside (see Figure 1). The final plate is captioned: ‘The Story Ends. Coal has yielded up its riches’ and shows a woman cooking with gas and colour coordinated with her modern fitted kitchen, with a view of a gas power station through a window behind her (see Figure 2). The wealth that coal yields is gas.

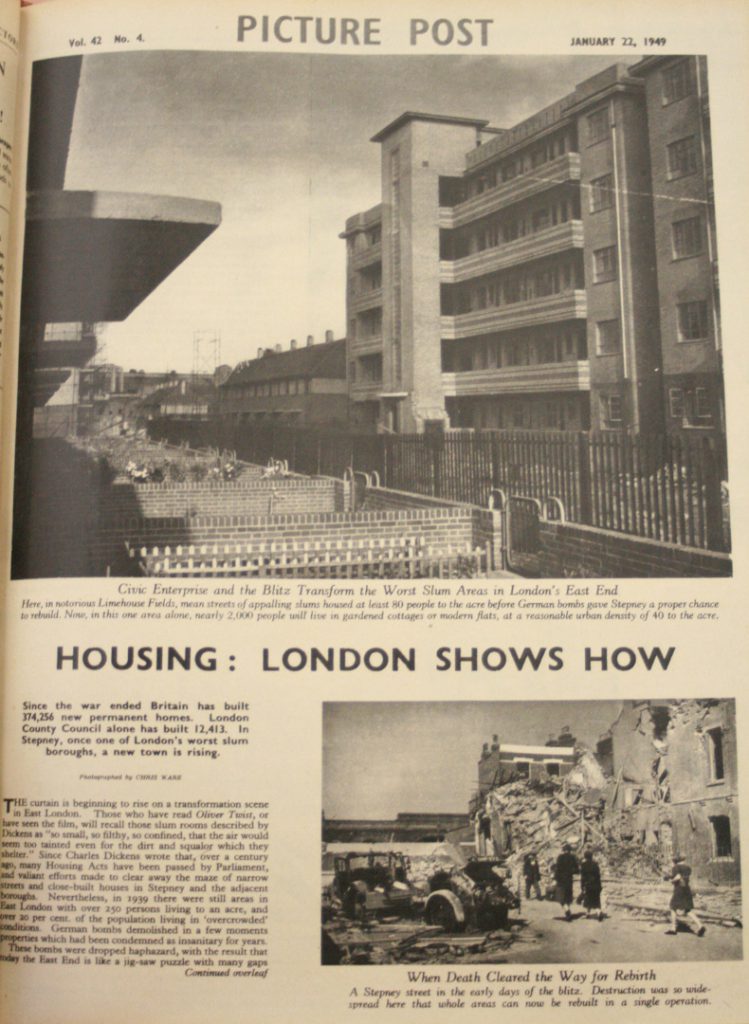

In the years immediately following the war, it was evident that the open coal fire was incapable of providing these amenities and could not remain the fuel of modern housing. Bombing had continued the destruction of Britain’s old housing stock and it was time to do away with Victorian living conditions. In January 1949 the illustrated weekly magazine Picture Post, which reported regularly on the progress of reconstruction and the condition of British cities in the decade following the end of the war, carried an article titled ‘Housing: London Shows How’, about the new housing developments in Stepney in the East End (see Figure 3). Comparing the old housing in the area to scenes from Oliver Twist, it assured its readers: ‘The flats of 1949 are not the ugly tenements of Victorian days. They will be surrounded by playgrounds and railed-in gardens’ (Townroe, 1949, p 33). It lists the facilities offered inside the accommodation including: a boiler in the kitchen; a sun balcony; and living-rooms with open fires (Townroe, 1949, p 8). This was the shape of the future, with flats and communities that would not only address the chronic housing problems of the nineteenth century, but would also create functional, modern living and, most importantly, homes that would restore and renew.

There is a fascinating oscillation in representations of home in these years between notions of the modern, the new, a fresh start and nostalgia and the persistence of the past, which is encapsulated in debates about the place of the coal fire in the modern home. Although the open hearth represented the heart and soul of the family home, a place of reverie and memory, it was also dirty and inefficient and was as responsible for the polluted air of Britain as smoke from industrial chimneys. One of the foremost domestic design questions, therefore, was how to resolve these competing objectives, how to provide the cosy atmosphere of the coal fire economically and without pollution. Engineering companies advertised adapted grates and boilers that would heat homes cleanly and efficiently, whilst retaining an open fire.[3] Here was a modern fire in a modern home; still using coal or coke but heating radiators and supplying hot water at the same time as providing a centrepiece for an uncluttered and comfortable living-room (see Figure 4; National Smoke Abatement Society, 1951, p 44). Ornaments on the mantelpiece, but not too many; coal in the fire ‘that warms three other rooms’.

Domestic heating had become one of the key debates of social reconstruction. Smoke pollution and fuel consumption were the subjects of a series of campaigning articles that were published in Picture Post in the early 1950s. ‘We are throwing away our birthright in a pall of smoke’, it stated (Stobbs, January 1952, pp 30–31). Eighty per cent of coal used in 1951 was wasted; it was time to abandon the open fire and move to the closed stove: ‘New types of stoves and fires that give improved warmth and efficiency but without sacrificing cheerfulness’ (Stobbs, January 1952, p 15; see also Stobbs, March 1952, pp 15–17). To fuel reformers the arguments seemed clear cut; others, however, remained unconvinced. In January 1952 Picture Post quoted Mrs Charlton, the wife of an estate agent, who insisted: ‘I like to see the fire. Even if it does cost us more to keep our old fire going, we’ll still stick to it. It’s more cheerful, more homely. This [closed stove] looks so cold’ [original emphasis] (Stobbs, January 1952, p 14).

Following the Great Fog of December 1952, during which London was plunged into five days of thick smog and mortality rates soared, the arguments against domestic coal use became increasingly unassailable. There was a new urgency and public awareness to ongoing debates concerning air pollution and, following pressure from MPs, a Committee of Inquiry was set up under Sir Hugh Beaver, which published its final report in 1954 (see Nead, 2017, chapter one). Clean heating was a priority for modern homes and designers reworked the image of the open domestic fire so that it was compatible with the new furniture lines, the abstract forms and restrained patterns of post-war progressive living. ‘Let’s Keep the Home Fires Burning Without Wasting Heat and Fuel’, demanded a Picture Post journalist in 1955. ‘Keep the home fires burning’; it was a phrase that evoked the spirit of the nation in wartime but this was a different post-war world. The new fires and stoves ‘…cut fuel bills, make rooms and houses warmer, and – horrors! – they look entirely different’ [original emphasis] (Stobbs, 1955, pp 36, 37).

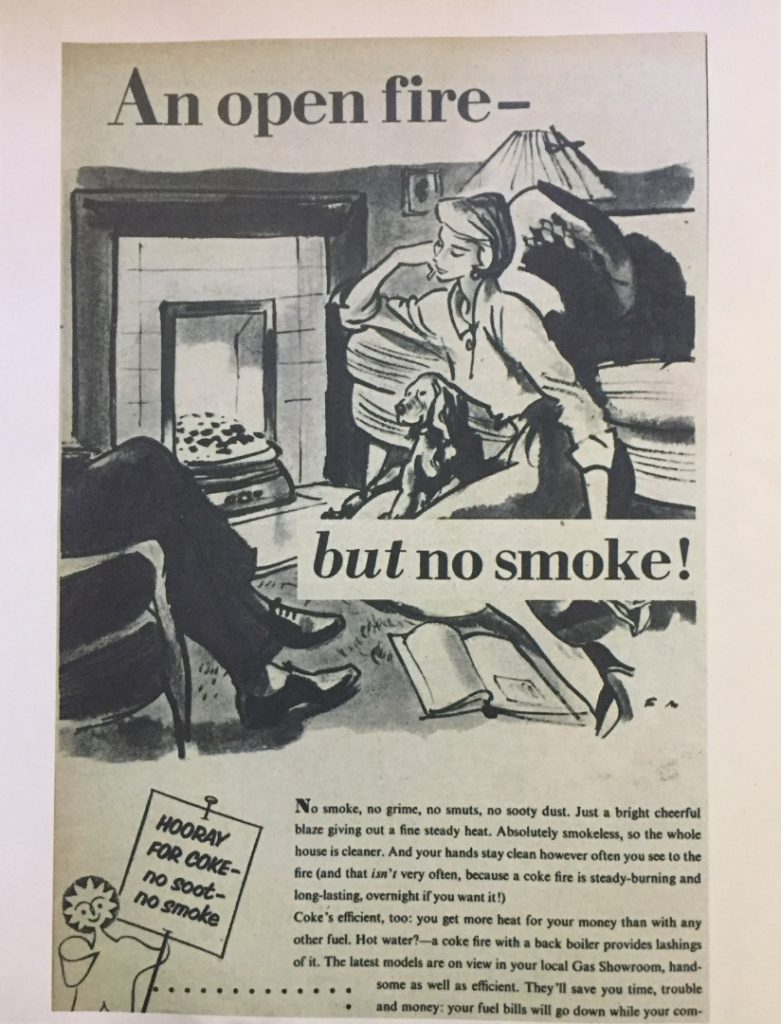

With the passing of the 1956 Clean Air Act and the introduction of smokeless zones, the race was on to sell new fuels and appliances to retailers and domestic consumers. Mr Therm, the cartoon mascot of the Gas Council since the 1930s, came into his own in the 1950s; the chirpy little gas-flame figure would put an end to fog, providing ‘An open fire but no smoke’ (see Figure 5).[4] An Orwellian fantasy of the family hearth, but updated and upgraded: a middle-class couple in an elegant, smokeless home.

It may seem too esoteric or whimsical to suggest that Mr Therm is a symbol of post-war Britain and yet he sits at the epicentre of a series of debates concerning reconstruction, the home and the family that began before the war and continued well into the second half of the twentieth century and that defined what it meant to be a nation that was both traditional and forward-looking. Since at least the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was still possible to overlook the relationship of smoke and pollution, the hearth had been a symbol of comfort and prosperity. The coal fire was the heart of the family home and was the source of physical and spiritual sustenance; in the context of war it also stood for the defended nation.[5] These images retained a powerful hold on the post-war imagination and the desire for restorative peace; they were part of a fantasy of home, family and community that had survived the war but was still threatened by external and foreign forces. Whilst it was clearly a nostalgic and even reactionary outlook, it was nevertheless an effective ideology that defined experiences and expectations in the post-war years. In an article entitled ‘No Place Like Home’, published in 1957 in the self-confessed retrogressive and sentimental annual miscellany, The Saturday Book, Olive Cook celebrated ‘…the privacy, the well-curtained windows and the cosy fire of our own home’ (Cook and Smith, 1957, p 15). In fact, this is a very 1950s take on the open fire. It is homely, private and self-contained; owner-occupied rather than a rented room with shared facilities.

Whilst marriages and families were straining to adapt to post-war domestic life, the coal fire remained a symbol of continuity and well-being and in her second Christmas broadcast as Queen, it is hardly surprising that Elizabeth II drew on its reassuring and familiar image to represent the tribulations of the Commonwealth:

When it is night and wind and rain beat upon the window, the family is most conscious of the warmth and peacefulness that surround the pleasant fireside, so our Commonwealth hearth becomes more precious than ever before by the contrast between its homely security and the storm which sometimes seems to be brewing outside…

(Fleming, 1981), p 75

These almost folkloric associations made it harder in the 1950s to legislate against domestic smoke than it was to regulate the smoke from industrial chimneys. Vested interests drew on the powerful rhetoric of the coal fire to combat the smoke pollution reports of the early-1950s and the growing inevitability of legislation. In its response to the 1954 Beaver Report on Air Pollution, a member of the Institute of [Coal] Fuel stated: ‘I refuse to be deprived of some of the things that are dear to my heart, and one of them is the open fire’; watching the flames of a coal fire, he continued, is a trigger for the romantic imagination, like ‘…watching waves break on the sea-shore – and who wanted to sit and look at the electric radiator or the gas fire?’ (Journal of the Institute of Fuel, 1955, as cited in (Thorsheim, 2006), p 180).[6] The National Union of Mineworkers was also a powerful lobby group in this period and it is possible that the Conservative Government’s support of anti-smoke legislation was motivated, in part, by the desire to curtail the power of the miners. With royalty, industry, unions and popular culture mobilising the myth of the coal fire, it was up to Arnold Marsh, General Secretary of the National Smoke Abatement Society, to criticise the ‘…viscous sentimentality that surrounds the open coal fire’ and to spell out the environmental problems created by this ‘…grand old English custom’ (Marsh, 1947, p 216). The coal fire could only assume its symbolic image as a national custom and a repository of feeling through the people seated around it and in the 1950s those people were the happy companionable couple and their family. The coal fire was part of a post-war chain of being that started with the domestic hearth and progressed to the family, the home, the nation and the Commonwealth.

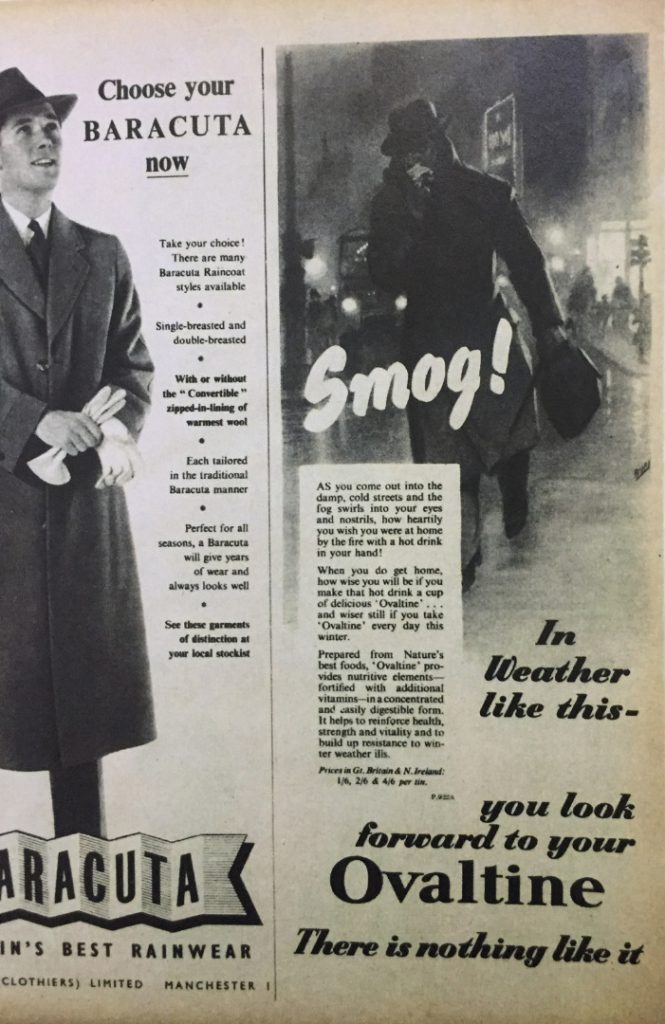

According to the American sociologist and philosopher Lewis Mumford, the Paleotechnic world of iron and coal would be replaced by the Neotechnic world of light, colour and synthetics but post-war Britain existed in the interstices of both phases of development (Mumford, 1955). No one made use of these images and developed them more effectively than the advertisers. What better way to evoke the consuming comforts of home than through their contrast with the chilly chiaroscuro of the city? In the winter months, hot drink products such as Ovaltine and Horlicks, Bovril and Cadbury’s Drinking Chocolate, ran advertising campaigns linking their brands with the restorative values of home. In December 1953, Ovaltine drew on the experience of the Great Fog with an atmospheric black and white image of a man hurrying home through a damp, dark street: ‘Smog! As you come out into the damp, cold streets and the fog swirls into your eyes and nostrils, how heartily you wish you were at home by the fire with a hot drink in your hand!’ (see Figure 6).[7] The imagined family he is rushing home to is as vivid as the choking damp air of the winter street but a few years later Ovaltine shifted its focus and depicted the world on the other side of the front door: ‘Ovaltine Families Are Happy Families’ (see Figure 7). Well-dressed, well-furnished and boisterously happy, this is the world of the domestic fireside, the safe haven from the storms brewing outside. There was, however, a more troubling possibility that the advertisers dared not hint at: perhaps the storms were not only outside the home but were also inside, creating conflict that not even Ovaltine could ease?

When post-war Britain stared into the flames of their open coal fires they saw the past and the future; a world of childhood sentiment but also of shifting gender and class positions and a growing fissure between the pre-war and the post-war nation. At the same 1954 meeting of the Institute of [Coal] Fuel, where a man had reminisced about the pleasures of staring at a coal fire, the female mayor of Tottenham suggested that this was a highly gendered amusement, and that: ‘In almost every home it was papa who wanted the comfort of an open fire when he returned from work, and it was mama who wished that electricity and gas were cheaper so that she could avoid some of the dirt caused by the open coal fire’ (as cited in (Thorsheim, 2006), p 180). One man’s cosy fireside is another woman’s labour. And there was one further element that was transforming familial sociality in these years. In its 1943 report on people’s homes, Mass Observation made the prescient comment ‘…at present the fireplace often occupies a central position in the room…and if houses are to be designed without fireplaces, some new focus may have to be found’ (Enquiry, 1943, p 137). By the middle of the 1950s, television had consolidated its place at the heart of domestic entertainment: more people owned televisions; there were new ways of purchasing or renting sets; national network coverage had grown; and there were longer hours of broadcasting. Steadily and inexorably, the television set usurped the open coal fire at the heart of family life. It could not provide warmth but it could feed the fantasy of the cosy hearth; it comes as no surprise that the virtual fireplace, with crackling flames and glowing logs and coals, is a favourite video today for smart televisions and computer screensavers. No dirt, no smoke, same dream.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text