When is a shield not a shield? Interpreting Indigenous versatility in an East End match factory

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/231905

Abstract

A wooden shield, made by a once-known Aboriginal person in Western Australia around the beginning of the twentieth century, sits in the Science Museum’s London stores. This paper focuses on its life in an East London match factory from about 1928 until 1937, when it was transferred to the Science Museum. The shield stands out among its Aboriginal counterparts now held by museums because curators at the Bryant and May Museum of Fire-Making Appliances (and subsequently at the Science Museum) did not prioritise its links with conflict or ceremony, nor the skill with which it was carved. Instead, unprepossessing marks on its back captured their attention. These saw-marks showed that this was not ‘just’ a shield: it had sometimes been used to make fire. Valued now as an example of global fire-equipment, it was subsumed into an English collection of fire making technologies. By tracing the shield’s early museum life, this paper considers how and why European collecting cultures have marshalled indigenous objects to promote narratives of supposed ‘progress’.

Keywords

Australia, collections research, decolonial approaches, exhibitions, fire, Indigenous, UK museums

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Today, a shield sits in the Science Museum’s storage facility in West London.[1] Its maker, a once-known Aboriginal person in Western Australia, painstakingly shaped and carved it from wood around the early twentieth century.[2] The shield has been on many journeys since that moment. This paper explores one facet of its rich history: its temporary residence at an East London match factory from around 1928 until 1937, when it was loaned to the Science Museum.[3]

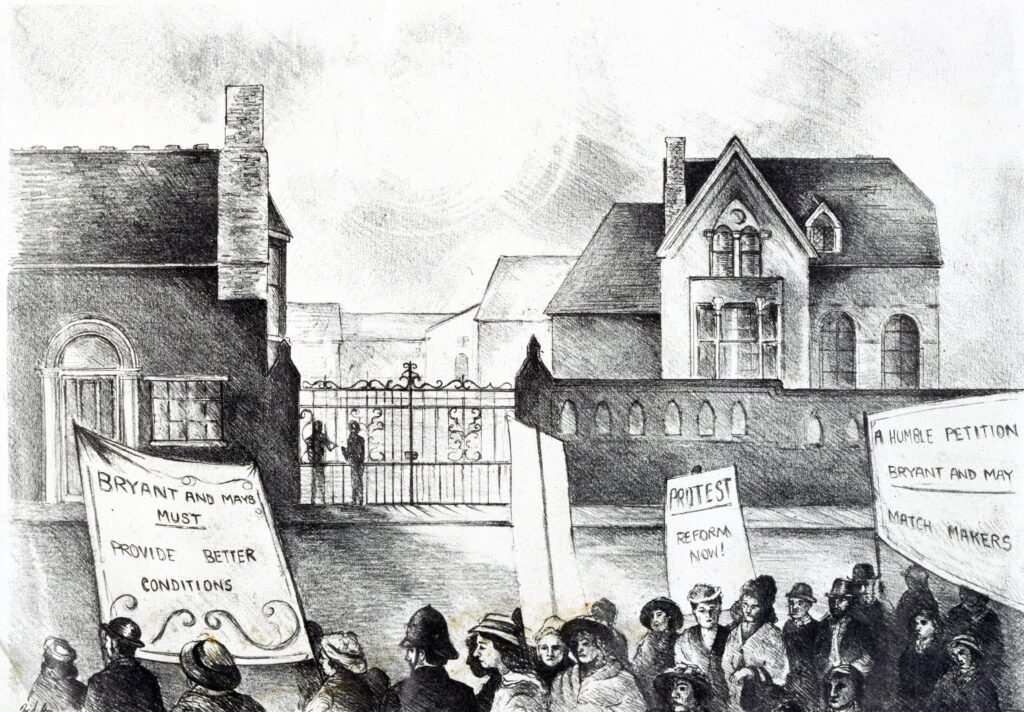

Now a gated community, Bryant and May’s old Fairfield Works factory site in Bow (Figure 1) was once the largest factory in London.

During the late nineteenth century, the factory was the scene of some now-infamous labour practices (Figure 2). These included repeated incidences of phosphorous necrosis, an industrial disease caused by contact with toxic white (or yellow) phosphorous that the company was using to make matches (Arnold, 2011, pp 624–5). Home Office investigations found that for more than two decades Bryant and May deliberately concealed uniquely high rates of ‘phossy jaw’ at Fairfield Works, with 51 workers contracting the disfiguring disease, nine fatally (Arnold, 2011, p 637). In 1901, after an 1898 prosecution and much public outrage, the company finally stopped using white phosphorous. Bryant and May’s notoriety receded in the early twentieth century, as its directors adopted less controversial technologies and management styles (Arnold, 2011, pp 628–9). In the 1920s they backed a new venture: creating a museum to illustrate the development of fire making technologies across the globe. Taking up 2,200 feet of factory floorspace, this corporate museum bolstered the firm’s claim to leadership in developing and adopting safe and innovative matchmaking technologies (Christy, 1926, p 4). The Bryant and May Museum of Fire-Making Appliances (now defunct) opened on 13 October 1926. In his opening address, company chairman George Paton proudly proclaimed that it ‘gives every known form of lighting from many centuries before Christ up to the present day, when you have the most perfect matches made – at Fairfield Works’.[4]

Corporate museums as distinctive institutions emerged around the turn of the twentieth century (Danilov, 1991, p 3).[5] These institutions are generally exhibit-based facilities owned and operated by companies, often serving public relations, marketing or other commercially relevant roles (Nissley and Casey, 2002, p 2). In Kim Lehman and John Byrom’s words, they ‘occupy a difficult and little-understood position, straddling both the cultural and traditional world of the public museum and the profit-motivated and ever-changing business world’ (Lehman and Byrom, 2007, p 1). Bryant and May employees did not directly collect most of the objects in their corporate museum, unlike some of their counterparts elsewhere. Instead, the opportunity to purchase a renowned private collection was apparently the spark that caused senior managers to create the museum. Around 1920, London-based ornithologist Edward Bidwell, ‘a well-known and respected figure at auction rooms’ (British Birds, 1930, p 247), was getting on in years and looking to sell his large collection of fire making appliances. Some contemporaries felt the collection should ideally have gone to a national museum, but evidently by 1923 any negotiations on that front had fallen through (H.S.H, 1927). George Paton, who had first seen Bidwell’s collection in the 1900s, therefore recognised the ‘distinct danger of the collection passing out of the country’.[6] At the Bryant and May Museum’s opening ceremony he happily recounted that ‘Mr. Bidwell [had] agreed with us that the home for such a collection of treasures was the home where the best modern matches were made’.[7] Bryant and May purchased Bidwell’s collection in 1923 for £3,800.[8] They also hired another private collector, Miller Christy, to curate the museum as a whole, and to work with Bidwell to catalogue the latter’s collection. Corporate museums are designed to have commercial relevance in a way that other private collections may not, so Christy’s curatorial task by necessity included presenting the long history of fire making in a way that complemented the company leadership’s current interests and operations.

The new museum at Fairfield Works, with its several thousand objects acquired from Bidwell and some additional collectors, was used to convey two core messages: Bryant and May’s dominance in industrial matchmaking, and the near ubiquity of fire making methods throughout humanity. Within specially made cases, objects from around the world were grouped together to represent techniques: tinder, wood-friction, flint-and-pyrites, flint-and-steel, quartzite-and-iron, optical, compression and chemical methods; and finally, the friction match. A racialised display narrative emphasised flint-and-steel methods and the friction match, invented by English chemist John Walker.[9] Christy, the museum’s first curator, explained that the ethnologist and anthropologist ‘needs to know by what means, not only the barbarous men of early times, but also the savage and semi-savage men of modern times, have been or are accustomed to supply themselves with one of the prime necessities of existence’; whilst methods ‘devised by civilized people’ were of greater interest to archaeologists and historians, ‘from the flints-and-steels associated with the troublesome tinder-box of our grandparents to…the familiar friction-match of the present day’ (Christy, 1926, p 3). This overarching narrative of technological progress also helpfully obscured Bryant and May’s controversial entanglement with white phosphorous (Figure 3).

Nick Nissley and Andrea Casey have considered corporate museums’ strategic relevance as a politicised form of organisational memory (Nissley and Casey, 2002). The ways in which corporate museums fashion organisational memory, they argue, shapes the identity and image of the corporation in question. I have found no evidence that Christy’s employers explicitly instructed him to downplay their company’s long phase of using white phosphorous despite the availability of less toxic alternatives. However, the curator would have understood that he had to navigate a contentious corporate history. The ‘politics of memory’ can manifest in corporate museums through the conscious or unconscious ‘forgetting’ of past scandals (Nissley and Casey, 2002). Troubling events may be skipped over or downplayed, as some German corporate museums have more recently been accused of doing in relation to companies’ activities during the Second World War (De Syon, 1999, p 119). In the Bryant and May Museum, a display narrative that focused on technological innovations cast a veil, consciously or unconsciously, over senior managements’ choice for the company to remain a relatively low technology matchmaker for the last two decades of the nineteenth century, despite the damage this did to workers (Arnold, 2011, p 625). Instead, the museum was designed to frame Bryant and May as the leading manufacturer and innovator of the modern day: creator of ‘the most perfect matches made’.

Making fire and ‘marking progress’

At its opening, the Bryant and May Museum held several objects made by Aboriginal people from Australia. It used them to help promote its overarching narrative about the universality of fire making, and humanity’s progress in creating and refining technologies culminating in the safety-match (which used nontoxic red phosphorous and was safer for workers and users).

The new museum organised its displays typologically, with little move to group objects strictly according to their place of origin. This approach was very similar to that of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (founded in 1884). When General Pitt Rivers gave that museum its founding collection, he placed a then-unusual requirement on it: that the objects must be displayed according to ‘type’ or function, rather than according to their originating group or culture (O’Hanlon, 2021, p 18). Subsequent curators such as Henry Balfour worked with the displays and developed or questioned the principles behind them (Morton, 2012, p 375), but the inherent focus on typological series means, as Haidy Geismar remarks, that ‘within its cases, even today, hundreds of years of human history are compressed into an object lesson of Darwinian-inflected cultural progression from primitive to modern’ (Geismar, 2018, p 2). The use of typological series to display objects was racially inflected, given that contemporary theorists frequently used stadial progress theories (the notion that populations progress from stages of ‘savagery’ or ‘barbarism’ through to ‘civilisation’) to explain apparent cultural and technological differences between human societies. Edward Burnett Taylor, an anthropologist closely connected with the Pitt Rivers Museum, had propounded a theory of Aboriginal Tasmanian peoples’ ‘extreme primitivism’ based largely on studying a single stone tool (Taylor, 2016, p 321). When curating the Bidwell Collection, Bidwell and subsequently Christy were undoubtedly influenced by their knowledge of the Pitt Rivers Museum and its curatorial emphasis on typological series. By emphasising a technological evolution of fire making that culminated in ‘modern’ European methods, the Bryant and May Museum situated indigenous techniques as representative of an early or primitive stage of technological development. This approach implicitly reflected pervasive ideas about the supposed racial and cultural hierarchy of humanity.

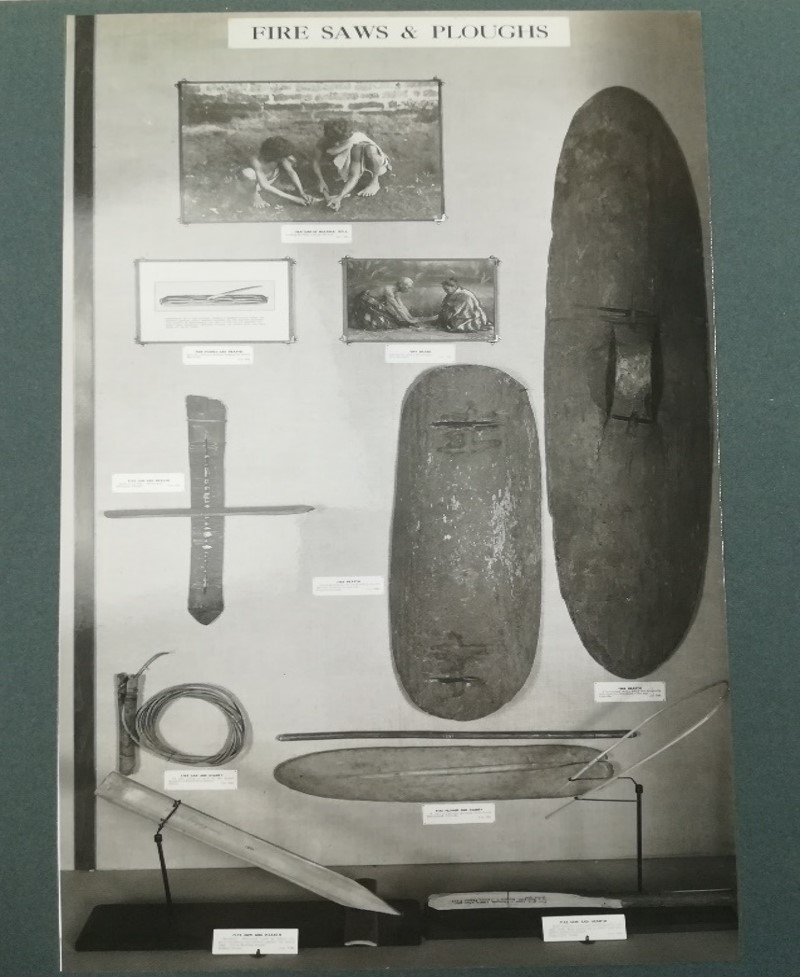

Sometime before 1937 a wooden shield (Figure 4) joined the collection. Multiple forms of fire making tools are found across Australia, and Christy included several examples in the Museum’s cases devoted to wood-friction techniques. This shield first appears in a photograph of the ‘FIRE SAWS & PLOUGHS’ section taken some time between 1926 and 1937 (Figure 5). It appears alongside items from India and Oceania, including two photographs of Maori people of Aotearoa New Zealand and Paniya people of India.[10]

Although it is the largest item in this section, the shield has the shortest label, which reads simply: ‘FIRE HEARTH. A ceremonial shield which has frequently been used as a hearth for a fire saw. Australia. 109.’[11] It hangs next to a smaller shield from central Australia, with both objects positioned to show the saw-marks on their backs.[12] The fire saw method would have involved putting tinder (such as dry grass) onto the shield and then rubbing wood (sometimes the edge of a spear thrower) rapidly against it to create combustion. However, relevant tinder and sawing implement(s) were not displayed alongside the two shields. Instead, the marks alone were used to testify to their relationship with fire. The absence of tinder is not surprising: such materials are not known for their visual variety and were presumably deemed to be of comparatively little interest to museum visitors. However, the decision to display only the ‘hearth’ rather than its essential accompanying elements might also be connected to widespread European perceptions of Aboriginal people as being nomadic wanderers who carried little.

Whilst Aboriginal shields are found across many ethnographic collections, this one is near-unique in having been deliberately acquired as an example of fire equipment. It was probably made by an Aboriginal man from Western Australia, although his name is no longer known and his Country cannot yet be known for sure.[13] Later it probably passed through the hands of several collectors, perhaps including Bidwell. The ornithologist had worked closely with Christy to prepare a catalogue of the new museum’s holdings (published in 1926; supplement published in 1928), which included eleven Aboriginal fire making tools (Christy, 1926, pp 19–20; 22). The shield was not among these, suggesting it was acquired after 1928; although it is possible that Christy’s ailing health led to some compromised record-keeping before his death in January 1928. The lack of information recorded in the shield’s label stands out even compared with other poorly documented Australian items in the collection, which generally the museum at least linked to a particular Australian colony or state. Some collectors’ names were recorded, for example in the case of a hearth and two fire-drills ‘collected by Mr. Carton Lee; Cairns District, North Queensland’.[14] The lack of recorded information about the shield discussed here suggests that its ‘field’ collector was not a direct associate of Christy, Bidwell or the firm’s managers. It may well have been sold by a London auction house, for these businesses did not generally record the provenance of Aboriginal objects in detail. Despite this lack of clear provenance, however, the shield demonstrates the benefits of studying objects’ changing functions and values through time, and how museum settings can highlight or obscure this. In focusing so closely on its role as fire equipment, information embedded within the shield concerning its provenance, use and significance was overlooked or ignored by curators.

Re-enactment and performance

The shield is larger, more time-consuming to make, heavier and bulkier than many simpler forms of hearth.[15] Ironically, given its later inclusion in the Bryant and May Museum, the shield’s maker would not have intended its primary role to be that of a functional hearth. Aboriginal shields, often still classified in museum catalogues under the deceptively simple category of ‘weapons’, are in fact highly multifunctional objects. Kim Akerman points out their importance not merely as defensive devices: they can serve as a key symbol of a mature male, and as ‘necessary accoutrements in some types of ritual performances, particularly those in which the exploits of shield-bearing ancestors were re-enacted’ (Akerman, 1992, p 16). Owners may produce fire either by drilling a rod into the wood or by sawing a woomera (spear thrower) back and forth over the surface to create frictional heat. Gaye Sculthorpe points out that despite their robust nature and thus frequent survival in museum collections, few shields have been well-studied either in relation to their design or individual histories (Sculthorpe, 2021, p 131). Even less attention has been given to their potential use as hearths, with historians generally focusing on shields’ decorations and roles in hunting, conflict or ceremony.[16]

Throughout its time at the Bryant and May Museum and the Science Museum, the shield has been presented as an object used by Aboriginal people to create fire. However, they were not necessarily the only people to use it in this way. Some Euro-American collectors and museum anthropologists used indigenous fire making equipment to re-enact the making of fire.[17] Henry Balfour, curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum between 1893 and 1937, and Walter Hough of the Bureau of American Ethnology, made and exchanged many models of fire making equipment for use in experimental re-enactments (Isaac, 2010). Balfour would also use original equipment: in 1907 he discussed a Burmese fire piston (a hollow cylinder used to rapidly heat air and thus ignite tinder) that he had recently been given. The piston had been accompanied by a bag of vegetable floss tinder, he wrote, ‘with which I have been able to produce fire with considerable ease on many occasions’ (Balfour, cited in Larson, 2006b). The curator certainly had many possibilities to choose from, as over his lifetime he acquired 1,758 fire making objects from around the world (Larson, 2006b). Bidwell and Christy both gave fire equipment to Balfour, and the three men corresponded with each other over their passion. Reviewing their correspondence, Frances Larson suggests that Balfour had even at one time sought to combine Bidwell’s whole collection with his own (Larson, 2006a). In sustaining the relationships between enthusiastic curators and collectors, objects were not only looked at and held: sometimes, they were used.

Turning the shield over

Alain-Michel Boyer argues that across many societies the shield ‘is an object to be shown and exhibited’, and this is supported by the fact that so many cultural representations depict them from the front (Boyer, 2000, pp 15–6). Within and beyond Australia, scholars and artists have likewise tended to focus on Aboriginal shields’ fronts. However, this object’s positioning and labelling in the Bryant and May Museum (and subsequently the Science Museum) unusually privileged its back, for this contained the marks that proved its link with making fire. William O’Dea, an Assistant Keeper at the Science Museum, even categorised it as a hearth first and foremost. In a 1937 list of items that had not been recorded in Christy’s 1926 catalogue or 1928 supplement, O’Dea called it a ‘Fire Hearth in form of a ceremonial shield – Australia [my emphasis]’ (O’Dea, 1937). Neither its Bryant and May label or O’Dea’s list described the shield’s front, which few who visited the museum at Fairfield Works would have seen (Figure 6).

Turning the shield to its front reveals a striking zigzag pattern carved across seven sections. Shield designs with longitudinal zigzag lines are closely associated with Aboriginal peoples of Western Australia, and particularly with communities along the north-western coast (Figure 7). Most scholars agree that they were probably made in the northwest and then often moved inland through extensive Aboriginal trade networks that criss-cross the continent (Akerman, pp 16–9). The woonda or wunda shield featuring just three sections of lines is closely linked with Yamatji peoples of the Murchison and Gascoyne regions of Western Australia (Akerman, pp 16–7). It is the best-known design of this type, with examples found widely across Australia and in many museum collections around the world. Shields with seven sections, like the Bryant and May shield, are less widely known.[18] One example now in the Western Australian Museum was registered by that museum in 1912. It was donated by a Mr Grundy from the Pilbara, and may originate from the Yindjibarndi people whose Country lies around the Fortescue River.[19]

It took time to carefully carve this shield’s long parallel grooves and accent them with white and reddish-brown pigment. The design contains practical as well as symbolic significance. When used in fighting, parallel grooves help to deflect spears thrown with a woomera. They also hold rich cultural meaning for many communities in Western Australia. Akerman notes that ‘multiple zigzags on shields and other objects have been variously interpreted as marks left in the sand by an ebbing tide, flood waters, and the ripples created by the wind on the surface of the sea and large bodies of freshwater’ (Akerman, 1992, p 17). Rain and water, essential to life, form a common thread through these diverse cultural associations. The shield’s potential links with ceremony are beyond this article’s scope, but suffice to say that material culture, even supposedly ‘mundane objects of everyday use’, may, within Aboriginal traditions, carry very meaningful connections with ceremony and spirituality (Pickering, 2015, p 431). Whilst its first owner presumably carried the shield openly as something that non-initiated people were permitted to freely see, this did not necessarily make it an item that those people could freely understand.

Conclusions

Places are important to understanding different interpretations of objects’ cultural and technological significance; this is particularly the case when we consider how this shield has been displayed in London. Most western collectors were far more interested in Aboriginal shields’ frontal decorations than in their traces of use. Reviewing London auction catalogues from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Philip Jones suggests that buyers usually found Aboriginal material less desirable than African and Pacific material, but that decorated shields were a notable exception (Jones, 2018, p 142). Yet within the Bryant and May Museum, the saw-marks on this shield’s undecorated back unusually became more highly valued than any other part of it. Like the typological fire making displays at the Pitt Rivers Museum, its specific geographical origins were framed as less important than the type of technology and thus the human culture that it represented. It therefore became part of a display that promoted an idea of a basic human universality, but also the notion that certain peoples had now attained far higher stages of technological progress. Within this space indigenous technologies were contrasted with, and numerically dominated by, products of supposedly ‘civilised’ western cultures.

Literature on the important role of managed fire in Australia generally focuses on land and species management practices (Figure 8), and particularly on cultural burning knowledges and practices.[20]

The role of historic fire-equipment such as shields has been less widely discussed.[21] Yet these items fundamentally challenge western museums’ conventional approaches to categorisation. The shield confounds such narrow definitions as ‘weapon’, ‘tool’ or ‘ornament’, as its original owner or owners would have used it in multiple ways. The making of fire was one facet of a complex history. Philip Jones suggests that ‘now taken for granted in western culture as the easy gesture of “striking a match”, Aboriginal fire making was never a casual matter. In Aboriginal societies the fire-drill and the fire-saw methods had the concentrated intensity of a small ceremony, a tiny miracle’ (Jones, 2017, p 192). For Miller Christy, the production of fire was also deeply significant: ‘Indeed, without fire and the means of making it, Man could hardly claim to be regarded as human’ (Christy, 1926, p 2). Within the Bryant and May Museum, the shield was thus framed as part of a collective human achievement, but also an example of ‘primitive’ practices superseded by the ever-superior methods of ‘civilisation’.

Today Aboriginal shields are rarely used for their original purposes, with a few exceptions in remote communities of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and northern South Australia (Sculthorpe, 2021, p 139). However, explains Sculthorpe, ‘old shields in collections have inspired the work of contemporary Aboriginal artists, generating new values and meanings’ (Sculthorpe, 2021, p 139). In 2015 Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones reflected that ‘shields and other objects in collections are gifts; gifts from our ancestors left to aid us on our new journeys and to become the springboard for many contemporary practices and understandings’.[22] Such objects point to the possibilities of understanding material culture and those connected with it in more nuanced ways. Ngemba carver Andrew Snelgar explains that:

You never see two traditional shields that are the same, they’re all individual by the maker’s hand, inspired by the object or the piece, but also your connection with Country and totems, bloodlines, groups. There’s story that you can interpret from them.[23]

As this paper has sought to demonstrate, rich and unexpected meanings materialise when curators stop thinking of an object as ‘simply’ one thing or the other. Even the simple act of turning it over may reveal new possibilities. Many other objects now in museums are likely to benefit from this approach. In 2020 a Maasi delegation visited the Pitt Rivers Museum, where teacher and activist Amos Karino Leuka noted that a Maasi firestick was ‘wrongly displayed’ because it had been positioned to show the colonial text written on it, rather than its actual drill-holes – thus obscuring the object’s ‘true meaning’ (Pitt Rivers Museum, 2020). As museums seek to become more equitable spaces, there is a need to question long-held assumptions about which aspects of an object’s appearance should be prioritised in displays, and to ask what messages this positioning conveys.

In 1937 the Bryant and May Museum closed, with its collection sent on long-term loan to the Science Museum in South Kensington.[24] The collection was formally given to the Science Museum in 1996 and renamed the Wilkinson Sword collection.[25] The shield now sits in the Science Museum’s storerooms at Blythe House in West London, awaiting transfer to a new storage facility at Wroughton, an ex-RAF base in the Wiltshire countryside. This new journey speaks to further unanticipated synergies with its boundary-crossing nature: once owned by Wilkinson Sword, a company that manufactured guns before famously moving into swords and shaving razors; now imminently to be housed in an ex-military facility that has been transformed into a centre for cultural heritage.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Gaye Sculthorpe and my two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments and suggestions, and to Moya Smith and Ross Chadwick for generously sharing information about similar shields in the Western Australian Museum.