Private portraits or suffering on stage: curating clinical photographic collections in the museum context

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160503

Abstract

Medical photography collections often remind us of the inescapable reality of human suffering and pain, and at the same time they oblige us to deal with questions of ownership and privacy. Medical photography collections are thus considered ‘sensitive’ collections within the museum context. This essay investigates privacy issues involved in the curating of historical photographic collections in museum spaces. When medical photography entered into non-medical domains privacy issues emerged. It is these privacy issues that cast a shadow of sensitivity on the medical material. But the relationship between clinical photograph collections and museums is not as straightforward as it may seem. Personal pictures involve power and privacy, and both aspects play a role in the public display of historical medical photographs, often in unexpected ways.

Keywords

clinical photography, Curating, ethics, informed consent, medical photography, patients, privacy, sensitive collections

Private portraits or suffering

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/160503/002On a dark day I went to see the patients. In a closed chilled room, I inspected a spectacle of bodies, caught in corsets, staring at me, they were passing before my eyes like in a parade. But they were patients on glass, flat and hard to the touch, only visible when held toward a light source. I sat in one of the rooms at the depot storage of the Boerhaave Museum in Leiden, looking at patient images on black and white glass negatives. And I wondered, how can I as a curator share these fascinating but personal images with others in a meaningful way? Two aspects seemed to hold me back. Firstly, clinical photographs[1] are fascinating and educative in many ways, but appear somehow to carry a part of (the history of) that person (Biernoff, 2012). Clinical photography, as modern photographer Ian Berle concisely defined, ‘is used to record disease, dysfunction and trauma’ (Berle, 2008). By putting such images on public display, is there a violation of privacy at play? Secondly, I pondered on the role and responsibility of a museum of the history of medicine in staging images that feel private because of their intimate subject matter in a public exhibition space. These issues are at the basis of this paper and come together in the act of curating – ‘to care for’ – historical photographic collections in exhibition spaces.

Medical photographs feature regularly in exhibitions in museums of science and medicine, libraries or war museums.[2] Yet often the photographs on display are treated or presented as if they were either standalone artworks or illustrations to objects, and not themselves treated as objects, distributed and functioning in a diversity of practices and localities. Neither is the act of looking – what happens between the spectator and the image within the museum space – made into a topic to address explicitly. Focusing on their aesthetic qualities, historical medical photographs have on occasion been displayed in museums or galleries in art-historical settings.[3] However, scholars have criticised the isolation and absence of reflection of the social institutional historical uses of medical photographs (Cross & Peck, 2010). The question arises of how historical uses of medical photography echo throughout exhibition practices.

Clinical photography collections, I suggest, are ‘sensitive’ collections within the museum context. I argue that patient photographs belong to the same family as colonial objects, colonial photography, war photography and human remains.[4] The family ties that bind these materials are characterised by a constant confrontation with suffering, questions of ownership or (a lack of) control thereof.

When medical photography entered into non-medical domains privacy issues emerged. It is these privacy issues that cast a shadow of sensitivity on the medical material. Consequently, privacy considerations also play a role in the public display of historical medical photographs. Indeed, museums themselves actively move these images into a different context of display and use than that for which they were originally produced. Museums thereby activate a continuous balancing act, where a thin line between exhibiting and exposing emerges. It is my purpose in this article to inform museum workers and historians in the field of history of science and medicine about the specific issues involved in medical photography in museum contexts and to discuss how displaying these images involves and unravels more than you might initially think. The relationship between clinical photograph collections and museums is not as straightforward as it may seem. Personal pictures involve power and privacy.

Let us follow an image made of one of the glass patients from its creation to today. The journey takes us from a 1920s seaside tuberculosis sanatorium via photographers and physicians exploring ways to record patients, to privacy discussions and the rediscovery of long forgotten images. I will first discuss the historical context of privacy and clinical photography. Subsequently I explore the current curatorial questions and exhibition ethics for displaying historical clinical photographs. The possible encounters between patient P in a museum gallery with spectators one century after the creation of the image forms only the start of new journeys to come. The key to understanding such contemporary settings of the image, I contend, also lies in its historical context.

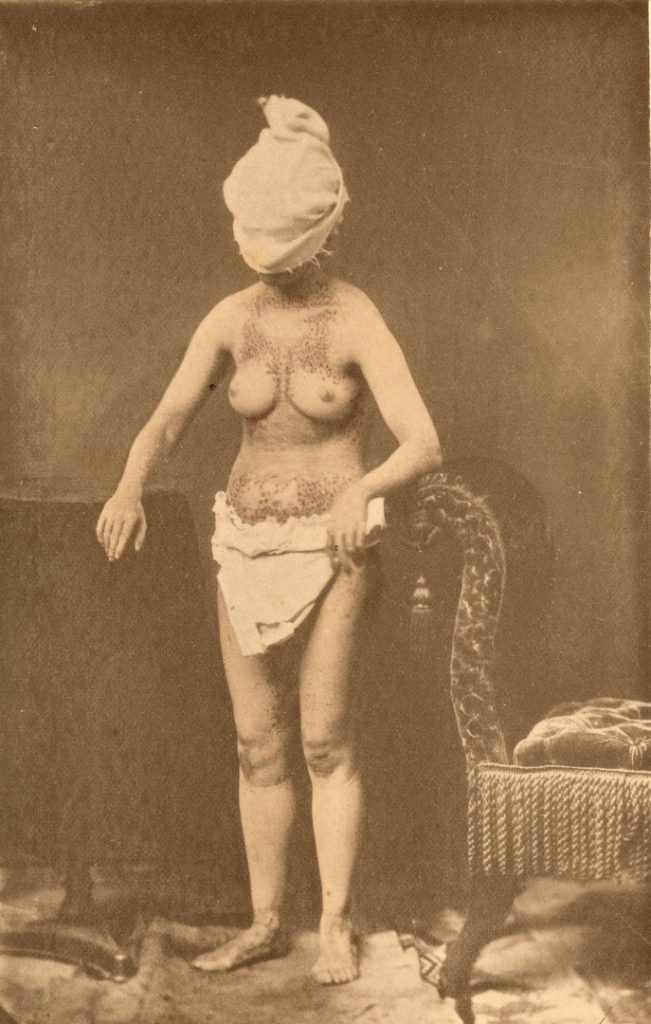

This image of patient P is part of a Dutch collection of glass negatives with clinical images from the early twentieth century.[5] Made in a Dutch seaside sanatorium for young children suffering from tuberculosis, the collection contains 255 boxes with almost 3,000 glass negatives dated between 1908 and 1940. Partly clinical images, partly X-rays, the images cover a broad range of visual signs of tuberculosis, internal and superficial. As with the other clinical images this example was probably made by the director of this institute, the Rotterdam Zeehospitium. In 1922, the female director Van Dorp-Beucker most likely wanted to minutely fix and closely monitor P in order to clinically follow the consequences and development of her battle against the tuberculosis infection. In 1922, at the time the image of P was taken, physicians and photographers applied photography to document a wide range of what was considered as outward visible pathology. From skin diseases to war trauma, psychiatry, tropical infections and orthopaedics, the clinical photograph of the patient was increasingly used to record disease progression. Similarly, the photograph of P functioned as evidence of the healing process. In her photographic image she revealed her skin wounds on the forehead and shoulder whilst seated on a treatment table.

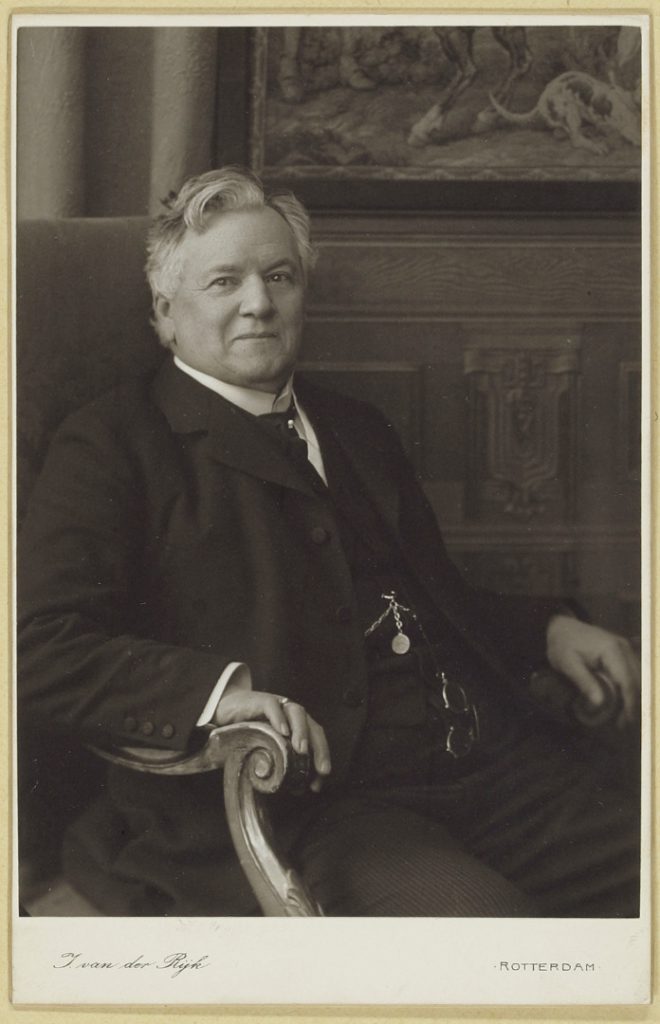

The clinical images become part of the patient file – a most intimate personal document for recording patient histories. Such a personal, be it temporal, record of this patient’s often painful struggle with a disease heavily contrasts with the voluntary sitter of the physician’s portrait.[6] A demonstration of one’s professional authority versus revealing pain and trauma. The patient file documenting bodily trouble set against the physicians’ carte de visite in a collector’s album highlights a division of power. In the first photograph (see Figure 2) Dr Halbertsma, an eminent Dutch physician, shows himself perfectly groomed and ready for fame. In the second photograph (see Figure 3), a young half-naked boy who stayed at the TB sanatorium demonstrates his visible wounds and scars inflicted by the disease. In both cases, the representations exercise a strong individual agency.

Even in the early days of clinical photography some physicians worried about the so-called ‘indecency’ of some patient images and their ‘direct’ documentation. From the middle of the nineteenth century, many physicians embraced photography as a technology with great potential. Low costs, accurate representation, and life-like depiction of patients were seen as the most important advantages. Physicians considered accurate images as indispensable clinical tools for teaching and promoting emerging disciplines such as dermatology.[7]

During the explosion of photography in the 1900s, the newly found way to depict patients became contested. One example painfully brought this to the surface. The American dermatologist George Henry Fox used his photographs of patients with skin diseases in talks he held at medical societies in the United States and Canada. After one of his lectures, the operator of the lantern-slide projector came up to him and said: ‘Say, Doctor! One of those women’s faces shown on the screen was the very image of my sister-in-law.’ In his memoires Fox recounts how uneasy he felt at the time because he ‘remembered that a picture of a private patient taken with the assurance that it was not intended for publication had somehow got into the collection of cases from [his] clinic and that this particular patient came from this very city’ (Fox, 1926). This fascinating incident indicates the kind of reactions provoked by non-medical audiences encountering medical subjects in projected images. The unease felt by Fox also hints at a desire to protect his patient against unwanted onlookers.

With the introduction of the Kodak hand-held camera in the 1880s a new era of pictorial representation and amateur photography was established. These new representation practices urged a small group of doctors to debate the popularity of medical photography. They argued that photographs were used too often and patients were unnecessarily exposed. A plea for ‘decency’ said that ‘the scope of the photograph should be confined to the parts in which the phenomenon noted occurs; that the rest of the body, being unnecessary to the demonstration, be left out of the field, or be suitably covered up’ (Medicus, 1894). Besides indecency, revealing the patients’ identity was also seen as a key problem: ‘Not that all these pictures […] are objectionable on the score of indecency, for they are not; but they are or appear to be of such character as to be capable of revealing the patient’s identity, which should always be avoided. […] The sanctity of the person should never be violated save as a matter of necessity. This is no new dictum. The medical profession has always recognized and endorsed it, but thoughtlessness now and then allows the camera to beguile an individual into its infraction’ (Medicus, 1894).[8] Medical illustrators had gone ‘photo-mad’ (Keiller, 1894) and fear mounted that the circulation of medical photographs would stretch beyond the educated eye of the professional. Surely, no patient wanted to become a celebrity: ‘The normal man and the normal woman shun the notoriety that comes from public exposure of the person, and nobody has the right to thrust such notoriety upon them’ (Editorial, 1894). Where does this leave the re-appropriation of these photographs in a contemporary museum? I will elaborate on this further on.

The discussion on the boundaries of medical photography at the end of the nineteenth century coincided with new concerns about privacy. In a ground-breaking article on the right to privacy in the Harvard Law Review (1890) two American lawyers pointed to the right of the individual ‘to be let alone’ (Warren & Brandeis, 1984, pp 75–103). According to lawyers Warren and Brandeis, the new urge to define the boundaries between public and private was prompted by the dangerous invasions of new inventions and methods:

Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life. […] For years there has been a feeling that the law must afford some remedy for the unauthorised circulation of portraits of private persons; and the evil of the invasion of privacy by the newspapers, long keenly felt, has been but recently discussed by an able writer.

Warren & Brandeis, 1984, p 76

The publication heralded a significant early connection between the emergence and dissemination of instant photographs and the right to privacy. The ability of people to make photographs anywhere, at any time, and of anybody, was accompanied by the possibility that photographs might be circulated among a wide audience. The similarities between discussions on privacy and clinical photography at the time – and even today – are striking.

To some extent, standardisation of medical photography practices followed from the first steps towards specialisation that were taken in the early twentieth century. Many hospitals were equipped with their own photographic studios and specialists in medical photography. A first handbook on the subject appeared in 1893 and soon the convention of a plain ‘neutral’ backdrop, typical positioning and anonymization of patients followed.

Cases where a mask, a cloth, glasses or any other device was used to mask the identity of the patient increased around 1900. Yet in many smaller institutions, conventions were local, ad-hoc and less clear cut. Museums and archives here and now are filled with collections similar to the amateur images from the tuberculosis hospital. Clinical collections dating from before the 1950s mostly lack any current day standards of close-up, structural anonymization, let alone practices of informed consent. Although when it comes to informed consent we cannot be sure in most cases. Some research suggests that in a few documented cases physicians did seek permission for publication of the patient’s photographic materials. But especially with patients from a low status background, consent was most likely not actively sought at all. Conventions in pictures like those of patient P seem limited, apart from the black cloths occasionally used to create a uniform backdrop. While the lack of conventions on the one hand add to the beauty and intriguing aspects of the images, they also cause us to shift away from the original purpose of the photograph: a clinical medical record.

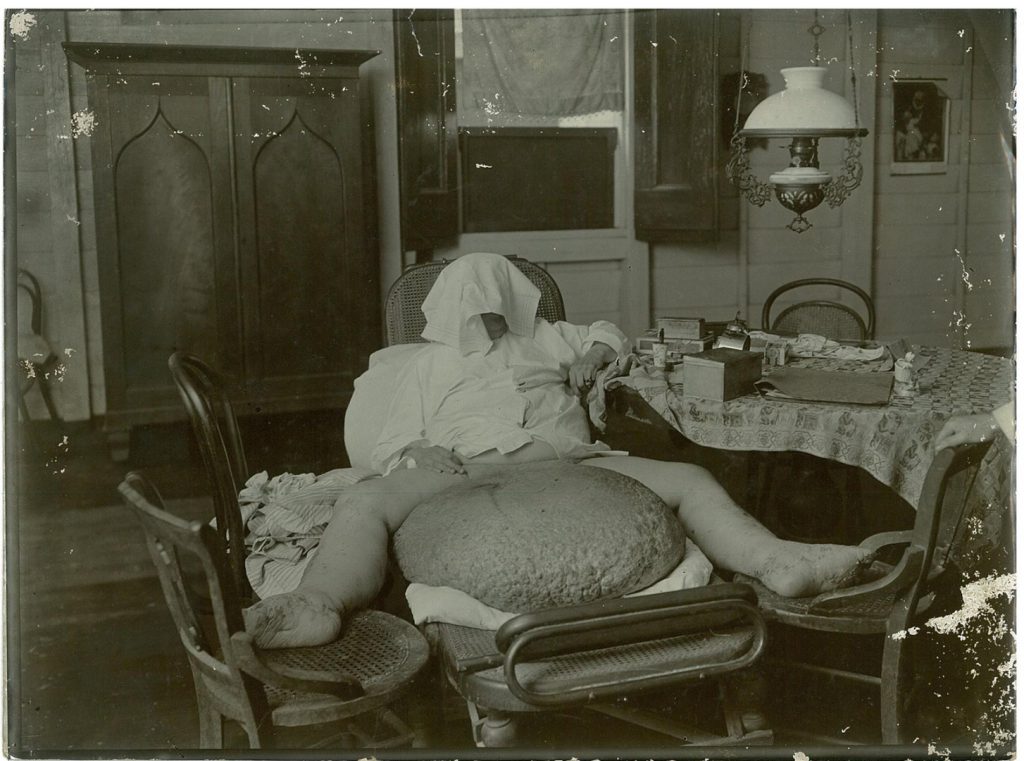

In clinical photography, power plays an important role. The anonymization of patients in the late nineteenth century does indicate awareness for the protection of the patient’s identity. By covering the face of the patient, the physicians and photographers attempt to regain control over the unruly framing of the image by the spectator. The necessity for protection does not only seem to differ with the social background of the patient, but also with the exposure of a particular affected area. Here (images below), in the hospital of the Dutch colony Surinam, photographs were taken on the spot without a proper studio. Mark the different framing of the male patient with elephantiasis of the scrotum and the depiction of two women with swollen legs, due to elephantiasis, accompanied by a nun nurse. Reasons for these differences in anonymisation possibly depended on race and the area of the body affected.

Anonymized pictures tell us about viewing practices, about the lack of control over what it means to others wherever or whenever they see these pictures. It testifies to the tension in clinical images between the continuous shifts in meaning and political framing. Does an image of the male patient with elephantiasis appal us because it shows a sensitive body area under attack, left by ‘primitive’ medical practices to take monstrous proportions? One could also argue that the photograph demonstrates a characteristic colonial case of tropical disease at a time of emerging photographic techniques. Or, when shown side by side with a more recent mild case of the same disease the image might as well function to demonstrate our advances in medicine.

Changes in framing of historical medical photographs started when images like the one of patient P were shifted away from the clinical medical gaze. In the case of patient P, this began when her image was stored after she had long left the sanatorium, collecting dust while the world around the collection of glass negatives changed profoundly.

After the Second World War medical organisations and photographers’ societies in the United States and Europe erected specific professional bodies concerned with medical photography. The Royal Photographic Society in the United Kingdom, for example, established a Medical Group in 1946. Within eight years after the end of the war at least seven organised medical photography departments were established in the UK alone (McFall, 2000). The first international conference for medical photography and cinematography was held in Germany in 1960 (Orbach, 1962). This conference marked a definite professionalization of medical photographers as specialists, who concerned themselves as professionals with audio-visual representation in the widest sense.

Simultaneously, alongside the organisation of medical photographers was an increased awareness of patient rights. Informed consent as a principle has a history in the legal sense from the early twentieth century, with a first US landmark case about a surgical procedure in 1914 (Faden & Beauchamp, 1986). The term ‘informed consent’, however, was first used in a 1957 case. Only in the 1970s did informed consent slowly become part of standard medical practice, including asking patients to consent to clinical photography. A new medical ethics emerged with a debate around authority and the doctor-patient relationship in the context of urgent societal concerns around civil rights, women’s rights, the consumer movement and the rights of prisoners and the mentally ill (Faden & Beauchamp, 1986, p 87). Nazi atrocities and the following Nuremberg Code formed a model and influence for debates on the autonomy and rights of patients.

While confidentiality of patient information has traditionally been an integral element of medicine, the concept of ‘medical secrecy’ changed with emerging public health practices in the late nineteenth century, as Andreas-Holger Maehle has argued (Maehle, 2003; Maehle & Prangofer, 2010). Yet the modern concept of confidentially in relation to authority of the patient has more prominently been framed within the 1970s and 1980s discourses of the modern patient-doctor relationship, patient rights and bioethics. This eventually culminated in our current understanding of how clinical photography ‘evokes an invasion of privacy […] because it reveals particularities that people would rather keep hidden. Professional clinical photographers […] will not photograph a patient unless he or she has explicitly given their consent’ (Berle, 2008, p 90). In the current information society, however, the wish to carefully document consent for the use of clinical photographs for teaching or publication meets ever new challenges. Research demonstrates, for example, that most patients nowadays do not feel comfortable with doctors using smart phones or other mobile devices for taking clinical photographs (Schumacher & Irwin, 2010; Bryson, 2013).

Historically, clinical photographic collections thus form sensitive collections in the context of medical ethics and legal thinking.[9] However, I suggest that clinical collections are not merely sensitive collections following from the developments in medical ethical frameworks, but also from new curatorial and museological thinking and practices.

Medical photographs of patients had been around for a long time before ethics formally entered the museum. The ICOM Code of Professional Ethics was adopted in 1986 and revised and retitled from 2001 as ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums. Article 4.3 of the Code on exhibition of sensitive materials reads that ‘Human remains and materials of sacred significance must be displayed in a manner consistent with professional standards and, where known, taking into account the interests and beliefs of members of the community, ethnic or religious groups from whom the objects originated. They must be presented with great tact and respect for the feelings of human dignity held by all peoples.’ Post-colonial and feminist perspectives especially have clearly marked a new step in the way museums now agree to deal and interact with communities, their interests and rights.[10]

How do public institutions deal with clinical photographs compared to other types of ‘sensitive materials’? Clinical photographs can be of an explicit nature, showing horrifying war-wounds, graphic pathologies, affected genital areas or patients in extreme distress. In a recent article Helen Wakely and Carly Dakin of the Wellcome Library and Wellcome Trust proposed a new approach for assessing the sensitivity of images at the Wellcome Library that are made available for research (Wakely & Dakin, 2015). They discuss many aspects that would determine material as ‘sensitive’, such as sensitive content (for example, nude children, pathology, vulnerable patients, and recognisable individuals since deceased). Other aspects discussed by Wakely and Dakin are the protection of personal data and consent, as is sensitivity in a general sense: the identification of individuals in medical photographs could cause distress to the close family, for example (Wakely & Dakin, 2015 p 54). In two case studies, Wakely and Dakin demonstrate the value of a resulting policy scheme and work flows for assessment of access to personal information from the Wellcome Library collections. Although a certain level of subjectivity remains present and risks of censorship increase, Wakely and Dakin conclude that high levels of subjectivity are diminished by applying the developed flowcharts (Wakely & Dakin, 2015, p 60). The experiences in the Wellcome Library are important as example practice for dealing with sensitive materials in a (online) library environment.

For museums, however, other factors come into play. When it comes to sensitivity, it is always a matter of defining what is perceived as sensitive to whom and in what context. Audiences or spectators, those doing the looking at the material and the processes involved, are vital. And at the same time they are the most difficult to grasp or predict.

Current exhibition ethics involve value judgements and considerations about awareness of feelings in public groups.[11] This involves issues around content, human remains, objects of sacred significance, looted material and the interpretations and presentation of objects. In the case of clinical photographs this might involve questions such as: Which photographs should we display?; Are we allowed to display photographs which show nude or clearly discomforted patients?; How do we deal with patient voices?; Do we tell visitors the history behind our collections?; and, Do we instigate dialogue around patient privacy and patient representations?

A museum environment frames stories and narratives in many ways. To a certain extent, museum narratives are part of the processes of remembering. The staging of clinical photographs in exhibition spaces inside museum buildings works in a different way than displaying such images online, for example. Apart from the self-evident selection of the images, enlargements (size), location and interaction with objects, text, sound or moving images are only some of the determinants for narrative building and framing.[12] Museums can thus create and activate memories of patient histories of a particular disease, of an institution, location or country, for example. Clinical photographs can be objects par excellence in recounting disease stories. But the museum, or the curator, can choose to ‘use’ the patient’s photographs to tell this story or that, to stage a patient as sufferer or survivor, as victim or as example of medicine’s great victory over disease. As Susan Sontag tells us in her book Regarding the Pain of Others: ‘All photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions’ and ‘The photographer’s intentions do not determine the meaning of the photograph, which will have its own career, blown by the whims and loyalties of the diverse communities that have use for it’ (Sontag, 2003). As Elizabeth Edwards argued, through their collection practices, photographs have a ‘life as social entities, becoming historically specific statements and cultural objects in their own right’ (Edwards & Mead, eds, 2015).

Museums can offer things that other places cannot. I would argue that a museum can be a platform for debate to serve public interests and communities and at the same time stage the images in such a way as to respect the rights of past, deceased patients. Concern for privacy is only one historically rooted issue for exhibiting, but what about the social responsibilities of museums? Museums harbour ‘memory workers’ that can ‘kindle social aspirations like empathy, identification, cross-cultural dialogue, to recognize multiple perspectives, or to catalyse action’, as stated in Curating difficult knowledge (Lehrer, Milton & Patterson, 2011). As far as medical history is concerned, museums may thus reshape public consciousness of medical practices then and now, urging us to rethink the position of (marginalised) patients, children, women, workers, prostitutes, colonial subjects, or any other ‘victimised’ community in society. But the new critical museology moves even further, calling for democratisation of access and authority (Lehrer, Milton & Patterson, 2011, p 5). Innovative curatorial practices around ‘difficult knowledge’ of violence and oppression involve ways of representing the interests and voices of communities in museums or for audiences to consider the ethics of representation and exhibition itself. Although clinical photographs may not fit the category ‘difficult knowledge’ perfectly, these innovative curatorial practices could form a starting point for new paths of curating these collections.

The power of photographs is their performative ‘work’ in museums. However, as Elizabeth Edwards and Matt Mead have argued, photographs ‘rank low in the hierarchies of museum objects’ and are often marginalised and undervalued in museum practice (Edwards & Mead, 2013). They show how, for colonial photography, its invisibility in museums was both a symptom of and metaphor for the ‘invisibility’ of the colonial past (Edwards & Mead, 2013, p 33). Suzannah Biernoff similarly discusses in a convincing way the performative power photographs can play (Biernoff, 2011). She studied graphic case photographs from First World War archives which were used in a computer game called BioShock and showed how ‘the photographs question the limits and propriety of spectatorship’ (Biernoff, 2011, p 326). In another article in Photographies, Biernoff wonders whether there are ‘ethical considerations raised by their [the photographs’] redeployment or appropriation within the context of art and entertainment, education and academic research?’ (Biernoff, 2012). A museum ideally moves beyond these realms and can act as a ‘moral agent’, as stated in the preface to the 2011 Routledge Companion to Museum Ethics: ‘Museum ethics is more than the personal and professional ethics of individuals and concerns the capacity of institutions to generate self-reflective and activist practice’ (Marstine, 2011, xxiii).

Yet the performative work done by photographs in museums is not easy to control. How could I as a curator stage clinical photographs in such a way as not to fall into the semiotic energy and power relation of these specific images? The difficulty for curating lies in dealing with the ‘realist insistence of the photographic image’ and to stage them in an exhibition narrative – a ‘controlled reading’ – where the photographs become integral to knowledge making (Edwards & Mead, 2013, p 33). The relationship between exposing and exhibiting clinical photographs is my main concern here. Historian Jan Nicholas in her paper on the study of freakery asks herself the question whether historians have an ethical duty to the dead and if she should protect her historical subjects against voyeuristic gazes or tell their story instead (Nicholas, 2014). She eventually opts for a middle way, allowing for a ‘respectful politics of looking – and of framing ourselves as modest witnesses’ (Nicholas, 2014, p 155). Similar to scholars, curators of clinical collections, I argue, would have to take comparable complexities into account. Clinical images can be made more integral to the narrative in medical or science museums, to take the layered meanings of clinical photographs as personal yet institutional documents into account and also reflect on witnessing practices in museums. For most of us become patients at some point in time.

We currently live in a time of growing interest in and worries about privacy. A 2015 Science special entitled ‘The end of privacy’ marks our concerns with the use or abuse of personal data. In this context, discussions on curating clinical photographic collections can enrich ongoing debates, museological practices and visitors alike. Clinical imagery and concerns about data protection seen as mutual historically situated issues can deepen our understanding of privacy protection.

But there is no universally applicable answer or solution for how to display clinical imagery. I have argued that an awareness of the material as complex and sensitive but similarly worthwhile of exhibiting can go together. Following current museum ethics, informed decisions about display in exhibitions that shun sensationalism, morbid curiosity, or commodification of clinical photographs are important. Curating means to deal with the ‘burden’ of care and obligations to share as well. Considering the clinical photographic collections in the Boerhaave Museum, I decided not to keep the images away from audiences,[13] but to take ethical and privacy issues into consideration. This has led, for example, to the Museum Boerhaave not displaying some very explicit clinical photographs of naked children in vulnerable positions in our online database. For those interested, the images are still available for research or other uses. A similar attentiveness applies to this very (online) article, and the thought given to the kinds of images to show.

Ethical questions bring arguments, good and bad, to the surface. There are no moral absolutes when it comes to the exhibition of sensitive materials. Neither does curating end with display in a museum or gallery; care for the images is a continuous process, continuously asking for reflection. Clinical or other medical images can lead their own virtual lives. Also, some patients indicate when asked that they do want their material to be open for others to see and learn from, but that would fit within our current frame of ‘informed consent’ (Onion, 2014).

Depending on their mission, each institution may choose different paths of public access to historical patient photography. Historian Michael Sappol of the US National Library of Medicine contentiously argued for open online access to historical medical imagery without regulation: ‘We are stewards of these historical materials. […] They don’t belong to us. They belong to everybody. […] I would not like to act on behalf of the subjects and arrogate to myself the job of being some kind of policeman of “who can view”’ (Onion, 2014). This position represents one extreme end of the spectrum. There are many different solutions between free access, partial access or limited access. As suggested in the approach by the Wellcome Library, these definitions in turn involve interpretive decisions informed by ethical principles.

Museums and curators are creative in dealing with ‘difficult’ knowledge. New ways of memory curation and activation are explored in a search for audience participation. The participatory process itself can even become part of the exhibition experience. In the case of clinical photographs this could imply including a search for family or relatives, or results of focus group discussions with patients suffering from similar conditions. A wonderful example in this respect is the project The Children of Craig-y-nos, a public and oral history project of life in a Welsh tuberculosis sanatorium (1922–1959) by Ann Shaw and Carole Reeves (Shaw & Reeves, 2009). This project included three photographic exhibitions of images collected by ex-patients and staff. Another example where patient involvement dominated was the exhibition Rather Seen Than Looked At in the Boerhaave Museum in 2007–2008, which displayed large photographic images of patients with skin diseases who ‘looked back’ at the spectator (see image below).[14] The patients in the photographic portraits granted permission to look at them as an audience, not as a voyeur in the street turning one’s head inadvertently, but straight into their eyes, concentrated. The colour photographs were enlarged and printed together with written personal life stories beneath the images. This combination resulted in close and personal encounters between the public and the represented patient.

A recent and very appropriate exhibition in the context of ethical considerations around historical patient photography is the 2015 exhibition The Kiss of Light: Nursing and Light Therapy in 20th-century Britain at the Florence Nightingale Museum in London. As the director of the Museum explained, staff struggled with the public display of patient photographs, in this case mostly photographs of children:[15] ‘To our modern eyes, the exposure of children’s skin to intense ultra-violet light makes us feel uneasy, as does the photographs of children often wearing little else apart from large goggles to protect their eyes from the rays. The exhibition curator and the museum team have endeavoured to display these images in a sensitive but thought-provoking way.’[16] Such a thoughtful consideration of the sensitivity of the material on display could, in my view, serve as an example of best practice for dealing with historical patient photography. The awareness of the ethical issues involved bear witness to a present day professional self-reflexive attitude and sensitivity to the public in exhibition work.

Museums can matter. Exhibiting or disclosing medical or, more particular, clinical photographs in public spaces may offer spectators an opportunity to bear witness to traumatic, painful or difficult histories. For curators this is a complex and affective challenge, but one that may enrich engagement with medical heritage, histories and understanding of human suffering. If not for giving others opportunities to contemplate, learn, share, remember or witness past suffering and cures, then to involve all communities and audiences in what it takes to deal with glass patients like girl P.

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text