Uncovering the secrets of Canadian Pacific

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010

Abstract

Canadian Pacific is known as being the oldest and fastest surviving Merchant Navy class locomotive in preservation, but she hides a secret: she was built in 1941 at Eastleigh Works, Hampshire, where about half of the workforce were female. While she now stands as a testament of the work of these female engineers who were employed on the railway during the Second World War, their achievements wouldn’t have been possible without the long history of women working on the railway as early as 1840. The First World War opened up the opportunities available to women on the railway, throwing them into areas previously only occupied by men. Women fought prejudice to show that they were capable workers in the fields that were opened to them, but it all came to an end in peacetime when women were forced back into ‘female’ jobs. The Second World War again brought about change, with women being employed in more roles than ever before.

Keywords

Canadian Pacific, Eastleigh Works, engineering, First World War, Hampshire, Locomotive, London and South Western Railway, Merchant Navy, Railway, Railwaywomen, Second World War, Southern Railway, Women

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Railways have long been the domain of men. There is an understanding among historians that women only trespassed into this domain in the early twentieth century with the onset of war. While this may be true to a point, women have had a history of working on the railways from as early as 1850. Certainly, the relationship between women and railways changed dramatically with the onset of the First World War: from 1914 women started to invade a predominately male industry, taking up what had previously been male-only roles. The influx of women onto the railways was frowned upon by railwaymen, but this early pioneering in the railway by women laid the foundation for an even greater contribution during the Second World War which saw women working on the railways in far greater numbers and taking up a greater variety of roles. One job which has long been disputed is the role of women in the construction of locomotives. Their role in the railway workshops has been downplayed in the historical literature, but a project centring on one locomotive is hoping to change all that.[1]

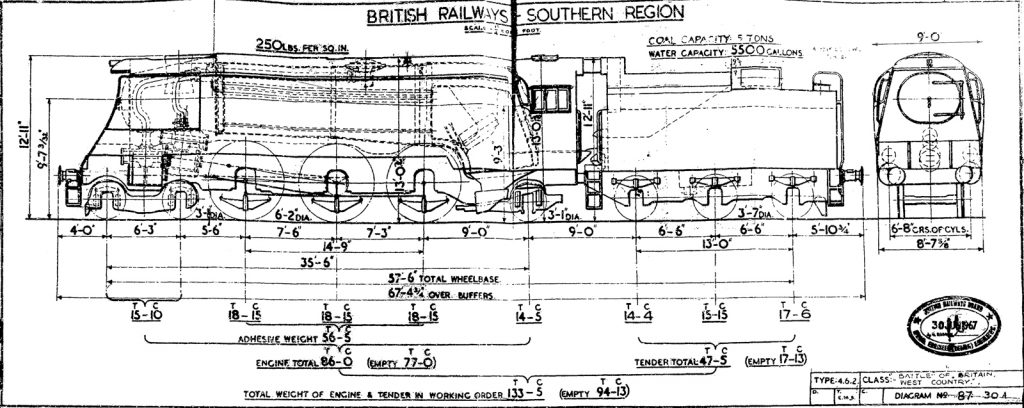

Canadian Pacific is a Merchant Navy class locomotive built in Eastleigh Works with the aid of a female workforce in 1941 (see Figure 1). It was the fifth engine of the class to be built in Eastleigh Works and entered traffic in 1942. It was named on 27 March 1942 after the Canadian Pacific Shipping Line, which travelled from Canada to Liverpool and Southampton. It should be noted that locomotives received periodic overhauls throughout their life and on occasion the replacement of large parts was necessary. For example, Canadian Pacific and the rest of the Merchant Navy locomotives[2] were redesigned in the 1950s to R G Jarvis’ conventional standard. This meant the removal of a number of parts including the air-smoothed casing, which gave it a rectangular look. Although Canadian Pacific has been re-built and overhauled twice more for preservation purposes, we are lucky to have a substantial proportion of the original 1941 locomotive still surviving. Canadian Pacific’s frames are original and have had minimal work done to them. A number of the ‘smaller’ items such as the lubricators and cab lights, etc. are also original, as are the wheels. Canadian Pacific does have an original 1941 boiler although it is not the one that she was fitted with. This does not diminish the significance of the locomotive. Through its survival and preservation, its identity stands as a powerful symbol of the work carried out by women in the Second World War.

In order to better understand how women came to be involved in the construction of Canadian Pacific in 1941, we must understand the longer history of women on the railways, which is discussed below.

The early railways

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010/002The railway has always been viewed as a very male-centred industry. Today women play a more active role in the running of the railway but for many the railway in the past was filled with men, and it was perceived at the time as an environment where women did not belong. In many ways this misconception is understandable, and surviving photographs reinforce the idea.

However, these images only tell one side of the story. Many people are unaware that women worked on the railways as early as 1850. In the 1851 census, for example, there are fifty railwaywomen cited, and by 1901 this had grown to 1,633 railwaywomen (Wojtczak, 2005:5). About a third of these women would have worked in the hotel industry as cooks, chambermaids, kitchen assistants, cleaners, laundresses and waitresses, with the highest grades in this area being housekeeper and tea room manageress. It seems surprising nowadays that a woman could be described as a ‘railwaywoman’ while working in the hotel industry, but it is important to note that at this time the railway owned a great deal of infrastructure and real-estate including hotels and taverns that people frequented on their journeys. Many railways also owned docks (for example, London and South Western Railway owned Southampton Docks), and even steam ships: the steam ships travelling to Jersey and Guernsey from Southampton Docks were owned by London and South Western Railway.

The hotel industry was not the only work available to women on the railway in 1901 but it is certainly true that other roles available were very limited. The highest rank a woman could achieve on the railways themselves was that of an Inspectress. This job consisted of checking that ladies’ accommodation was up to standard and involved managing female staff (women never managed men on the railway). Women could also be crossing keepers. This job was usually offered to a disabled railwayman, since it was light work that could easily be performed by a person with limited mobility and strength and it could be offered to a woman on a man’s refusal or absence. This job was sought after as it came with a house, and in many cases it ended up being passed between female family members. These crossings were small with little traffic and so were deemed easy enough for women to manage. Those women who took up the position were paid a lower rate of pay compared to male crossing keepers and were expected to work the same hours; however, many women enjoyed the job as it allowed them the flexibility to raise a family while working. Another job available to women was carriage cleaning. Again, this was offered with some restrictions, with women only allowed to clean carriages in the station as the yard was considered the domain of men.

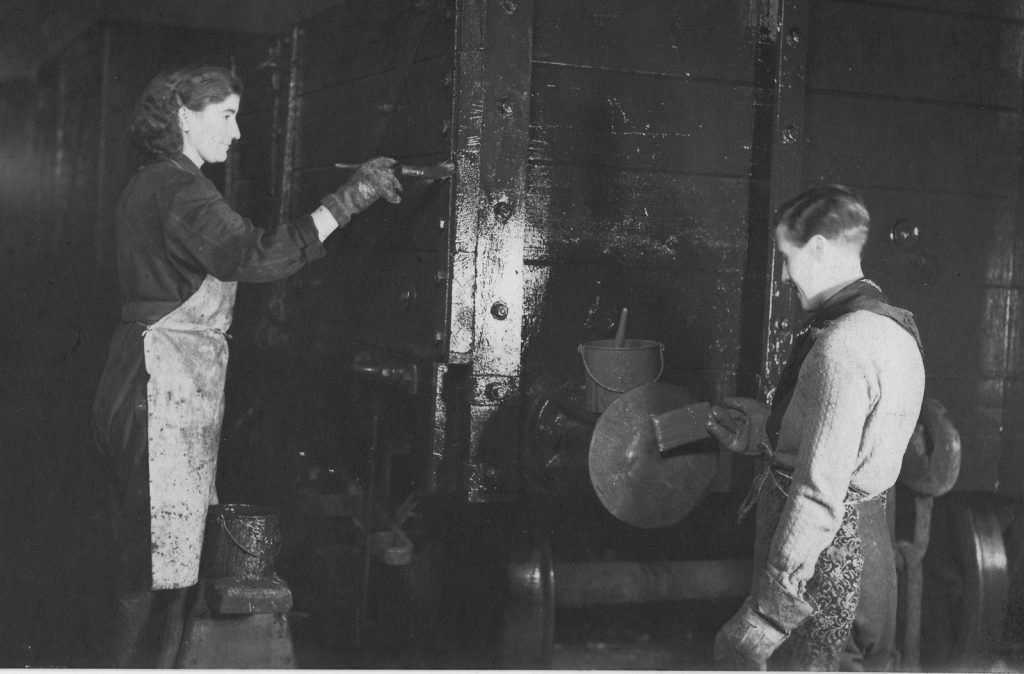

Women were employed as early as 1840 in the railway workshops such as Nine Elms in London, but there were still restrictions for women. In the railway workshops women were employed in what might be considered typically female roles: upholstering, painting, cleaning and catering, to name a few (see Figure 4). London and South Western Railway employed women actively and had a policy of hiring women who were widowed by accidents on the railway. They were always in female roles but the work did enable them to support themselves and their dependents. This is a very different view of the railway from the male-centred and harsh world that has been portrayed in books such as Bonavia’s The History of the Southern Railway (1987).

Change is coming: the First World War

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010/003The railways underwent a dramatic change with the start of the First World War in 1914. Large numbers of men left the railways to join the forces, even though railway work was a protected profession. This threatened the movement of troops and supplies by London and South Western Railway which serviced the south of England. The government decided to step in and take charge of the situation, pushing aside the railway companies and taking control through the Railway Executive Committee. Precedent had already been set in industries such as manufacturing where women had replaced men and the government proposed that women should replace those railwaymen that had left to fight. Unfortunately, this didn’t go down well with the unions or the railwaymen left behind. The railwaymen had three broad objections to women working on the railways, particularly in male grades (Railway Review 1915, National Union of Railwaymen). The first objection was that women were both mentally and physically incapable of railway work. Physically women were not built to cope with the physical nature of the work, the men argued, and mentally they were supposedly too feeble minded to comprehend the complexity of railway work. Women quickly proved they were both physically and mentally capable on the railways. The second objection was economic: railwaymen had fought long and hard for a higher rate of pay, their jobs was extremely dangerous, with a high accident rate amongst railway workers (although not the highest accident rate in the country, which was reserved for coal-miners). An example of the potential danger of the environment was the policy of placing first-class passengers at the back of trains, as far away from the locomotive as physically possible. This was in the hope that if the locomotive exploded the first-class passengers would survive. Railwaymen’s pay reflected this dangerous work, while women were paid a lower rate of pay than their male colleagues. Railwaymen were worried that if women worked in male grades and proved they could do the job just as well as them, the men’s rate of pay would decrease. It was thought that railway companies would try any way to pay the men less for the job and consequently women were seen as the enemy. The third objection speaks to the railway psyche: when you joined the railway you didn’t just join a profession, you became part of a family and that family looked after you. The railwaymen who did not leave to fight were worried that colleagues who had joined the forces would have no jobs to return to once the war had ended because women now occupied them. Therefore, it was agreed by the National Union of Railwaymen and the Railway Executive Committee that on the return of a railwayman, the woman working in his position would be fired automatically. The agreement also stated that women would receive no war bonus and no uniform (National Union of Railwaymen, Meeting Minutes April 1915). For many of the men, women working on the railways as part of the war effort were not really part of the railway, just a nuisance to be tolerated.

Once these agreements had been made in 1915, women started entering the railway, taking up both female and male roles. Jobs which women had held before the war started to change. For example, carriage cleaners before the war were only allowed to clean carriages on the platforms. Now women were now allowed into the yard, an area that had previously been an entirely male domain. Moreover, women were not only cleaning carriages, they were now assigned to cleaning locomotives. However, no uniform was provided, and women were expected to clean locomotives and carriages in their ordinary clothing, which consisted of floor length skirts, and dresses and corsets. A number of carriage cleaners passed out on the top of the carriages and locomotives because of their clothing restriction but this did not seem to worry the railway companies. It took a group of carriage cleaners at Wimbledon Park Depot (which was owned by London and South Western Railway) to tackle the clothing issue by donning men’s breeches. The newspapers referred to them as ‘the ladies’ maids to locomotives’ and ‘our heroines in overalls’ and after this, the railway company conceded that the women could wear overalls to complete their work. It may seem surprising that women had to fight for their right to wear appropriate clothing for the profession rather than it being provided, however, this reflects the prevailing view that women were a temporary nuisance on the railway, even if their roles had expanded due to the war. Railway historian Helena Wojtczak notes that, by October 1916, 2,173 women were employed as carriage cleaners. The first loco cleaners were hired in March 1916 and in six months 587 had been recruited; in two years there were over three thousand (Wojtczak, 2005, p 52–53). Thus, female carriage and locomotive cleaners in the First World War played a huge part in the running and maintenance of the railways stock.

Other new jobs were becoming available to women because of the war. Women were now allowed to work in male grades performing such jobs as ticket collector, guard, and goods porter. Just like carriage cleaners, women were not provided a uniform in these roles (it took until 1956 for the railways to make an item of female clothing). For the first-time women were allowed to work as police officers in what would become the British Transport Police. Female police officers were not allowed to arrest or even caution a man. On some railways (for example the Caledonian Railway) female police officers had no power of arrest and in Piccadilly Circus they only dealt with women.

Despite the restrictions and reluctance to accept women workers, railwaywomen in the First World War quickly proved that they were capable of all types of railway work. However, many were not treated well. In Eastleigh Works women were obliged to sign an undertaking not to join any society or association. The companies claimed that this was to prevent their employees becoming suffragettes but managers later claimed that it also encompassed unions (Wojtczak, 2005, p 80). Women who signed this agreement had no one to represent them and it meant that the railway companies had total control over their working lives. For example, female clerks worked in all-female offices separated from the rest of the workforce in order to stop fraternisation – the assumption being fraternisation was entirely the woman’s fault.[3] Female clerks were also dismissed on marriage, although this practice was not restricted to the railway. Women were usually dismissed on marriage in other industries well into the 1960s.

‘By December 1916 there were over 46,000 women working in 135 grades, of whom more than 34,000 were performing work that had previously been considered only suitable for men’ (Wojtczak, 2005, p 91, Eastleigh Appointments book 1916–1923). With the end of the First World War in 1918, the railway returned to its pre-1914 structure. Railwaywomen were quickly dismissed from the railway and many women faced hostility if they tried to stay. Those women that did stay were forced back into female roles. It was as if women had never held male grades on the railway and all the achievements that women had made were lost until the Second World War (see Southern Railway census of staff 1931 for roles held before WWII[4]).

Women are needed again: the Second World War

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010/004In the Second World War the railway didn’t cease to function as it had at the beginning of the First World War. The government took over the railways quickly and women were employed as soon as railwayman started to leave to fight. 98,000 railwaymen left to join the forces and by 1943 there were 88,464 women working on the railways. This was made possible because of the groundwork made by women in the First World War who had fought against prejudice and showed that women could complete jobs previously considered only fit for men. During the Second World War a wider range of jobs became available for women including previously male-only roles such as ticket collector, guard and porter (Mid Hants Railway Staff lists; Wyeth, 2017). In addition, some of the roles that had been available in the First World War started to expand: female police officers were now able to arrest women – a small but significant step. For the first time women were employed in track maintenance and by 1944 over two thousand women were employed in this role furthering the challenge that women in the First World War had made to the idea that women were mentally and physically incapable of the more physical types of railway work. Women could also now be wheel tappers, fog signallers, perform shunter duties, be number takers, operate cranes and be gas fitters, all roles unavailable to women before the Second World War. For the first time, women were trained in signalling, and to the railway company’s surprise they excelled at the role (Mid Hants Railway staff photograph, 1946). In fact, women turned out to be so good at signalling that the Southern Railway built three colleges to train women for the role. It took between 2-4 months to train a signalwoman and up to six months to train a signalman. The railways were beginning to realise that women could not only match, but surpass railwaymen when it came to certain roles.

One area that saw an increase in female workers in the early 1940s was in the railway workshops such as Eastleigh Works in Hampshire. Women had long been employed in the railway workshops but largely in female roles as discussed above. Eastleigh Works was built in 1891 when the London and South Western Railway needed to find a more suitable location than Nine Elms in London for their railway works (Robertson, 1992). Eastleigh was considered a better location as it ‘was a green field site lying in the shadow of its more important neighbour, Bishopstoke’ (Robertson, 1992:9). The new location would allow the railway works more room for expansion, which was not possible at Nine Elms. From 1891, Eastleigh became the home of the London and South Western Railway Carriage and Wagon Workshops and 1910 saw the move of the Locomotive Workshops to Eastleigh too (Legg, 2012). In 1923, London and South Western Railway became the Southern Railway and the workshops carried on being used under that title (Maggs, 2012, p 31–2).

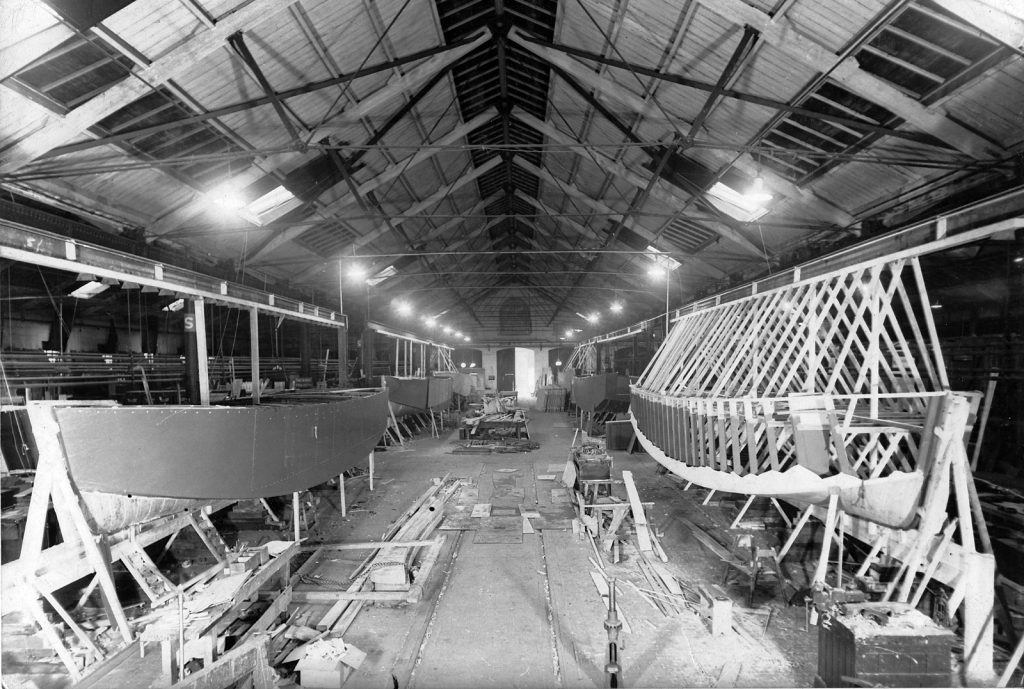

During the Second World War, Eastleigh Works was the main Locomotive, and Carriage and Wagon Works for the Southern Railway, but it was also used to build tailplanes for Horsa gliders[5] (see Figure 5), ammunition, Matilda tanks, bomb trolleys and landing craft (see Figure 6) as part of the war effort (Wragg, 2006, p 121).

In most areas of the railway, men and women were separated but this was not the case in Eastleigh because the women employed were family members of railwaymen (see Figure 7). Many railwaymen pressurised their female family members to work for the railway during the war to ensure that their daughters and wives were not conscripted for war work elsewhere in the country and families could keep an eye on them. But working together created its own tensions as fraternisation with these women was extremely frowned upon. In fact, levels of fraternisation at Eastleigh Works were the lowest compared to anywhere else on the railway, although there were instances of it still occurring (Canadian Pacific Project Oral History). In many jobs away from the Works, men and women were separated to make sure fraternisation didn’t occur but there were some other roles where men and women had to work in close proximity. One of these roles was signalling and, in many cases male signal workers had never worked with women and were uneasy with this new workforce (Railway Review 21 May 1915, Wojtczak, 2005, p 180).

A secret uncovered: Canadian Pacific

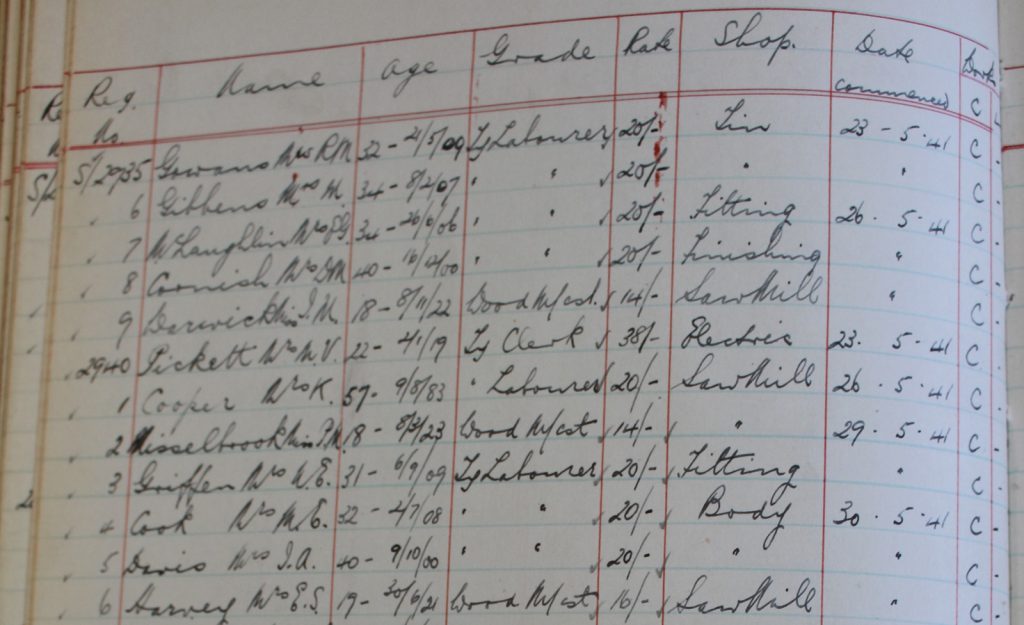

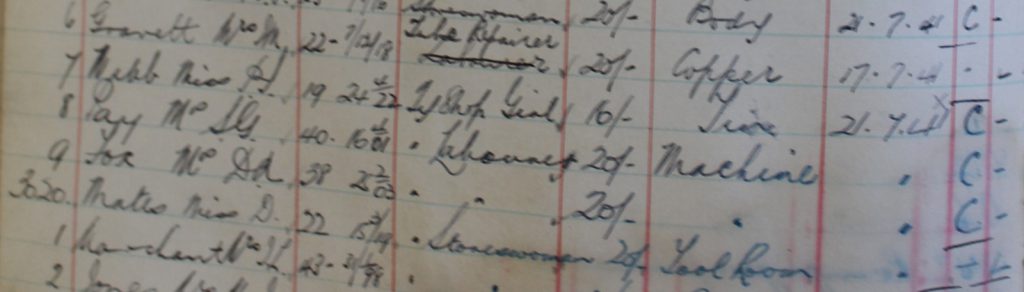

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010/005Eastleigh Works in the Second World War employed women who worked on the carriages, wagons and locomotives (Boocock and Stanton, 2006:51; Eastleigh Works Appointments book 1936–1943; Asprey, 2017). Women now worked in the dining hall, paint shop, sawmill, body shop, forge, erecting shop, and the machine shop (Eastleigh Works Appointments book 1936–1943). The extent of women’s roles on the railways in the Second World War can be seen in the films created by the Southern Railway Film Unit. Good examples of this are Ladies Only (1942) and Bundles for Berlin (1943).[6]

One area in the Works where women took over to a very great extent was the machine shop, and in fact by 1940 the only railwayman left in the machine shop was the Assistant Machine Shop Foreman, Mr Asprey (Asprey, 2017). The women performed complex tasks using hand operated machinery such as capstan mills and lathes. Many of the jobs would have been making replacements parts for carriages and locomotives, stays and other parts needed to repair damaged stock.

In 1938 Chief Mechanical Engineer, Oliver Bulleid (see Figure 8) decided to build ten new locomotives for the Southern Railway (Haresnape, 1985, p 18). Thus, the women employed in Eastleigh Works from 1939 helped in building the first ten Merchant Navy class locomotives, including Canadian Pacific. These were advanced steam locomotives designed with novel features such as chain-driven valve gears, Bulleid-Firth-Brown wheels, electric lighting, air-smoothed casing, oil baths and an all steel-welded boiler (see Figure 9).

It is in some ways extraordinary that ten new locomotives were allowed to be built during the Second World War when so much effort was focused on producing arms, but the Southern Railway managed to get the designs past the Board of Trade Inspectors (Mannion, 1988:8). A number of the features were sold as making the maintenance of these locomotives easier, therefore reducing costs. This was deemed important as the Southern Railway was ‘the most financially successful of the four railway companies’ (Mannion, 1988:6) and these new locomotives replaced the Southern Railways old and tired running stock. During the Second World War the Southern Railway ran ‘30,890 troop trains, carried 9,367,886 troops, ran 1,127 PoW trains and carried 582,005 PoWs’ (Wragg, 2006:109; Wyeth, 2017; Bell, 2017). It also handled 31,135 special trains (Polley, 1994:93). The Southern Railway was also involved in the evacuation of children from Medway towns running 54 trains and running 172 trains from Portsmouth, Southampton and Gosport (Bonavia, 1987:165; Curdridge Parish Council; Ashford Hill).

While there is an acceptance among historians that women did help on the railway during Second World War, in many cases the extent of their roles is played down (see for example Bernard Darwin’s book War on the Line, originally published 1946). This is especially true for women’s role in the workshops. The misconception that women were not involved heavily in the railway workshops has made it even harder for people to accept that women were involved in the construction of a steam locomotive. Books such as Darwin’s reflect the attitudes of the time and many later authors cite secondary sources such as this rather than looking at the original archives. This perpetuates the myth that women were not involved in the construction of locomotives and thus the very male centred culture within railways and the writing of their history can still be seen today.[7]

Research conducted as part of the Canadian Pacific Project looked more closely at women’s roles in the Eastleigh Workshops during the Second World War. From the appointments books and testimony[8], we can safely say that women were actively involved in the maintenance and building of steam locomotives (Figure 10 and 11; Asprey, 2017).

During the time when Canadian Pacific and the other Merchant Navy class locomotives were being built large numbers of women were working within Eastleigh Works, up to 1,500 at any one time. Moreover, the records show that women were working within crucial areas of the Works that would have been heavily involved in the construction of Canadian Pacific. These included the machine shop, wheel shop, fitting shop, sawmill, offices, wagon shop, paint shop, lining room, finishing shop, brake shop, copper shop, electric shop and brick shop in Eastleigh Works, all of which contributed to the construction of Canadian Pacific and the other Merchant Navy class locomotives (Figures 10 and 11). The involvement of these women in the building of locomotives is an important and under-appreciated part of Canadian Pacific’s story. Nowadays, the Merchant Navy locomotives are remembered largely for their performance and design, but the involvement of women in their construction is absent from their history. Canadian Pacific is one of the first ten Merchant Navy locomotives built in Eastleigh Works and the oldest surviving member of the class. But it is not just important for its age: on 15 May 1965, Canadian Pacific travelled 105 mph down Winchester bank (Wilson, 2014). Thus, it is both the oldest and fastest surviving Merchant Navy locomotive in preservation, but more than that it is a testament to the women who were involved in the construction of locomotives in the Second World War and a true example of female engineering. It should make the women involved in its construction proud.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/181010/006Canadian Pacific stands as a powerful symbol of the work carried out by women in the Second World War. However, without the struggles of women on the early railways and the major changes carved out by women in the First World War this would not have been possible. Women worked on the railways as early as 1850 but real change occurred with the onset of the First World War. Women entered the railways in large numbers at this time, taking on jobs never before performed by women. It was not an easy task as railwaymen had many objections to female workers. But their perseverance and hard work challenged perceptions of women being both mentally and physically incapable of railway work. Even if, at the end of the First World War, women were forced back into female roles, their pioneering spirit paved the way for women in the Second World War to perform more physically demanding jobs, opening up more jobs even in the traditionally male preserve of the railway workshop. All this led to the ultimate achievement for women – to be involved in the building of locomotives, of which Canadian Pacific is a shining example.

Canadian Pacific, although in its third overhaul in preservation and much changed from its original design in 1941, is still a powerful symbol of the work carried out by women during the Second World War. We are lucky that some of the original locomotive survives and although the current work to restore her will further reduce its ‘originality’, it is an exemplar and surviving symbol of the work of women on the railways during this time. Eleven of the Merchant Navy class survive today, with 35029 Ellerman Lines preserved and sectioned in the National Railway Museum at York. However, Ellerman Lines was not built until 1949 when Eastleigh Works had lost the majority of its female staff, particularly those that had held male roles.

Canadian Pacific is a testament to the women who were engaged in skilled work in the railway engineering workshops during the Second World War. Historians have not given this contribution to the war effort the recognition it deserves and in many cases they gloss over the extent of women’s involvement with the railways. The locomotive is remembered for its performance and design rather than it being an example of female engineering. In fact, Canadian Pacific is also a tribute to the female workers that built the locomotive.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my very great appreciation to the Mid Hants Railway who have allowed me as part of the Canadian Pacific Project to research this topic. I also wish to acknowledge the help provided by the Heritage Lottery Fund who have generously given the project £895,000 to help us restore Canadian Pacific to working condition.

www.watercressline.co.uk/canpac

Tags

Footnotes

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text

Back to text