Photographic plates and spirit fakes: remembering Harry Price’s investigation of William Hope’s spirit photography at its centenary

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221707

Abstract

During the opening decades of the twentieth century, William Hope was a well-respected medium amongst the spiritualist community in Britain, with positive endorsements from major scientific figures such as the chemist William Crookes and the author and physician Arthur Conan Doyle. Hope was often seen as one of the few mediums to be able to produce authentic spirit photographs. However, all that changed in late February 1922 when the magician-turned-psychical researcher Harry Price claimed to have caught Hope cheating during a sitting, by discovering that he was swapping blank photographic plates for ones with supposed spirit ‘extras’ already on them. Hope was publicly exposed as a fraud, and what ensued was a major debate between believers and sceptics over the legitimacy of the medium’s alleged spirit photography. The Hope-Price affair became a media sensation in the months that ensued, with a series of articles about the investigation and its aftermath appearing in the major spiritualist magazine Light. While much has been written about the Hope-Price affair as a key example of fake mediumship, most of these accounts tend to prioritise the sceptic’s perspective, with little attention paid to spiritualist responses. This paper will provide a more balanced narrative, focusing on one of the main criticisms of Hope’s defenders at the time: the credibility of Price’s testimony. Because Price actively misled Hope and his associates in a bid to catch the medium cheating, his trustworthiness as an objective observer and investigator of extraordinary phenomena was questioned. Key to this analysis is the essential role material evidence played in this case, with particular emphasis on the photographic technologies and processes used.

Keywords

Harry Price, mediums and psychics, mediumship, psychical research, scientific testimony, spirit photography, spiritualism, William Hope

Introduction: personal testimonies and material evidence

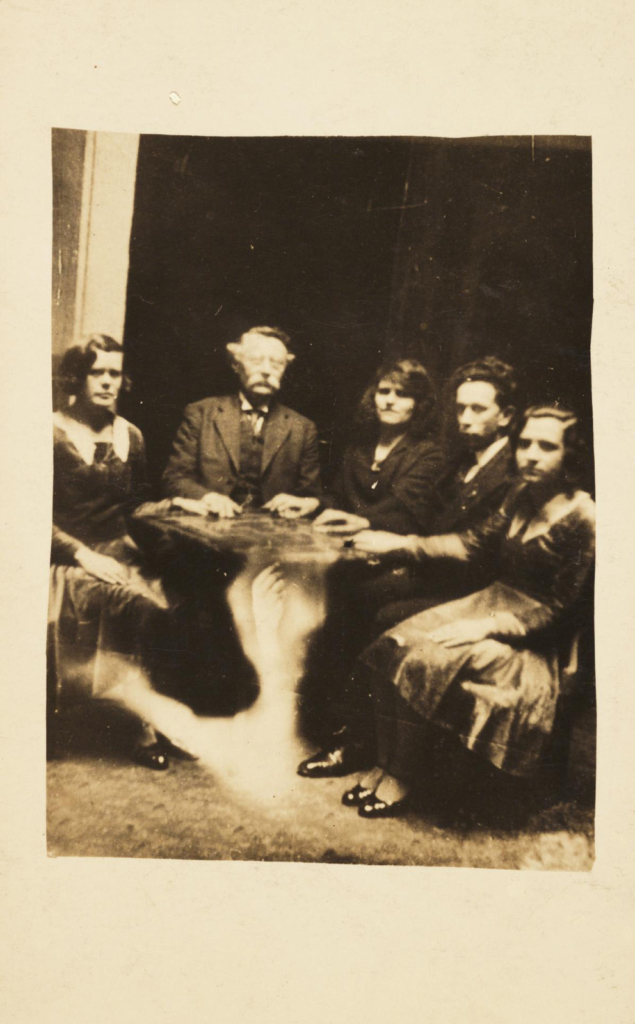

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221707/002Tucked away in the photographic collections at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford is a small photobook containing images produced around 1920 by the professed British medium William Hope. This unassuming collection of photographs looks like any number of spirit photo-albums created between the late Victorian period and the early twentieth century. It includes examples of ghostly hands moving tables during séances (see Figure 1), as well as portraits that contain spirit extras, such as a photograph of the Welsh medium Joe Thomas and an unknown female apparition (see Figure 2). Taken together, the photo-album provides an illustrative vignette of spiritualist life at the turn of the century.

The photo-album also provides an important entry point for remembering a key moment in the history of modern science’s relationship with spiritualism: Harry Price’s investigation of Hope’s mediumship in February 1922. In the canonical narrative told by Price, Hope was allegedly caught cheating when the secretly marked photographic plates supplied by Price were apparently swapped for different ones that likely contained ‘spirit extras’ already imprinted on them (Price, 1922, pp 271–283). While this story has come to be recognised by scholars such as Massimo Polidoro as a crucial example of scientific rationalism’s efforts to expose professional mediumship as nothing more than mere trickery and credulity, this paper wants to tell a different and more balanced story (Polidoro, 2011, pp 20–22).

A push toward a more wholistic understanding of the Hope-Price affair that explores both sides of the case highlights the kinds of biases that are inherent in the historiography. When it comes to ‘alternative sciences’ such as psychical research, only certain voices or perspectives tend to receive attention (Visvanathan, 2006, pp 164–169; Noakes, 2019, pp 8–9). By introducing the spiritualist’s viewpoint in this paper, we begin to see a very different portrait of spiritualism that avoids the risk of replicating the problematic divide between the supposed empowered and enlightened ‘scientific observer’ and the subjugated and superstitious ‘observed other’. Believers’ counter arguments to sceptics were methodical, detailed, and evidence-based. They were not the unsubstantiated ramblings of irrational and credulous people as it is so often portrayed in more pejorative accounts (for example, Polidoro, 2011, pp 20–22). Such a rethinking of spiritualism poses important questions about how the scholarship continues to tell the history of science through the perspective of the supposed ‘winners’, at the cost of constructing a skewed understanding of the past.

Although it is almost certainly the case that Hope was a fraud, and that the spirit photographs he produced were carefully crafted fakes, the investigation that Price led in the winter of 1922 is not as clear-cut as the historiography has suggested. In fact, the manner in which Price conducted his investigation at the time was heavily criticised by Hope’s defenders, especially among leading figures at the British College of Psychic Science (BCPS), most notably its President, James Hewat McKenzie. Through a careful reading of the original exposure, published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research in 1922, and the subsequent response by McKenzie in the pages of the spiritualist journal Light in November of that same year, the paper will aim to provide a critical reassessment of the Hope-Price affair that underscores the complicated nature of science and spiritualism’s historical relationship, and the limits of the evidence used for investigating these kinds of extraordinary phenomena.

The history of modern spiritualism is typically told through the personal testimonies of historical actors (believers and sceptics alike) who participated in spiritualist activities such as séances. This is understandable, given that the majority of the evidence collected at these events took the form of witness reports. However, like any kind of testimony, scientific or otherwise, there are always questions about the reliability of an account (Golan, 2014). It is for this reason that so much of the history of spiritualism and its engagement with science remains hotly contested. The ability to determine whether a witness report is credible has been a major focus of these deliberations. For some commentators, such as the late Victorian folklorist and anthropologist Edward Clodd, personal testimonies are a poor baseline for substantiating the reality of spirit and psychic phenomena because these accounts are far too subjective. Any definitive conclusion as to the legitimacy of spiritualism, which rests with a witness’s claims, is deeply questionable. Clodd devoted an entire volume to this argument, and he rejected every report attesting to the reality of spirit and psychic forces as dubious (Clodd, 1917).

Despite a version of Clodd’s argument being routinely applied to most cases where believers claim to confirm the reality of spiritualism, the same rules are rarely enforced when assessing the testimonies of sceptics and disbelievers. Far too often witnesses who have discredited spiritualism are taken for granted, with almost no critical reflection. The famous exposure of the medium Henry Slade by the biologist E Ray Lankester and the physician Horatio Bryan Donkin in 1876 is a good example to consider here. The only people present at the time of the exposure were Slade, Lankester and Donkin. Nevertheless, when the case went to court, after Lankester indicted Slade under the terms of the Vagrancy Act of 1824, the sceptic’s version of the story was accepted unreservedly as genuine by the presiding judge, while the believer’s account was denounced as credulous nonsense (Lester, 1995, pp 93–95). Slade was found guilty, but won his appeal on a technicality – there was an error in the original paperwork submitted to the court by Lankester. Before a retrial could be organised, Slade fled the UK never to return. Ever since the verdict, however, the story of Henry Slade’s legal battle continues to be told as a great victory for rationalism over credulous belief (Clodd, 1917, pp 49–51; Houdini, 1924, pp 79–116).

The logic that is employed in most of these cases is fairly similar. It is assumed that sceptical accounts are likely true because it is easier to accept them rather than the unlikely alternative, that mediums can actually produce incredible supernatural feats. This is by no means a suggestion that we should treat the reports of believers with any less level of critical awareness. Instead, for the sake of balance and integrity, we should apply the same standards to all kinds of testimonies, regardless of their perspective. After all, sceptics and disbelievers are just as prone to exaggeration and lies as their believer counterparts. Thus, as we arrive at the centenary of the Hope-Price affair, it seems an appropriate occasion to reconsider the credibility of Price’s testimony; even at the time of its publication in 1922, there were many critics who questioned its veracity.

The Hope-Price affair is an important case study for exploring a broader issue in the history of science about the different kinds of philosophical assumptions researchers use when interpreting the same sets of evidence. Even though the believers and sceptics in this story analysed the same materials, their interpretations and conclusions were remarkably different, and presented two divergent ‘realities’ of the investigation. This raises important questions about the standards of evidence in science, especially when dealing with extraordinary phenomena such as spirits and psychic forces. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s notion of ‘virtue epistemics’ is a particularly useful analytical tool for a study such as this one. It allows readers to unpick the ways in which these historical actors attempted to construct ideas of trust, authority, and reliability in relation to the key pieces of evidence surrounding the Hope-Price case. While this may seem at first glance to be little more than an interesting side story about the historical relationship between science and the occult, it does provide an important lesson for the historiography more broadly. The same kinds of concerns relating to the interpretation of testimony in the Hope-Price affair can be applied similarly to most studies in this history of science.

There is also another issue that can be addressed through a reconsideration of the Hope-Price affair: the role of material culture in spirit investigations. Spirit and psychic forces rarely leave material evidence that can be collected, with teleplasm and spirit photography being the main exceptions. This has further complicated the historiography, with most studies of the history of science and spiritualism tending to marginalise the material culture of spirit and psychic forces to the peripheries of their analyses (e.g., Oppenheim, 1985; Luckhurst, 2002; McCorristine, 2010; Josephson-Storm, 2017; and Raia, 2019).

Few major works have anchored their examinations using the objects that were employed during these investigations as their focal point. Simone Natale’s Supernatural Entertainments (2016) and Richard Noakes’ Physics and Psychics (2019) are notable exclusions to this trend. Even so, neither are object studies in the truest form. Spirit photographs, which regularly feature in both the primary and secondary literature, are also underused (e.g., Tucker, 2005, pp 98–103; and Kaplan, 2008). When they are discussed, the focus is squarely on the images and the superimposition techniques applied to them, with only fleeting attention paid to the whole set of photographic technologies and processes involved in their production (Tucker, 1997, pp 378–408; Kaplan, 2003, pp 18–27; Chéroux, 2005; Harvey, 2007; and Mitchell, 2014, pp 15–24). The foundation of Price’s supposed exposure of Hope rested with the objects used during his investigation. Thus, an analysis of the case that underuses these sources of evidence only provides a partial reconstruction of the affair. It is for these reasons that this paper will pay closer attention to the material elements of the Hope-Price case.

Despite representing one of the more significant cases that Price investigated during his long career as a psychical researcher, it is surprising that there have been only short discussions of the Hope investigation in the historiography. For example, the Hope-Price affair barely features in the major biographies of Price by Paul Tabori (1950, pp 65–79); Trevor Hall (1978, p 222), and Richard Morris (2006, pp 46–53). When the case is mentioned, the story is primarily told through the perspective of sceptics. The most sustained commentary by a believer was published in 1923, by the famed author of the Sherlock Holmes novels Arthur Conan Doyle, during the aftermath of the debate over Price’s findings in the spiritualist press (Doyle, 1923). Doyle became one of Price’s biggest critics in the years that followed, and tried on several occasions to derail Price’s budding career as a psychical researcher. Thus, as we approach the centenary of the Hope-Price affair, it is high time that we reflect more rigorously on the full details of this momentous case.

1. Retracing Harry Price’s investigation of William Hope

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221707/003Harry Price was relatively unknown amongst both the spiritualist and psychical research communities prior to his investigation of William Hope in 1922. Born in London in 1881, Price was educated at Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham College in New Cross, London (Morris, 2006, p 5). At the age of 15 he joined the Carleton Dramatic Society, where he began honing his skills as a performer and storyteller (Tabori, 1950, p 22). This training would later serve him well as a popular raconteur of occultism in the British media. However, it was a chance encounter with a faith healer named The Great Sequah in 1889 that led to Price’s lifelong interests in professional conjuring and spiritualism. The young Price was enthralled by Sequah’s mediumistic performance, and later recounted how he stood ‘open-mouthed at this display of credulity, self-deception, auto-suggestion… [and] beautiful showmanship’ (Tabori, 1950, p 21). Price rushed home to tell his parents all about the show, and soon after his father bought him a copy of Professor Hoffman’s Modern Magic (Lewis, 1876). During the closing decades of nineteenth century, Professor Hoffman’s Modern Magic was a staple read for would-be magicians and sceptics of spiritualism. The book would later become the first accession into the library of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, which Price founded in 1926 (Morris, 2006, pp 3–5). The encounter with Sequah, along with reading Professor Hoffman’s Modern Magic, marked the beginning of Price’s fascination and early career as a semi-professional conjurer and researcher of the occult. He joined the Magic Circle in 1922, the same year that he investigated Hope’s mediumship.

It was Price’s background as a professional conjurer that helped to establish him as an ideal investigator of Hope’s mediumship. His training in the art of deception meant that he was more likely able to catch how a fake medium produced their supposed extraordinary feats. Since the emergence of modern spiritualism with the Fox sisters in 1848, there had been a long line of magicians who sought to expose mediums as frauds. Take, for example, the Victorian conjurer John Nevil Maskelyne, who famously recreated the supposed psychic feats of the Davenports Brothers as a way of defaming their reputations as little more than skilled escapists (Steinmeyer, 2005, pp 95–96). Maskelyne is not an isolated example, and the renowned American magician Harry Houdini investigated countless mediums, discrediting all of them as charlatans and hustlers. Houdini even published a book about his investigations into spiritualism titled A Magician Among the Spirits (1924), which included a short summary of the Hope-Price affair as a classic example of a magician exposing fake mediumship (Houdini, 1924, pp 123–134).

Price’s investigation of Hope’s mediumship became a sensation in the spiritualist media, but to fully appreciate the complexity of the case, it is important to retrace the original narrative. The application of a ‘thick description’ is useful when retracing source materials such as the surviving records of the Hope-Price affair. Originally developed by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz as a way of examining the cultural web of ideas that create social paradigms, it is a useful technique for reconstructing the historical experiences of actors (Geertz, 1973, pp 25–26). Whether one is studying the present or the past, a researcher should describe in detail the experiences of his or her subjects, contextualise them, and expound on their social significance. Making sense of how ideas and actions are formed is an exercise in ‘operationalism’, and as Geertz explained, ‘if you want to understand what a science is, you should look in the first instance not at its theories or its findings… [but] at what the practitioners of it do’ (Geertz, 1973, p 5). To truly comprehend the historical ideas and activities connected to the Hope-Price affair in the early twentieth century, it is useful to produce a ‘thick description’ of the surviving accounts and tease out the key aspects for analysis (Geertz, 1973, pp 25–26).

We can also think about Price’s original testimony of his investigation into the professed mediumship of Hope as a kind of ethnographic account. Psychical research in this period was a kind of human science (Lamont, 2013, pp 201–204). Mediumship was seen by many investigators as being a human mental phenomenon, and studying professed psychics typically involved prolonged periods of direct engagement with a form of participant observation (McCorristine, 2010; Barfield, 1997, p 248). A classic example of this sort of deep and immersive investigation into mediumship is Oliver Lodge’s best-selling book, Raymond, or Life After Death (1916). The book recounts in detail the séances Lodge and his wife Mary held with the medium Gladys Osborne Leonard during the 1910s as they attempted to communicate with the spirit of their deceased son Raymond, who had died while serving as an officer in World War One. However, the connection between anthropology and spiritualism has a much longer history. Alfred Russel Wallace, for example, viewed spiritualism as an important subfield of the discipline in the 1860s (Sera-Shriar, 2020, pp 357–384). He too had extensive experience engaging first-hand with mediums at séances, which he recounted in his famous work, Miracles and Modern Spiritualism (1875).

The style of Price’s testimony also follows in a long tradition within the sciences of narrating the details of an investigation as a way of recreating the event for readers. Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer framed this practice as ‘virtual witnessing’ (Shaping and Schaffer, 1985, pp 55–65). Through this process of retelling the account through text, the investigation is legitimised. Price was acutely aware that he was employing this kind of rhetorical tool to substantiate the claims in his testimony. He was sure to include even the smallest details of his experience to ensure that readers could reconstruct in their minds what he had seen first-hand. This technique for making credible his testimony also relied on Daston and Galison’s notion of ‘virtue epistemics’ (Daston and Galison, 2007, pp 39–42). The ability to trust an observer’s testimony was shaped to a certain degree by their character. If an observer could be shown to be immoral or unethical in any capacity, it could be used to delegitimise them. Price had to carefully negotiate his persona in his account to position himself as a self-proclaimed objective seeker of the truth.

However, this posed a considerable challenge for Price because from the onset of his investigation he was deceitful toward Hope and his associates, concealing from them how he had marked the photographic plates he was using in the investigation to try and entrap the medium and expose any potential cheating. His trustworthiness was therefore suspect. When retracing the details of Price’s professed exposure of Hope from the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research it is essential to analyse the politics of the writing within it (Clifford, 2010, pp 1–26). If Price was so open about misleading and lying to spiritualists in order to prove that Hope was a fake, what is to say that Price was honest about his findings to members of the SPR and their journal’s readership? He could just as easily have manipulated his professed results to suit his own personal motives. There was primarily only his testimony to rely on.

The decision to investigate Hope was highly calculated. During the opening decades of the twentieth century, Hope’s ‘Crewe Circle’ – so named because it was based in Crewe, Cheshire – was one of the chief spiritualist groups in Britain to produce what was widely regarded by believers to be authentic examples of spirit photographs. Appetite for sittings with Hope was so insatiable that appointments were arranged weeks in advance. Hope’s many celebrity endorsements further contributed to his glowing reputation within the spiritualist community. Arthur Conan Doyle, the chemist William Crookes, and the suffragist and aid-worker Mabel St Clair Stobart were just some of the high-profile figures to support Hope’s legitimacy as a real psychic. These endorsements were all the more impressive given that Hope came from a disenfranchised, working-class background. He had to build his network of elite advocates from nothing. Price purposefully targeted Hope because of his important position within the spiritualist community. By the early 1920s there was no spirit photographer more renowned or respected in Britain. Exposing Hope as a fraud would strike a major blow to fake mediumship and cement Price’s status as a skilled psychical researcher (‘Investigator’, 1922, pp 484–486).

Price originally attempted to hold a sitting with Hope as early as 1915. He had written a letter to the medium, but received no reply. He tried again in March of 1921, but met with a similar result. Recognising that he was not going to receive any response from Hope without help from the spiritualist community, who acted as gatekeepers, Price set out to build a network of spiritualist associates in London. He eventually secured some contacts at the BCPS, which was one of the main spiritualist-run scientific institutes in Britain at the time. After a sequence of exchanges with the BCPS’s secretary Barbara McKenzie in November of 1921, an agreement was finally reached that the BCPS would host a sitting between Price and Hope (Price, 1922, p 272).

On 12 January 1922, Price received a letter from one of Hope’s representatives, notifying him that the medium would agree to a meeting so long as certain criteria were met. This kind of request was typical for most psychic investigations, and the aim was to control the conditions of the experiment. Giving too much power to either the medium or the investigator could undermine the integrity and results produced during an experiment. Thus, it was important to establish a set of balanced controls that benefitted both parties. More often than not, though, these controls merely created the illusion of parity.

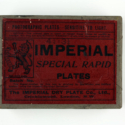

For this experiment, Hope requested that he be allowed to use his own camera, but to keep things balanced Price could examine the device before and after the photographs were taken. In turn, Price was allowed to bring a co-investigator with him to the experiment so long as the person was ‘sympathetic’ to spiritualism and not overly hostile. The letter explained that ‘If you decide to take this [offer], kindly confirm as soon as possible. The fee for non-members is £2 2s. 0d., to be paid on confirmation.’ Price agreed to these terms, and a date was eventually set for 24 February 1922. A set of further instructions asked Price to ‘provide a half dozen pack of ¼ plates for the experiment’, and Hope’s representative explained that ‘Imperial, or Wellington Wards’ were the preferred brands (Price, 1922, pp 272–273).

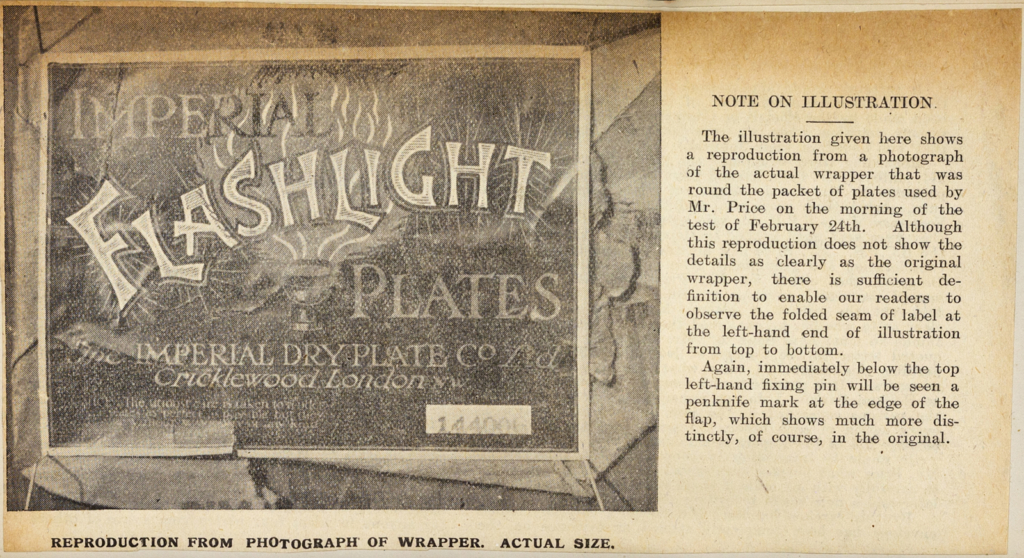

The type of approved photographic plate that Hope would allow in his sittings became the focal point of the case (see Figure 3). Given the difficulties Price experienced in arranging an appointment with Hope, he wanted to ensure that he maximised the possibility of catching any potential cheating during the planned session. It was likely going to be the only opportunity to do so. Thus, on 25 January 1922, Price visited the offices of the Imperial Dry Plate Company in Cricklewood, London to commission a special set of six ¼ photographic plates for his upcoming investigation (Price, 1922, p 273). Price explained his plan to the representatives at Imperial and they proposed to make a set of plates that were secretly marked with the firm’s logo, which was a lion (see Figure 4). These markings were applied to the plates using an X-ray apparatus, which was held by Imperial. More importantly, Hope and his associates would not be able to detect them with their naked eyes. When exposed to the chemical mixture during processing, however, the logo would appear and be transferred onto a print. If the lion logo did not appear on the photographic image, it could be assumed that Hope had likely swapped the supposedly blank plates Price had provided for ones with spirit extras already fixed on them. As Imperial explained to Price, ‘We have tested this method and find it quite infallible, and it is impossible for anyone to have adopted the same steps which we have with regard to these 6 plates’ (Price, 1922, p 273). The plates were also ‘Flashlight’ types that were highly sensitive and fast processing, which meant there was little time for any trickery to occur when preparing the results.

Three days after his visit, Price received a parcel from Imperial containing his specially commissioned photographic plates. To ensure that his investigation was perceived as open and transparent, he handed over the parcel in its original and sealed postal wrappings to his neighbour, H J Moger. The parcel was then sealed in a second layer of postal packaging before being sent to the SPR for safekeeping ahead of the meeting with Hope in a few weeks’ time (Price, 1922, p 274). This would become an important set of details later in the case when defenders of Hope questioned the reliability of the supposed precautions used by Price prior to the session. There were no impartial witnesses to verify that neither Price nor Moger tampered with the parcel prior to its shipment to the SPR. There was only Price’s word, which was not trusted because he actively sought to entrap Hope using invisibly marked plates (McKenzie, 1922, pp 740–741).

On the morning of the investigation on Friday 24 February 1922, Price met James Seymour at Holland Park Station in London. The two men had never met before but would travel together to the British College of Psychic Science where the meeting with Hope was to be hosted. Seymour was to be Price’s co-investigator, and was recommended to the role by the Society for Psychical Research, who viewed him as a reliable collaborator with sound knowledge of both professional conjuring and photography. These were two essential skillsets for an investigation of this kind. Seymour was also a member of the Magic Circle, a group of elite stage magicians in Britain who devoted much energy to exposing fake mediumship (Price, 1922, p 275).

The Society for Psychical Research also felt it necessary to have a corroborating testimony to confirm the details of Price’s account afterward. A key way of strengthening one’s report on a psychic investigation was by producing corroborating testimonies using other credible witnesses who had attended the same event. Seymour’s role, therefore, was essential for establishing the veracity of Price’s own testimony. If two respectable men with expertise in both stage magic and photography claimed to have witnessed the same thing during their sitting with Hope, their reports were most likely reliable. This approach to producing credible testimonies had a long tradition in the sciences, and it is a kind of ‘collective empiricism’ (Price, 1922, p 275).

Eric Dingwall, the Research Officer for the Society for Psychical Research, was also present at the station, and handed over the sealed parcel of plates to Price and Seymour. These were allegedly still wrapped in the double packaging prepared by Moger and Imperial respectively. To avoid suspicion, Moger’s postal wrappings were removed from the parcel at this stage so that only Imperial’s packaging remained. The three men went over the details of the plan one more time and agreed to meet back at the Society for Psychical Research later that day to record Price’s and Seymour’s testimonies while their impressions of the event were still fresh in their minds (Price, 1922, p 275).

Price and Seymour left Dingwall and headed over to the BCPS, where they were greeted by Barbara McKenzie. Price explained in his exposé how he and Seymour ‘were very cheerful and did all we could to impress her with the fact we had come to Mr Hope in a friendly manner’ (Price, 1922, p 275). In reality, Price had every intention to entrap Hope. Thus, he was open about his disingenuousness towards Hope and his associates in his exposé of the event. This undermined the integrity of his testimony because it demonstrated that Price was willing to mislead people in the pursuit of gaining his desired results. His ‘epistemic virtues’ were therefore compromised from the onset of the meeting (Daston and Galison, 2007, p 39–42).

Price and Seymour were then escorted to the top floor of the BCPS where they met Hope and his personal assistant Mrs Buxton. The four of them sat at a table together, and Price placed the sealed parcel with the photographic plates before Hope and his assistant to inspect. Hope asked Price to undo Imperial’s postal wrapping, which was carefully cut open using a knife. The unopened box of plates was placed back on the table for examination. Hope carefully scrutinised the box’s packaging to see if it had been tampered with, but nothing was detected. Buxton then remarked how it was a box of ‘Flashlight’ plates, which were not the ones typically used by Hope. Price quickly responded to this concern, stating how ‘I told the Imperial people that they were for a portraiture inside a London room, and they suggested flash light’ as the best option for maximising results (Price, 1922, p 276). There was some further scrutiny of the box’s packaging, and debate about the exposure speed of the plates, before everyone agreed that they were acceptable for use in the investigation.

Already we can see that the objects used during the Hope-Price affair were central to its re-telling. From the postal wrappings and packaging to the exposure speed of the plates, the full range of materials used for the investigation was carefully scrutinised by Hope and his associates and meticulously recorded in Price’s testimony. Those reading the narrative in the pages of the SPR’s journal could virtually follow along in the proceedings as they unfolded (Shaping and Schaffer, 1985, pp 55–65). Much care was also taken by Price to assure everyone that the materials provided were genuine and appropriate for an investigation of this kind. Here again, Price was purposefully withholding information on how the plates were secretly marked, assuring Hope and Buxton that everything was above board. This purposeful attempt to reassure them while concealing his plans to entrap Hope with secretly marked plates was, in itself, sufficient grounds for most critics to pronounce the investigation both biased and compromised from the onset.

Once the packet of plates was deemed suitable for the session, Hope collected the ‘dark-slide’ for his camera from his darkroom. When he returned, he explained to Price and Seymour how the slide was the component that held the plates in place for photographing and protected them from overexposure to light. He handed the dark-slide to Price and Seymour for examination and both stated that everything seemed satisfactory (Price, 1922, p 277). While examining the dark-slide, Price also secretly marked its frame with a small pricking device hidden on his thumb. This was done as an extra control to determine later whether Hope had swapped the dark-slide during the sitting. Price was then invited into the darkroom to inspect the space prior to the photoshoot. On entering the darkroom Hope instructed Buxton to ‘look after Mr. Seymour’, before closing the door. Thus, from this stage in the narrative, Price was separated from his corroborating witness and we only have his testimony to rely on (Price, 1922, p 278).

Inside the darkroom, Hope lowered the lights and handed the packet of plates to Price. He was instructed on how to load two plates onto the dark-slide. Next, Hope asked Price to repack the four unused plates, and it was at this moment, when Hope believed Price was distracted and hindered by poor visibility, that he allegedly gave a half turn ‘two or three paces from the light – put the dark-slide to his left breast pocket, and [took] it out again’ (Price, 1922, p 278). Price postulated that this was likely how the Imperial plates were swapped. An identical second dark-slide with plates already loaded on it was probably hidden on Hope’s person. It is significant as well that this important moment in the experiment occurred when Price was separated from Seymour, meaning there was no corroborating witness on hand to verify this key moment in the testimony; a detail that would later be leveraged against Price’s claims.

Before re-entering the studio for the photoshoot, Hope said to Price, ‘Would you like to mark the plates and write your initials on them?’ This, he explained, was a precaution that some sitters insisted on using as an extra control to inhibited any potential cheating. Price responded reassuringly that he did not believe it was necessary, feigning confidence to Hope that everything seemed above board (Price, 1922, p 278). Of course, there were hidden controls in place to check if the photographic materials were changed. However, Price’s desire to feign confidence in the proceedings was part of his ploy to self-fashion a persona as an amicable investigator, who was not there to try and expose fraud, but simply to witness some extraordinary phenomena. Hope then instructed Price to carry the dark-slide into the studio so that it could be loaded into the camera under his guidance.

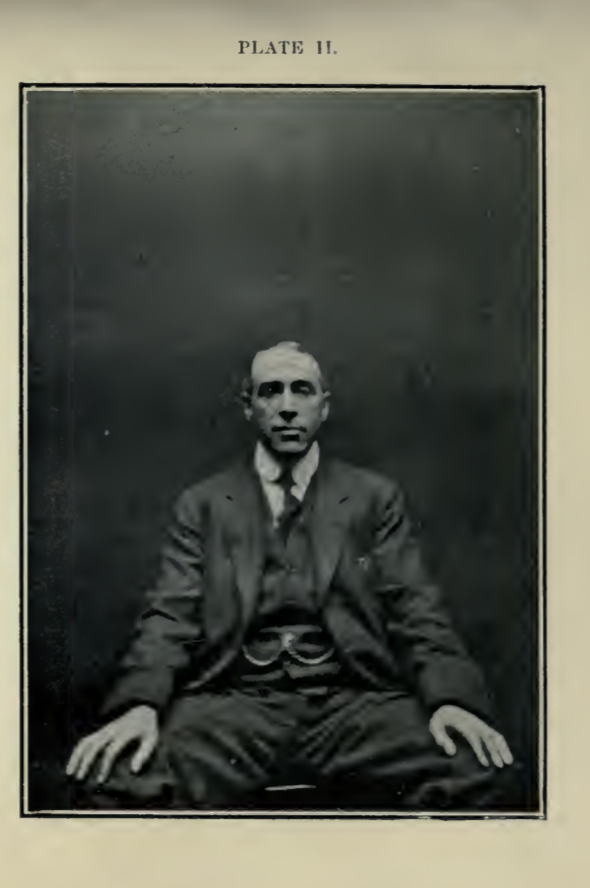

While walking across the studio toward the camera, Price quickly looked at the dark-slide one more time to check whether the prick marks were still on its frame, and he recorded in his testimony that ‘they were not’. This admission in his testimony was no off-hand remark, and Price wanted to confirm irrefutably that Hope had already swapped the dark-slide containing the X-ray marked plates. If any spirit were to appear on them now, they would almost certainly be fakes. Seymour and Buxton re-joined the investigation inside the studio and the dark-slide was loaded into Hope’s camera, which was described as an ‘old Lancaster model’ (see Figure 5). Price remarked that the camera ‘must be a curio’ because it was a fairly antiquated piece of technology by 1922. The camera was originally given as a present to Hope in the early 1900s by the Archdeacon of Stockton, Thomas Colley. It was likely manufactured in the late 1890s (Price, 1992, p 279; and Doyle, 1923, p 15). Unlike the more contemporary cameras of the 1920s, the Lancaster model was simpler to operate and easier to manipulate. It was exactly the sort of equipment other spirit photographers had been using throughout the second half of nineteenth century. More importantly, many of these photographers were debunked as frauds (Kaplan, 2008). This detail would have been known to other investigators of spirit photography, and was purposefully highlighted in Price’s testimony.

Hope then set about adjusting the camera lens so that the photographs could be taken, while Seymour observed him carefully. Price took a seat for his portraits and was given a final set of instructions on how to position himself. Hope drew back the shutter of the dark-slide to begin exposing the first of the two plates. As Price recalled, ‘during the exposure I counted in my mind, “1 and 2 and 3 and,” etc. and counted in that way up to nineteen…an abnormally long exposure’, especially given that they were using ‘Flashlight’ plates. Price believed this to be highly suspicious and it further reinforced his belief that Hope was using a different set of plates to the ones he had originally provided. Buxton than asked Price to change his pose for the second photograph, and while the image was being captured, there was again a long exposure time (Price, 1922, p 279).

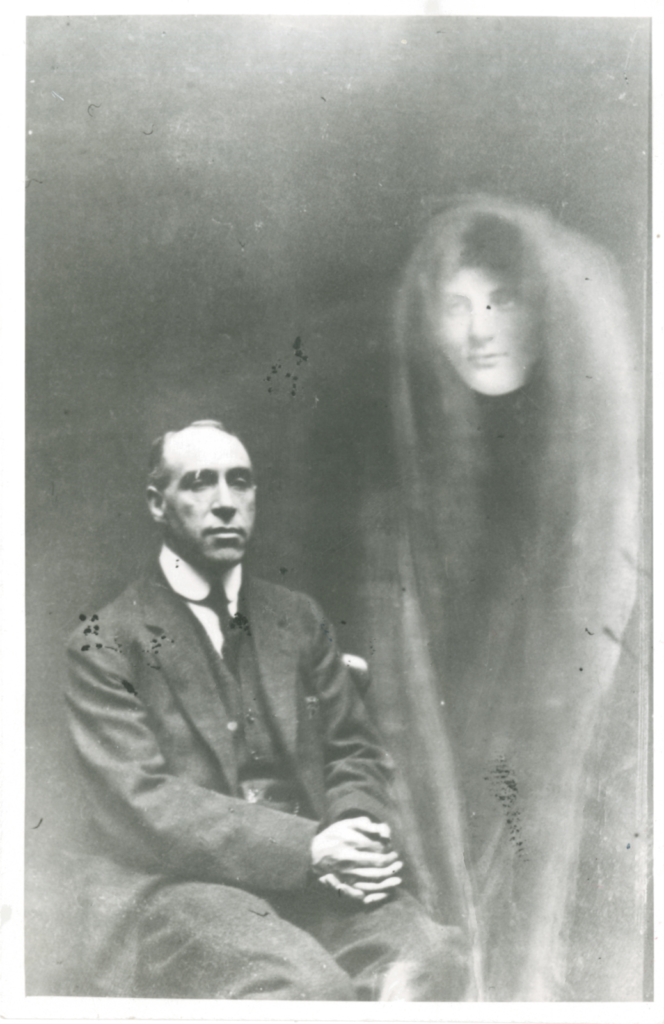

Seymour and Price were now both invited into the darkroom to oversee the plates’ processing. A standard mixture of chemicals was used for developing the images, but Price grew suspicious when to his surprise ‘instead of the plates flashing up black at once, as it seemed they ought to have done had they been those I brought with me, the plates developed slowly (as ordinary slow plates would do’ (Price, 1922, p 280). The inference was clear: Price was deducing that Hope had switched the plates. Finally, after a short period of waiting, a spirit extra appeared on the second of the two plates (see Figure 6). Price was allowed to inspect the spirit image under the red light of the darkroom and while doing so, he observed that ‘the trade mark of the Imperial Plate Co. was not coming up on the plates’. This was further confirmation that Hope likely cheated during the investigation (Price, 1922, p 280).

Typically, sitters were not allowed to keep the plates Hope used during their photographic sessions. Instead, Hope retained them and posted prints to his sitters a week or so later. While packing up, Price managed to convince Mrs Buxton to allow him to take the first photographic plate, without the spirit extra on it, home with him. She asked Price what he wanted to use it for and he explained that he ‘fancied it was a good portrait’ of himself. There were no objections and Buxton found a small box to transport the plate in so that it would not fog through overexposure to the light. This was a particularly important piece of evidence to collect because it provided Price with a plate he could fully inspect to see if the Imperial logo it should have contained would transfer to any print it produced (Price, 1922, p 280). It was therefore an important test tool for his research.

After the investigation, Price and Seymour immediately travelled to the SPR where they gave their testimonies to Dingwall and some of his associates. Price firmly believed that Hope was a fraud, which was corroborated by Seymour. Later, when Price produced some prints using the plate Buxton had given him after the photoshoot, the printed portraits contained no trace of the Imperial logo (see Figure 7), which was interpreted as further damning proof of forgery. Finally, when his other print arrived in the post from Hope, the spirit photograph did not include the logo either. This seemed to be conclusive evidence that the original specially commissioned plates were swapped for others. So far as Price and the SPR were concerned it was an open and shut case. Copies of these prints were included with Price’s published testimony in the SPR’s journal for readers to examine.

Could an objective reader accept any of Price’s account as truthful? As we will see in the next section with James Hewat McKenzie’s critical response to Price’s alleged findings, for these claims to hold any real weight there was still the issue of whether or not Price’s testimony could be accepted as credible. Much was made of whether the plates used at the onset of the sitting with Hope were even the same ones supplied by Imperial. The only person who could vouch for them being secure and uncompromised prior to the meeting was Price. It did not help his credibility that doubt surrounding the integrity of the packaging was already questioned in his own exposé published in the SPR’s journal. Price recounted how Buxton displayed some concern over the wrappings of the packet of plates at the start of the sitting, which she examined ‘very minutely’ and asked ‘whether the packet had been tampered with’. Price reassured her that the contents were completely intact (Price, 1922, p 276). However, these suspicions only grew as the affair wore on, and there continued to be suggestions by Hope’s supporters that Price possibly swapped the marked plates provided by Imperial before even meeting with Hope. If this allegation was true, the whole case was predetermined, because Price had already fixed the results.

2. James Hewat McKenzie’s defence of William Hope

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221707/004Too often the history of spiritualism is told solely through the perspectives of sceptics and disbelievers. When the viewpoints of believers are included, it is usually to highlight how spiritualists and telepathists were either superstitious, credulous, or suffering from some form of ill-health that clouded their judgement. Trevor Hall’s writings are emblematic of this kind of scholarship (Hall, 1962). More recently, there has been a surgency of secondary literature, where some scholars claim that the history of spiritualism is a topic that is typically pushed to the margins of science studies (Josephson-Storm, 2017; and Raia, 2019). These arguments are misleading, and there has been a strong body of work on the history of spiritualism’s relationship to the sciences since the seminal work of Janet Oppenheim in the mid-1980s (Oppenheim, 1985). Even so, within the vibrant research culture of science and spiritualism studies, the voices of believers remain subordinate to those of sceptics and disbelievers (e.g., Lamont, 2013). Fundamentally, these ‘rationalist narratives’ tend to skew a more complex historiographic discussion and, as Roger Luckhurst reminds us in The Invention of Telepathy, it is important to explore the topic of science and spiritualism without ‘prejudging’ the actors (Luckhurst, 2002, p 1).

It is for this reason that a re-telling of the Hope-Price affair should provide a more balanced narrative that seriously considers both sides of the case. Such an approach helps us to better understand on their terms why supporters of spiritualism held their beliefs. To a certain extent, studies of spiritualism should follow the lead of ethnohistory in pursuing a richer and more sensitive historical narrative. There are some important lessons to be learned from current ethno-historical discussions on ‘shared authority’ that would allow for a more respectful story about spiritualists’ beliefs and practices to be told (Frisch, 1990; Adair, Filene and Koloski, 2011; Lonetree, 2012; Tuck and Yang, 2012). The application of a ‘thick description’ is once again useful for recapturing these marginalised voices (Geertz, 1973, pp 25–26).

Much like Price’s testimony, where the objects used during the investigation took centre stage, the importance of material evidence was also core to the challenges forwarded by Hope’s defenders. If believers were to prove Hope’s innocence, their case rested with the surviving physical evidence. This further underscores the essential role of objects in the history of spiritualism’s relationship with the sciences. Price’s testimony may have been the primary piece of evidence used to defame Hope’s mediumship, but without further material proof it was a weak case and could be fairly easily delegitimised by spiritualists. Therefore, a full investigation of the physical evidence dominated the deliberations that ensued in the spiritualist press after the publication of Price’s exposé. Defenders of Hope demanded the facts, and with them, a meticulous interrogation of all the surviving objects used during Price and Hope’s meeting.

The most vocal early defender of Hope was the President of the BCPS, James Hewat McKenzie. Originally from Scotland, McKenzie made a name for himself within British spiritualists circles after carefully studying mediumship over many years. His main published work was Spirit Intercourse: Its Theory and Practice (1917), but he also published several smaller pamphlets on related topics during the 1910s. An unwavering believer in spiritualism, McKenzie famously suggested that the magician Houdini was secretly a medium, and that his extraordinary feats could only be explained as a product of psychic forces (McKenzie, 1917, pp 127, 132–134). He eventually founded the BCPS in 1920 with his wife Barbara, and their aim was to create an institutional hub for fostering critical research that would corroborate the existence of psychism as real. McKenzie had worked with several major psychic figures in pursuing this aim, including Gladys Osborne Leonard, Franek Kluski, Maria Silbert, and Eileen J Garrett. He was therefore seen, especially amongst believers, as a highly credible psychical researcher. He also held strong ties to some of the leading members of the SPR, regularly exchanging ideas with them (Buckland, 2005, pp 246–247).

McKenzie’s emergence in the Hope-Price case was no doubt linked to his wife’s role in arranging the meeting that led to the supposed exposure at the offices of the BCPS. The published article in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research was a major scandal for the BCPS, and it was important that they forwarded a robust challenge to Price’s professed findings. According to McKenzie, Price’s meeting with Hope was not a judicious investigation of the medium’s powers, but a slanderous accusation based on insufficient evidence. His most significant defence of Hope was published as a timeline of the events surrounding Price’s investigation, which appeared in the spiritualist periodical Light under the title of ‘The Total Collapse of the Price-Hope Case’ (McKenzie, 1922, pp 740–741).

The BCPS was initially slow to respond to the Hope scandal, and McKenzie argued that much of their delay was due to insufficient access to the physical evidence supporting Price’s claims. As it was reported in Light in November of 1922, ‘the S.P.R. have refused until the present month to lay the full facts before the College for examination’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 740) For defenders of Hope, the key pieces of evidence were not the plates themselves, although they were certainly important, but the postal wrappings and product packaging, which they argued required careful inspection to determine whether any tampering to them had occurred prior to the investigation on 24 February 1922. There was a tremendous amount of information to consider, and McKenzie believed that to help readers fully absorb the details of the case, it was essential to sketch a timeline of the events surrounding the investigation. By reconstructing the timeline in this manner, he believed it was easier to thresh out the subtleties of Price’s testimony and carefully unpack its significance. It also allowed readers to mentally recreate the storyline in their minds, which, in a sense, represents a form of ‘virtual witnessing’ (Shaping and Schaffer, 1985, pp 55–65).

As McKenzie explained in the beginning of his article, Price visited the BCPS on 24 February to investigate Hope’s mediumship. However, in the weeks that followed, further examination into the physical evidence of the case continued. On 4 March 1922, a parcel arrived at the SPR, which contained ‘four undeveloped photographic plates’, which McKenzie states were sent anonymously (McKenzie, 1922, p 740). From a close reading of the original exposé in the pages of the SPR, the parcel most likely came from one of the investigators. As recorded in the original narrative, it was when Hope instructed Price to pack away the remaining four unused photographic plates that the alleged swap of the dark-slides occurred (Price, 1922, p 278). It was an important set of details, and therefore, it stood to reason, that either Price or Seymour kept the additional plates for safekeeping after the investigation ended. McKenzie and his colleagues also rightly argued that it was suspicious that the identity of the sender was unknown. To Hope’s defenders, it suggested that the whole proceeding was suspect.

It was at the end of May when Price’s article was published in the SPR’s journal, and according to McKenzie this was a ‘complete surprise’ to the BCPS’s officials. Prior to its publication, none of the BCPS’s members knew that Price was corroborating with the SPR in the investigation of Hope (McKenzie, 1922, p 740). It was clear from McKenzie’s article that he and his associates were deeply unhappy that Price’s findings were not brought forward to the BCPS for consideration prior to their publication. This tactic, which was clearly employed to limit the opportunity for Hope’s supporters to stop the allegations from being released, was seen as quite undermining to the relationship between the two organisations. Up until this point, the BCPS and the SPR were quite amicable toward one another. The Hope-Price affair, however, drove a permanent wedge between the two groups, with long-term consequences and antagonisms resulting from it (Nelson, 2013, p 159).

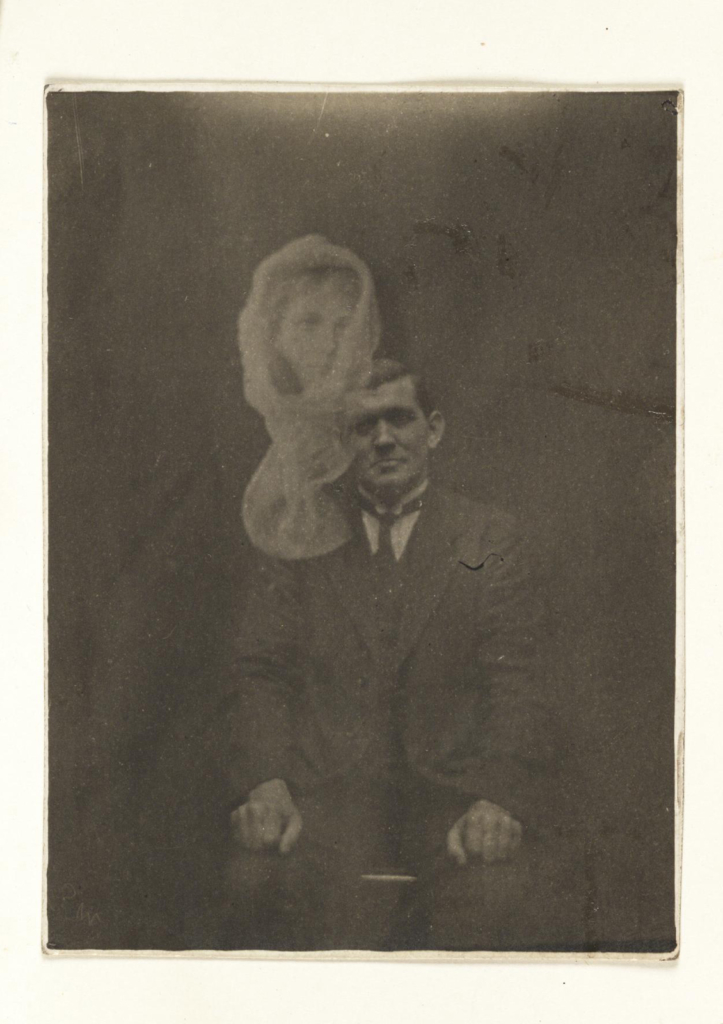

McKenzie contacted the SPR on 7 June 1922, along with The Society for the Study of Supernormal Pictures (SSSP) with the view of establishing a joint committee to fully investigate the charges against Hope. The SSSP was founded primarily by a group of spiritualists in 1918 with the expressed mandate to investigate all claims of supposedly genuine spirit photography. Its first president was the physician Abraham Wallace, and Arthur Conan Doyle served as one the society’s three vice presidents (Fischer, 2004, pp 77–79). It was McKenzie’s contention that such a collaboration between three different groups would provide a more impartial set of findings on the matter (McKenzie, 1922, pp 740). However, the SSSP was the leading spiritualist-run group to specialise in spirit photography in Britain, and it was no wonder McKenzie wanted them involved in a joint committee to investigate Price’s claims. They were overwhelmingly in support of Hope’s mediumship. Wallace, for instance, had previously participated in a sitting with Hope, and firmly believed that the results produced were examples of genuine spirit photographs (see Figure 8).

The SPR were alert to these biases, however, and two weeks later, on 23 June, McKenzie and his associates at the BCPS received a reply from the SPR who declined the request, citing ‘no good purpose could be served by such an inquiry’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 740). After receiving this rejection, McKenzie changed tactic, and proposed that if the SPR was unwilling to work together on a review of the case, would they at least share the full set of evidence with the BCPS for examination, especially ‘the X-ray marked plate belonging to Mr. Price’s experimental packet…[which] was one of the two plates said to have been abstracted by Mr. Hope at the experiment’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 740). The SPR continued to rebuff McKenzie’s requests, and frustrated by their unwillingness to cooperate, he threatened legal action if they did not share the evidence, arguing that Price’s accusations were inflicting a ‘grave injury…to Mr. Hope and Spiritualism generally’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 740).

Weeks passed and there were several more exchanges between McKenzie and the SPR. Finally on 31 October 1922, Eric Dingwall brought a box containing some of the physical evidence from Price’s investigation to the BCPS for examination. However, as McKenzie contended, key evidence was still withheld. For example, the postal wrappings from both the Imperial Dry Plate Company and Price’s neighbour Moger were missing. McKenzie explained to Dingwall that these objects were essential to the case because they were ‘important links in the chain of evidence’. Their sealed integrity prior to the meeting with Hope on 24 February had to be confirmed as best as possible. Dingwall promised to retrieve the wrappings for McKenzie and arrange another meeting so that the BCPS could inspect it first-hand (McKenzie, 1922, p 740–741).

Not until early November of 1922 did McKenzie finally view what he believed to be four key pieces of evidence in the Hope-Price case: (1) the original box for the ‘Flashlight’ photographic plates, which were sent to Price directly by Imperial; (2) the brown paper postal wrapping that Imperial used for sending the box of plates to Price; (3) the inner envelope that Price’s neighbour Moger used to seal the package sent by Imperial. This envelope had six wax seals on it to ensure that its content could not be compromised ahead of the investigation without detection; and (4) the outer postal wrapping that enclosed everything together and protected it in transit on route to the SPR for safekeeping prior to the meeting between Price and Hope. It is significant that McKenzie noted that the envelope that Moger prepared with six wax seals was ‘completely broken and seriously damaged’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 741). It was therefore impossible to determine if those seals had been broken prior to the sitting with Hope.

More importantly, however, was the original packaging for the box of ‘Flashlight’ photographic plates. In McKenzie’s opinion, ‘it was quite obvious that the Imperial Company’s Flashlight label had been disturbed’ (McKenzie, 1922, p 741). The packaging had apparently been manipulated in a subtle way so that it was possible to remove the plates whilst maintaining the structural integrity of the box. What this meant was that Price could have removed the specially commissioned marked plates for others that were blank. Any photograph produced with a spirit extra was guaranteed to not have the invisible Imperial logo on it. It seemed to be a carefully arranged trap to destroy Hope’s reputation and ensure a guilty verdict. McKenzie shared a copy of an image of the ‘Flashlight’ box for readers to scrutinise in the pages of Light (see Figure 9). This information was transformative for the case, and according to McKenzie, ‘It will be obvious that this vital and important discovery nullifies all the other evidence produced by Mr. Price against Mr. Hope, if it can be proved that the packet did not leave the hands of the Imperial Plate Company in this condition’; that is, with the small fold allowing the plates to be removed without detection (McKenzie, 1922, p 741).

To further support his theory, McKenzie met with Imperial to give them the packaging for the Flashlight box so that they could inspect it and determine whether it had been tampered with. A few days later he received a formal written response from the firm, stating the following:

After careful examination of the label attached to the wrapper in question, we are of opinion that one end of the label has been unstuck from the wrapper and folded back so as to leave the ‘ear’ of the brown paper wrapping uncovered. This ‘ear’ also appears to show signs of having been unstuck and refolded (McKenzie, 1922, p 742).

This was an incriminating testimony against Price’s claims and suggested a strong possibility that someone had perhaps manipulated the contents of the box with a view to not being caught. For McKenzie it was confirmation that Price, potentially with the help of his neighbour Moger, rigged the investigation so that they could frame Hope as a fraud. The obvious benefit being that Price would then establish a name for himself as a key figure among British psychical researchers. For supporters of Hope, Price’s whole case stood or fell with this key piece of evidence. If it could be shown that it was Price or one of his associates who swapped the plates for blanks ones, Hope would be fully exonerated. Given that there were no other corroborating witnesses to confirm Price’s claims about the events that transpired in the darkroom that led to the dark-slide supposedly being exchanged for a different one, the physical evidence that McKenzie put forward was somewhat more compelling from an empirical standpoint.

In addition to the physical evidence suggesting the possibility that someone, such as Price or Moger, could have tampered with the box of Flashlight plates prior to the investigation with Hope occurring, there is further corroborating evidence to consider. In Price’s testimony, there is a section in the narrative where Buxton is described as being suspicious of whether the package’s seal had already been broken (Price, 1922, p 276). This was important corroborating evidence. Taken together it validated the view that the Flashlight plates were probably compromised, and therefore unreliable objects to rest a case about fraud on. Nevertheless, much time had passed between February and November of 1922, and in that period the surviving physical evidence could have easily been damaged. The alleged manipulation of the box’s packaging could have also happened after the investigation. For instance, because there is no documented record of the box by either Price or the SPR, McKenzie and his associates at the BCPS could just as easily have damaged the packaging on purpose to discredit Price and vindicate Hope. Without an impartial agent to oversee both sides of the deliberations, much rested with the veracity of both claimants. It was therefore an extremely muddy conclusion regardless of which narrative one examined.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/221707/005Traditionally the history of spiritualism’s engagement with science has been framed as a product of the so-called ‘crisis of faith’ that emerged during the nineteenth century (Oppenheim, 1985, pp 1–3). As scientific explanations of the natural world began to displace older religious ones, there was a rise in secular thinking (Larsen, 2006; Lane, 2011; and Franklin, 2018). It was within this cultural landscape that spiritualism’s appeal grew, as many nineteenth-century figures appropriated it as a way of reconciling their fears about the afterlife and the loss of traditional religious faith. However, as a careful retracing of the Hope-Price affair shows, these conflicts may have started out as debates over belief, but inevitably they became critical discussions about evidence, or lack of it. Thus, when exploring the history of spiritualism’s relationship to the sciences, we should not think about it as a core example of a ‘crisis of faith’, but instead as what the historian Peter Lamont has termed a ‘crisis of evidence’ (Lamont, 2004, pp 897–920). The foundation of both Price’s exposure and McKenzie’s defence rested with the objects and testimonies used to support the allegations. Belief as to whether spirits and psychic forces were real was of secondary importance to the case.

To explore these complicated issues, I retraced the details of Price’s investigation of Hope’s spirit photography. By providing a more balanced story that compared the sceptic’s account with that of a spiritualist believer, a richer narrative emerged. This was not the great unmasking of a charlatan by the hands of a principled sceptic as it is usually remembered, but a muddier story where a group of derided spiritualists forwarded a robust, evidenced-based defence in support of a medium (Polidoro, 2011, pp 20–22). Hope was the victim, in this alternative account, and the clever trickster was the investigator trying to expose him through mischievous means. The standard rationalist narrative of the relationship between spiritualism and science is therefore flipped on its head. It was almost certainly the case that Hope fabricated fake spirit photographs, but the evidence used by Price to try and delegitimise him was hardly watertight.

The legacy of Price’s investigation of Hope is clouded by the unreliable evidence surrounding the case. Because both sides of the debate had a vested interest in the investigation’s results, the ability to trust either side’s testimony is difficult. The Hope-Price affair, therefore, is a useful case for exploring the importance of virtue epistemics in scientific investigations, allowing us to understand how historical actors can work with the same set of evidence and still interpret it in remarkably different ways to serve specific interests. Science, even in its alternative form, is never neutral. The history of spiritualism’s relationship with sciences continues to be hotly contested to this day. It provides an important lesson about the limits of any kind of evidence when dealing with extraordinary phenomena. The Hope-Price affair should not be commemorated as a key moment in scientific rationalism’s attempt to disenchant the modern world, but as a useful example for understanding the boundaries and limits of science.

Remembering the Hope-Price case is also a helpful exercise for expanding the remit of the history of science and spiritualism. Objects were fundamental to this investigation and its aftermath, and by closely following in the details of the story through a careful reading of two surviving testimonies, we can see how fundamental material culture was for psychical research in this period. Even so, the unstable nature of the testimonies, which drew on these physical pieces of evidence, complicates the way we make sense of their significance, and underscores why more material studies of science and spiritualism are needed. Far too often, the history of spiritualism’s relationship with science is told through the narrow perspective of sceptics’ and disbelievers’ accounts. What this study demonstrates, however, is that the story of spiritualism, like any form of interaction between belief and science, is extremely complicated. To arrive at a more wholistic understanding, we need to broaden our focus and bring in more perspectives, kinds of data, and voices. The story of the Hope and Price may have begun with a collection of photographs, but through them, a more nuanced narrative about the making of the modern science unfolds.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to the AHRC for their support in funding this research as part of The Media of Mediumship project (AH/V001140/1). I am also deeply indebted to Emma Merkling for her tireless efforts in collating the archives of the Hope-Price case for my research. Without her support, this paper would never have been possible. Equally, Christine Ferguson has been an amazing friend and collaborator, and her always brilliant and sound advice was invaluable to the intellectual development of this work. The staff at the Senate House Library and the National Science and Media Museum were extremely accommodating during my research, and I appreciate the support and access they both provided to their collections. Finally, I want to thank Nanna Kaalund for quietly ignoring me while I muttered about this paper under my breath when writing it.