Communities & Crowds: a toolkit for hybrid volunteering with cultural heritage collections

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242209

Abstract

This toolkit outlines the steps taken by the Communities & Crowds project to give ownership to local volunteers to identify photographs that reflect their interests; to digitise them to museum standards; and to share these collections with a global audience via an online crowdsourcing project. Communities & Crowds is an AHRC-funded collaboration between the NSMM (Bradford, UK), the Adler Planetarium (Chicago, IL), National Museums Scotland (NMS) (Edinburgh, UK), and Oxford University (Oxford, UK). It re-examines the role of the museum volunteer by combining participatory research methods and online crowdsourcing techniques to explore how local communities can collaborate with digital volunteers around the world to increase discoverability of, and access to, the collections that matter to them. The toolkit and accompanying downloadable templates are intended to be useable and reusable for any heritage organisation that wants to work with volunteers to find stories in photographic collections that matter to those audiences.

Keywords

audience engagement, crowdsourcing, digitisation, Museum, museum audience, toolkits, volunteering

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Photographic collections can hold collective heritage and cultural memory; they can also speak to individuals and different community groups in specific ways. As cultural heritage staff, how do you support volunteers as they engage with these collections? How can you work with communities to use photographic collections to tell the stories that matter to them?

This toolkit outlines the steps taken by the Communities & Crowds project at the National Science and Media Museum (NSMM) to give ownership to local volunteers to identify photographs that reflect their interests; to digitise them to museum standards; and to share these collections with a global audience via an online crowdsourcing project.

The paper is broken down into seven different steps which are co-written by the Communities & Crowds project team and the staff at the Science Museum Group (SMG) who developed the tools and processes. They are intended as a starting point for any other institution interested in replicating this process. Here you will find detailed case studies written by the project collaborators and volunteers outlining what you need to know for each step along the way, from recruiting volunteers, setting up workflows and managing data, to developing crowdsourcing tasks and preparing for public engagement. You will also find downloadable templates which you can use to help set up your own version of this project.

Communities & Crowds is an AHRC-funded collaboration between the NSMM (Bradford, UK), the Adler Planetarium (Chicago, IL), National Museums Scotland (NMS) (Edinburgh, UK), and Oxford University (Oxford, UK).[1] It re-examines the role of the museum volunteer by combining participatory research methods and online crowdsourcing techniques to explore how local communities can collaborate with digital volunteers around the world to increase discoverability of, and access to, the collections that matter to them. A major aim of Communities & Crowds was to provide a ‘roadmap’ for other institutions to recreate and iterate this process of volunteer engagement with their own collections and communities.

The project was established in early 2021, amidst the Covid-19 public health crisis and resulting restrictions and closures, as well as a global social justice movement sparked in part by the murder of George Floyd in May of 2020. While this project is not explicitly aimed at museum decolonisation and anti-racism, it is rooted in a desire for institutions to better serve the needs and interests of our local communities. When we first established a call for project volunteer researchers, we opened up the opportunity to any local group who were interested in finding stories in museum collections that mattered to them. Out of this open call emerged the work that would become How Did We Get Here?, co-created with individuals from Bradford’s African-Caribbean community. This work centred on photographs from the mid-twentieth century which depict acts of racism and colonisation by individuals and institutions. As a project team, we adapted our methods and processes to ensure that project volunteer researchers and museum staff felt supported and that they had a safe space to engage with this difficult work.

Communities & Crowds started with a central concern: cultural heritage institutions have a long history of delivering in-person volunteering opportunities for individuals to learn skills and work with collections. Equally, there are many successful examples of using crowdsourcing for meaningful, collections-oriented engagement with volunteers online (Ridge et al, 2021). However, there are no examples or case studies which allow for a holistic volunteering opportunity throughout the entire process of selecting and digitising materials, creating a crowdsourcing project, and managing the online community and data in a space like Zooniverse (https://www.zooniverse.org), the world-leading platform for online crowdsourced research. To underpin our new process, we looked to co-creative models within the museum sector focused on participatory decision making (Benoit III and Everleigh, 2019; Simon, 2010). Through a co-creative model, the volunteers and project staff worked in dialogue to make decisions, overcome obstacles and develop the project outputs.

Throughout this process, we were aware that there remain considerable barriers in place for local communities to engage effectively with museum collections and archives (Lynch, 2019, 115–126). To address this, we applied a participatory action research (PAR) approach to co-create spaces where local and international volunteer researchers could connect with each other (Tzibazi, 2013). PAR centres the value of experiential knowledge to understanding an issue or problem, bringing together participant-researchers and practitioner-researchers to form a ‘community of researchers’ (Cahill, 2007, p 299) who explore the issue through making something together. Within heritage institutions, tensions often arise when working with collaborative or co-creative processes with local communities. These tensions tend to manifest from a conflict between the need of an institution to retain control over the outputs from a collaboration and the desire from the communities to have greater influence around how their interests are prioritised within museum work. A PAR-based approach without consideration of how to centre the interests and agency of the volunteers within an institutional framework can lead to frustration for both project staff and community participants. To address this, the Communities & Crowds process prioritises the volunteer researchers as the decision makers at each step of the project and recognises the need for museum staff to provide support, including labour, to realise their goals.

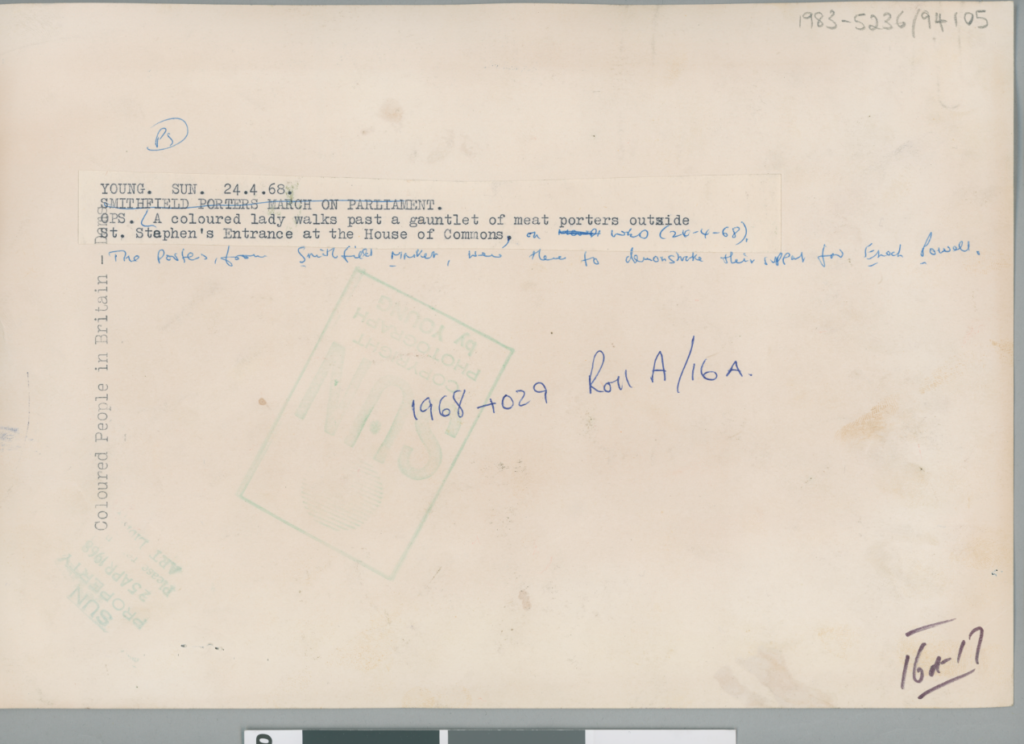

The set of case studies that follow in this toolkit are rooted in this PAR-based approach and based on the work of four volunteer researchers – Sandra Rowe, Maureen Rowe, Lincoln Anderson and Rebecca Smith – at NSMM between 2021 and 2023. Their efforts included documenting and digitising sections of the Daily Herald archive (DHA), as well as creating the crowdsourcing project How Did We Get Here? (Belknap et al, 2024). The DHA consists of ~3.5 million photographs from the Daily Herald, a mid-twentieth century national newspaper in the United Kingdom. The archive includes photographic positives taken between 1912 and 1964 with editorial markup on the front of the images, and rich metadata on the back. The archive is organised into biographical, thematic or geographic sections, with subdivisions for each section to allow for quick and easy access for the Daily Herald editors who needed an image for a new story. Because of this breadth of subject matter and the ease of the organisation structure, it provided an ideal photographic archive in which volunteers could find images that they found interesting and relevant.

As an example, one of the images digitised by the volunteer researchers shows a black woman walking in front of a group of white male demonstrators in support of the racist and fascist MP, Enoch Powell.

Reflecting on this image, volunteer researcher Maureen Rowe said:

…for me [this photograph] just says everything about standing up for who you are, speaking out. And when I look at [it] I think, yes, how things have changed. I think some things have changed, but we are still demonstrating. We are still fighting to be heard, to be seen. And so for me, yeah, that’s it. Every time I look at this picture, every time I see it, I just see this one strong black woman standing up for the community.[2]

We chose to work with photographic collections for both practical and ideological reasons. As objects, photographs can be scanned on a flatbed scanner rather than requiring a medium-format camera set up. As we had no expectation or demand for digitisation skills from our volunteer researchers, it was essential that the process for digitisation was easy to learn and didn’t require specific photographic or digital skills. We also choose photographs because they represent a broad and diverse subject area and have the potential to connect to a range of interests and identities. Photographs have a unique power to connect individuals and communities to their past, as an image is always a dialogue between the photographer, subject and the viewer of the image (Azoulay et al, 2023). Photographs that are held in museum collections represent the commemoration and preservation of a shared visual past, which offer modern audiences a way to engage with and reconfigure visual narratives that matter to them (Edwards, 2001; Edwards and Morton, 2015).

Working on the Daily Herald archive, the four volunteer researchers oversaw all decisions around what images to include in the project, what metadata they added to the objects, and the research questions and crowdsourcing tasks that were developed for How Did We Get Here?. A second project was conducted using these same processes at NMS using stereo photograph collections and developed by four Edinburgh-based volunteer researchers – Anna Votsi, Dennise Burns Zaragoza, Josh Murfitt and Annita Nitsaidou – which resulted in the crowdsourcing project Stereovision.

We argue here that through a PAR-based process of co-creation, which includes a volunteer-led experience throughout the entire project lifecycle, we have been able to centre the decision-making agency of volunteers and create a more impactful and meaningful volunteering experience. By following this process, cultural heritage institutions can create opportunities for local communities to decide what stories get told in museum collections and what gets made public through the creation of new digital resources. By incorporating crowdsourcing into the process, the volunteer project leads are able to introduce an international audience to the archival materials chosen for a given project, and to connect with new global communities around those materials, not only collaborating to increase access to materials but also creating space for discussion and sharing of their own expertise. Ultimately, this is a process to help break down barriers to the archive and diversify the voices that get to tell the stories of the collections, both in the physical institution and digital museum space.

This is not a toolkit to scale photographic digitisation in a heritage institution, but rather a method for deepening engagement with collections within local communities and empowering volunteers to become decision makers rather than participants in an institution-driven effort. For that reason, this toolkit is co-produced by the constellation of actors who have contributed to the project. As a collaborative, co-creative culture was core to the goals of this project we will briefly outline the roles that each author played in this project. Geoffrey Belknap and Samatha Blickhan were the co-Principal Investigators on this project. While Belknap led the museum-based work and Blickhan led the digital effort, they both had collaborative input and leadership in all areas of the project. Lynn Wray and Alex Fitzpatrick were post-doctoral researchers on the project and supervised the weekly volunteer sessions, the research framework and outputs for the project. Sandra Rowe, Maureen Rowe, Lincoln Anderson and Rebecca Smith were the volunteer researchers who selected NSMM items for digitisation and led the documentation and imaging process, as well as designing the How Did We Get Here? crowdsourcing project. Lawrence Brooks developed the documentation tool for the volunteer-led digitisation process; Adrian Hine supervised the development of the volunteer-digitisation process; and Matthew Hicks supported the volunteer recruitment process. Jacob Fox was a project intern, as part of an MA project at De Montfort University and worked with the volunteer researchers to create Zooniverse project content and assist with data pre-processing. Ruth Quinn was an internal staff advocate for the continued use of the volunteer outputs as part of a permanent gallery project at NSMM. Finally, Paulien ten Hagen was an MA student at Delft University of Technology who worked with the Communities & Crowds project as part of her dissertation.

This following seven steps are co-written by the Communities & Crowds project team and the staff at the Science Museum Group (SMG). They are intended as a starting point for other organisations and staff who are interested in replicating this process.

The following practice-driven sections are divided into two parts. The first focuses on in-person digitisation and documentation processes and workflows, and the second on creating a volunteer-led crowdsourcing project. The first section includes four steps: recruiting and working with volunteers; designing collaborative volunteer sessions; creating documentation workflows; and implementing digitisation workflows. The second section includes: creating community driven crowdsourcing workflows; using the new digital tools we developed for Communities & Crowds; and building a community-led Zooniverse project.

We end with two reflections on the practical implications of undertaking this work and the potential impact that it can have for your audiences. This process is not cost neutral, either in staff time or in technological requirements. We have endeavoured to keep the costs low whenever possible, but no successful community-led project can cost nothing. Institutions must invest resources in these collaborations, both financially or through staff support. In the final sections we outline the potential that this process has demonstrated for creating space for local communities to feel empowered to tell their own stories through gallery, library, archive and museum (GLAM) photographic archives. We also outline how this process can be adapted and augmented to different institutional settings and needs.

To replicate these processes, we have included downloadable templates which can be used and adapted for setting up a similar process with new communities in different institutional contexts. These templates are intended to be adaptable and reformattable and are a starting point for iterating this process with other photographic collections.

Recruiting and working with volunteers

Virtual volunteering offers organisations a powerful tool for deepening impact through volunteer engagement. Digital access certainly has its limits, particularly considering equity of access to reliable, at-home internet connection, but removing the need to travel can increase access to volunteer programmes and allow a more diverse range of people to volunteer (BrodeFrank et al, 2021). Just like traditional forms of on-site volunteering, successful virtual volunteering projects require careful planning and implementation to be a success. Here we will explore how organisations can create successful virtual volunteering opportunities through thoughtful planning, recruitment and management, beginning with the need to be clear about why your organisation involves volunteers.

For any form of volunteering to be successful, the host organisation must be clear about why it involves volunteers. This clarity helps shape the approach taken to developing volunteering opportunities and supports the creation of a culture of volunteering. If you don’t already have one, establishing an institutional framework describing the purpose of volunteering to your organisation is an important first step.

At SMG the purpose of volunteering is set out in their organisational policy and framework. This states the main aim of volunteering is:

…to achieve our operational, strategic and social ambitions more effectively.

This approach is reflected in projects like Communities & Crowds, which was designed to engage local audiences in helping to enhance our understanding of the images in photographic archives. As well as providing operational benefits, this project played an important role in delivering key strategic goals relating to SMG’s placemaking ambitions, enhancing collection and helping the organisation build deeper connections with its audiences.

To create effective and impactful in-person and virtual volunteering projects, roles need to be well-planned. This means ensuring they are designed and recruited to deliver operational, strategic and social impact. There are five steps that can be taken to achieve this:

- Give your planning a strategic focus: Take time to understand your organisation’s strategic ambitions and how volunteering can deliver them.

- Identify where virtual support is required: Work with colleagues to identify where volunteering can provide the greatest benefits.

- Plan the activity: Detail what the role will do, who will supervise it, identify training and resource requirements and set aside a budget.

- Identify target audience(s): By matching roles to specific audiences we can deliver strategic and social outcomes. For example, Communities & Crowds was targeted at people from Bradford who wanted to preserve, document or share their own cultural history through photographic archives.

- Work with community partners: Identify and work with community partners who can help recruit your target audience and provide training and support for you and your organisation.

At SMG, an Activity Outline is used to capture this information and ensure all aspects of the project have been considered before recruitment begins.

Once a role is planned, the next stage is recruitment. For projects like Communities & Crowds, where you are recruiting and working closely with a small cohort of volunteers, this can be split into three distinct stages:

- Advertising: Promote the role to the target audience(s) and community partners identified during planning.

- Meet potential recruits: Give potential volunteers the chance to learn about the role and your organisation before starting.

- Induction: Provide an informative and engaging onboarding process to the project and your organisation.

The approach taken here will not only dictate who and how many people you recruit but will set the tone for their overall experience participating. It is worth noting that larger online crowdsourcing projects will require a different, more informal approach for volunteer recruitment.

The first stage is to advertise your role. Traditionally, this is done via organisational websites and places like volunteer centres, universities and libraries. This approach is likely to attract a traditional volunteer but not necessarily the target audience identified during planning. To do this, you will need to work with the community partners identified at the planning stage. As well as being able to advertise the role directly to your target audience, they can help shape the role to make it more attractive and provide training for working with a new audience. For virtual projects you can work with national and international partners. Platforms like Points of Light and Volunteer Match allow you to advertise virtual opportunities to a global audience. Content-specific listservs and social media hashtags can be useful in this process, too.

Meeting volunteers before they start is important, as it allows both the institutional team and the volunteers to see if the role is a right fit. Traditional interviews can be too formal so alternative options like taster days or drop-in sessions can be more appropriate and help attract a more diverse audience. Whether hosted in person or online, these approaches should provide an opportunity for candidates to learn about the organisation and the role and, if possible, try it out.

Once recruited it is crucial to provide a good induction. This should provide volunteers with a welcoming and informative onboarding to the organisation and the role. Key things to consider include:

- Create connections: Use the induction as a team building exercise. Creating strong connections between members of the project is only going to be of benefit.

- Volunteering overview: Provide an overview of volunteering at your organisation, covering everything from knowing who to contact, to what to do if there is a problem.

- Role overview: Give volunteers all the information they need about the role and explain why it matters, how it contributes to the organisation’s ambitions and the impact they will make.

- Training: Provide volunteers with the training they’ll need to deliver the role effectively and safely.

- Make it fun: No one wants to attend a dull, lengthy training session so make it as engaging as possible. For virtual roles, consider how online tools can help.

Volunteers, like employees, require support and effective management. As well as ensuring you set time and resources aside to do this, you should:

- Form relationships with your volunteers: Get to know your volunteers and create personal connections with them. This will benefit you, the volunteer and the project.

- Be flexible: Don’t place a burden of expectation on your volunteers and be flexible if they need time out.

- Communicate effectively: Volunteers deserve to be kept informed about what is happening on the project and at your organisation, so communicate clearly, regularly and in various ways.

- Arrange team meetings: Make sure volunteers remain engaged by organising meetings (virtual or in person) where they can share what they’ve achieved, you can provide updates, and you can connect as a team.

- Provide enrichment activities: Arrange enjoyable activities that volunteers can participate in outside the role, e.g. curatorial talks or skills training (for greater impact, you can develop these in consultation with your partners and volunteers).

- Demonstrate impact: Volunteers like to know they make a difference, so take the time to demonstrate the impact they have made and showcase their achievements to external audiences.

Be aware that, unlike employees, if volunteers create original content when volunteering they own the copyright to the material they have created. If it is necessary to negate this, a copyright agreement should be put in place.[3]

Like in-person roles, virtual volunteering requires careful planning and implementation to be successful. While crowdsourcing projects may require a slightly different approach, in most cases the same essential method can be taken for online and offline opportunities: organisations must be clear about why they involve volunteers; roles must be carefully planned to maximise impact; and recruitment and induction must support wider ambitions and set the tone for a quality volunteering experience. When coupled with effective support and management, virtual volunteering can be a powerful tool for deepening impact and broadening access to your volunteering programme. If this approach is taken, as we have seen with Communities & Crowds, virtual volunteering can help deliver operational, strategic and social benefits for your organisation and the communities it serves.

Volunteer preparation and designing work sessions

When running any volunteer project, you will undoubtedly be working with a variety of people, each with different backgrounds and expertise that they will be bringing to the table. While that diversity of knowledge and understanding is vital to rich collaborative work, it is still important to ensure that your volunteers are equally prepared for whatever form of work awaits them.

In the case of Communities & Crowds, we divided the effort into two distinct phases: the digitisation phase and the Zooniverse crowdsourcing phase. Although together they comprise the whole of the project, each phase required bespoke planning to ensure that the volunteers felt comfortable and emboldened to contribute with confidence, regardless of their experience or expertise.

Structures for the volunteer sessions for Communities & Crowds drew from the learnings of the Bradford’s National Museum project[4] (2017–2020), which highlighted the need for better developed approaches to co-creation and collaborative research projects with local communities. As such, we designed the workflows for the project to be emergent and flexible, embedding spaces for conversation that enabled us to ensure that the interests of the volunteers were always centred and could allow us to shift and better reflect any desired changes over time.

Phase one: for a digitisation project

The digitisation effort was part of the first phase of the project work, and therefore needed to be carefully designed not only to introduce the volunteer researchers to the process of digitising archival materials, but also to get them comfortable with the archive itself. Early on, the volunteer researchers identified that they were most interested in exploring photographs and documents related to African-Caribbean stories from the Daily Herald archive; while this represented a vast source of fascinating stories related to immigration and cultural heritage, we knew that it would also include stories relating to colonialism and racism as well.

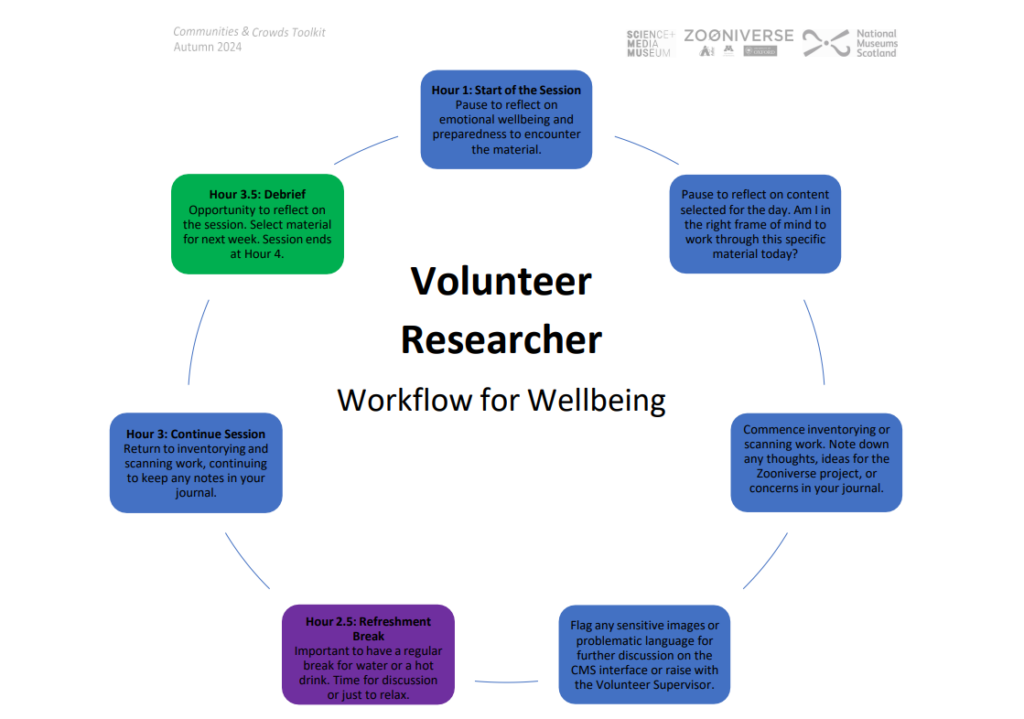

Understanding that this could be potentially upsetting or traumatising material to encounter, we decided to proactively address this from the start. We organised a session in collaboration with the Black, African and Asian Therapy Network (BAATN), where we discussed how best to support the mental health and wellbeing of the volunteers and staff working on this project, and how to maintain a safe environment throughout. Resources and contact information for further support were made available to volunteers, and appropriate resources were also carried over and made available to online volunteers on the Zooniverse project as well.

Based on recommendations made by BAATN, in-person volunteering sessions were structured around a wellbeing-centred workflow to ensure that there was always time and space for discussion, reflection and processing each week.

Each session would begin with self-reflection and checking in to ensure that volunteers were prepared to work on the materials they had previously selected for digitisation. Any problematic language or sensitive images encountered during digitisation were flagged at the volunteer researchers’ discretion and could be discussed further with a member of staff if necessary. Halfway through the session, the volunteers would take a break outside of the archives to enjoy refreshments from the Museum café, chat, relax and decompress. The volunteer researchers would then finish off the rest of the session, pausing at the end to debrief and prepare for the next week’s digitisation work.

The actual digitisation process was developed to require little specialist training beyond a few days of orientation by staff members. Volunteer researchers were taught how to inventory selected photographs using an application created specifically for this project (see the next section for further discussion), and then digitise the photographs using a flatbed scanner. A step-by-step guide with photographs was also created and kept on hand for reference during sessions.

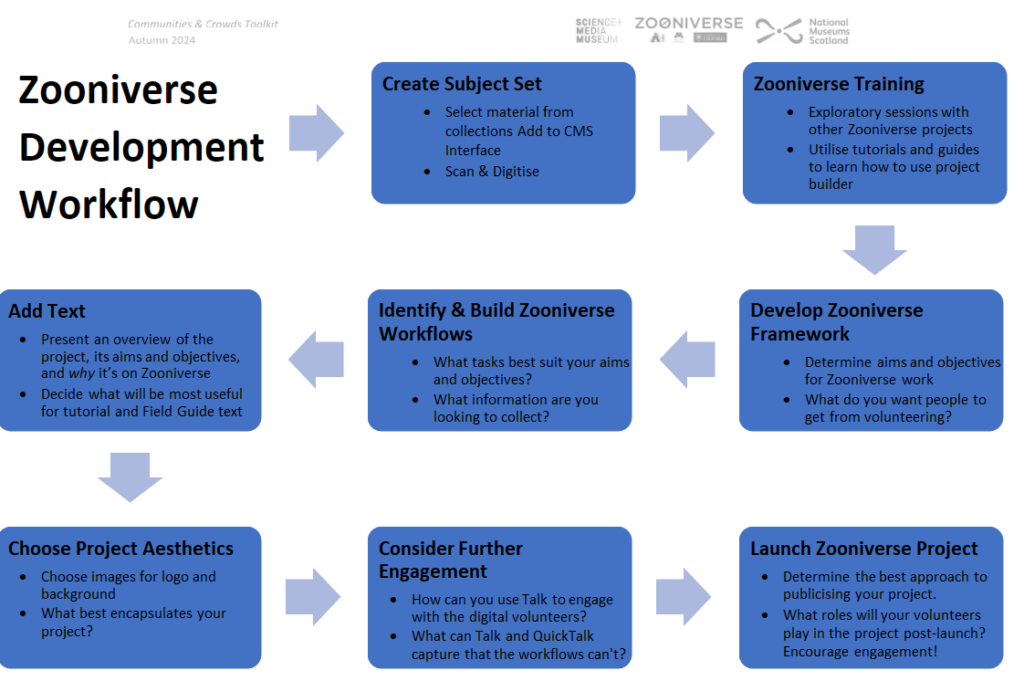

Phase one: for a crowdsourcing project (Zooniverse)

By the time we were ready to transition to the next phase of the project, the volunteer researchers had become comfortable working with one another and were intimately familiar with the archival materials as well. This was crucial as a foundation, as this next phase would involve moving into the less familiar world of online crowdsourcing. None of the volunteer researchers had any experience with online crowdsourcing or with the Zooniverse platform beforehand, and findings from our stage-one volunteer researcher interviews (conducted prior to the start of this phase) suggested that this unfamiliarity caused some volunteer researchers to feel nervous or uncertain at this part of the project. Using what we learned from developing the first phase of volunteering, we developed a structured approach to designing the Zooniverse project that embedded time for conversation and reflection alongside more experimental and exploratory sessions.

To get the volunteer researchers more comfortable with online crowdsourcing, we held hands-on workshop sessions in which they were invited to explore other projects hosted on the Zooniverse platform and get a sense of what was possible using these tools, as well as develop their own preferences around what kinds of tasks they enjoyed doing, and which they found confusing or wanted to avoid. This was complemented by discussion sessions, which provided the volunteer researchers with an opportunity to think aloud about what their personal goals were for their crowdsourcing project, how the available Zooniverse tools could facilitate those goals, and how they might enact those goals in a way that would be enjoyable for the online project participants.

We followed up this brainstorming session with a paper prototyping workshop in which the volunteer researchers were presented with some of the photographs selected for digitisation and asked to approach them as though they had never seen them before, simulating the experience of new volunteers on Zooniverse. They acted out some of the proposed workflows for the project and then reported back on their experience during a follow-up discussion session.

All of these exploratory and hands-on sessions ultimately gave the volunteer researchers a space to experiment with new ideas and techniques, with discussion sessions to further talk through their motivations and how they could be reflected in the resulting Zooniverse project. When it came to actually building the project using the Zooniverse Project Builder tool (https://www.zooniverse.org/lab), the volunteer researchers worked together to collectively write copy and make aesthetic choices through group conversations and democratic decision-making, and finalise the workflow design. Jacob Fox, a Masters student from De Montfort University who temporarily joined the project on placement, used the Project Builder tools to create the workflows that the volunteer researchers had designed, and uploaded the digitised images and input the project copy. Again, this was a task made easier by the previous sessions as the volunteer researchers had a clear vision of their project that was shared amongst everyone.

This division of labour reflected the interests and comfort level of the volunteer researchers, who were very interested in the opportunities provided by online crowdsourcing for engaging local and international communities but, even with training, were uncomfortable with the technical intricacies of using Zooniverse tools. We made the decision to provide assistance with this component of the work in support of the volunteers’ vision for the crowdsourcing project. This is a reality of co-creation: that at times project staff will need to step in and carry out supporting labour. In this case, we prioritised making sure that the volunteer researchers had final say in the project design and were able to translate their vision into a tangible product using the Zooniverse platform.

By enabling spaces for conversation and centring the needs and interests of the volunteer researchers throughout the project, we were able to ensure that they felt safe, supported, and above all, empowered to take such a hands-on role in this project. In post-project reflections of their participation, the volunteer researchers identified how this institutional support not only facilitated their participation in the project, but also gave them the confidence to learn new skills and apply them in a way that was meaningful and allowed them to achieve their personal goals for this research.

A workflow for volunteer digitisation

Heritage organisations are increasingly using volunteers to assist in collections digitisation projects, driven partly by limited internal staff resources to undertake the work but increasingly as a means of community outreach and engagement with collections. A critical component of a successful project is a thoughtfully designed workflow to bring genuine value to the digital outputs produced.

Too often, digitisation workflows are designed from scratch for each new project, increasing time, effort and cost. Our experience suggests that we can avoid these disadvantages by creating an overarching blueprint for volunteer digitisation projects with core elements that can be repurposed and reused as much as possible. Volunteer digitisation projects are often conceived by collections staff who have a great idea, but who may not have the skills to design and maintain workflows and the tools to support them. Having standard blueprints that can be followed enables consistency across projects and the authors hope that the toolkit here can offer such a blueprint to others.

For Communities & Crowds, the volunteer researchers used an Epson Perfection V850 Pro flatbed scanner for creating the image, a barcode scanner for entering metadata and Adobe Bridge and Photoshop for metadata entry and colour correction. Volunteer digitisation workflows vary in nature depending on the specific aims of the project. ‘One size’ rarely does fit all and they will usually need tailoring to the project requirements. When designing standardised and reusable digitisation workflows, a key challenge is building in sufficient flexibility to account for the inherent variability between projects. Attached here is the digitisation procedure we used for Communities & Crowds detailing each step of this process.

Workflow

A rigorously designed workflow is key to ensuring the desired outcomes and quality standards are met. When designing a digitisation workflow some fundamental principles to consider are integration, efficiency, quality assurance and customisation.

Integration: A digitisation workflow should be holistic and integrate all the different processes from the point the item is taken off the shelf to when it is placed back on the shelf. This can include inventory, cataloguing, rehousing, condition checking, locating, digitisation and ingesting content into a catalogue or collection information systems.

Efficiency: The workflow should be designed to make it as simple and efficient as possible. The fewer the steps, the quicker the task will be and the more likely to produce accurate and consistent outputs.

Quality assurance: Control measures for data and image quality should be built into the design to ensure the desired standards are consistently met via the workflow.

Customisation: The processes and the tools that support them should be able to be tailored to the specific requirements of the project.

Creating documentation workflows using AppSheet

Coming from a photographic archive, the materials to be processed by the Communities & Crowds project did not conform to the existing cataloguing standards used in SMG’s Collection Management System (CMS). The need to capture this non-standard information and the desire to present volunteers with a clear interface tailored to the specific requirements of the project informed our decision to use AppSheet, a no/low-code solution from Google, rather than, for example, a simple Excel spreadsheet, or cataloguing directly into the CMS.

The materials to be captured were predominantly photographs, part of a larger photographic archive, which is arranged with items of similar content collected into folders labelled by subject. As part of the digitisation process, materials would be individually numbered, barcoded and repackaged into new archival-grade storage. This means there were three distinct entities that needed information recorded about them: the items themselves, the folder they came from, and the new container in which they would be housed.[5]

For the items, we chose to record the following catalogue data: the item number, a newly assigned barcode, which folder they came from, their condition, any hazardous materials present, the picture agency, and a field for noting any issues of problematic language or image sensitivity in the photographs.

Before building the data capture tool, for each of these fields a decision was made about the type of field they should be (e.g. text, numeric, Boolean); what validation should be applied; what would a default value be if required; what values would be available to users if a picklist was required; were they mandatory and were they to be repatriated into the CMS at the end of the project.

The data capture solution that was produced from this specification gave volunteers a simple but powerful web app to capture information about the existing physical indexing of the materials, the future storage locations of the processed materials, and rich details about the items themselves, all in a format and structure that allowed for easy repatriation of the data into the organisation’s CMS.

A well-designed workflow application will assist in managing the workflow and support quality assurance throughout the whole process. An application should be designed to closely marry the physical processes of the workflow.

The nature of these kinds of projects – time bound and relatively small scale – may not warrant the organisation to invest in and build novel tools to support digitisation workflows. Often a low-technology solution is chosen – tools that are familiar, or that are on hand, that can quickly be deployed to achieve the desired results, such as an Excel spreadsheet. These can serve a functional purpose but may not always be the best solution.

The primary technology application used for collection management is the CMS. These systems often don’t support workflows well, though this is improving. And even if they do support workflows, there are challenges to opening up these systems to volunteers that include system complexity, access permissions, risk to data and training requirements.

There is a middle path between the Excel spreadsheet and a full CMS, which is to choose existing ‘low code’ technologies. There are many advantages, including low overhead for development so they can be built rapidly, prototyped, deployed and iteratively improved. Another advantage is that they can be tailored around the specific workflow, helping to streamline processes. Also, when tools are customisable and easy to use, intuitive applications can be built that improve usability and at the same time retain tight controls to enforce data quality.

Putting in place a clear process for managing the catalogue information needed for, and created by, a project should be one of the earliest steps in initiating a cataloguing or digitisation project, whether it is to be undertaken by paid staff or volunteers. If the information gathered is to be useful and have a life beyond the project, it must be clear how it relates to existing information, and how it will eventually integrate with that existing information. This reduces the chance the information will languish in spreadsheets, becoming increasingly difficult to access and manage after the project ends and the detailed knowledge of the project fades. Once it is clear what is to be captured, you then need to think about how best to capture it. Developing the data workflow alongside the physical workflow helps to ensure that solutions created are useful, rather than a hindrance.

Collaborative planning from the start means the needs of the physical and digital components of the project are balanced and the impacts of decisions in one branch are clear on the other. From the initial testing onwards, establishing a dialogue between end users and the builder(s) of the data capture tool ensures problems are identified quickly and refinements can be made. The result is a tool, and thus data, that is fit for purpose.

A data management checklist for community-led crowdsourcing projects

The concept of collaborative planning applies to much of the processes that make up Communities & Crowds-style projects, but particularly to digital resource management. These projects are creating not only new digital assets via the digitisation workflow but are also enhancing metadata for those new assets via online crowdsourcing workflows. This short checklist will provide a better sense of what kinds of collaborative conversations you should be having with institutional stakeholders before any new digital resources are created or enhanced.

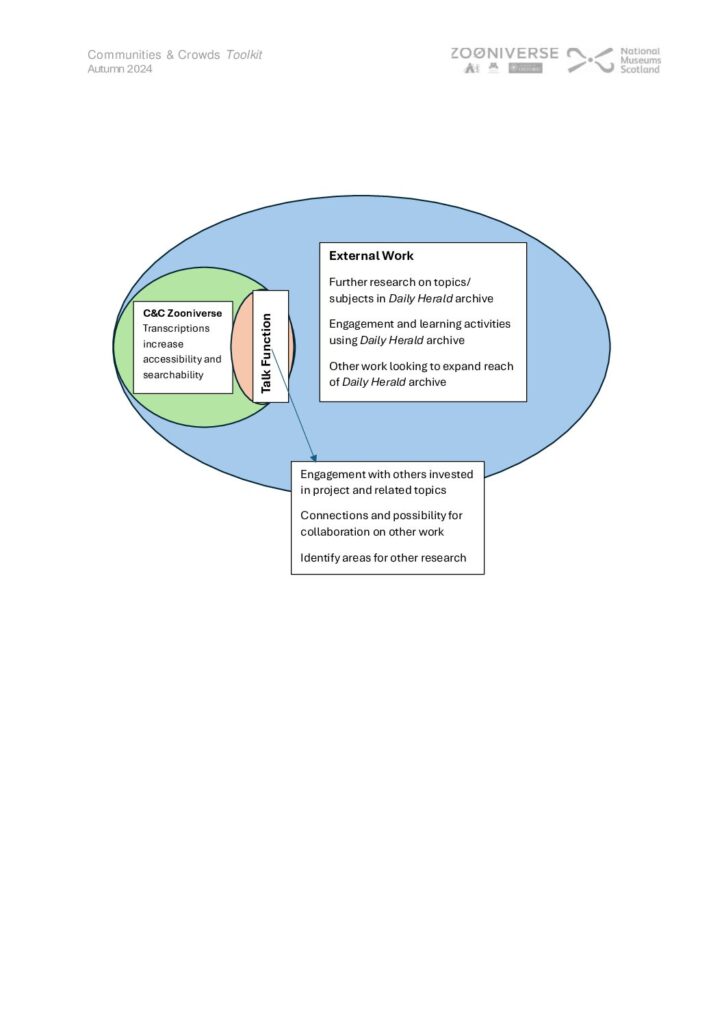

Translating community goals and digitised data into practical crowdsourcing tools

We developed two new Zooniverse tools in service of the Communities & Crowds project aims of better supporting GLAM-led crowdsourcing efforts and project participants. In this section, we will share short case studies about why we built these tools, how they work, and how they support this kind of project.

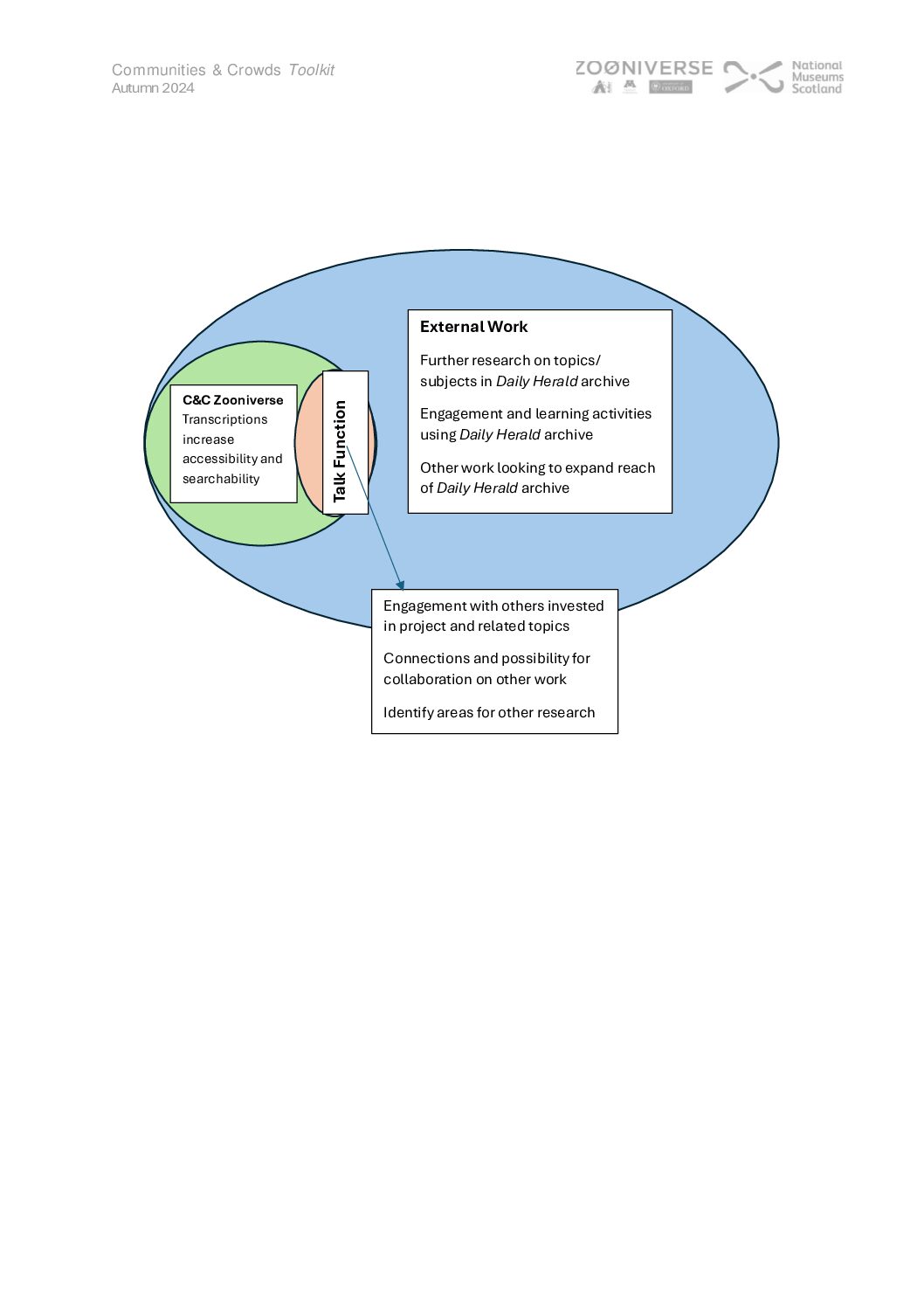

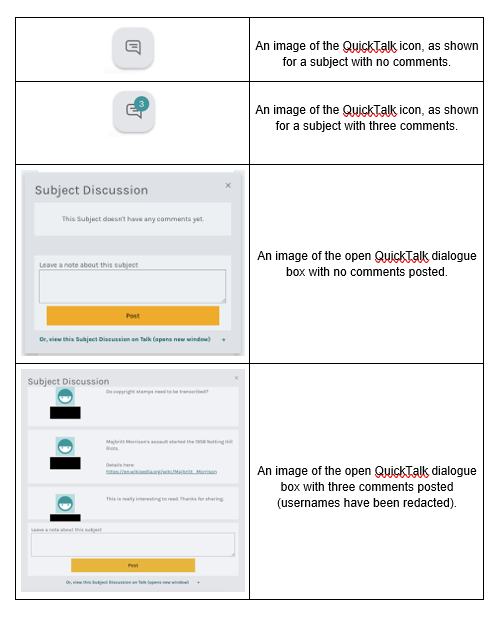

Using QuickTalk to encourage earlier sharing of volunteer expertise

All Zooniverse crowdsourcing projects come with a built-in message board system, known as Talk. The original design of the Zooniverse platform kept Talk interactions intentionally siloed from the classification interface; participants could comment directly on a specific subject, but only after completing the classification task. QuickTalk subverts this approach by integrating a ‘mini’ Talk area into the classification interface, allowing users to read and post Talk comments without leaving the page.

Project owners must opt in to using QuickTalk for their project; it is not enabled by default. As of writing, this feature is available only by request. Eventually, it will be an option within the Project Builder that teams can elect to ‘turn on’ for their project. We recommend mentioning the QuickTalk feature in the project tutorial, to remind participants that this feature is available for use. It can help to provide examples of what this feature looks like in multiple scenarios, so participants know what to look for and what each version of the QuickTalk symbol means.

QuickTalk supports Communities & Crowds-style projects by allowing participants to see and post Talk comments about the subject they are currently classifying. Participants often use Talk to do things like work out tricky letterforms or a specific author’s handwriting in a transcription project, and access to this information can be extremely helpful while completing the project task. Other examples include participants sharing additional research or information about the subject, which can be useful for the task, but also for a participant’s individual interest in, and engagement with, the project’s content.

Additionally, QuickTalk provides easier access to a project’s community, which can remind participants that there are other people out there working towards the same goal.

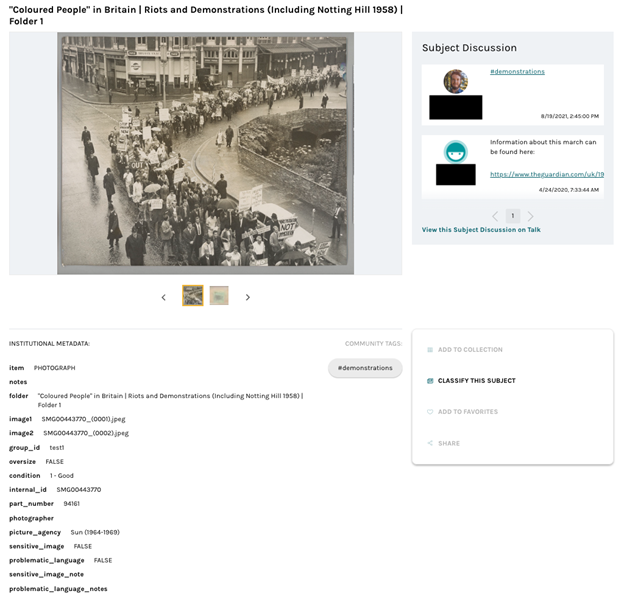

Surfacing volunteer-generated metadata via the ‘Community Catalog’

The Community Catalog (https://community-catalog.zooniverse.org) is a tool that we created to offer Zooniverse participants the opportunity to engage in the kind of archival exploration that the volunteer researchers in How Did We Get Here? found so compelling. However, one of the most impactful components of those archival sessions with the volunteer researchers was the conversations we would have about the photos in the archive, where they could share their experiences, memories and thoughts about the photos, the historical events depicted, and the importance of the collection. When we designed the Community Catalog, we wanted to create a digital space that would facilitate sharing and discovery of participants’ contributions alongside institutional information about the materials. The result was a data exploration app connected to individual Zooniverse crowdsourcing projects (How Did We Get Here? and Stereovision) that allows users to search and explore each project’s dataset based on participant-generated hashtags as well as institutional metadata.

The app includes a home page with search/browsing capabilities, as well as an individual page for each photograph included in the project. The subject page displays any available institutional metadata, participant-generated hashtags, and Talk comments. A ‘Classify this subject’ button allows users exploring the data to go directly to the Zooniverse project and participate in whatever type of data collection is taking place (transcription, labelling, generating descriptive text, etc.).

The work we have done on Communities & Crowds has made it clear that having access to all of a subject’s information in a single place is beneficial for project participants across disciplines, not just for GLAM crowdsourcing efforts. Therefore, the Community Catalog is not available for re-use by other projects in this exact form (i.e. as a standalone app), but, as of writing, the Zooniverse team is planning to incorporate many of the features of the app into the platform for wider use.

Creating a collaborative project via Project Builder

The process of creating an online crowdsourcing project featuring newly digitised materials will vary depending on the interests of your volunteer research team. Our experiences were very different between How Did We Get Here? and Stereovision, for example. In the former, the volunteer researchers were more interested in sharing the newly digitised images and communicating with local and global participants than they were with the technical and experiential design aspects of the process. With Stereovision the volunteer research team took to the design process very quickly and did not experience the same hesitation around the online component. Neither example is representative of the majority of volunteer researchers; there is no standard reaction or preference for individuals working on projects. Institutional staff members must therefore be prepared to adjust the amount of training or support time dedicated to project building depending on the interests and comfort levels of the volunteer research teams. In many ways, this is a good ethos for the entire Communities & Crowds approach to collaboration: the process must ultimately reflect the needs and interests of the participating communities.

For teams using Zooniverse to create their online projects, detailed resources for project building are available at https://help.zooniverse.org, including an in-depth Transcription Project Guide (https://help.zooniverse.org/transcription-project-guide/), which is aimed at teams working on creating projects with text transcription as the main goal, but which contains information that is broadly useful for any cultural heritage-focused projects. Higher-level project planning guidance is also available in The Collective Wisdom Handbook: perspectives on crowdsourcing in cultural heritage (https://britishlibrary.pubpub.org/), which is not Zooniverse-specific but as the name suggests includes a wealth of information specifically catered to cultural heritage-focused crowdsourcing projects. Our specific volunteer preparation methods and resources are available in the volunteer preparation and designing work sessions section of this toolkit.

Outlining financial practicalities

Though Communities & Crowds harnesses the donated labour of in-person and online volunteers, it is not cost-neutral. The financial components include staff time, software and physical equipment, which we have itemised below, being sure to highlight free software tools whenever possible.

1. Staff costs

Project management: Staff time is necessary to oversee the various components of the project. This can include grant writing, budget approval, staff supervision and ensuring that projects take place within any necessary timelines.

Volunteer supervision: This process requires staff supervision of, and support for, volunteer researchers. In our experience, this can be a single experienced staff member, but for inexperienced staff it would be preferable to work in a team or two or more, depending how many volunteer researchers the role is supporting.

Stakeholders: Additional staff may need to participate in decision making or offer support to participating staff members. These stakeholders may include internal data teams or digitisation teams, volunteer programme coordinators, and anyone with responsibility around communications and digital media.

2. Digitisation costs

Digitisation efforts where assets have not already been imaged require the use of a scanner and other physical equipment. For Communities & Crowds, we budgeted £2,000 for total digitisation costs. These included:

- Epson Perfection V850 Pro film and photo scanner: £810

- Motorola CS3070 barcode scanner: 2 @ £179ea = £358

- Object barcode label creation (outsourced to Abarcod for quality assurance): 5,000 @ £0.06ea = £300

- Object number labels (printed in-house): £200

- AWS cloud storage: £200

- PowerApps/AppSheet user licence: 2 @ £50/year = £100

The actual cost for digitisation was fairly close to our budgeted costs. It is important to note, however, that the cost of technology can change over time. For example, a V850 Pro scanner now costs closer to £1,000. Some of the above costs are also not always applicable for every team, e.g. if you choose not to use a barcoding inventory system. Equally, there are hidden costs here such as Adobe licences, as these were offered as core software within IT systems at both SMG and NMS. This is therefore a general estimate and should be understood as a guideline rather than a rule.

3. In-person meeting costs

Other costs to be considered are well-being and volunteer costs. We spent approximately £15 a week on tea, coffee and cake, which was a critical part of the volunteering sessions (see Figure 3 Workflow for Wellbeing). As part of SMG’s volunteering framework, volunteers are also offered reimbursement for travel expenses via public transport to attend in-person volunteer sessions.

Incorporating results of community co-produced projects in museums

The outcomes of the volunteer work at NSMM, through the Communities & Crowds project, has had impact not just on the collections, but also on the way stories are told in galleries. In Bradford, visitors want to see their memories and experiences of media technologies represented at the museum.[6]For cultural organisations, creating exhibitions that represent the myriad identities of people and places is a challenge, and one which risks further exclusions if communities do not feel included in exhibitions and programmes. It is imperative, therefore, that museums do not attempt to speak for ‘the community’ and instead offer spaces for self-definition and knowledge sharing (McGuire, 2023). The first Communities & Crowds project (How Did We Get Here?) invited conversation and critical enquiry into the Daily Herald archive. The next step for the museum was to incorporate this knowledge in the design and interpretation of its permanent galleries, to continue the dialogue about the role of media technologies in shaping attitudes about migration and identity.

Sound and Vision is a National Heritage Lottery funded project to create two new permanent galleries at NSMM.[7] The impetus to re-imagine these galleries has had a strong focus on the relationships between media and identity. The Daily Herald archive is an expansive source of inquiry for developing narratives about how people, places and communities have been represented by the media. However, the core challenge of engaging with the collection is that we often do not know who the people are within the Herald’s photographs. Engaging with narratives about community and migration requires a polyvocal approach to heritage interpretation (Abungu, 2023; Ashley and Stone, 2023), one which shares stories, told by multiple actors, to encourage visitors to reflect on how an object in a museum can speak to a variety of histories, presents and even futures.

In developing displays using the Daily Herald archive for the new galleries at the museum, we built on the polyvocality of the Communities & Crowds project to interpret how press images are used to construct understandings of identity. Through braiding individual volunteer responses to images of African-Caribbean people’s arrivals and experiences of Britain, the Sound and Vision galleries can encourage reflection on the multifaceted work that photographs provide. The volunteer interpretations will encourage visitors to consider how these images relate to the lived experiences of people in Bradford, and how images of the Windrush generation have been used and re-used by the media to create narratives about national identity which continue to shape the representation of Black communities in Britain today. Cultural memories of media are not fixed – they are highly mobile and always changing (Brunow, 2013). Therefore, through using the results of community co-produced projects in how the galleries interpret photographic collections, museums can hold space for conversations about identity not as abstract concept, but as lived reality rooted in how we see ourselves and our communities reflected in the images we consume on a daily basis.

Conclusion and call for adaptation

The case studies, workflows and templates in this toolkit are only a starting point. They describe the way that the volunteers and project teams who make up Communities & Crowds at both NSMM and NMS have been able to develop volunteer-led processes for creating new digitised assets of photographic collections which have resulted in online crowdsourcing projects that aim to answer the questions our volunteer communities are interested in.

The intention of this toolkit is that any institution with photographic collections can adapt these processes to their needs, and work with new audiences to tell stories relevant to them through institutional collections. The different workflows and processes are, however, in no way prescriptive nor do museum staff need to follow each step in the process. You may choose, for example, to follow only the in-person or online aspects of this process. An online-only example is the Zooniverse project Bradford’s Industrial Heritage in Photographs, which was developed by Alex Fitzpatrick as part of a larger project which included testing the potential of the QuickTalk function described earlier.

We have described a holistic process, which begins and ends with volunteer agency and choice, because it has demonstrated greater engagement and volunteer satisfaction than in-person volunteering alone (see Focus Group Reports). However, the goal is for any other community or institution to decide what is right for them, and to use any part of this toolkit as needed.

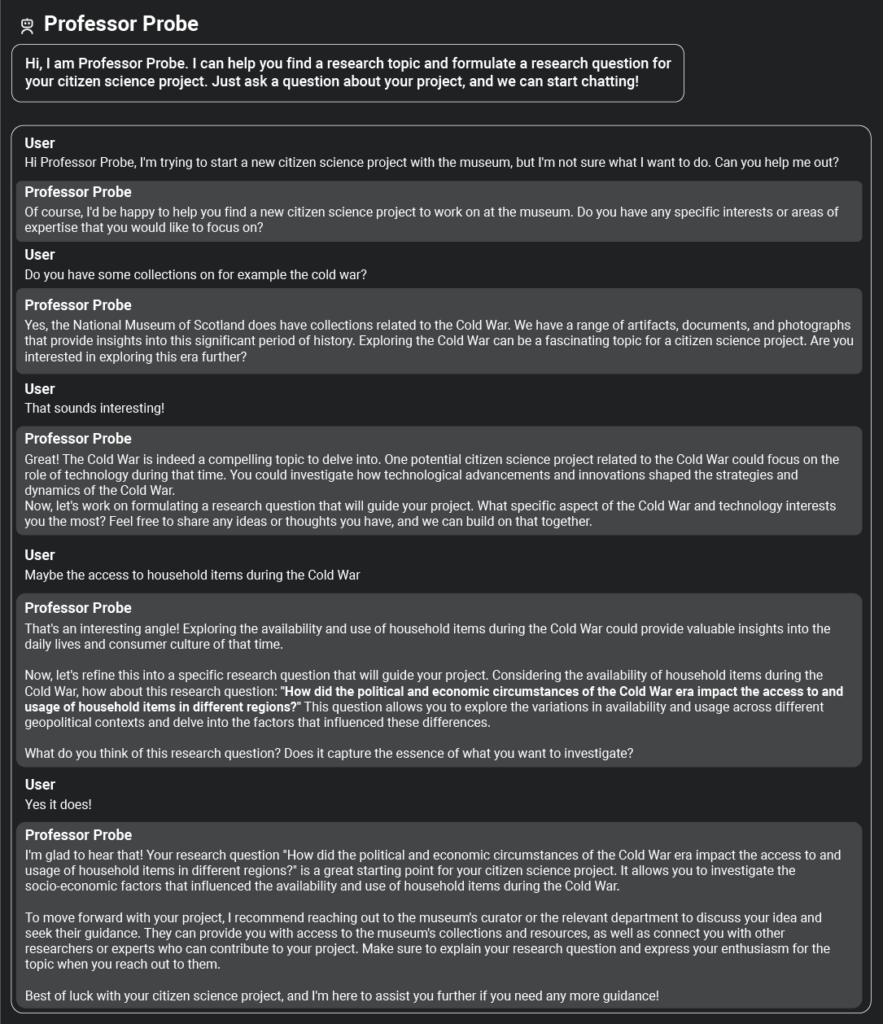

We also hope that the process of undertaking PAR-based volunteer collaboration leads to new relationships and projects which are based on a set of shared values rather than photographic digitisation and crowdsourcing per se. One example of this is the collaboration with Paulien ten Hagen, who was inspired to create a ChatGPT design experiment based on the Communities & Crowds project as part of her MA dissertation focused on citizen science, a form of crowdsourcing focused on participatory science research.

Paulien describes how she started her project by framing a question: ‘Are you interested in exploring how to give people who volunteer a voice?’ Because this is an extensive question for a thesis, it was narrowed down to: ‘How can you give volunteers a voice in citizen science projects?’ The research began by looking into citizen science and the volunteers. Finding out what drives these volunteers in their work is valuable because the design must resonate with them.

Giving volunteers a voice meant including them more intensively in a citizen science project. Paulien wanted to shift from a collaborative to a more co-created citizen science project. The design aimed to involve the volunteers in the earliest stages, like choosing a topic and formulating a research question for a new project.

This led to the following design concept: a virtual museum research assistant, Professor Probe. Professor Probe is an online chatbot whose goal is to help you, a volunteer, discover a research topic that fits within your interests, and help with formulating a good research question (Figure 9). All of this is done while keeping in mind that the project should be relevant to the museum as well. The aim is to make the volunteers feel confident in what they want and expect from a project when they volunteer at the museum. This tool is ultimately aimed at making any new citizen science project a collaboration between the museum and the volunteers. While Paulien’s work here is a design concept, not a finished product, it demonstrates how the ideas from this toolkit can lead to all manner of outputs focused on volunteer agency and voice, even if some of them are quite different from the projects produced through Communities & Crowds.

This set of tools and workflows are now yours to recreate. Reiterate, redesign, reuse and share with your own communities and collections.