Inventor, devoted daughter, or lover? Uncovering the life and work of Victorian naval engineer Henrietta Vansittart (1833–1883)

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505

Abstract

This article focuses on the life and work of Victorian naval engineer Henrietta Vansittart (1833–1883), who designed and patented the Lowe-Vansittart propeller, a model of which is held in the Science Museum collections. Vansittart is a rare example of a woman who practised as an engineer in nineteenth century Britain, yet hitherto she has not been the subject of extensive academic research. This article contributes to wider efforts to recover the multifaceted roles that women have historically played in engineering, which have often been obscured or overlooked.

Using a range of primary sources, including a pamphlet written by Vansittart that is held in the Science Museum Library, alongside newspaper articles, contemporary engineering literature and personal letters, this article seeks to uncover what we can learn from her life and work. It will explore available routes into engineering for women in this period, when formal education and training opportunities were not open to them, and discuss how a woman in engineering could frame herself in this context. For Vansittart, her father’s engineering work was the vital access point to engineering. She did not receive a formal education, so it was through him that she informally learnt about the technicalities of screw propellers. This article will demonstrate the importance of family connections for women generally to enter into the field of engineering and reveal the ways in which Vansittart in particular used familial legacy to construct her position as an engineer, helping her to eschew prevalent gender norms. The article will also question why we do not know more about Vansittart’s career, by exploring the complexities of her personal life and how this may have impacted on her legacy.

Keywords

Henrietta Vansittart, nineteenth century, propeller design, women in science and engineering

Introduction

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/Finding objects in STEM-related museum collections that directly relate to women can be a challenge, thus it is worth taking notice when objects of this kind are located.[1] One such object is the model of the Lowe-Vansittart screw propeller blades held in the Science Museum collections. The model was made in 1869 by Henrietta Vansittart (1833–1883) from wood and paint, and she herself donated it to the Museum in 1874 (Anon, 1889).

The Museum’s description of the object states that the screw propeller blades were designed and fitted by Vansittart for trial on HMS Druid in England in 1869.[2] Reporting on these trials, an article in The Times from the same year stated that in comparison to older screw propeller designs ‘the Lowe-Vansittart has unmistakably shown its superiority’ (Anon, 1869c, p 10). The propeller was widely used in the Royal Navy’s ships and was awarded a first-class diploma at the Kensington Exhibition in 1871, as well as winning awards across the world. Thus the Lowe-Vansittart propeller was recognised as a success by contemporaries, propelling ships in a manner that was faster, more efficient and with less vibration (Anon, 2020). Arguably the propeller itself was a relatively minor moment in naval engineering history; but that its inventor was a woman is remarkable. Who was the woman behind this invention? And in a period when it was very rare to find women practising as engineers, how did she become a recognised inventor?

This article seeks to discover more about the life and work of Henrietta Vansittart (née Lowe),[3] who designed and patented the Lowe-Vansittart propeller. Vansittart is an unusual example of a woman who practised in engineering in the mid-nineteenth century. Born at a time when education for girls was limited, Vansittart gained her engineering knowledge through her father, James Lowe (1798–1866), a manufacturer of smoke jacks and an inventor, who patented screw propeller designs. After his death in 1866, she continued his work on screw propeller design, finding success in her own right, while continuing to teach herself and experiment. Before her untimely death at 50 years of age in 1883, she obtained patents for the Lowe-Vansittart propeller in various countries, delivered public orations on the topic, won awards, and travelled to exhibitions and fairs across the world. Her personal life was no less unconventional for a woman of the time. On 25 July 1855 she married Frederick Vansittart, a lieutenant of the 14th Dragoons, at the British Embassy in Paris. Four years later, in 1859, she began an affair with MP and novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873), a connection which lasted until 1871 (O’Mahoney, 2012). Despite her public successes as an engineer and patent holder, relatively little is known about Vansittart. Other than highlights in collected studies (see, for example, Stanley, 1993, p 338; and Cropley, 2020, pp 115–119), an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB) and a variety of online blog posts, there is no previous dedicated academic study of her position as a woman working in engineering in nineteenth-century Britain.[4]

In recent years, the varied role women have played in engineering has started to receive sustained attention, with projects like Electrifying Women: Understanding the Long History of Women in Engineering (AHRC/University of Leeds, 2019/20). The centenary project of the Women’s Engineering Society (WES), which was founded in 1919 to protect women’s jobs in engineering fields after the First World War, has led to greater knowledge of the various women who made careers for themselves in the early twentieth century, as well as the pioneering women who came together to form the Society (see Heald, 2019). A combination of factors, including better access to formal education, the opportunities afforded women by the First World War, and the arrival of greater political rights meant that there was a dramatic increase in women in various engineering fields. In the first half of the twentieth century there are numerous examples of women who had long, highly successful careers in engineering, such as Margaret Partridge (1891–1967), Verena Holmes (1889–1964), Hilda Lyon (1896–1946) and Beatrice Shilling (1909–1990).

In the previous century, this was not the case and there are few examples of women in engineering that we know about. Electrical engineer and physicist Hertha Ayrton (1854–1923) is perhaps the most well-known example (see Bruton, 2018, in Issue 10 of this journal), while Sarah Guppy (1770–1852) – the first woman to patent a bridge – is an important forerunner from the Georgian era (though arguably also in need of further academic attention).[5] When access points to engineering were so limited for women in the mid-nineteenth century, it begs the question: how did Henrietta Vansittart become an exception? As one of the few known examples, Henrietta Vansittart’s pathway into engineering can offer us a perspective on how it was possible for a woman to gain skills in engineering. Her life and work can also provide us with insight into what the working life of a woman in engineering in this era looked like, including the ways in which a woman engineer chose to present herself and her work, as well as the constraints she faced. In doing so, the article expands on recent historical scholarship, which is complicating the notion that men and women inhabited separate spheres in Victorian Britain, with women confined to the domestic and men operating primarily in public, political spaces (Vickery, 1993; Gleadle, 2017). As an example of a married woman operating in a predominantly masculine sphere, with a public persona beyond the domestic, the case study of Henrietta Vansittart provides further proof of the varied ways women operated across both these spheres. Finally, given the unusual nature of Vansittart’s life and work – and the scarcity of comparative examples – there is a further question to be considered: why do we not know more about this example of a woman practising openly as an engineer in the Victorian era in Britain? In considering this question, the article will open up discussion of the manner in which legacies for women in engineering have been recorded, forgotten and obscured.

As previously stated, this research forms part of a wider effort to locate the stories of women in engineering, many of which had been historically side-lined or erased. An early example of this kind of research was the pioneering, cross-European study of women in engineering Crossing Boundaries, Building Bridges (Oldenziel, Canel and Zachman, 1999), which helped to trace the varied contributions of women across different countries and timeframes. Recognition has been given to individual women’s successes in the field, such as Hertha Ayrton, credited with being an engineer, mathematician, physicist, patent holder and suffragette (Bruton, 2018) and less visible women, such as Blanche Thornycroft (1873–1950), who played a crucial but unrecognised role in her family’s naval business located on the Isle of Wight (Harcourt and Edwards, 2018). There has also been some attempt to collate the various patents filed by women to demonstrate the many inventions women created (Jaffé, 2003).

The importance of women to technological change, particularly in the domestication of electricity, has been highlighted in Graeme Gooday’s (2008) work on that subject. Gooday draws attention to the importance of looking at familial links to find out about the role played by women, identifying three spousal collaborations that aided the domestication of electricity (ibid). The United Kingdom’s Women’s Engineering Society has received less academic attention than might be expected, though Carroll Pursell (1993 and 1999) has written on the subject as well as the associated organisation, the Electrical Association for Women. Clare Wightman (1999) has charted the multifaceted contribution of women to the engineering industries beyond the wartime work they are famous for. More broadly, there has been an effort to locate women in the history of the sciences, reinstating them back into a narrative they have largely been written out of (Barrett, 2017; Fara, 2018; Jones, 2019).

Methodology

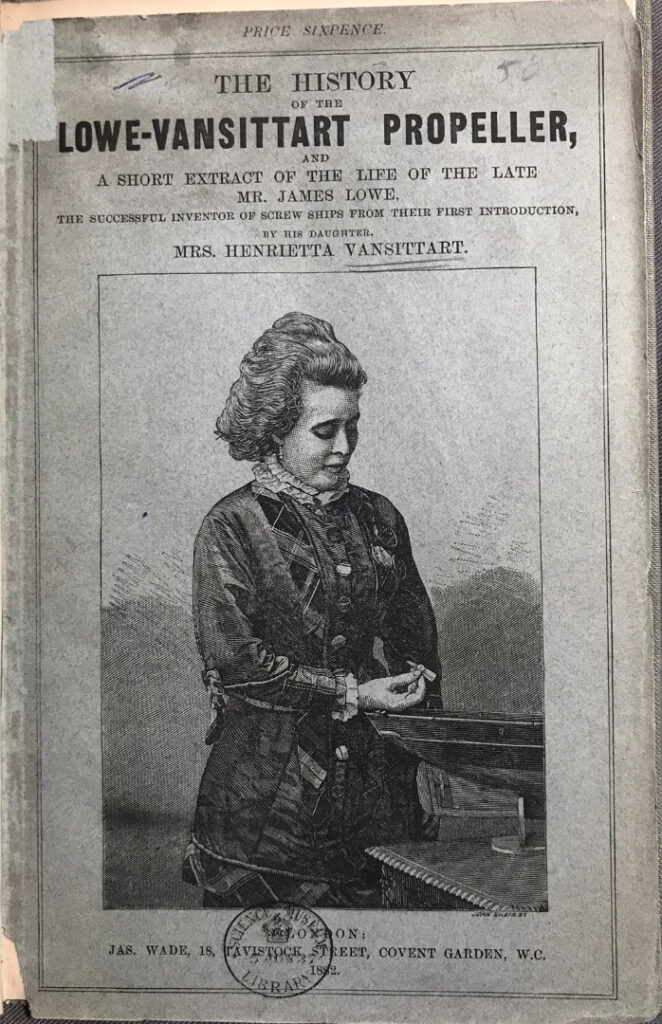

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/002In order to uncover the life and work of Henrietta Vansittart, a range of archival research has been undertaken, not only to locate Vansittart’s engineering work, but also to try to reveal her voice and agency. Such an approach builds on the aforementioned revisionist histories of women in the nineteenth century that have sought, as Kathryn Gleadle describes it, ‘to understand how women themselves interpreted, judged and perceived their capabilities’ (Gleadle, 2017, p 5). These new histories have looked for evidence of how women have overcome barriers to find means for their own ‘assertion and fulfilment’ (ibid). A pivotal source for such an approach, providing biographical information and illustrating her engineering achievements and her commitment to continuing her father’s work, is the pamphlet written by Vansittart herself, titled The History of the Lowe-Vansittart Propeller and a short extract of the life of the late Mr James Lowe, the successful inventor of screw ships from their first introduction. This small book was published in 1882 (one year before her death) by Jas Wade in London and sold for six pence. A copy of the pamphlet was gifted to the Science Museum by R B Prosser and is accessible via the Science Museum Library.[6] The pamphlet contains a transcript of the paper Vansittart delivered to the London Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsmen on 1 April 1876, as well as two shorter public orations she gave, testimonies about the Lowe-Vansittart propeller, a copy of its patent information, and correspondence.

The pamphlet contains much of what is known about Vansittart’s life, including the only verified image of her (see Figure 2).[7] There are certain inaccuracies in it; for example, Vansittart claims she is born seven years later than she was (her real birth date is shown in census data). The pamphlet is written by Vansittart herself, so should be treated with caution – it is her own version of her father’s work, her work, and her life, so we have to interrogate her motives as its ‘narrator’. However, this is also what makes it so fascinating; it is her own narrative on her legacy as an engineer.

Newspaper archives have also proved a useful means to trace Vansittart’s work and provide evidence of the discourse around it. Seven reports were made on the Lowe-Vansittart propeller and its trials in The Times newspaper in the ‘Naval and Military Intelligence’ section between 1869 and 1873. These newspaper reports provide evidence of the ways Vansittart’s engineering work was received and recorded and they help to verify the claims she makes in the pamphlet about the propeller’s success. Contemporary engineering literature – such as the Society of Engineers journal – and catalogues from museums and exhibitions provide further insight into the reach of Vansittart’s work. The literature, in particular, helps to show how the Lowe-Vansittart propeller was situated in contemporary debates about means of ship propulsion.

The surviving letters that she sent to her lover Edward Bulwer-Lytton, held in the Bulwer-Lytton archives at the Hertfordshire County Council Archives, offer a different insight into Vansittart’s life.[8] These tell us about her personal life, offering another layer of information about her personality, her motivations, and the way she expressed herself. Content from the letters also provides contextual information on her work as an engineer and the ways she financed those endeavours. Additionally, it was possible for the author to access Vansittart’s notes from the Newcastle asylum – St Nicholas Hospital, Gosforth – where she died in 1883, from mania and anthrax, an infectious disease caused by bacteria.[9] Though these notes do not necessarily offer much insight into her life, they do confirm the tragic nature of her death and detail how she spent her last few months.[10]

Vansittart’s route into engineering

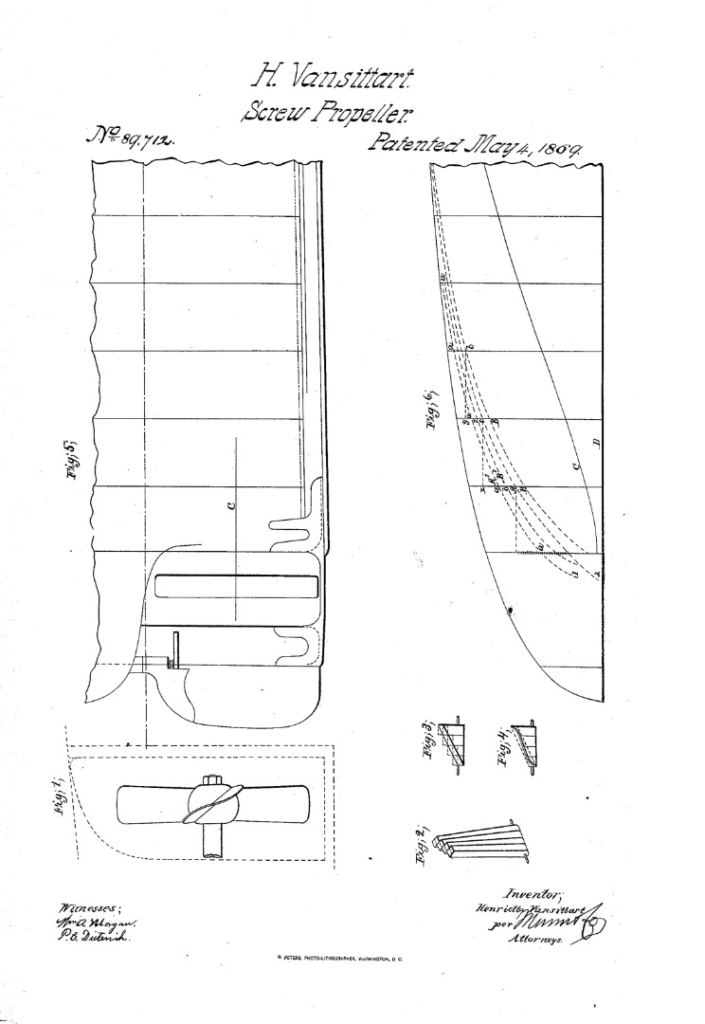

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/003As already discussed, as a woman who held patents in several countries (see Figure 3), who published on her engineering work and spoke publicly on the subject, Henrietta Vansittart is exceptional for her era. It is thus of value to consider how she gained her engineering knowledge, how she entered the field, and the extent to which this bears resemblance to how other women found a route into engineering pre-1914.

Henrietta Vansittart was born in 1833 in Ewell, Surrey, into a family of builders and inventors, with upwardly mobile connections to the Seymours of Syon House (O’Mahoney, 2012). Unlike later examples of women engineers and scientists, such as Hertha Ayrton, Vansittart was born too early to benefit from many of the educational reforms that were brought in over the second half of the century. For example, Girton College, the first college for women at Cambridge University, was founded in 1869. In 1871, the National Union for Improving the Education of Women was created to campaign for the provision of better educational opportunities for women. There were some changes in the 1840s that could have made a difference, including the creation of Bedford College, London in 1849 – the first higher education college for women – but the evidence suggests that Vansittart did not receive a formal education (O’Mahoney, 2012). Indeed, as was the case for many girls, her education took place largely within the family (McDermid, 2008, p 91). What was more unusual for the time was that the education she received was in engineering from her father, rather than the pursuits then deemed suitable for girls, such as basic literacy, history and geography, alongside music, languages and painting, which were usually taught by a governess (Gleadle, 2017, p 53).

It is perhaps even more curious that this education with her father continued after Vansittart’s marriage in 1855; two years later she was aboard HMS Bullfinch for trials of her father’s screw propeller (O’Mahoney, 2012). In the mid-1800s, the designated place for married women was seen to be within the marital home. As Kathryn Gleadle explains:

Within the ubiquitous nineteenth-century discourse of separate spheres, women were portrayed as financially, intellectually and emotionally dependent upon their male kin. They were encouraged to perceive themselves as ‘relative creatures’, whose path in life was to nurture the family and to provide unstinting support for the head of the household (Gleadle, 2017, p 51).

Though still arguably supporting her kin, by continuing to accompany her father in his engineering work, rather than transferring all her attentions to her new husband and his household, Vansittart was not operating in line with societal expectations (and we shall see later that her long-term extra-marital affair was a further way in which she transgressed societal norms).

Conventions aside, Vansittart’s description of her engineering training, as described in her 1882 pamphlet, reveal that her familial connection was crucial to her training in engineering. She describes how her father, James Lowe, educated her in screw propeller design in particular. Lowe patented his own design for a screw propeller in 1838 (patent No. 7599), which sought to improve on propeller design by means of a screw of one or more curved blades, which was fixed on a revolving shaft below the waterline of the vessel (Boase, 2011). However, he was only one of many inventors who had proposed designs in the early nineteenth century for screw propellers, with a large amount of trialling and experimentation happening at this time. F P Smith (1808–1874) and John Ericsson (1803–1889) are both generally recognised as the key innovators of screw propulsion, but there were several dozen more inventors working in the field (ibid).

Engineering literature from the nineteenth century indicates that there was an active debate about the progression of screw propeller design and innovation. For example, John Bourne’s A Treatise on the Screw Propeller, With Various Suggestions of Improvements (1855) is adamant that Lowe’s patent for the propeller was not original, and that it had not ‘contributed in any measure to the practical introduction of the screw propeller’ (p 93). Later literature offers a more generous view of Lowe’s work, such as George C V Holmes’ Marine Engines and Boilers (1893), which credits both Lowe and Vansittart for advancements in ship propulsion (p 102).

In fact, in 1844 Lowe brought action against an engineering firm in Greenwich for infringing on his patent. It was decided that while Lowe was not the original inventor of the screw propeller, he had created a unique combination of them, which had never before been applied to ship propulsion (Boase, 2011). Despite this ruling, and some initial success with his propeller design, which was fitted in a few government ships, James Lowe’s life ended in an impoverished state. His entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography states:

On 19 August 1852 Lowe took out another patent, No. 14263, for his propeller. He apparently spent his wife’s fortune of £3000 in his experiments, reduced himself to poverty, and never succeeded in obtaining any compensation for the use of his invention. On 12 October 1866 Lowe was run over by a wagon in Blackfriars Road, London, and killed (ibid).

The hardship of this time made a deep impression on Vansittart, who wrote of it: ‘My parents passed through years of sad and lamentable hardship; indeed all the surroundings are so painful that I have not the heart to put them to paper’ (Vansittart, 1882, p 17).

There is little surviving evidence to show exactly what she learned from her father, but in her paper to the London Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsman, Vansittart describes accompanying her father on the screw propeller tests aboard HMS Bullfinch in 1857:

[The propeller] was fitted to H.M. Gunboat Bullfinch in 1857, and I was present with my father on board that vessel. We had various trials, and he was desirous of trying the blades at different angles… (ibid, p 8).

We know enough of her subsequent work, however, to assume that what she did learn from her father allowed her to continue working on his invention after his death, which she patented in 1868 as the Lowe-Vansittart propeller.

While Vansittart’s family-based education in engineering may have been unusual for a young woman in the mid-nineteenth century, it was not necessarily that exceptional for a woman in engineering in later decades. Indeed, as more research is conducted in this area, the role of family in training and education for women engineers is beginning to emerge as a key theme, especially before more formal educational opportunities were opened up after the First World War and the greater provision of education for women generally.[11] The same is not true for all subjects and occupations: in the Victorian era there was a general trend towards women participating less in family business, as working and domestic spheres became (at least notionally) more separate (Davidoff and Hall, 1987), but the field of engineering appears to be one area where family connections had a large role to play in introducing female family members to this arena.

Recent research by Keith Harcourt and Roy Edwards (2018), for example, has brought to light the contribution of another naval engineer, Blanche Thornycroft, who played a pivotal role in her family’s engineering business on the Isle of Wight, and provides a useful point of comparison to Vansittart’s career. Evidence of Thornycroft receiving a formal education is also scant and it is likely that she gained her experience through working in the family business. Her father Isaac acted as her mentor, and she was described as his ‘devoted assistant’. Though a very private figure, her notebooks reveal the role she played in many of the businesses’ major developments and she did become a female associate of the Institution of Naval Architects in 1919 (Harcourt and Edwards, 2018). Thornycroft is an example of the way that women’s contribution can be hidden within the various roles of a family business. The case of Vansittart is somewhat different. Her father was effectively a lone practitioner, not the head of a family business, and after his death, in continuing his work, she also worked alone. Indeed, her own reporting of her work on the screw propeller is emphatic on this point: ‘I hope that the Admiralty and manufacturers and shipowners may award me according to my work, the whole of which has been done by myself and has reduced my capital’ (Vansittart, 1882, p 19).

Another woman in a somewhat similar situation was Rachel Parsons (1885–1956), who had both family connections and access to a formal education. She was introduced to engineering through her parents, Charles and Katharine Parsons, of Newcastle-based engineering firm Parsons & Co. She went on to study Mechanical Sciences at the University of Cambridge and co-founded the Women’s Engineering Society, alongside her mother, in 1919 (Heald, 2019). For various reasons, Parsons abandoned her engineering work and, like Vansittart, died tragically.[12] Anglo-French automobile engineer Dorothée Pullinger (1894–1986) was also introduced to engineering through a parental company and has recently received academic interest.[13] Like Vansittart, Pullinger received much of her engineering education from her father Thomas Pullinger (1867–1954), an automobile engineer. Together they founded the Galloway Engineering Company and built the Tongland factory, which was a major employer of women in the south-west of Scotland in the early twentieth century (Clarsen, 2003, p 335).

Thus, Vansittart can be viewed as an early example of a wider trend for how women were introduced to engineering, providing further evidence for the contention that family connections were a key factor in engineering education for women before more formal opportunities emerged.

Devoted daughter

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/004Although we can situate Vansittart’s entry into engineering via familial connections within a larger picture of how women accessed the field, living in an era of increasingly segregated and binary gender ideals, we can surmise that she had the potential to be exposed as a woman practising alone in a male-dominated field. Furthermore, her marital status also had the potential to complicate matters. While it may have been more understood that single women had to find work out of necessity, or that widows had to continue a husband’s work to support her family, a married woman was not considered to need to work nor was there seen to be a place for her within the ‘public’ sphere of politics and commerce. It is pertinent, therefore, to evaluate the ways in which Vansittart framed herself and her engineering practice to make it appear acceptable to societal norms. Here, her father was again integral. Vansittart continually presented her work as a means to preserve the legacy of her father after his death and defend him against his detractors. In this way, her endeavours were not necessarily the same as paid work – which would have been deemed suspect for a married woman of her social standing to hold – but instead in line with the various ways women engaged in social work, domestic labour, estate management and work in family businesses without being paid or officially recognised as workers for the preservation of their husband’s household and familial legacy (Gleadle, 2016, p 51). As a result, we might consider how Vansittart created a role of ‘devoted daughter’ for herself, rather than asserting her own identity as an engineer or inventor, as a way to classify her work as outside the boundaries of employment and within the domain of familial service.[14] Within the available evidence, there are several instances where Vansittart records her devotion to her father, frequently presenting her work in relation to him.

Evidence of this can also be found in how James Lowe was buried and memorialised. In the copy of Vansittart’s 1882 pamphlet held by the Science Museum collections, a newspaper cutting from 1905 about the invention of the screw propeller has been pasted in,[15] which recalls the engraving on James Lowe’s tombstone:

Sacred to the memory of James Lowe, Esq., who was born May 13th 1798 and met his death from an accident on the 12th October 1866. He was the Inventor of the Segment of the Screw Propeller in use since 1838 and his life though unobtrusive was not without great benefit to his country. He suffered many troubles but bore them lightly as his hope was not of this world but in our Saviour. Erected by his sorrowing Widow and his affectionate daughter, Henrietta Vansittart.[16]

Vansittart’s inclusion by name as the last words on her father’s tombstone (which she erected) shows the importance she placed on their relationship and indicates that it is something she wanted other people to see. Her mother, in contrast, is not named. The plaque acts as a means to promote her father’s achievements to visitors to the grave, naming his invention, and emphasising both his contribution to his country and his ability to endure many hardships. The need to defend her father might have emerged from the court cases he was involved in concerning the patent of his screw propeller, and was perhaps also due to the fact that Lowe’s passion for inventing had reduced the family to poverty (Boase, 2011).

Vansittart’s pamphlet shows more evidence of her desire to promote her father’s work. The title alone indicates the purpose of the publication: The History of the Lowe-Vansittart Propeller, and a short extract of the life of the late Mr. James Lowe, the successful inventor of screw ships from their first introduction. The inclusion of the qualifier ‘successful’ suggests that this is, once again, a defence of Lowe’s work and a chance to prove his detractors wrong.

We know, however, that the improvements made by Vansittart on her father’s propeller worked more successfully than the original, yet this is not a factor that Vansittart sought to highlight. Working on, and promoting, her father’s screw propeller was for Vansittart a matter of family legacy not about her own engineering ambition. It is a topic she corresponded with her lover Edward Bulwer-Lytton about. In an undated letter to him, she laments that a member of the Admiralty is making experiments with her father’s propeller invention from 1855, without fully understanding how it works, stating that ‘it is quite cruel’ and referring to her ‘poor father’.[17]

In order to defend her father’s work, and make improvements on it, Vansittart was willing to speak in public and correspond with various people, developing a public persona as a woman in engineering (even if that was not how she presented it). A short speech Vansittart gave in 1880, printed in the 1882 pamphlet, helps to explain her motivations in regard to this:

A young lady in this gallery has asked me to speak about women’s rights; I have no doubt that she wishes to know what my opinion is on the subject. Well, it is, that women have their rights, and that their rights are in their homes […] It was the woman who was made free, therefore my sex are freed from bondage […] but mark me well, ladies, should you be called forth in spirit to vindicate a late father’s cause, or a mother’s, sister’s, or brother’s, flinch not, but come forth with the talents given, and take the shield of faith and sword of truth, and falsehood and fraud will be made to flee from the presence of truth and its touch (Vansittart, 1882, p 28).

In her own words, Vansittart reveals that her work in engineering was not driven by the idea that women are meant to be in the working sphere – on the contrary she states that she believes that their place is in the home – but by a conviction that women should vindicate a family member’s cause if needed. Her views, therefore, appear to be in line with the prevailing ideas about separate spheres for men and women. She explains earlier in the pamphlet that this speech she delivered as ‘the toast of “The Ladies”’ was one of only three times she had spoken publicly, the first two being in service of her father (Vansittart, 1882, p 3). Indeed, it was very rare for any woman at all to speak publicly on scientific and engineering matters in this era. According to her obituary in the Journal of the London Association of Foreman Engineers and Draughtsmen, ‘Vansittart was the only lady, it is believed, who ever wrote and read a scientific paper, illustrated by diagrams and drawings made by herself, before the members of a Scientific Institution’ (quoted in O’Mahoney, 2012). We see then the strength of Vansittart’s conviction that when a matter concerned one’s family, it was a woman’s duty to leave the domestic sphere and speak publicly. Nevertheless, Vansittart’s short speech can be viewed as an example of how a woman justified eschewing social conventions to fulfil her own objectives, rationalising and moving beyond binary gender-based codes of conduct to do so.

Vansittart’s position as a devoted daughter can be compared to the ways in which the spouses of engineers framed their contributions to their husband’s work. Marriage, like family businesses or trade, was one of the available routes for women to access engineering. Katharine Parsons (1859–1933), wife of Charles Parsons (1854–1931), is one such example. According to a profile of her in The Woman Engineer, she accompanied her husband on trials of his underwater self-propelled torpedo devices on the lakes in Roundhay Park, North Leeds, including shortly after her honeymoon (Anon, 1940). She too developed a public persona, as one of the founders of the Women’s Engineering Society, giving speeches before professional bodies on the issues of women’s work, such as a speech she gave in Newcastle in 1919. Graeme Gooday’s (2008) research into electrification revealed the importance of engineering spouses for the introduction of electricity in the late nineteenth century. Alice Gordon (c. 1855–1929), for example, wrote of her experiences as an engineer’s wife, revealing her engineering knowledge and appreciation, when describing the electrification of Paddington Station in London (Gordon, 1891, pp 153–171).

Consequently, rather than appearing to threaten the established norm for men and women to inhabit separate spheres, women instead constructed models of the devoted spouse or daughter, which, while configuring their work in relation to men, allowed them to pursue their interests and objectives. Vansittart, however, is also interesting for her deviance from this model. She was a married woman, but while using similar tactics to frame her contributions to engineering as other married women used in the latter half of the twentieth century, her engineering work was not actually connected (as far we know) to her husband. The other comparative examples of women in engineering explored thus far mostly divide into two categories: married women assisting their spouses, or unmarried women working within family businesses. Vansittart does not fit neatly into either category, but rather she straddles both.

An accomplished engineer

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/005Despite the manner in which Henrietta Vansittart positioned herself – as a devoted daughter honouring her dead father – she was an accomplished engineer in her own right, who achieved material success in her lifetime, including filing patents, winning awards, and the fitting of her updated screw propeller on government ships. The pamphlet she published contains an array of information about the work she did and her engineering knowledge. Furthermore, as the material in it was assembled by Vansittart, it shows how she chose to frame her own work as an engineer. While she clearly positioned herself as a devoted daughter, she was also keen, when necessary, to establish the success of her work on the updated propeller, demonstrating the support she had from the Admiralty and other engineers, and entering into contemporary debates about ship propulsion.

The first instance where Vansittart presents herself alone, in direct relation to her invention, is in the image on the frontispiece of the pamphlet, where she is holding a small model of a propeller (presumably the Lowe-Vansittart), situated next to a model of a ship (see Figure 3). This is the only verified image that we have of Vansittart. She looks demurely down at the propeller model, with her eyes lowered, suggesting humility. Yet the fact that she is holding the propeller implies ownership over it; her hand is the maker of the propeller, and her gaze towards it illustrates her focus on it and her command over it. On the frontispiece, the most outstanding text, after the name of the propeller, is ‘Mrs. Henrietta Vansittart’, not James Lowe. Images of women in engineering are unusual, so this presumably self-commissioned portrait of Vansittart offers us a rare representation of a woman in the field. It provides evidence of how the pamphlet was not only securing her father’s legacy, but also writing the story of her engineering work, emphasising her own agency in this.

That Vansittart had extensive knowledge of the engineering behind her father’s 1838 propeller design (and the two subsequent versions of it, from 1852 and 1855) is demonstrated in the paper she read before the London Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsman, which is printed in the 1882 pamphlet. Here Vansittart describes the hands-on experience of propeller testing she received from her father. The paper also reveals her technical expertise in relation to propellers and her ability to write on the subject with authority. However, this is expertise that she chooses to efface in her opening remarks, perhaps to assuage any doubts there might be about her in relation to her gender. She begins the address by stating:

[I hope] that it will not be expected of me that I should be as expert in the discussion of scientific matters as the gentlemen who make it their business to lecture upon such subjects as screw propellers and their shafts (Vansittart, 1882, p 3).

She proceeds to clarify what knowledge she does have by explaining that she is aware of the engineers working on propellers and that she has attended two talks on the subject. She goes on to discuss her father’s work in regard to other screw propeller designs, such as by Smith, Bramah, Shorter, Trevithick, Cummerow, Woodcroft and Ericsson. While under the guise of defending the work of her father, Vansittart was displaying detailed comprehension of this particular engineering field and demonstrating an active ability to draw comparisons between the technicalities of these inventions.

The paper also provides insight into Vansittart’s role as a solo engineer and her work on the Lowe-Vansittart propeller of 1868. She writes:

I ask your attention to what I have personally done with the “Lowe-Vansittart” propeller. With this I conducted many experiments against the (so-called) “Griffiths,” “Mangin,” and “Hirsch’s” propeller previously to fitting it to those fine ships which I have had the honour of fitting it, and I have proved conclusively, to those who are well versed in the matter of screw propulsion, that the “Lowe-Vansittart” propeller gives increased speed with lessened consumption of fuel, whilst it minimises vibration, and confers the further great advantage of full backing power. Besides these desiderata, it effects a saving upon all things used in the locomotion of a screw ship, and by taking hold of the back water, it does away with slip and obviates all drag upon the shaft and wear and tear of machinery (Vansittart 1882, p 9).

In relaying what she has personally done, Vansittart is acknowledging her work as an independent engineer, not only as an adjunct to her dead father. She confirms that she herself has managed experiments in relation to existing propeller designs, listing the improvements she has made, and taking full ownership over her work, while also demonstrating her technical fluency. A similar example can be found in an edition of the Society of Engineers journal from 1876, where Vansittart appears in the discussion section on an article on ‘screw propellers, their shafts and fittings’. Discussing the Lowe-Vansittart propeller she is reported to have said that ‘she had superintended the fitting of all ships, and her screw had given full backing power with a less consumption of fuel than was usual, and had entirely done away with vibration’ (Nursey, 1876, p 175).

In the 1882 pamphlet, Vansittart does not only include her own words and image, but also those from other people. This includes many external sources designed to prove that her assertions about her propeller are correct, such as testimonies from engineers and ship captains, alongside tables of results for tests that had been run. One of the ‘official remarks’ states: ‘the small amount of vibration with the Lowe-Vansittart propeller is remarkable.’ Vansittart herself adds further comment to this: ‘I may remark that this is the first instance of a tumblerful of water being placed over a propeller when in full action, without a drop being spilt’ (Vansittart, 1882, p 10). Another official remark from the Admiralty is also included:

Madam, –The last trial of your screw on H.M.S. Druid was quite satisfactory, and no further trial is at all necessary, –I am, Madam, your obedient servant, VERNON LUSHINGTON. Admiralty, 4th Jan., 1870 (ibid, p 11).

As well as further letters, an article from The Times from 1869 and printed in the pamphlet testifies to the success of the Lowe-Vansittart propeller from respected sources. It writes that the trials of the propeller on the HMS Druid have shown ‘the superiority of the Lowe-Vansittart propeller over any other now in use’ (Anon, 1869c, p 10). The final page of the pamphlet details the awards won by the propeller, which include a first-class diploma at the Kensington Exhibition in 1871, a first-class diploma and medal at the Dublin Exhibition, 1872, a first-class diploma and silver medal at the Paris Exhibition, 1875, and later diplomas and medals from exhibitions in Belgium, Italy and Australia (Vansittart, 1882, p 35).

Beyond her achievements as an engineer, which are confirmed in the successes of the Lowe-Vansittart propeller, it is apparent that Vansittart was publicly known as the inventor of the propeller and as an advocate of her father’s work. As discussed earlier, Vansittart, in pursuit of recognition for her father, had no choice but to adopt a public facing role, but we might want to further interrogate how she was received as a woman in the field of engineering, especially given the previously discussed dominant cultural norms that women – in particular married women – should remain in the domestic sphere.

Vansittart’s position as the daughter of James Lowe does appear to have contributed to her acceptance as an expert in the field, perhaps helping to by-pass any concern about her gender and marital status. As already argued, her position as a devoted daughter and married woman, rather than as an woman engineer in employment (which may have been far more threatening), may have helped assuage any doubts about her position. Reporting on the forthcoming trials between the Lowe-Vansittart propeller and the Griffiths, an article in The Times spoke of a prevailing curiosity around the propeller due to Vansittart being Lowe’s daughter:

Considerable interest is manifested among naval men as to the result of the competition, it being well known that Mrs. Henrietta Vansittart is the daughter of the late Mr. Lowe, who was the original inventor of the screw, and who, so long ago as 1838, first introduced the then new principle of steam propulsion to the notice of the Admiralty (Anon, 1869b, p 5).

It continues to explore Vansittart’s reason for developing the propeller, framing her work in the same way that she herself chose to, as a dedication to her father:

Since her Father’s death Mrs. Vansittart has devoted herself to the task of working out the invention to a greater state of perfection, and she now seeks to obtain from the present naval authorities a due recognition of its merits, which she claims to be far higher than those of any screw yet adopted in the navy (ibid).

An earlier article from The Times in January 1869 shows further evidence of this way of framing her engineering practice:

In accordance with orders received from the Admiralty, an official trial of Lowe’s patent marine propeller, which has been further improved by his daughter Mrs. Vansittart, was made on Wednesday off the Maplin Sands […] The trial on Wednesday was undoubtedly successful, the ship being quite free of vibration. It was a bold course on the part of the adaptress to risk the reputation of the invention by attached the blades to a boss to which they had never been adapted before; but the result enabled Mrs. Vansittart to fit the Griffiths boss with the certainty of obtaining a very marked advance over all known screw propellers (Anon, 1869a, p 7).

After her status as the daughter of James Lowe is highlighted, the article goes on to praise Vansittart for her boldness in her adaptations, showing her work to be superior to previous versions. The feminised use of ‘adaptress’ is notable and could be intended to highlight the irregularity of her position as a woman in the field.[18] Contemporary reports in the press appear, therefore, to concur with Vansittart’s own assessment of the propeller’s benefits for ship propulsion. Her position as a woman is not directly addressed, nor is it called upon as exceptional.

Returning to the pamphlet, the inclusion that tests on the design were at the behest of the Admiralty is also worth drawing attention to, as it helps us to understand who supported Vansittart and the relationships she might have had as an inventor. A second letter from the Vernon Lushington is included in the pamphlet in which he feels that it is his duty to explain why the Admiralty is not using the propeller on more ships. Vansittart offers an explanation of how she has managed to gain the support from others, including the Admiralty, for her work, which is again framed around her being James Lowe’s daughter:

When [shipowners and managing engineers] become acquainted with the fact that I am the daughter of the first inventor of screw propulsion as in use, they gave me every encouragement. An eminent engineer said to me: “If you were not Mr. Lowe’s daughter, I should not advise my company to permit you to fit your propeller to one of our finest ships” and I am quite sure that, had the Lords of the Admiralty “not cared” as to who was the inventor of screw propulsion, I should not have gained the confidence and co-operation of so many distinguished gentlemen attached to that honourable Board (Vansittart, 1882, p 14).

The original point of this paragraph in her paper was to prove that the person behind an inventor is important, against claims that this was not the case, thus fitting her agenda to secure the legacy of her father and show why inventors of patents deserve recognition (and, as discussed below, money). However, it also illuminates a more subtle point about Vansittart’s place as a woman in the field of engineering and her experiences there. We might read between the lines and infer that, while her father’s previous role as inventor was a helpful access point into the field and a means to explain her presence to the wider (male) world, she herself knew that without her own evident engineering ability and the confirmed success of her propeller, she would not have gained the support that she evidently had.

The second letter from Lushington is revealing on a further point. Vansittart was arguably a successful engineer in her own right, as indicated above, but her ability as a businesswoman was less apparent. Like her father, she failed to make money from her invention and had to spend her own money financing its development, a point she makes clearly in her pamphlet. The letter from Lushington shows that she was trying to receive some form of remuneration for the use of her propeller, but that this is ultimately unsuccessful. She speaks of the difficulties for patent owners to be sufficiently remunerated, lamenting how inventions are often used without permission, which was what led her father to take legal action in the 1840s. Vansittart did not renew the patent for the Lowe-Vansittart propeller in 1882, due to the associated cost, which she estimates to be five or six hundred pounds. She writes: ‘Alas, poor inventive genius! You have my heartfelt sympathy’ (Vansittart, 1882, p 19). Though it is worth speculating on the idea that, had she made any money from the propeller, and been more of a successful businesswoman, she may have found her position as a married woman engineer harder to maintain and her rights to her earnings could have been challenged based on her limited legal status as a wife.[19]

An unsung legacy

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/006Henrietta Vansittart is an example of a woman who managed to forge a place for her engineering work in a male-dominated sphere. Without the advantage of formal education, she achieved recognition and success in her lifetime, all while being a married woman operating outside of her husband’s interests. It is worth asking, therefore, why more academic attention has not been paid to her work and life, especially given that she is an example of the non-domestic lives that women could have in the Victorian era, despite strong social norms and a lack of basic civil rights for women (especially married women). Why has there not been a stronger legacy written for her? For this we can consider the ways in which Vansittart moved beyond the demarcated ‘separate spheres’ of the domestic and the public, and how her habitation of both spheres challenged the dominant ideologies of the time about gender roles within these spheres. We can also consider who recovers a person’s legacy – forgetting is sometimes the act of not remembering to look.

Henrietta Vansittart had an unconventional working life, but she also had an unconventional private life. In considering her legacy, we cannot ignore the complexities of her life and that both her public and private lives can be viewed as transgressive.[20] While Vansittart lost her engineering mentor, her father, fairly early in her life, there was another older male figure who played an extensive role in her life – her lover, Edward Bulwer-Lytton. This was an affair that continued for over a decade, including while Vansittart was working on the Lowe-Vansittart propeller after her father’s death (the affair began in 1859; Vansittart’s father died in 1866; the new propeller design was patented by Vansittart in the United Kingdom in 1868; and the relationship with Bulwer-Lytton ended in 1871). According to her entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, the liaison was so well-known that the Prime Minister at the time, Benjamin Disraeli, commented on how the attachment was keeping Bulwer-Lytton away from his duties in the House of Commons (O’Mahoney, 2012). Vansittart did not only have a public persona as an engineer but also as a mistress of a well-known MP and author, who was known to have had an array of affairs. She lived separately from her husband for many years as a result of this, a living situation that would not have been viewed kindly in the mid-nineteenth century, even if it was not entirely uncommon (Gleadle, 2017, p 86). Yet there is, as yet, no uncovered evidence to suggest that this irregular set-up impeded her engineering work, perhaps indicating that these two ‘spheres’ of her life were able to co-exist without one impacting on the other.

Surviving letters from Vansittart to Bulwer-Lytton from the family archives point to Vansittart’s ‘romantic’ disposition, offering a counterpoint to her technical literacy demonstrated in the pamphlet. Here we see her role as lover, where she is passionate and dreamy, rather than writing as a devoted daughter or accomplished engineer. In fact, in her obituary in the Journal of the London Association of Foreman Engineers and Draughtsmen it is written that ‘there was much of the romantic in her nature and this […] raised her above the average status of ordinary womanhood’ (quoted in O’Mahoney, 1983, p 10). The flowery nature of their correspondence can be seen in this early letter from 1862:

Dearest Sir Edward,

I am very happy to hear you have found so pretty and pleasant a spot for your writer’s residence and I exceedingly rejoice that you have got rid of your pains. If any magic art of mine could have bereaved you of your pains, you should not have felt them twice, but I hope there has been magic in my prayers which I have offered up for you, and if these should be all your maladies will have passed down a precipice from whence there is no way for them to return […][21]

Some of her letters are illegible, either through intent, or because of the excitable manner in which she wrote them. The florid tone can be found throughout, with dramatic fights and subsequent reconciliations between the pair. Her insistence on writing a letter of condolence after his death to his family, despite it being badly received, shows the meaning he held for her in her life.[22] Though arguably it might also show a certain degree of obliviousness towards propriety and other people’s feelings. One might suggest that Vansittart’s dogmatic insistence on serving her father’s memory, alongside this kind of dramatic romantic behaviour, shows that Vansittart had a persistent, at times self-absorbed nature, that may have served her well in breaking down barriers to achieve her goals. Other than the one letter where she speaks to him of her father and his work (mentioned earlier), there is little to suggest that Bulwer-Lytton played a role in her engineering work, but we cannot know for certain one way or another. It seems fair to assume that neither her lover nor her husband actively prevented her from undertaking her engineering work. Bulwer-Lytton did support Vansittart financially. In the surviving letters from Vansittart to Bulwer-Lytton there is mention of the money that he gave to her. Their affair had apparently come to an end by the early 1870s, but they are still in correspondence, often about money. In 1871, two years before Bulwer-Lytton died (leaving her a sum of money) she wrote to him saying she wanted ‘her trust’ handed over to her husband, as she wanted the trust to cease.[23] Without corresponding sources, the exact nature of this trust is unclear, as well as why she would want that trust handed over to her husband, but we can assume from the letter that Bulwer-Lytton supplied her with a pecuniary fund and that this was something that her husband knew about. A few days later, she wrote to Bulwer-Lytton more extensively on this topic:

You are cruel to answer my letter as if its contents contained mercenary feelings; and you need not speak to me about my husband as I do not care a bit about him, neither do I care a jot about money. I did not estrange myself from you; you estranged yourself from me […][24]

In amongst questions of who ended the affair, the letters tell us that money played a role in their relationship, something that Vansittart professes not to care about, though her pamphlet shows that money was certainly a concern in relation to her work. The fact she received money from her lover is interesting given her insistence in her pamphlet that she never begged or borrowed a penny from anyone. We might wonder at her definition of this. It has already been established that Vansittart was not necessarily an accomplished businesswoman and was unable to make any financial gain from her propeller (though this may have been part of the reason she was able to operate as a woman in the field as she was not seen as ‘in employment’), so we might infer that the allowance he gave her was important to her being able to continue her engineering work. It is also interesting to speculate about the money that he left her in his will (he also left a smaller sum for her husband). Was there an agreement between the three of them about financial support provided by Bulwer-Lytton? Was the money offered to help Vansittart with her work on the screw propeller? Further evidence is needed to fill in the gaps.

Henrietta Vansittart’s rich and varied life ended in a sad and untimely way. She died in an asylum in Newcastle from anthrax and acute mania in 1883, after being found wandering the streets in a manic state. Her case notes reveal the nature of her illness and her suffering from it. They state that she was a danger to others and prone to violence, shouting loudly about ‘the devil, the Virgin and God’. On admittance, her body was marked with bruises and she spoke of personal interviews with ‘the Virgin’. Throughout her stay, the case notes indicate that she was often violent and excited, talking frequently on the same religious themes. Her death is listed as taking place on 8 February 1883: ‘during last night she gradually sank. Stimulants were given but she died this morning at 7.45, in the presence of nurse [first name illegible] Ross, of acute mania and anthrax.’[25] The painful effects of the anthrax, including weeping boils, are described in the case notes, and had worsened before she died, but there is little detail in the notes about how it began and its nature.[26] In her letters to Bulwer-Lytton, her persistent ill health was mentioned, though nothing relating to mental illness or anthrax. In a letter to him in 1870 she explains that her doctor recommended that she did not take a trip to the United States of America that she had been planning (this trip may have been to promote her patent in the United States, which is dated ‘May 4, 1869’). Thus, we might understand her early death as unavoidable and tragic, cutting short her engineering career and perhaps impacting on how she was remembered. Her husband died in 1902 but did not appear to have commemorated his wife.

While family legacy had been central to Vansittart’s work, she had no family to provide her own legacy, being without children. Indeed, as already highlighted, the pamphlet she wrote herself acts as her legacy, providing us with much of the information we have about her work. In addition – other than the London Association of Foremen Engineers and Draughtsman – there is little evidence that Vansittart moved in any other scientific or political circles. She was not, for example, part of the suffrage movement that was developing during her lifetime. Though this was not unusual for women in this era – there are many examples of women who did not support the movement – Vansittart does not follow the common pattern that women involved in engineering before 1914 often had a connection with the campaign.[27] The women’s suffrage movement played a pivotal role in the lives of Hertha Ayrton and Katharine Parsons, for example, who both embraced activism as a means to further the position of women. Parsons was a member of the Conservation Women’s Suffrage Movement and spoke publicly about her belief in greater opportunities for women, which led to her co-founding the Women’s Engineering Society (Heald, 2019). Ayrton marched on many militant suffrage marches between 1911 and 1913, building strong relationships with several women working toward suffragist aims (Bruton, 2018). In contrast, Vansittart did not appear to hold any strong beliefs about women’s rights in a general sense, only in regard to family legacy, though what she chose to say publicly might have differed from her private opinions. Her lack of association with the women’s movement could account for why her story has not been recovered, as this is an aspect of women’s history in the Victorian era that has generally received more attention.

Vansittart’s field – engineering – could also be a factor. It is only recently that academics have started to search more actively for the historic role that women have played in engineering (see Introduction). It is in an edition of The Woman Engineer in 1983 – one hundred years after her death – that we find an early example of someone trying to recover the life and work of ‘probably Britain’s first woman engineer’. The author B M E O’Mahoney (who also wrote Vansittart’s ODNB entry) muses on why she has been forgotten:

Probably the circumstances of her death […] caused Mrs. Henrietta Vansittart to fade from memory, except for a passing reference to her in the Dictionary of National Biography […] as the daughter of James Lowe (O’Mahoney, 1983, p 1).

It may also be that before O’Mahoney nobody had been looking for evidence of women’s participation in engineering in the nineteenth century, as it was assumed that there would be nothing to find. It is worth noting that Vansittart was not Britain’s first woman engineer; the work of engineer Sarah Guppy on bridges in the early nineteenth century shows that women’s contribution to the field extends further back. Guppy, like Vansittart, has also not received the research her work and life deserve and there are likely to be further examples of women that we are yet to discover.

Conclusion

https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/211505/006In recovering the life and work of Victorian naval engineer Henrietta Vansittart we find an example of how a woman was able to find a place in the field of engineering despite the limited opportunities for education and training. For Vansittart, her father’s engineering work was the means through which she received an education and motivation to develop her own engineering practice. As with other women who have historically contributed to engineering, such as Blanche Thornycroft, Rachel Parsons and Dorothée Pullinger, the role of family, in particular fathers, is crucial to how they accessed knowledge and practical skills. As research into women’s routes into engineering pre-1914 develops, it is becoming increasingly apparent that familial and spousal collaboration were key access points for women.

In the case of Vansittart, paternal influence takes on an even greater importance: after her father’s death, her engineering work became the way in which she carved his legacy and honoured his engineering work. However, it is through honouring her father that she became a successful engineer in her own right, with a public persona as inventor and screw propeller expert, and with champions amongst the Admiralty and other naval engineers. In her lifetime, she held patents for the Lowe-Vansittart propeller in several countries, won awards, and spoke publicly on the topic to scientific institutions, all of which were exceptional for a woman at the time. This article has also considered this in terms of Vansittart’s marital status and the mid-nineteenth century ideals about married women’s domestic status. While there is growing evidence to support the idea that married women were more active in the sphere of work than has been previously thought, there were particularly strong ideas about the need for married women to stay at home to preserve the family and her husband’s interests. It is interesting, therefore, to consider the strategies that Vansittart deployed to pursue her objectives, despite being married, including positioning herself as a devoted daughter serving her father’s memory, which aligned with feminine duties towards their kin. In doing so, however, she still managed to provide a record of her own work and legacy through her published pamphlet from 1882, where her own words are recorded. Indeed, recovering Vansittart’s voice and agency was one of the objectives of this article, to show the multifaceted, complex personas women had, despite the barriers placed upon expectations of what they were capable of. For this, uncovering the personal letters of Vansittart to her lover were crucial, as they provide another layer to our understanding of her character and modes of expression that go beyond her achievements as an engineer.

Given the unconventional nature of her life and work, and her public existence in her lifetime, we might expect to know more about Henrietta Vansittart. Through the forgetting of Vansittart, we learn something about the way women’s legacies are written (or not written). She wrote her own legacy through her pamphlet. But without children, or other interested relatives, there was no one to continue sharing it and so she slipped through the cracks. Thus, it is manifest that we should persist in looking for women’s place in engineering, and other fields; the evidence suggests that we only have to actively look and there will be much to find.

Acknowledgements:

The research that led to this paper was part of the project ‘Electrifying Women: Understanding the Long History of Women in Engineering’ (University of Leeds), funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). Special thanks to my project team, Liz Bruton and Graeme Gooday, for their help with my research into Henrietta Vansittart and their varied insights into the history of women in engineering.

Tags

Footnotes

https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co39465/model-of-the-lowe-vansittart-screw-propeller-blades-model-representation Back to text