Ten out of ten: a review of the last decade

Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15180/242202

Introduction

In honour of the Journal’s tenth birthday, we asked a collection of authors with huge and varied experience of the cultural sector to think about the last decade and pick one thing that stands out for them. The brief was open and included books, exhibitions, digital innovation and general trends. The only restriction was that the contributions were short and were accompanied by a single image.

Spectacular Bodies/The Return of Curiosity

Spectacular Bodies (curated by Martin Kemp and Marina Wallace), Hayward Gallery, London, 2000, linked to influential book: The Return of Curiosity, Nicholas Thomas, Reaktion Books, 2016

Reviewed by Ken Arnold, Director, Medical Museion and Professor at University of Copenhagen.

It was a dauntingly ambitious investigation of nothing less than the Art and Science of the Human Body from Leonardo to Now. Three hundred stunning exhibits illuminated the theme, from paintings and sculpture to instruments and models. The show reiterated how much aesthetic potency lurks in medical and scientific enquiries from history, and how much epistemological significance can be derived from body-oriented art. ‘No science without fancy and no art without fact’, as Vladimir Nabokov had it. We’re used to such broad fare now, but the discipline-busting suggestiveness of Spectacular Bodies was audacious, and to some it even seemed threatening.

Just over the exhibition threshold, audiences were arrested by Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Doctor Jan Deijman’, a full-frontal depiction (as if just for us) of a peeled scalp, brain dissection in progress. The cadaver was that of a hanged criminal, Flemish tailor Joris ‘Black Jan’ Fonteijn. Also drawn from science-into-art works were Franz Xavier Messerschmidt’s late eighteenth-century sculpted bronze heads, with their frozen grimaces. From historical medical education came models in wax and ivory, anatomically prepared skeletons, foetuses preserved in liquid, and a surgical kit, presented in a series of artful juxtapositions. For me, it was Joseph Towne’s 1829 wax model ‘Section of the Thorax at the Level of the Heart’, its thrown-back head revealing a gaping mouth and menacing eyes, that most singularly folded art and science in on each other. Drawing on techniques and materials prefigured by the show’s historical works, the exhibition’s contemporary exhibits reminded us that artists today still confront the profound significance of our corporeal substance. Key amongst them was John Isaacs’s accurately coloured and proportioned model of an untidily dismembered corpse. This shocking mess insisted that decaying flesh – still death rather than still life – belonged here too.

Hayward Gallery’s halls were filled with a kaleidoscope of human physicality: a parade of Spectacular Bodies indeed. Redolent of Gunther von Hagens’s controversial display of plastinated specimens, Body Worlds, Kemp and Wallace’s show similarly reasserted the power of our own physical form. But here, careful curation further invited us to contemplate equivalence and singularity, progression and disruption, hierarchy and accumulation.

The close of the last millennium witnessed a series of projects and exhibitions that entwined science with art. I oversaw a number as we built up momentum towards the launch of Wellcome Collection in 2007. But Spectacular Bodies was different. Arrayed across an expansive stage and energised by the brash confidence of ‘show business’, it showed that this subject matter and curatorial thrust could engage viewers beyond the knowledgeable or quirky few. It demonstrated how readily the new audiences for contemporary art who flocked to Tate Modern could also be engaged by science and medicine, especially through a lens of cultural significance. The influence of this ground-breaking exhibition rippled across the next quarter of a century, not least in some of the curatorial approaches that we adopted at Wellcome.

Spectacular Bodies offered much to gorp at and delight in, but it also encouraged us to lean in and do a bit of work for ourselves. Here was a visual essay on the potential rewards of flexing our curiosity, pursuing the inquisitive dissection of the human condition through art and science. In retrospect it seemed a perfect prefiguring of Nicholas Thomas’s proposal laid out fifteen years later in his book The Return of Curiosity: an invigorating and optimistic celebration of the enduring ability museums have to activate our ‘fertile and necessary’ senses. On the verge of an era when all of us found ourselves spending more and more time privately scrolling through images, texts and micro-movies, this gathering of objects and art in the shared space of a gallery, with its physical as well as visible potency (a ‘conjuncture of intimate actuality’ according to Thomas), was an important reminder of how exhibitions can uniquely ‘agitate [our] innate investigative spirit’.

(My review of Thomas’s The Return of Curiosity can be found at: https://journal.sciencemuseum.ac.uk/article/return-of-curiosity/#keywords)

Beyond the Lab

Beyond the Lab: The DIY Science Revolution, Science Museum and various other venues, 2016

Reviewed by Andrea Bandelli, international consultant and advisor in the field of science communication.

Beyond the Lab: The DIY Science Revolution[1] was a tribute to inclusivity in science, and to how scientific knowledge is created and shared. Developed and launched at the Science Museum in London in 2016, the exhibition then travelled across Europe to over thirty museums, cultural centres and public spaces. Over the course of three years, it reached millions of people, inspiring them with the message that science is not just the domain of professionals in labs – it belongs to everyone.

The exhibition was a timely exploration of emerging scientific trends like citizen science, participatory research, and the integration of art and science. But in hindsight, it was also a forward-looking project that captured issues that have since become mainstream in both science and society. Long before consumer devices like smartwatches, AirPods and fitness trackers became ubiquitous health technologies, the exhibition featured stories of citizen scientists who hacked medical devices to address their own health concerns. More than an exhibition, Beyond the Lab was a collaborative effort that trusted citizens to take ownership of science.

The exhibition showcased how people outside of formal scientific institutions were contributing to research, often tackling local problems that larger organisations overlooked. From environmental monitoring to medical device innovation, the exhibition featured stories of non-experts who empowered themselves to drive science forward. At the time these stories were groundbreaking, but today citizen science is everywhere, from environmental activism to global projects involving millions of volunteers. The exhibition can be seen as a crucial early advocate of this democratisation of science, a movement that continues to grow, engaging people from all walks of life.

The exhibition also played a key role in exploring the intersection of art and science, featuring visionary creators like Lucy McRae, Jakob and Lea Illera, and Anouk Wipprecht. They contributed projects that blurred the lines between scientific innovation and artistic expression. McRae, known as a ‘body architect’, explored futuristic technologies that reshape the human body, combining elements of design, technology and biology. Wipprecht’s work with wearable technology incorporated robotics and fashion, creating interactive clothing that responds to human behaviour. Their works proved that creativity and innovation are born at the intersection of disciplines, where new ideas thrive.

A truly European effort, Beyond the Lab was part of a large project involving over thirty institutions from different countries, embodying the spirit of RRI – Responsible Research and Innovation (a short-lived but quite influential concept that shaped European science policy in the 2010s). Although coordinating such a wide-ranging collaboration may not have been the most efficient process, it was highly impactful. The institutions involved learned from one another, creating a rich, collaborative atmosphere that extended beyond the exhibition itself. This co-development approach mirrored the participatory science it celebrated, showing how scientific progress is often the result of collective effort.

The collaboration didn’t stop at the exhibition – it also produced toolkits and manuals to help other institutions engage the public with contemporary science. These resources encouraged critical thinking and active participation, ensuring that its impact would last far beyond the lifespan of the exhibition.

In short, Beyond the Lab not only anticipated key themes that are now mainstream in science communication, but it also redefined how we think about who can participate in science. By showcasing the power of everyday individuals to shape scientific discovery, the exhibition remains a powerful example of how science is for everyone, and of everyone.

Wellcome Collection ‘Stories’ webpages

Rachel Ellis is a Director at Thirty8 Digital, and a digital reviewer for the Museums Associations journal. Here she writes about how the Wellcome Collection set the bar high in a new digital era.

In my many years of working in the digital realm of museums I can (crudely) split the last three decades into three digital eras. First came the ‘bums on seats era’, when we primarily used museum websites to point people in the direction of the front door or ticket desk. It was the late 1990s, and the dot com boom was happening elsewhere; sites such as Amazon and LastMinute.com were in the headlines with their stratospheric rise and then fall (and now rise again). As the new millennium began, and the bubble burst, there was caution in the wider world around investment in digital, which was probably reflected in a cautious approach to web development in museums too. Museum websites in the late 1990s and early 2000s were, in the main, an online version of printed leaflets and brochures, and the web team (usually consisting of one, maybe two people) were firmly rooted in museum marketing departments.

Then came a particularly busy and much longer second era, which we’ll call the skeuomorphic era.[2] For the first decade of the millennium, web teams grew, and museum websites became more than just an online copy of their institutions’ marketing material. Virtual museums, largely based on what could be found in the physical museum, were born. As technology developed museum websites became more like the actual institutions they represented, giving web visitors access to digitised collections, digital exhibition spaces, and opportunities to interact with things like online games, such as the Science Museum’s Launchball.[3]

Emerging technology enabled museum websites to become much more browsable and engaging. Examples include the National Museum of Science and Industry’s (now the Science Museum Group’s) Ingenious project, launched in 2003 and displaying over 30,000 images from across the Group’s collections. Interfaces moved on from simple search boxes, which worked well for audiences who knew what they were looking for, but less well for those who didn’t. Projects, like Ingenious, focused on curated content, giving users a more exhibition style experience on the web, inviting exploration and not just the facility to search the collection.[4]

The era of Skeuomorphism is still, for many museums and institutions, alive and well, and will probably never fully disappear, but in the last decade things have started morphing into something different and museums are slowly pushing at the door of a new digital era. The name of this new era is still up for debate, but I’m certain it should involve the word stories. Telling stories is really at the heart of every museum, and in this new era it doesn’t matter whether people hear these stories while scrolling through the web or strolling through a gallery. The digital realm of many museums now has equal importance to the museum’s physical realm and web content isn’t simply a way of encouraging real-world visitors. The reach of our stories has finally become key.

In 2018 the Wellcome Collection became trailblazers for this new storytelling era by not simply regurgitating stories told in their Euston Road exhibition spaces or creating virtual walkthroughs of those physical spaces. A philosophical shift in how they saw their website was key – their digital presence took on its own role as a medium for expression about the collection; the website and social channels were Wellcome Collection rather than being a promotional tool for the Collection.

For me the Wellcome Collection site broke the mould. By focusing the website’s aim to coincide with those of the organisation (in the case of the Wellcome Collection, ‘to inspire and encourage people to thinking about health, life and our place in the world’) they developed a site that could deliver this mission in original and meaningful ways, and to new and otherwise difficult-to-reach audiences. The Wellcome Collection stories[5] initiative (still going strong six years later) is built by both commissioning stories and inviting pitches. This ensures a wider range of perspectives – an organisational goal of the Collection – and a widening of representation too. The site uses a journalistic approach to its storytelling[6] with six well known content formats – serials, essays, interviews, photo galleries, book extracts and comics – working to a regular, proactive (not reactive) publishing schedule, which means there is always something new to read.

If developing our reach and encouraging engagement is a defining part of this new digital era, then choosing to showcase more voices and more perspectives is a sure fire way of achieving this – telling our stories in different ways to more people is a thrilling era to be part of and it’s great to see other museums, like the London Museum, recently take this approach to their digital strategy.[7]

Tsunami, September

Halima Cassell, Tsunami, September, McManus Museum and Gallery, Dundee, 2004

Reviewed by Jane Henderson, Professor of Conservation at Cardiff University.

Over the last ten years I have been moved, stimulated, challenged and excited by many museum exhibitions. Two that come immediately to mind were the Reframing Picton exhibition at Amgueddfa Cymru National Museum Cardiff[8] and Panorama Amsterdam at Amsterdam Museum.[9] Reframing Picton offers a welcome response to collections of empire, in this case focused on a portrait of Thomas Picton, described both as a war hero and as a tyrant slaver. The Museum commissioned a new and inspirational work by Gesiye, ‘The wound is a portal’ (which I found transfixing), and displayed the Picton portrait within a crate. Panorama Amsterdam is a city museum where the gallery space connects historical collections to contemporary analysis. This connection is delivered by an outer route hung in a moderately traditional style (although interspersed with art that responds to colonial trade) and an internal ‘lab’ space with different design, lighting and other subtle features that help you consider the more traditional art in context. Like the exhibition at Amgueddfa Cymru, this space includes many conversations and discussions. I found both to be exciting approaches to recognising untold stories without rejecting tangible evidence.

Even as I wrote this summary there was another exhibition that had my heart. It was a single ceramic piece, one of several pieces of contemporary art from the permanent collection in the long gallery of the McManus Museum and Gallery in Dundee. The sculpture was by Halima Cassell,[10] not an artist I had heard of before but whose work I find transfixingly beautiful. Perhaps it is because I am a conservator; I stopped to look at this single item for as long as the rest of my group was prepared to indulge me. I enjoyed the form, the texture and the shadows that it created; I wanted to touch it; I wanted to own it or another sculpture by Cassell. I wanted to be lost in the moment.

Why pick this single item in the permanent exhibition? Museums are special to me because they create moments of connection. They give us a chance to come in off the street and stumble across something that gives us a pause to reflect on beauty and our place in the world. It is surely this magic that sits at the very core of what museums offer. I had a moment in time, a connection between myself and another place through an object. That is why I have picked a single item from a permanent collection, an event with no press releases nor culture wars, which connected me to an artist who draws on Islamic influences and motifs from North Africa and brings architectural influences to ceramics. Connections across space, across cultures and experiences – surely it is these connections that give us all the opportunity to grow in our confidence and sense of place.

Camera Geologica / Mining Photography

Siobhan Angus, Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography (Duke University Press, 2024) / Mining Photography (CO Berlin, 2022)

Reviewed by Michelle Henning, Chair in Photography and Media at the University of Liverpool.

Siobhan Angus’s Camera Geologica: An Elemental History of Photography is part of a shift in studies of photography towards a new kind of concern with materiality. The materiality and objecthood of photographs themselves have been well-studied, but Angus is one of a growing number of writers, artists and curators turning their attention to the mineral and chemical constituents of industrialised photography. The concept of extraction brings together a concern with these constituents with a focus on labour and the economic and social relations of capitalism.

Angus’s book takes the form of a series of case studies centred on particular minerals — bitumen, silver, platinum, iron, uranium and rare earth elements such as europium, yttrium, cerium, terbium and lithium. It covers ground familiar in existing photographic history and theory but introduces new perspectives: she considers Niépce’s use of bitumen in his early héliographie, but also the less well-known study by James Waterhouse of the uses of bitumen in photomechanical printing, as well as the links between bitumen and the wider oil economy. She looks not only at the circulation of photographs in relation to the circulation of silver (as currency and commodity) but also the silver mines in the Americas and their dependence on forced labour. This interest in extraction reaches beyond photography, with precedents in (for instance) John Durham Peters’s work on ‘elemental media’, in the media-archaeological work of Jussi Parikka, and in studies of the dependence of the mobile phone industry on conflict minerals (Peters 2020, Parikka 2015).

This approach is especially relevant for museums, in my view, because it opens up new ways of looking at collections and exhibitions. Moving away from strictly art-historical, social-historical or history of science approaches, this kind of photographic history brings together a much wider range of disciplines and concepts. It links mineralogy and environmental science with social history and joins discussions of aesthetics and affect with theories of pollution and colonialism. Critiques of capitalism, anti-colonialist and environmentalist arguments are understood not as separate political concerns which provide different ‘perspectives’ but as a coherent framework for bringing the significance of material, and material practices, to light.

There are many artists exploring similar themes in their work, some of whom Angus discusses. Some also appear in the exhibition and accompanying catalogue Mining Photography, curated/edited by Boaz Levin and Esther Ruelfs at C|O Berlin (Levin and Ruelfs). That these approaches are becoming more widespread is indicated by the proliferation of exhibitions: for example, a recent show at the Open Eye gallery in Liverpool including Melanie King’s project Precious Metals, featuring daguerreotypes and palladium-platinum prints of supernovae (photographed by NASA), and silver jewellery made from used fixative.[11] At the Saatchi Gallery earlier in 2024, the exhibition METAMORPHOSIS: Innovation in Eco-Photography and Film featured works from the artist-led research project The Sustainable Darkroom and other artists including Scott Hunter, whose installation work ‘Darkroom Ecology’ used plants such as mint to absorb the silver produced in photographic processes, which would normally enter the soil and river beds.[12] In both King and Hunter’s work, photography expands beyond the image, and together with books like Camera Geologica, I am hopeful that this might stimulate a new elemental and ecological approach to exhibiting existing collections.

‘Dial the Switchboard’

‘Dial the Switchboard’ interactive telephone, We Are Queer Britain

Reviewed by Rebecca Mellor, Assistant Curator of Exhibitions and Chair of the Science Museum Group’s Gender and Sexuality Network.

When you pick up this phone and dial a number you hear a voice. A voice of someone who is struggling, afraid, lonely and desperately reaching out for reliable information in a wave of anxiety-fuelled misinformation. For many LGBTQIA+ people living through the late twentieth century in the UK, this experience was real.[13] This was a community built from a desperate search for help through trauma, sadness and loss, but also through hope for human connection and empowerment through knowledge.

At Queer Britain’s We Are Queer Britain exhibition, these myriad emotions and narratives are shared via an unassuming object.[14] Amongst the joyous rainbows and rebellious expressions of identity stands a cream-coloured rotary phone on a plinth. The phone’s tactility begs visitors to touch it, to physically lift the receiver and listen to the LGTBQIA+ history held within. This is the story of London’s helpline Switchboard as told by the volunteers who answered the phones and by the words of the callers (voiced by actors) captured in extensive volunteer notes.[15]

The relationship between the LGBTQIA+ community and museums has always been complex. Museums have excluded queer perspectives in the telling of histories through material culture. Where queer stories are shared, they have historically been centred in narratives of violence and tragedy, and focused on the medicalisation of the LGBTQIA+ community and disease.

The last ten years have seen remarkable strides, moving towards celebrating the LGBTQIA+ community in creative ways. Representation and diversity have moved beyond simply telling the stories of a community filtered through a ‘museum voice’, towards a true inclusivity where members of marginalised groups share their experiences in their own words – quite literally in the case of the ‘Switchboard’ phone. Queer tours of museums are available across the UK, explicitly queer exhibitions and collecting projects are increasingly common and are measurably popular with visitors.[16] In 2022, this approach found a physical home when Queer Britain opened its doors, becoming the first LGBTQIA+ museum in the UK. There is also growing support and community building for staff within the museum sector. The Queer Heritage and Collections Network supports the promotion of LGBTQIA+ history and culture across the sector, and at the Science Museum Group the Gender and Sexuality Network has been working to champion and support the queer community in our museums since 2022.

In general, science and technology museums have been slower to adapt to new approaches in queering their collections and displays though there is significant work happening now.[17] Rectifying the erasure and misrepresentation of the LGBTQIA+ community is not simply a matter of displaying more explicitly queer material culture; progress is about challenging deeply held heteronormative assumptions we make about our objects, our staff and our visitors. As someone who works in a science and technology museum, I was deeply moved by this beautiful display of recognition for how technology has enabled moments of LGBTQIA+ history and community building. Here Queer Britain illustrates how a telephone becomes an object of great social significance to an often-overlooked group by exploring it through a queer lens.

Museums are places of emotion – where we come into direct contact with the exceptional, innovative and beautiful – but also places where significance can be found in the very ordinary, exploring stories through objects that build empathy and connectivity in our lives while celebrating our diversity and unique perspectives. Queer Britain’s ‘Switchboard’ interactive does just this, illustrating the promise of the future in celebrating the LGBTQIA+ community while emotively reflecting our shared history.

Learning and Everyday Life

Learning and Everyday Life: Access, Participation, and Changing Practice by Jean Lave (2019)

Reviewed by Theano Moussouri, Professor of Museum Studies, UCL Institute of Archaeology.

The renowned social anthropologist Jean Lave’s long-established research into learning in practice stands out to me as one of the most influential and inspiring pieces of work in the last decade. In her recent book, entitled Learning and Everyday Life: Access, Participation, and Changing Practice, Lave (2019) weaves together ethnographic research and critical theoretical perspectives to shed new light on learning as everyday practice.

Best known for her conceptualisation of learning as situated in context (e.g. Lave, 1988; Lave and Wenger, 1991); Lave’s (2019, 1) recent book project) – set up in collaboration with anthropologist Ana Gomes of the Federal University of Minas Gerais – ‘attempts to work out a dialectical notion of learning as “changing participants’ changing participation in (humdrum, complicated, conflictual) everyday practice”’. This book, like Lave’s previous work, presents robust empirical research grounded in critical theoretical insights. By examining learning practices across different communities and settings, she has been able to focus on different modes of access to, and engagement with, these practices. As a result, she is able to produce more compelling conclusions and build a more complex picture of the diversity of ways learning can proceed. This is one of the key reasons why her work can be of particular relevance to museums and how they make learning possible for different communities through understanding and supporting different, more culturally responsive modes of access to it.

The increased emphasis on access, diversity and inclusion and the need to address inequalities in the way people, especially those from nondominant communities, engage with museums demands a better understanding of everyday social practice and the resources people create and draw on in the course of their everyday life. As Lave’s (1988) earlier work demonstrated, using traditional epistemological frameworks and concepts bears the risk of conscious or unconscious ‘deficit thinking’. In her 2019 book, she also highlights the role of social practice theory in helping us ‘analyse learning in/as practice in quite different historical periods and educational practices’ (Lave, 2019, p 83). The power of Lave’s analytical framework has had a huge impact on my most recent work, examining museum participation and meaning making in the realm of everyday family practices (Moussouri, 2024). In particular, it has helped analyse how family practices are enacted across settings (e.g. home, school, local park and neighbourhood, museum), how the arena of the museum can facilitate certain family practices and impede others and the elements of the family practices (doing family, displaying family and family paideia) that museums can draw on when working with families from nondominant communities. Despite the obvious implications and applications of Lave’s work in museums, it has not been employed as much as it deserves. Both her theoretical and methodological approach can present museum researchers and practitioners with knowledge, case studies and tools from which to reference their own work and practice when working with different audiences and communities.

Václav Jirásek: Infection

Václav Jirásek: Infection (London: Eastern Front), 2021

Reviewed by Michal Nanoru, a London-based Czech writer, editor and curator operating on the intersections of art, visual cultures and cultural criticism.

It’s 2014.

Obama is president and Taylor Swift is a country singer. Democracy is the default setting. Most Europeans haven’t heard of the refugee crisis. They don’t know what Charlie Hebdo is, or Bataclan, or Brexit, or Pokémon Go, or ‘X’, or even privacy settings on Facebook. The future looks optimistic.

Yet, instead of history ending peacefully, in the last decade it has shot off in all directions, individually for each of us – climate change; economic crisis; inequality; mass migration; cultural, info, trade, hybrid, and conventional wars; mental health crisis; opioid crisis; populism; inflation; ChatGPT – just not toward any inevitable progress. The vision of a liberal utopia has imploded. If you’re not in debt, you’re at least worried about your dignity, your status or your identity. The international structures that kept nation-states stable for the last seventy years have shaken at their foundations.

Even though that feels like plenty to define a decade, one piece is missing. Against this already precarious backdrop, a pandemic exploded with unparalleled abruptness and global reach and widened social and cultural divides even further.

The photos in Infection started to be shot in 2001 as a dialogue between Czech artist-photographer Václav Jirásek[18] and record label owner Dan Trávníček. For one therapy, for the other an aesthetic-critical expression, these meetings in the Moravian landscape in a wedding suit with plastic-bagged feet and a facemask spanned three years. The images used the then remote SARS-CoV-1 epidemic to visualise the individual’s separation from their environment, but the absurdity of reaction to the abstract global threat with a sandwich bag also evoked memories of the state-sponsored paranoia of the Cold War and the environmental urgency of the 1980s. Only years later has it become clear that Infection foreshadowed many features of the present – excessive consumption and contamination from plastics, pesticides and other pollutants; the proliferation of mental illness and various lifestyle diseases; the dearth of spirituality; and finally, the absence of solidarity and the collective unpreparedness of humans, lost both as individuals and as a species, to face global problems. In a post-apocalyptic setting that is as extremely aesthetic as it is obviously toxic, Infection’s sole human protagonist emerges as a naked laboratory animal, constantly at the disposal of some suspected higher power, a climatic or AI whim, or a simple human death.

After spending years in a private archive, in 2022, when published as a book,[19] Infection was to be presented along with a centenary celebration of the work of the fellow Czech Miroslav Holub as part of Science Museum Lates: Vaccines. Holub, a unicorn of a poet-scientist, won world recognition with almost two dozen books of poems about oxidation or protoplasm (not to mention the B-glucuronidase) as well as writing more than 150 scientific papers and developing a strain of hairless mice for experiments. He cherished the Enlightenment’s overthrowing of the old symbolic order by way of reason and used both poetry and science as instruments for debunking myths. In his view science was the only defence mechanism against the darkness of chaos and raging irrational fears. Yes, it was human, unpredictable and often failed, but he still believed it was the only trustworthy approach as it was the only method that could correct its own inconsistencies. Even if Holub understood that scientific, enlightenment reasoning was bound by time, he believed that in principle it made for the best and therefore the only option. Had he lived, he might have argued that while some might believe science got us into Covid, it certainly got us out of it.

In fact, Covid had already entered Holub’s nightmare – a post-truth era where, in the span of about ten years since the rise of unmoderated social media, the authority of traditional, until-now unquestionable institutions (including science) has been radically undermined. What the pandemic has ultimately laid bare – and what Infection shows so vividly – is that, over the last decade, not just individuals and generations, but entire projects of civilisation are finding themselves at a breaking point, revealing that economic growth and modern ideals of freedom and progress are closely intertwined and are not infinite. One can hope that what we are watching now is indeed civilisation in the midst of a mid-life crisis and not humanity in its final throes. Infection interprets PPE – ostentatiously standing between a disoriented individual and a natural world with which they will never again become one – and the reaction to the disease itself, as a transformative, restorative process: vital preparation for the next phase of evolution at a time when we are all anxiously awaiting the new shape our world will take.

Museums and AI – learning from artists

Hannah Redler-Hawes, Independent Curator, Museums Consultant and Open Data Institute (ODI) Associate: Director and Curator of Data as Culture, looks to the future of AI and museums.

In 2024 museums researchers are looking at how museums might respond to the rise of Artificial Intelligence.[21] They are asking what we mean by responsible AI in practice[22] and raising questions on how to address structural inequalities and biases in collections and data, including considering how we might design machine learning tools to critically analyse and enrich these data.[23]

As we grapple with whether AI heralds an epistemological break, systemic restructure, ethical minefield or an administrative headache, an important future-focus is to recognise the role museums can play in pinpointing potential and unravelling AI harms through public discourse.

For me as an art curator specialising in new and emerging media, the past decade has seen a dramatic increase in artists interrogating the social, cultural and ecological implications of burgeoning AI industries. At this critical point where museums need to consider closely their AI practices and policies, much can be learned from artists. Artists prompt us to look beyond individual applications at the wider cultural and ecological implications of AI. They provoke an exploration of human needs and humane value systems beyond the Big Tech agendas which museums often need to collaborate with.

For example, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler visualise the complex networks and resources required throughout the lifespan and disposal of an AI product; Harold Cohen, Mr Gee, and Licia He consider how we adapt to creative collaboration with machines, while artists like Anna Ridler,[24] Clare Strand[25]and Holly Herndon & Matt Dryhurst[26] turn the production of training data into art (Crawford, Joler; Cohen; Gee; He). Others challenge the presumption that inclusive data is the answer to algorithmic fairness[27] or argue for the protection of intellectual property[28] and public trust[29] – which, significantly, museums might do well to recognise as amongst their most valuable assets.

Artists also champion the protection of the role of human oversight and responsible data stewardship.[30] Alan Warburton’s AI-generated film The Wizard of AI[31] introduces us to his concept of the ‘wonder-panic’ condition. In this we toggle between awe at AIs abilities and concern at the exploitation, erasure and potential redundancy of creative practices. Warburton critically explores the doom-loops of inbuilt bias and the complexities of an AI-hallucinatory future based on data scraped from ‘old’ ideas.

‘Machination’ by Tessa Elliott and Jonathan Jones-Morris intentionally reveals its workings.[32] Completed years earlier, in 2000, it runs on a self-learning neural network written by the artists and based on a hand-crafted database of 1,000 household objects. Visitors’ faces are considered in a process which offers a visualised mapping of the work’s limitations and biases before it re-presents them to themselves as the object it thinks they most resemble.

The present-day problematics these works anticipate, such as the differences between machine and human vision, the difficulty in perceiving the ‘join’ between human, machine originality and meaning and the need to recognise that the limitations embedded in any database will shape what outputs it is capable of, will surely chime with museum professionals considering the future of collections-related experiments in AI tagging and interpretation, both authorised[33] and unauthorised.[34]

Taking into account the wildly different types and scales of museums operating in diverse cultural and geopolitical contexts, when it comes to embracing AI there will be no one-size-fits-all. AI might expand the purpose and function of the museum, it might automate thankless jobs, repeat mistakes or create new relationships with visitors. There will certainly be failures and dead ends. But once we recognise that AI is ‘not only the…technologies…but also the broader system of people, data, and processes’ (Newman-Griffis, 2024) artists and other researchers’ questions and explorations can offer transformational potential for any museum that wants to be critically engaged, self-aware and ethical, and that is unafraid to experiment with care for all involved.

The Stuff of Spectatorship: Material Cultures of Film and Television

The Stuff of Spectatorship, Caetlin Benson-Allot, 2021

Reviewed by Tim Snelson, Associate Professor in media history in the School of Art, Media and American Studies at the University of East Anglia.

Caetlin Benson-Allott’s 2021 book The Stuff of Spectatorship has helped reorient film and media studies away from screens and towards the study of seemingly peripheral objects. In these fields, ‘little attention has been paid to the material culture around viewers and their screens’ and how these influence meaning, not just the meaning of media content, but ‘the very concepts of film and television’ (Benson-Allott, p 1). Stuff focuses on a mishmash of artefacts that have shaped and influenced spectatorship across a range of viewing contexts. These include TV Guides, video and DVD packaging, alcohol consumed in cinemas, and cannabis smoked whilst binge-watching boxsets at home. Individually and cumulatively, these case studies tell a messier and more ‘complicated story’ about media culture (p 13).

Her historiographic approach is important because it begins not with media texts, but with where and how people encountered them – aligning with New Cinema History – but then allows us to turn attention back towards films and TV shows and why they mean. Rather than sidelining media content, Benson-Allott’s approach allows scholars to revisit and re-politicise textual analysis, ‘a long-esteemed methodology of film and media studies that has fallen out of favour’ (p 249). Her entangled stories of consumption of objects and films together reveal much about the classed, racial and gender politics underlying historical perceptions and oppressions of people, places and products.

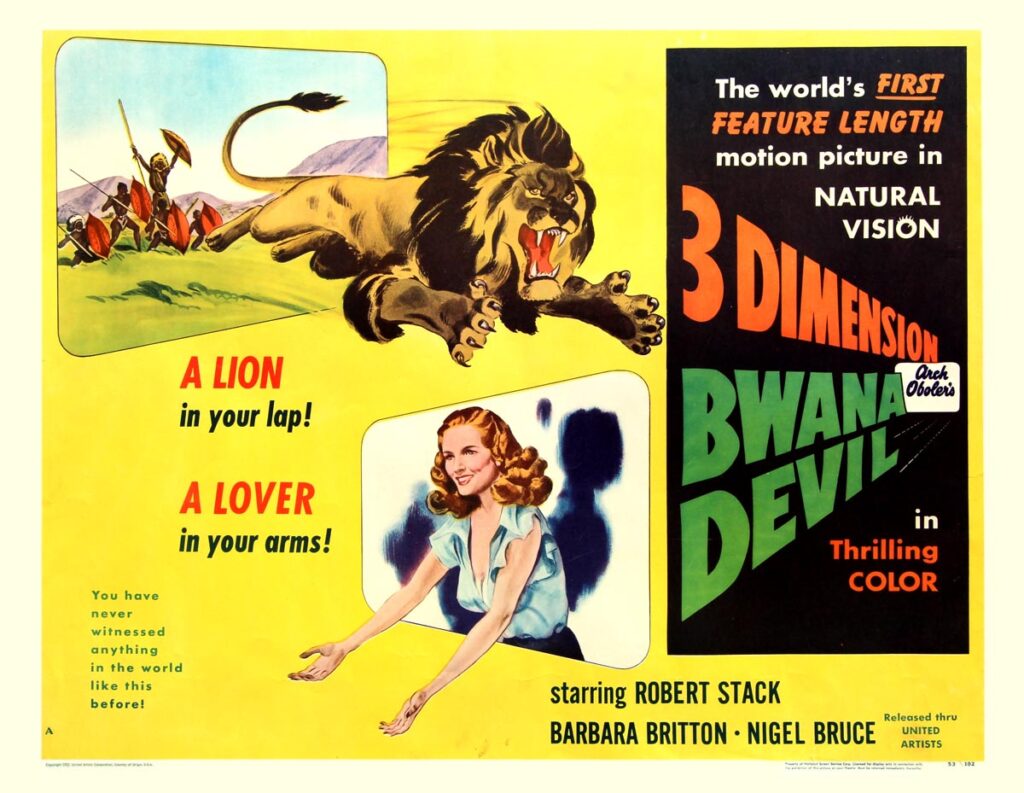

Stuff was vital to my recent project with the Science Museum Group,[35] which used film to investigate the interactions of media and medical objects. But Stuff speaks more generally to the value of these collections. The National Science and Media Museum (NSMM) has a range of technologies and objects used in widescreen and 3D exhibition, including a collection of 3D glasses used for specific films such as Bwana Devil (1952) and The Mask (1961). These give insight into how audiences were encouraged to experience these films, with, for example, Bwana Devil’s (over)promise ‘The Miracle of the Age!!! A LION in your lap! A LOVER in your arms!’ (see, for example, 3D glasses for ‘Bwana Devil’ | Science Museum Group Collection and Magic Mystic Glasses | Science Museum Group Collection).

However, the NSMM has also acquired more ‘mundane’ objects such as the envelopes for subscribers of the LoveFilm DVD-by-mail service to send back discs (LoveFilm return envelopes | Science Museum Group Collection). As an object, the return envelopes seem inconsequential, but they shaped millions of people’s experiences of films, television and video games across the 2000s and 2010s, as the media industry transitioned from high street chains, like Blockbuster, to streaming models of distribution.

These envelopes were a key part of people’s weekly routines, timing returns to improve chances of receiving a latest release or a specific film for a date night. As the tick box to report faulty items suggest, these envelopes could represent frustration and disappointment as much as joy. The compiling of your LoveFilm list of preferred titles (online and later in the ‘New LoveFilm App’) far from guaranteed receiving what you wanted when you wanted it. Also, because each envelope contained just one disk, your boxset binging was often disrupted by a lengthy wait for the postman.

A dramatic drop in demand for DVD-by-post and the rise of Netflix (initially created as competitor to LoveFilm’s dominance), encouraged Amazon, who now owned LoveFilm, to stop the service and switch to the new Prime Video streaming platform in 2017. Whilst these envelopes are now largely forgotten (hopefully recycled), they show how ‘material culture changes how people relate to film and television’ (p 19) at different moments in history and at different stages of life.